AI risk is modern eschatology

Or how I learned to stop worrying and love AI

Birth of gods have always been a big part of our stories. Often magical, accompanied by inexplicable miracles, and incongruity. Horus was born in a cave, a birth announced by an angel. Zeus born in Crete, youngest of his divine siblings from Cronus and Rhea. These Gods are often capricious in their whims, inscrutable in their aims and close to omnipotent in their abilities. Much of our mythology revolves around the stories where these traits hit their limits.

There are also myths we ourselves have created, of man’s attempt at capturing this divine essence leading inevitably leading to catastrophe. The tale of Icarus flying too close to the sun, not knowing that his technological aid was more fragile than he thought. On the Tower of Babel, the creation of which was both hubristic and sinful, which led God to destroy it. But the most prescient might have been the tale of Adam, named by himself and made by Dr Frankenstein to be the saviour of new humanity.

A new species would bless me as its creator and source; many happy and excellent natures would owe their being to me. I might in process of time (although I now found it impossible) renew life where death had apparently devoted the body to corruption.

Adam in machine form is AGI, Artificial General Intelligence; an AI of sufficient power, will to learn, knowledge and determination that it is conscious and at the cusp of exponentially improving itself to become a superintelligence. And once it does, who is to say what its motivations are likely to be! It might treat us like cats, as Elon Musk remarked, kill us all instantly, as Eliezer Yudkowsky thinks, or anything in the middle. Experts seem to believe the forecast time to AGI (50% chance by 2059), but with 5% chance it'll be as bad as human extinction!

The only way to avert this potential catastrophe therefore is to somehow figure out a way to make a being much much smarter than us and much much more capable than us want to do things that wouldn’t cause humanity harm.

This is the field of AI alignment. The main motivator of AI alignment, or AI safety, comes from the belief that we’re essentially creating god. Or at least a being of godlike power, without perhaps the omniscience to use its omnipotence wisely. A being that treats us as means, not ends, in that like in the Eternals movie, us humans are only as important as we are in its birthing process, and only unimportant collateral afterwards. All religions have their versions of the Day of Judgement, concerned with the ways in which we will kill ourselves through hubris. AI existential risk discourse is modern eschatology.

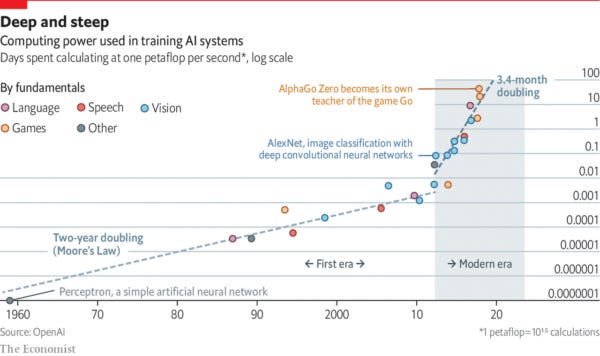

In order to get there, there are mainly two schools of thought. One school, what I call the Jeremy Clarkson school, thinks we essentially just have to throw more compute at the problem. More power, more data, more variables, more compute, more memory, and fairly similar algorithms, that’s all we need. Here we can happily argue about reinforcement learning or deep learning or whatever particular bit of optimisation math floats your boat, it’s sufficient that it’s scaled up.

The second school, for which I don’t have a pithy name, believes we have as-yet-undetermined hurdles in front of us before a true AGI presents itself. Call them the Agnostics. It’s not about whether it’s impossible in principle, as Penrose et al thinks, where there are things in the realm beyond pure computation1. But rather it’s about an understanding that, as Gary Marcus often writes, the current methods are insufficient. We need newer methods and ideas to truly push the boundaries to create systems that actually understand physics or actual reality. They’re skeptical of the specifics, should we use deep learning as it stands or add something symbolic to it, though in principle agnostic as to the possibility of the end result.

As Scott Aaronson said

The big question is whether this can be done using tweaks to the existing paradigm—analogous to how GANs, convolutional neural nets, and transformer models successfully overcame what were wrongly imagined to be limitations of neural nets—or whether an actual paradigm shift is needed this time.

The second group, identifying errors in the likes of GPT-3 or DALL-E 2, aren’t about blaming the algorithms or poking fun, or god forbid being purely incredulous at the notion of a machine actually thinking. It’s about the fact that if you teach a system purely by giving it 3rd or 4th hand knowledge, through texts created by people who learnt it from others who might have done experiments or experienced the world, that’s bound to create a game of telephone.

And we see the results. Bounded as they are within their digital prisons, there is no way for DALL-E 2 to understand what “please draw our solar system, to scale” means. While it understands what the solar system is, by understanding how we have used that phrase in the past and what else is co-located near it in the texts it’s imbibed, this isn’t sufficient to help represent a version of this reality in its vast memory matrix or to retrieve it easily.

