A little less conversation, a little more action

Elvis Presley

Making choices is core to being human. From choosing what to play with as kids to choosing what to study as young adults to choosing where to work to choosing whom to go out with, we’re mired in choices from the moment we’re born to the moment we die. In almost all of those choices we are meant to make, both nature and nurture limit the menu in front of us. Most of us don’t choose to not become an astronaut or choose to not become an underwater oil rig diver, those choices just wither away in the branches of the tree of life as we move forward.

And yet, the hope remains of choosing the best option; choosing the best ice cream, choosing the best music to listen to, choosing the best major in college, choosing the best job. All of which rely on some version of ranking some criteria and maximising the output. But because the truth is we don't live in small villages anymore, the infinitude of choices overwhelm as we even glimpse at the true breadth. Thus is born and dies the spirit of utilitarianism that is inherent in all of us.

Once you're a young adult one tends to learn more about the world and want to do what young adults do. Which, in most cases for the most ambitious folks, turns out to be an incredible urge to have an indelible impact on the world. This feeling of slight vacuousness combined with incredible energy and a need for a community that understands them doing extraordinary work, has been fodder for all sorts of organisations to find talent. Have a look at this list from my friend Paul Millerd on various promises companies make in their recruitment pitches.

All organisations that run on the basis of the ambition of the young make pretty much the same sales pitch. If it’s being explicitly pushed towards making the world a better place, that’s a good thing.

However, the choices you make are circumscribed by that which one can see. Complexity, as always, is the undoing of God's eye view of optimisation for us mere mortals. As the world gets larger it gets harder to make the best choice. Without a unique probability distribution, decisions can no longer be made by maximising expected utility.

Just like we didn't know how best to organise our economy and distribute resources in order to get the best possible outcome, trying combinations of market economies and central planning, we also don't know how best to employ our resources to do the most good in the world. And this is the heart of my contention with the world of Effective Altruism, or EA.

Since we don’t actually know what the future holds, we have to find out, to estimate. Which is why today, a large part of EA is essentially McKinsey for NGOs. They analyse, research, report and advise on the correct courses of action, backed by data where its available and guesswork where its not, aiming to reduce the complexity of the world into something more legible. In a static world, this approach is extremely sensible. In a dynamic world, we need something more agile. And a recalcitrant trait to focus on shutting up and multiplying leads to the inevitable prioritisation of things which are neither E nor A.

Because the world we live in isn’t one that easily constraints itself to this analysis. We all live under conditions of Knightian uncertainty.

according to Knight, risk applies to situations where we do not know the outcome of a given situation, but can accurately measure the odds. Uncertainty, on the other hand, applies to situations where we cannot know all the information we need in order to set accurate odds in the first place

Decisions made under this condition have to deal with the fact that we can’t know the distribution of all possible future states, which means even if we could look at all the likely outcomes we might not be able to optimise for the best outcomes.

The problem with Knightian uncertainty is that more research doesn’t necessarily lead to a better answer. Rumsfeldian unknown unknowns will ruin your calculations. And because of this, EA has the same failure modes as McKinsey does, which is that despite highly talented individuals joining it, its impact on the world is a fraction of what it should be.

This means you’re stuck in the shallow, legible end of the pool, tinkering at the edges and maybe increasing the efficiency of the system, while not being a part of transformational changes in society! Which means most of the interesting things to benefit humanity are currently out of scope, like working for economic or technological growth. It also means the only way through is to radically increase its focus on doing rather than prioritising, thinking and researching.

McKinsey for NGOs

EA does prioritization very well. Give it a set of options and they analyse them to the nth degree, assign numbers where they can, assign probabilities of uncertainty where they can't, create calculations of QALY benefits, and compare the list. The best example to me is this excellent and extremely well researched article on shrimp welfare. This is EA’s strength, and this rigour was lacking from much of the philanthropic world (except maybe places like Gates Foundation, which also used consulting firms)!

