Talent is the defining problem of our times. Finding talent, developing talent, retaining talent, fostering talent, compensation of talent. Whether you’re a two person startup, or an investor, or a large established company, or a government department, you’re dealing with this problem.

.. the unavailability of needed skills and talent is judged to be the number one threat to businesses. When we speak to CEOs, nonprofit directors, or venture capitalists, lack of proper talent—and how to go about finding more of it—is an obsessive concern of theirs.

The book from Tyler Cowen and Daniel Gross looks at the identification part of this phenomenon. In a world where talent exists but is unequally distribution, how can you find them is the question that animates the book.

We focus on a very specific kind of talent in this book—namely, talent with a creative spark—and that is where the bureaucratic approach is most deadly. In referring to the creative spark, we mean people who generate new ideas, start new institutions, develop new methods for executing on known products, lead intellectual or charitable movements, or inspire others by their very presence, leadership, and charisma, regardless of the context.

There are many ways to read this book, all equally valid. There’s a way to view this as an ode to talent and its multifaceted presentation. There’s another that effectively dismantles the currently prevailing methods of talent identification as unsuitable for creative talent. Another that tries to identify tips and tricks to moneyball underrated talent. And another that tries to establish the real world cultural setups that produce and encourage great talent. And one, inevitable in a Cowen book, which talks about cultural contexts and how they affect the way talent presents.

But if we zoom out, the book essentially has two questions at its heart.

What are the best techniques and mental models to identify top talent? And what stops you today from identifying them?

What are the broad cultural axes to understand people with different backgrounds better?

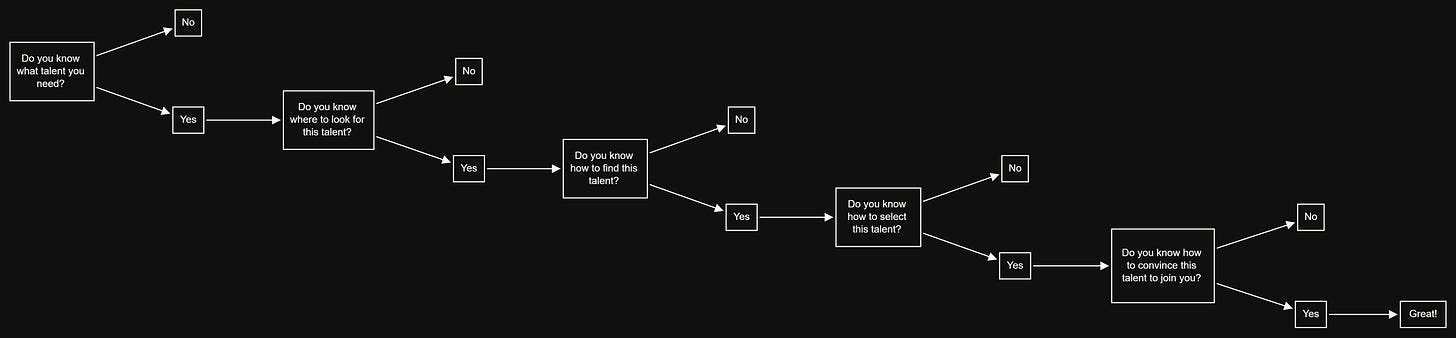

The best way to understand the book, to me, is as a journey through a funnel. As traveling through the sequence of decisions you have to make when you think about how to identify or recruit people.

The argument that Tyler and Daniel make is that our default state is to find an offramp from this line of questioning at various choke-points and to use bureaucracy or lazy generalisations to get an answer.

For instance, the question of “Do you know where to look for this talent” gets shortcut into credentialism or recruiting solely from referrals. The question of “Do you know what talent you need” itself might be shortcut by looking only at what others have and trying to copy that. The question of “Do you know how to select for this talent” becomes a shorthand for trick questions or case studies or, god forbid, stress interviews.

The answer to how we can get out of this Gordian knot combines 3 strands, each of which is relatively well understood and sensible, but all of which are hard to do in practice.

Don't fall prey to preestablished notions of identifying outlier talent - create your own view

Ask different questions and probe heavily to see how the person acts in real life; have a conversation in other words

Keep the cultural background, yours and others, in mind so you can contextualise their responses

In other words, the advice for the interviewer and the interviewee is the same - to thine own self be true. The fact that this was said by Polonius need not give us pause to use it as a better basis for understanding each other. When asked for career advice I used to tell people not to be an instrumental variable, which is similar. Or Kant’s adage of not treating people as means but as an end also echoes a similar preoccupation to see the entire self.

