We need money. We need hits. Hits bring money, money bring power, power bring fame, fame change the game.

Young Thug

I

There is a persistent belief that it is much easier to be famous today than it used to be in the past.

This is about as lopsided as a result I’ve ever seen in a poll. It’s like asking if water’s wet. But to me the question isn’t nearly so obvious. The obvious answer would have been that its goddamn hard. As anyone who’s mucked around with Twitter knows, building an audience is a bloody hard game at best. Monetising such an audience is even harder.

All of which makes it seem that the creator economy is not for the faint hearted. So I decided to take a look at the major contenders.

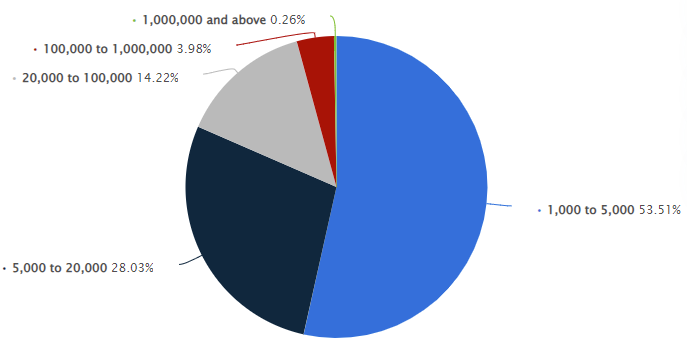

Let’s look at Tiktok fame. In order to have any meaningful level of impact you need to have at least 1m followers, which turns out to be 0.26% of the users. The numbers are from Statista, but they do seem to stand up to at least basic scrutiny.

What about Instagram?

It seems similar here too. 1.21% of users have over 100k followers on Instagram. A tier below, to have at least 50k followers still adds only 0.94% of users. This is a narrow slice!

What about Twitter?

Twitter is harder to find numbers for (was for me anyway) maybe because its not exactly the world’s best ad platform, which also means less folks actually care to figure it out. That said, 98% of Twitter users have less than 400 followers, which means the power law is bloody steep here as well.

What about YouTube?

Youtube seems a tad more democratised, with 500k accoutns globally having 100k subscribers or more. At least from an anecdotal Quora answer someone with 100k subs can aim to earn around $350-750 per month if from India, and around 4x that if from the US. Not exactly a celebrity, but not bad.

Breaking into the top 3 percent of most-viewed channels could bring in advertising revenue of about $16,800 a year, Bärtl said. That’s a bit more than the U.S. federal poverty line of $12,140 for a single person.

What about Spotify?

According to the most recent statistics from Spotify, over 7,500 artists are making $100,000 per year with Spotify streams, a number that’s grown by 79 percent over the past four years

That’s 7500 out of 8 million, which means we’d have to fight the decimal point gods to get anywhere.

I know that there are other platforms out there, but at least from the larger creator economy outlets out there, it doesn’t seem all that easy to make a living “doing what you love”.

II

So things are pretty hard today, at least if your aim is to become the next Dickens or the YouTube version of George Clooney. After all if its easier to get famous today, as seemingly everyone believes, it should be easier right?

To start with then, how hard was it exactly to become a Hollywood heart-throb back in the day?

By one accounting, about 0.04% of the English speaking population is famous as an actor, since there are about 1.5 billion English speakers and there’s around 600k people who have Facebook entries as Actor. I’m partial to this because it was a Fermi estimate done by my friend Sam Arbesman, but at the least this seems to put an upper bound. After all, its not like everyone even wants to be an actor and fails.

There’s another article that argues only around 2% of actors earn a living as an actor, which I think seems like an extremely low bar to clear.

Another way to estimate is that there’s around 160k actors that SAG-AFTRA represents. And to get into it you need a job given by a director, and must have worked at least 1 day in a speaking role or 3 days in a background role. So if you were extra zombie #3 in a Rodriguez movie for 3 days, you can probably get in (a high bar). Around 2% are what you’d consider celebrities (will recognise them at starbucks, maybe). 20% make over $100k a year, which seems respectable as a job goes. Not quite Clooney though.

Ok so that’s Hollywood. What about, say, becoming a novelist?