Can this change with the help of Group 1, the Jeremy Clarksons? I suppose so. We’ve seen the versions of GPT improve leaps and bounds. The first time I compared GPT-2 with my then 3-year old, it made eerily similar mistakes. Now, with GPT-3, it shows brand new mistakes.

Does the fact that the mistakes have changed show progress? Yes. How much credence should one give to the fact that it does seem to keep improving, at least thus far? Unclear. Is the fact that it’s showing progress sufficient for us to “believe” its output? No.

We’re back in the p-zombie problem that philosophers have played with for so long. How much can we infer about the inner workings of a machine if we can only see its behaviour? In this instance, considering the errors it makes consistently show that it’s able to recognise deeper patterns than the prior version, but consistently make new errors where it clearly doesn’t understand the actual physical reality of the world, we can’t trust it!

Saying “new versions have improved over old versions” is highly uncontroversial, as is saying “newer versions might never get to human, let alone superhuman, levels”. The steps to get there are unclear (again, if you’re not in the Jeremy Clarkson group), and making plans for this ultimate eventuality seems mired in opacity, both with respect to what we can know and what we can do.

AI today is an idiot savant. Everyone can see that. Now imagine a world where they become better. Where they are able to solve multiple types of challenges, becoming more than mere tools. Where they are able to autonomously be able to run entire experiments end to end.

In order to get there though, there seem to be two major turning points.

There will need to be planning AIs, which are capable to putting together complex plans and combining multiple capabilities, to achieve an objective

These AIs will have the ability to lie to us about what it is actually doing - whether that is intentional or just through pure goodharting

How likely are these? It depends on how strongly you take the evidence of research advances that have happened recently. We’ve started seeing models be able to do multiple tasks, not just predict text or play games but both. We’ve started to see emergent abilities from language models. We’ve also started to see specification gaming, where a reinforcement learning agent finds shortcuts to get the reward instead of completing the task as we’d have wanted. There are reams of writings on the likelihoods of all these events, with multiple probabilities attached to each idea, though to me it sounds suspiciously like people using “60%” instead of “quite likely”, and with roughly as much epistemic rigour.

The broader worry is that with sufficient training and complexity, AI will be able to generate its own hypotheses and test them, be able to integrate knowledge about the world from seeing external information (the idea that from three frames of video it would deduce the general theory of relativity), and most worryingly be able to do all of this without necessarily giving us a glimpse of what it's actually thinking!

The seeming inevitability of a destination shouldn’t seduce us into becoming fatalistic. The journey moulds the destination. It does so in the most mundane of life’s adventures, let alone this, the grandest of them all.

Once you believe in the inevitability of the existence of a powerful enough machine, one that in theory could replicate all of our thought processes and debates and conclusions, then of course the only path you can take is to find a way to make its goals the same as yours. Once we’ve agreed with each other that we are indeed building God, then we better find a way to make God love us.

This is the crux from which is born the AI alignment movement. The literature here is as vast as it is confusing, because people keep calling things AI safety or AI alignment while meaning anything from de-biasing algorithms to not be racist to finding that perfect mathematical equation to know that future AI won’t ever hurt us. The difference in ensuring that a photo tagging algorithm recognises faces of all colour however is qualitatively different to ensuring a superhuman entity will agree with our morality and not lie to us.

To make this easier, there is a really good overview of the various alignment approaches that people have taken, and how they break down based on the problems they’re solving. Looking at the overview one sees a clear trend between what I’d have previously assumed to be good old fashioned AI creation, and theoretical approaches that seem to be trying to reverse engineer morality.

AI safety research is either highly theoretical seventh dimension chess about potential future states, with math, or specific research on things like human-interpretability of machine learning algorithms which are, essentially, inseparable from actual AI research. It’s also an incredibly useful nomenclature for a team to tell everyone you’re actually being careful while doing whatever’s most useful to get results!

If you don’t do a Penrose and assume a non-computational model of consciousness, then pretty clearly you’ve granted the premise that one could, in theory, create an agent that solves problems at least as well as a human can. If we’re not magical, then there’s no reason to assume magic to recreate us.

One of the approaches taken to assess the viability of this is to see how hard it is to simulate a human brain (100 trillion synaptic connections and 100 billion neurons) and 100s of chemicals mediating said transmission, and the environment surrounding that digital person to enable the simulation to act with reasonable accuracy, we might have just theorised a digital upload of a brain.