The places where the book works best are when it demolishes widely held ideas about where talent is found. Such as curate your own pool to fish in - via a podcast/ writing/ intellectual network/ community. Or look for examples of grit and perseverance over pure IQ, at least at the margin.

Demolishing these is a huge role for a book (or indeed a conversation) that tries to question the things you take for granted. There’s also a role for someone to tell you “hey, you should probably look at hiring not just as adding bodies, but rather be more mindful”. That’s where the book shines.

After all regardless of how you think about your process, the one you’ve developed painstakingly, it’s hard to step away from inherent bias or even credentialism (or anti-credentialism acting as counter signalling).

For all the resources you put into scouting, interviewing, and trying to suss out the better candidates, there is no real substitute for having a good or great pool of candidates. That will depend on your soft networks, ones that you and your institutions have been cultivating for years (you hope).

If you, however, were to try copy the recommendations (which to be clear the authors don’t suggest) you’d probably end up doing worse than normal, because you’re not Tyler. Instead, its more about asking the question of what you’re good at, where your audience is today, and where you should focus when hiring people - i.e., to build your own unique advantage. Just like the decision tree up top.

It's a book that asks you to keep an open mind and destroy your preconceptions than one that gives you a clear path to hiring von Neumanns.

My immediate reaction to the book was to go nah, this wouldn’t make any sense to do in real life. This changed later, but it came about because the ability to conduct interviews and talent search the way the book talks is highly idiosyncratic, and impossible to define or explain to someone else.

For instance, the best interview technique I’ve seen to find highly motivated, engaged, employees is funnily enough (or not) that I saw at McKinsey. There’s a case study in there, but that feels almost pro forma. Almost everyone who gets to the interview does it well enough, whether through innate ability or coaching and practice. But that’s fine, we want people in real life to practice for what they want to achieve!

The more interesting part is the personal interview. The part where Tyler asks questions like “what open tabs do you have on your browser” and tries to glean the answers from it. Here the Mckinsey technique, which I stress I have not seen used almost anywhere else in the corporate world, is to let the candidate choose a circumstance that shows grit, or creativity, or perseverance, or working with difficult colleagues, and let them tell you the story.

You then spend the next 20-25 minutes trying to go deeper into that story, to test that it says what the candidate thinks it says, to analyse whether she actually was pivotal in that story, and to assess whether the story is true! And Tyler and Daniel think this is a helpful way too, hinted obliquely.

…it should be a question you really want to know the answer to. So if the person worked in a ball bearings factory in Cleveland, ask yourself if you care more about ball bearings or more about Cleveland. And your follow-up questions should also reflect real interests of yours.

I have found this to be incredibly insightful, especially since most people don’t like going too much into detail about things they’ve done. It’s not to get specific information about subject matter proficiency, but to get a sense of how they think and how they speak and how they act with others. All of which are crucial factors to get a sense of how they get things done in the world!

Could you replace this with a conversation around “how ambitious are you”? Sure, I don’t see why not. It would be harder, perhaps, to glean useful insights from that conversation, but that’s only because we have no practice with it.

This would maybe not necessarily surface iconoclasts who blaze their own path individually, perhaps, but it would definitely surface followership. This maybe wouldn’t surface an individual’s stark ability to paint, say, the Starry Night, but it would surface Michelangelo’s ability to design and get a team to follow his vision.

Also, there is a certain group of people, and I count myself amongst them, who are infovores. I like knowing weird facts, and thinking through esoteric thought experiments, learning about cultural codes that are interesting but perhaps not actionable, and in general living a life of the mind.

Some of this does help me in becoming better at my job, whether as an investor today or as an advisor in the past. The counterfactual however is murky because I also know tons of people who don’t do this at all and are also good as investors and advisors and entrepreneurs.

When I’m looking to hire another investor or advisor, I’m acutely aware that if I were to focus too much on their level of interest in this type of intellectual pursuits, I’d be left with copies of people who look an awful lot like me. This is the difference between Twitter curation Vs real-world hiring. In the world I look for competence, current and future, as opposed to indirect proxies for that competence.

In many ways, the world of investing is a good proxy to think about this particular form of talent. And seen in that way, you do get to see that the titans of this industry have spanned from Bezos to Gates to Zuckerberg to Chesky to Collison to Jobs to Kalanick. These individuals are not alike, except in their passion to create something de novo using the gifts that they were given, whether that is obsessiveness in Gates or design mindedness in Jobs or sheer chutzpah in Kalanick.