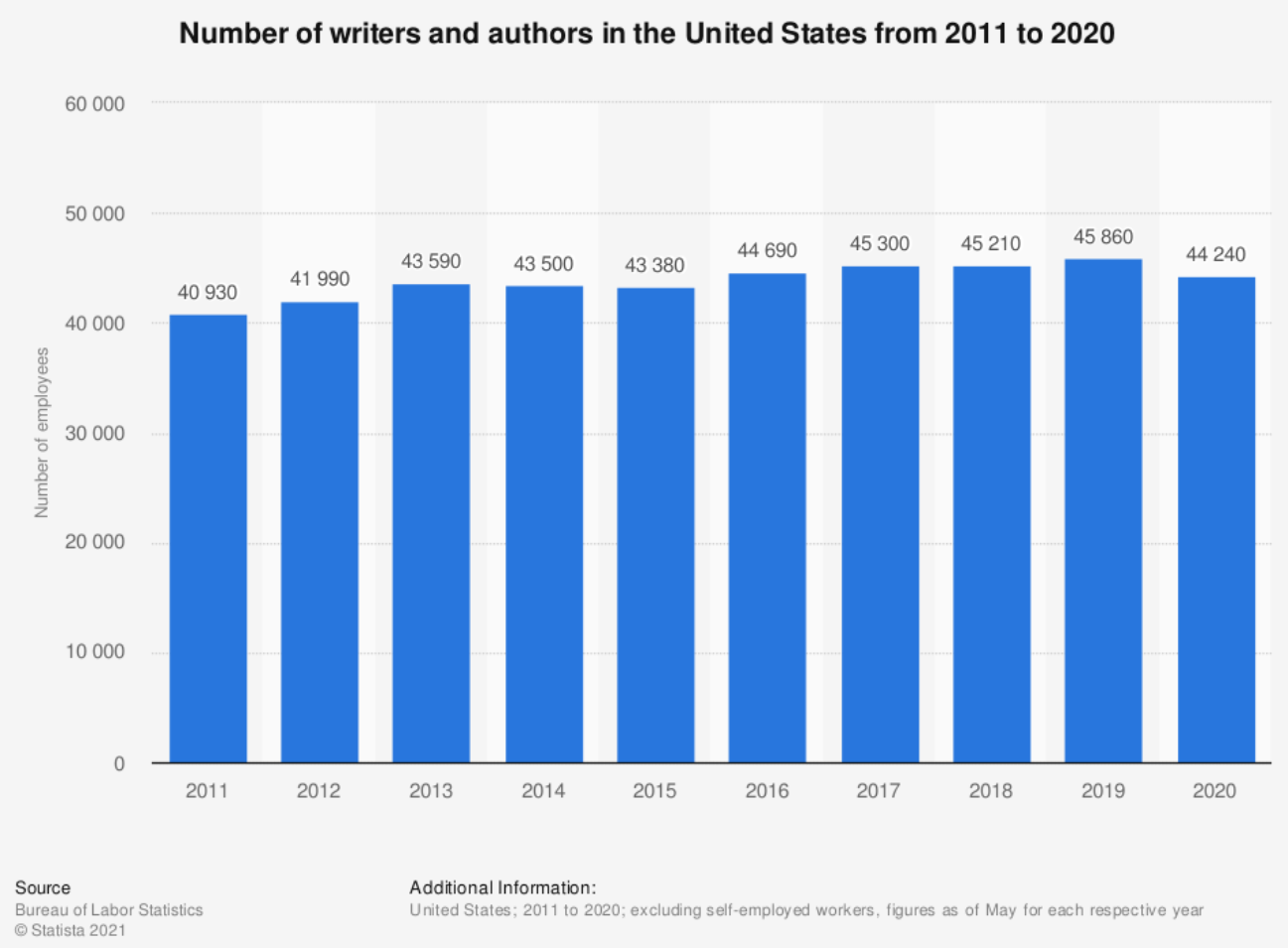

In 2020, there were 44.2k writers in the US. (This feels a lot!)

And how much do these writers and authors earn?

And lastly, the money shot.

Only 0.7% of self-published writers, 1.3% of traditionally published writers, and 5.7% of hybrid writers reported earning more than $100,000 a year from their writing.

Enough said!

What if you’re a musician though?

A way to check is that there were 16k musicians currently employed in the United States.

Well this has changed dramatically. But at least if you look back in the day, the majority of the income (were you selected) came from contract royalties. Today that’s flipped.

An interesting consequence of the flipping is that contract royalties are passive income for a piece of work, and concert income is dependent on your ability to, y’know, go do a concert. I couldn’t easily find the number of wealthy musicians to compare against, but dare I remind you of the Spotify statistic above and ask if it really could have been worse back in the day?

III

Ok. So things look harder today. But maybe the answer is that the turnover of fame is higher today? In that the lifetime of fame has decreased and we have a faster half-life today.

There definitely is a cultural argument that movie stars are a part of the yesteryear, perhaps gone the way we think of opera singers or play-actors.