At McKinsey when I was there, life was much the same, and we’d often compare complex alternatives in an Impact Vs Tractability matrix. Measuring Impact and Tractability would naturally entail a large degree of guesswork, but the alternative is throwing darts at a board and going with one's gut.

Sometimes this is useful. And sometimes it’s telling AT&T the cellphone market will be 900k devices in 2000 instead of 100m.

This is because the Knightian uncertainty is high! And the output is often a document to explain what you found to convince others, stridently trying to create convincing pitches to each other about the cause areas they’re most passionate about.

And yet, and yet, there's a reason McKinsey isn't known for being extraordinarily innovative in its prescriptions. It's not because of lack of intellectual rigour or the will to do it, it's that the organisational ethos lends itself to premature and rigorous optimisation, to doing better the things they can measure. Just as its job is to shore up the uncertainties involved in making choices between options that are semi-defined, it is often blind to the potential for de novo creation.

To me this is at the heart of my disagreement with EA.

I’m not an EA not because of a fundamental issue with altruism, or indeed an effective version of it, or even the cold utilitarian calculus leading me astray, but because I feel the mechanism by which EA tries to impact the world is, in some core ways, ineffectual. Its core methodology, of figuring out and then doing the thing that does the “most good” isn’t all that effective, considering the fact that the greatest poverty alleviation and life improvement we’ve seen have come from economic growth and development.

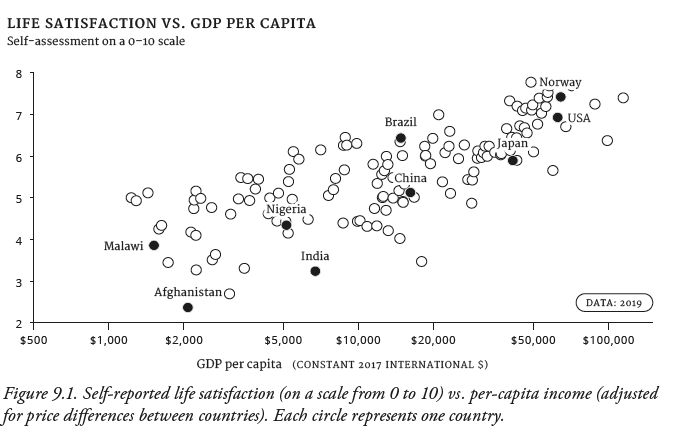

EA therefore is playing an incredibly important role mainly focusing on raising our baseline. It treats as the primary good the fact that minimising suffering is good. Its counterpart therefore might be the newly forming field of Progress Studies, who are much more focused on doing the necessary experiments to increase the pie, starting with the argument that economic growth has been the only silver bullet in our arsenal historically, and that’s where we ought to focus.

The difference is that the shore up the bottom strategy tries to push the entire curve up but mainly works at the long tail. The other is what's used amongst the top quintiles and deciles, which help push up the top end of the curve. And the strategies they make eventually trickle down and become common knowledge, and once diffused stop being sources of alpha.

The idea of finding new “cause areas” to bring to general consciousness can be good, much like trying to find new startups is good. However it only becomes truly useful once its actioned, and in order to do that you need something much closer to a market economy that prioritises action, than a research economy that prioritises measurement1.

We are bad at this in government, we’re bad at it in social sciences, we’re bad at it in the real sciences as often as not, we’re bad at it in grant giving and we’re bad at it in venture capital investments. It strikes me that beyond a barrier of plausibility, we’re just bad at recognising a 0.1% chance event from a 0.00001% chance event, or even from a 1% chance event.

What this means is that the focus on solving “big important problems” becomes a problem of “finding the big important problem”, and we’re back to dedicating large amounts of administrative and bureaucratic effort in figuring out what work to do. It’s worth noting that the biggest impacts of EA have really been in areas like GiveDirectly, which tries to reduce or eliminate that very burden so life’s not so totalising.

This approach by its very nature restricts its longevity.