What this also means is that if you were aiming to pick them ante bellum then you would have to throw out your playbook and perhaps just index on sheer ability to will a new world order into existence.

“What do you care about and why do you care about it” are the core questions you’re trying to get an answer to, that you ask again and again and again and again to get a “true” answer to this question. Bear in mind it doesn’t matter if the answer is “I have megalomaniacal ambition”, as long as you believe that motivation will provide enough of a driver to do amazing things!

In my own time in venture capital, the best investment I ever made happened due to techniques in this line of questioning. I invested in Hibob in its seed+ round, which performed multiples better than our bull case scenarios. Ronni, the CEO, had demonstrated ability from a previous stint as CEO of a successful venture backed company, and hunger for success since that company hadn't been a unicorn. He was ambitious and hell-bent on learning, while assembling a team around himself with expediency and ruthlessness. I remember being chided rather severely after the first meeting for being excited about investing in it, since it was early and had no metrics.

To me, the distilled understanding of the questions you ask should elicit:

Does this person care about the subject they're talking about?

Do they care to learn and spend effort learning?

Are they getting better at each interaction across any dimension?

And in the case of leadership roles: Can they get others to follow them?

Bear in mind that this would fail the normal test of interviews, regarding the understanding of the subject material or long-standing relevance. Ronni had never looked at consumer facing tech on the application layer, nor even looked at HR software until a few months before. He wore his ignorance proudly, and said in fact he gets to learn which is why he was doing it. What gives me a tad more confidence is that there are four other companies I had a similar reaction to - one sold for $450m, one is at $12B as of last valuation, one worth $3B and another that's stagnant.

This is also what changed by mind. What this did mean is that the method outlined in Talent clearly works, even though the questions I'd asked and the responses were completely different to the ones Tyler and Daniel outlined in the book.

The biggest question that I was left with immediately having read the book was, if you’re not Tyler Cowen or Daniel Gross, can these techniques work? My first reaction as I said was a rather emphatic no, but I’ve sat on this review for a few weeks and now I think I was wrong. It’s that these techniques clearly do work, just that when they work it looks closer to rhyming than copying.

You can’t just use the questions outlined at the end and get much mileage out of them. But you can benefit from thinking through how you might come up with similar questions and figure out how to get answers to them. The book serves less as an instruction manual, but more like the ladder early Wittgenstein would have you throw away after climbing it.

In fact I found the questions as outlined in the book serve neatly as conversation starters and thought experiments, rather than something to be followed religiously. In fact I would wager that if you were the use those questions your results would be worse than average, because the ability to get signal from those questions are a function of being Tyler Cowen and Daniel Gross who have experience with asking the question, hearing the answers, and putting them in a particular interview context.

The questions act kind of like divination sticks. They're not individually very useful perhaps, but you might have developed ways of reading people's reactions to those questions, which is the truly valuable implicit skill. These might be around hobbies, or social situational awareness, or practical brain teasers, or reframing business problems (my favourite), or common household chores.

Yes you might have specific tips around what not to pay attention to in zoom meetings vs real life, or whether the background says something interesting about the person, but it’s also a function of the fact that you’re being mindful about the meeting in the first place and not thinking about the lunch afterwards.

One of the core conclusions of the book funnily enough is that it's not about hiring at all, but about a way of living. If you think of talent as a spike in some core attribute, and that a lot of people have it who are often overlooked, then identifying and encouraging them are extraordinarily good things to do. "Raising their aspiration” in other words. For yourself (because it will be a far better life) and for them (because the trajectory of their life will change). And its as close a method as exists to find true relationships too, which are much scarcer in the absence of these conversations once outside, say, university.

And as a bonus, you might be able to hire yourself some excellent oddballs. As an oddball myself, I find that encouraging.

> infovores. I like knowing weird facts, and thinking through esoteric thought experiments, learning about cultural codes that are interesting but perhaps not actionable, and in general living a life of the mind.

> Some of this does help me in becoming better at my job, whether as an investor today or as an advisor in the past. The counterfactual however is murky because I also know tons of people who don’t do this at all and are also good as investors and advisors and entrepreneurs.

Not the core point here, but this is what I personally find most difficult about identify talented people.

Whatever traits make others talented will be completely illegible to me in almost every single scenario, the core traits which I'd attribute as giving me my abilities will be hardly visible or completely missing in them.

Yet in practice, best on results I've seen across many metrics, it's obvious these traits are not a prerequisite for talent nor do they even get close to guaranteeing it

“The book serves less as an instruction manual, but more like the ladder early Wittgenstein would have you throw away after climbing it.”

Beautiful line.