This decade seems to have produced fewer certifiable movie stars than any other since the 1920s. Jennifer Lawrence was crowned America’s latest sweetheart, but she hasn’t had a hit since 2016. Melissa McCarthy and Kevin Hart are rare headliners not baptized via franchises, but they’ve suffered diminishing returns. Dwayne Johnson used his “Fast and the Furious” cred to become king of the action blockbuster, but he did so on the shoulders of a multimillion-dollar pro-wrestling career. Scene-stealer Octavia Spencer won a supporting-actress Oscar in 2011, yet she wasn’t given a lead role until 2019. Veterans like Sandra Bullock, George Clooney and Matthew McConaughey found intermittent success, but the adult-oriented movies that define their careers have grown passé. Many other top-paid performers — Robert Downey Jr., Scarlett Johansson, Chris Hemsworth — owe the bulk of their prosperity to comic-book adaptations that essentially sell themselves. Leonardo DiCaprio is arguably the only actor, male or female, to weather this decade without yielding to any of its demands.

I found plenty of anecdotes of the type for movies, music, literature, architecture and pretty much every other endeavour of human creativity (plus journalism). But since I don’t believe them all that much I’m not linking to them here to make the case in either direction. Sam had suggested maybe calculating changes in Q scores over time might be a great way to do it, but I haven’t found a good source for this yet.

I’m however still unconvinced that the half-life of fame has indeed reduced over the years, since the very surfeit of attention and connectivity we all enjoy means that, at the very least, the effects of a larger network would be felt across the spectrum. To whit:

The winners today would be much larger than the winners of yore - matthew effects make winners much larger as the size of the landscape increases

The cascades that set off a flutter of fame can be seeded much more easily - because chaotic effects resulting in runaway positive feedback loops is easier in a network which has lower entry requirements to become a “node” and smoother ability to create a “link”

The cascades that set off a flutter of infamy can also be just as easy, meaning the lifetime of a star is much less stable than it used to be. Easy come, easy go.

That’s what network theory tells me and what anecdotes seem to fill in. But if any of you have data to back this up I’d love to see it! Until then I feel that it’s kinda true that we just don’t make celebrities like we used to. (And that’s okay, but that’s a different essay).

IV

What does this all mean?

Put together, prima facie it feels like its much harder today to do any 1 thing to stand out. Except perhaps for becoming a novelist, your chances of success seem to have been better back in the day, especially compared to trying to become a youtube celebrity that all the kids seem to want to do these days.

The argument that makes most sense to me however is that it’s all additive. So while in the 90s you could try and become a musician or writer or an actor etc, today you can add becoming a youtuber or an instagram influencer to that list. This seems possible but as we saw above with the spotify info quite a lot of the new additions are cannibalisations of what used to exist before.

as the critic Leo Braudy notes, in his 1987 study, “The Frenzy of Renown,” “As each new medium of fame appears, the human image it conveys is intensified and the number of individuals celebrated expands.”

This is also true in most other aspects of human endeavour. Despite the technological leaps and new vistas we still retain several of the older jobs that used to be done. For the loss of a teller was replaced with the advent of many more programmers and banking product specialists.

But it's still really hard to get famous. It's still a magical combination of luck and talent and timing and opportunity and perseverance.

The one thing that definitely has changed is the emergence of the micro celebrity. Most prominent perhaps on twitter, where with a “mere” X0k followers you get to flex the influence muscle. But even this isn't as easy as it seems considering the sheer numbers game.

For every roon there's plenty who didn't quite make it. What it seems more suited to is as a catalyst, in that if you succeed it opens far more doors than you'd have had otherwise. It's not an end in itself as much as a better means to an end, and that too a means that has a much higher proportion of luck associated with it than that which came before.

We get seduced by the fact that some people, seemingly with no legible skill, get famous that we equate it to “oh, anyone can get famous”. But it's not so. It's a terrible mistake to not compare the actual outcomes of a process to it's list of possible outcomes.

There are pockets of clarity, like Substack (imagine how effusive I could be here). But even here the number of people making a living is far lower than the number of local journalism jobs that used to exist, though luckily more (perhaps) than the opinion journalists who used to roam free. But this has been against a backdrop of a substantial reduction in writing jobs all over the place, quite a bit of replacement and not much addition.

While there is natural turnover in these ecosystems and there’s new evolutions of each individual type of segment (streaming vs live music vs CDs), there is always a changing of the guard with these changes. That doesn't mean the total amount of opportunity has changed, only that it applies to different people now. The paths might have changed but the core is the same - people only have so much attention to give.

It has never been easier to test whether you have the potential to outshine the market. It has never been easier to do something and have the option to hit it medium to big. And it has never been harder to do just that.

Great edition. In an economics/markets/finance piece, YOU had me at "Young Thug".......☝🤘👨🎤

Having completed what I now realize perhaps was an unnecessary MBA , I was at loss as to which Gods I need to appease to hit that proverbial "success"...

Now I know it's the god of decimal points

Pray tell what sacrifice does this pagan god accept