If people spend a decade or more in areas with no real payoffs or real benefits leaking into the real world, then you’re burning out the smart people today and creating a much bigger barrier to attracting the next generation. Burnout by itself doesn’t sound like a big problem to me, many large successful organisations very happily use burnout as fuel to their growth, but burnout without a clear payoff elsewhere is a no-win situation.

If an ever larger chunk of the conversation around EA revolves around its focus on the low-probability-high-impact areas, that will fundamentally distort both the experience of existing EAs and future EAs who want to join it. Yes, preventing biorisk at 0.1% chance is important, but you better also have enough clout that when it fails (as it will 999 times out of 1000), you’re not just a demoralised husk left behind.

Economic growth is the silver bullet

On what actually what has actually helped in doing the most good, we do have some benefit of hindsight. The past century is known as part of the Information Age. Or the Age of Globalisation. But when we look at the past century one thing that jumps out is the extraordinary reduction in human suffering.

Poverty isn't the same as suffering of course, but they're awfully well correlated.

When we think about the stated ambition of reducing human suffering or increasing human happiness, if the options are to identify the sources of suffering and to eliminate them, whether that's disease or poverty, we see direct courses of action. You're one step removed from making your dollar truly count.

But the chart tells a different story. The biggest suffering elimination effort in the history of the world happened in the latter half of the 20th century, where China got wealthier. It moved 600 million people, more than the population of the planet a century or so ago, out of abject poverty. This is remarkable!

This is also something that wouldn't have happened nearly as fast or as much had we looked at those individual citizens and tried various versions of redistribution. We might have been able to kickstart some form of bottom-up ability for some of them to try building things they dreamt of, but it wouldn’t have been easy. It wouldn’t have had the enormous power of an entire state upping its capabilities and providing the strong base that drives growth.

The growth we saw came from a market economy, from liberating larger portions of humanity to pursue their visions of economic freedom. And this only came from an explicit realisation that we can’t guide the economy top down.

While in a resource constrained environment I understand why the giving had to be focused on areas which are marginal (because there’s only so much), neglected (otherwise you’re not having counterfactual impact) and tractable (obviously). Which moves the goalposts enough that you both identify the major areas which need to be worked on, and also eliminate the ones where you think enough work is being done.

But this too expects a huge degree of precognition that the decision makers collectively possess. It’s being currently solved for by a larger component of democratic norm for people trying to find new cause areas or finding how to serve them better, though its a far cry from, say, Y Combinator which focuses on action.

The only way we have figured out how to solve this cognitive overload is by not deciding this at the top. Focusing on neglectedness is like trying to focus on a new niche to start a company in. That’s traditionally not how you identify what become the best ideas.

Solving legibility

Action and iteration are the best ways we’ve found to solve big problems. Just as startups provide this impetus in the commercial world, EA should help provide this impetus in the aid world. But because the focus is on fighting the dragons of uncertainty, EA is stuck focusing on areas where it can shut up and multiply.

If we look at its greatest successes, such as GiveDirectly, those have been successes born of simplicity, legibility and exceptional value created. Those achievements stand true regardless of whether those are indeed the “best” ways to spend that money.

This seems partly why a large part of EA aims to solve negative externalities - remove xrisk, reduce suffering, reduce short-term thinking - rather than actively focusing on creating positive impacts. It focuses on areas where it can either create defined measurements or create highly unspecific (not even false) Drake Equations.

It’s the Scylla-Charybdis of choices. Either EA can completely open up its decision making process, saying do good however you can, including through startups and lobbying and research and exploration and fiction and poetry and community organising, or it restricts to the areas it calculates as most important while ensuring the community it created remains alive and engaged!

(I wrote tongue in cheek that EA should sponsor science fiction, because that is upstream of the motivation for so many of the people who have fundamentally reshaped the world. But that’s not the sort of thing that gets funded either, because it’s highly illegible.)

If Bill Gates hadn’t started his Foundation until now, he would have had $500 Billion to give away, instead of 20% of that. Was that the right decision?