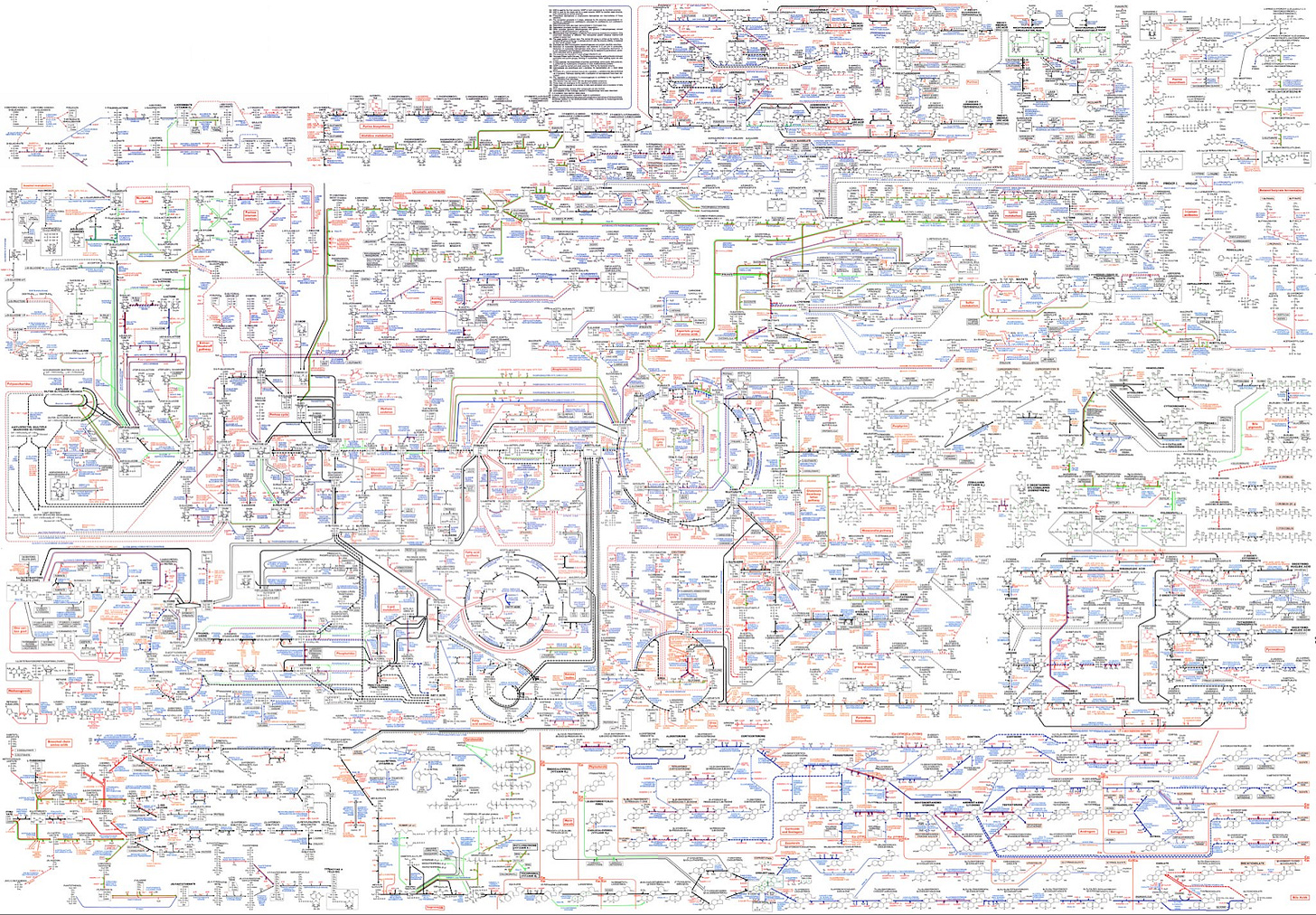

This, for instance, is the human metabolic pathway, that laid out looks so complicated that I despair at our ability to code it into a system that doesn’t immediately crash.

Is this impossible? No. As David Deutsch says, as long as it isn’t forbidden by the laws of physics it’s allowed. This is not impossible. But is it feasible? Feasible in the next 20 years? 100? Nobody knows. We can try and assign probabilities to this uncertainty, but even with a reductionist approach of trying to break this down into understandable chunks, we’re still throwing darts in the dark.

If the mechanism of operation inside the brain is purely attributable to the number of synapses and their firing, then it might be as close as everyone thinks. If it requires an understanding of various physical, chemical and biological processes, many of which are analog rather than digital (synapse firing not being purely a binary 0 or 1 but rather depends on the strength and speed of the impulse) then this gets orders of magnitude more complicated. If each neuron is a mini-computer rather than the flipping of a number in an impossibly large matrix, it gets more complicated still!

Add to this the fact that training is quite expensive. GPT-3 took more than a month and cost around 936 MWh. Probably on the order of $5 million. By itself this means that as the costs fall and ability increases we’ll be able to keep training larger models, however it also means that we’re probably a while away from casually creating new models without a substantial shift in our energy infrastructure. Considering the alternative AGIs that exist today and our reproductive capabilities compared to the energy expenditure, there’s a-ways to go.

Now, even if it’s feasible, is this going to result in widespread catastrophe? We don’t know that either. I do know that today’s top-notch AI systems, fed carefully the data of the entire world and trained with algorithms finely tuned to answer our questions and satisfy our needs, supported with the most incredible impetus humankind has ever discovered, to make money, don’t seem to be all that good. Google’s Page 2 sucks, and its not because there are only 7 items that answers someone’s question across the entire wed. As is anyone using Amazon’s recommendations for, well, anything!

While we have amazing results like Dall-e 2 and GPT-3 stunning us as proof-of-concepts with incredible abilities, we have a dearth of any of these that actually seems to work in the real world. Yes, this will change, and the open sourcing of Stable Diffusion will help that. And I have to emphasise that I am, in many ways, an AI accelerationist who would love to see it get more powerful and therefore useful. But it’s fair to say that if you draw a line from “decent enough at doing some anomaly analysis” to “fully simulated brain of Einstein”, the current capabilities are depressingly close to the starting point.

But we’re back to assuming God. First postulating that because something can improve it will improve, and then deciding the downsides of that improvement will lead to our very extinction, feels like putting the cart well before the horse. You can’t just skip the middle 100 steps in predicting the future while simultaneously believing everything else will just stay the same.

We should be focusing on areas where the current AIs fall well short and see if we can’t make them more aligned to what we want to see. Whether that’s accuracy (searches and recommendations, anomaly analysis results), better data for representation (real gathered data and synthetic), or an understanding of errors that might creep up in any AI system, this feels like a great place for the smart folks to be spending time on. And there is no shortage of these systems - we have multiple areas where the usage of AI has caused significant damage because the AI doesn’t understand reality, as this example of rejection of life insurance shows.

AI work isn’t philanthropic, even if you couch it as the reverse of an extinction risk. Analogies aren’t great reasoning tools when you apply it to the intellectual equivalent of Drake Equation where half the variables are themselves placeholders. The only way to prevent our so-called doom is to actually do the hard work of creating the AI and troubleshooting it every step of the way.

This will simultaneously make AI safer to use, literally in the cases of self-driving cars or justice system algos, but also embedding a deeper sense of humanity into the process. Then perhaps by the time we design something capable to creating futuristic nanotechnology with the power to instantly turn us all into paperclips, it will understand why doing that is immoral.

We can talk about pivotal acts all we want, and imagine vague scenarios that will lead to an all-powerful AI capable of so much that it can simulate quantum-biological processes with perfect accuracy, which is somehow oblivious to the needs of humanity, enough so that it’s happy to turn everything it sees into paperclips, but it’s so incredibly important to point out that this is a destruction myth. It’s apocalypticism crowdwriting its own biography.

Frankenstein is perhaps the wrong myth for our time. A better myth to keep in mind would be Faust. It was his own temptation to use the ultimate power for evil that led him astray. When we do choose to build ever more powerful tools to help us think we have to use them wisely, like not choosing to use error-ridden algorithmic processes to override human concerns when it comes to things like setting bail or approving life insurance.

This feels like a moral choice rather than an ineffable truth about life though. It’s something we can choose. There are no shortcuts to solving the ultimate problems of life, it’s painstaking iteration all the way.

Being named after a term from Hofstadter’s book, it’s only sensible that the computational theory of mind makes an appearance in the essays here.

"...but it’s so incredibly important to point out that this is a destruction myth. It’s apocalypticism crowdwriting its own biography."

YES! It's not simply the belief, but all the activity devoted to predicting when AGI will happen, the surveys and the studies with the Rube Goldberg reasoning over order-of-magnitude guesstimates. This is epistemic theatre. And the millions of dollars being poured into this activity. This is cargo cult behavior. There may not be a Jim Jones, or a jungle compound, much less toxic fruit punch, but this is a high-tech millennial cult. And it's all be conducted in the name of rationality.

I'm not sure what the argument here is.

People have predicted bad things/apocalypses in the last, they didn't happen, so AI is fine?

The core arguments of those who are concerned about AI isn't that "something could go very wrong", it's that:

1) Alignment is extremely difficult, even in principle (of which there are many, many extensive arguments for, not least by MIRI)

2) We have no reliable method of telling when we cross over the threshold to where it could be dangerous, thereby making it too late for troubleshooting

The above doesn't seem to have any specific counterarguments to those concerns.

I'm not even personally an AGI guy (for what it's worth, my donations go to global poverty/health), but the arguments are much stronger than you present them, and worth addressing directly.