Or imagine you have a choice. You could give $10k to EA and save 2-3 lives. Or you could invest that money. With the investment you save 10 lives in 30 years, which at a 3% discount rate still comes out to more, at 4 lives. Which do you choose? If you put a discount rate on future lives you could solve for the equilibrium. But the uncertainty is Knightian! We can't reasonably know or predict the outcome.

What if we all collectively invest the capital, which increases the growth rate of the economy, which makes everyone wealthier? We know that if you’re above median income your life expectancy is higher. If you move from poorest 1% to richest 1% it is 14.6 years extra. That’s 15-16% higher! Which means if you manage to move a chunk of people up the income ranks, as the country gets wealthier, there is a substantial benefit to health and life expectancy!

The point is not just that you can’t reason your way through all permutations of the future. The point is the choices are not necessarily compatible or comparable, but we choose ethical systems to allocate our resources anyway.

From revealed preference, it’s probably some combination of utilitarianism (invest if the IRR is greater than 17%), deontology (we should help the drowning child if we see her) and virtue ethics (I should give 10% of my earnings because that’s the right thing to do).

A combination of these three will result in something resembling the modern system - where you can run a giant crypto hedge fund and do good with that money. Or where people donate their money, time and energy to help people they have never seen or met, and where people donate their kidneys to strangers. It bears repeating - people literally donate their kidneys to strangers! The individual actions of EA folks are nothing short of exemplary (except for nooks where I disagree)!

But the failure mode of centralisation from guessing at various futures and working to fix it rears high. Imagine if a single venture capital firm were to be charged with identifying and investing in the best companies of the future. It would be an abject failure. It is only through the cultivation of 1000s of VC firms, with widely varying lenses and investment styles and sourcing networks and diligence methods that we are able to get to anything resembling a functioning market for identifying future performance.

The solution: Build a lasting city

There are essays about how EA isn’t all command and control and there’s heterogeneity of opinions. On the one hand they’re right because it’s not like Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation where there’s a clear leader at the top. But it’s also not like the different organisations under the EA umbrella are pursuing drastically different ideas of what “do the most good you can” is - they’re singing from the same hymn book. It has many heads, but the same body.

Money being fungible, there are a lot of ways to accomplish the goal of doing the most good you can. Funding to eradicate malaria sounds awfully close to funding to create mRNA vaccines, as Gates Foundation did. Fighting global catastrophic risks through advocating for asteroid defense is awfully close to building space colonies or settling Mars. Except the first happens to fall into an “EA” bucket and the latter falls into “billionaires with dreams” bucket or the “venture capital” bucket.

The point is not just that the categories were made for man, but that fulfilling an overarching purpose requires a plurality of attempts2.

The answer is that EA needs to combine these to create a city. It should be wildly more open to ideas that have the prospect of making humanity better, even if it doesn’t pass the immediate QALY inspection. The true strength of EA is that it attracts some of the brightest and most talented people to its fold. So use that!

The only way to fight through Knightian uncertainty is through taking action and iterated improvement. For wicked problems, the only way to find good solutions is to jump in. Like with every startup, the only way to achieve success is to start the startup, since the pivots and changes and edits and the general path that a company takes from an idea to a successful company are unknowable and unchartable from the beginning.

Considering the reams of text written about prediction markets the largest chunk of learning has actually come from doing them, like Metaculus of Manifold. This is the benefit of bias for action.

Maybe run prediction markets on what the highest impact investments should be and allocate funding on the basis of people putting money (votes) where their mouth (opinion) is. This would help remove the centralised element of trying to figure out which things to fund and rather see how the city itself flourishes. It’s the only way to have both “individuals work on their best guesses on how to do most good” and “we can’t solve every problem that the world faces top down”.

EA helps give smart, young, ambitious people a way to clearly have an impact in the world and do good. This is the exact feeling that large, prestigious organisations like Google, Goldman Sachs or McKinsey echo when they ask the very same people to come work for them. I’d have EA have its due too.

In the beginning it was perhaps important to find a small niche where they could quickly and legibly show impact. But EA is no longer small. It feels like it has billions in funding and tens of thousands of adherents, lots of whom are smart, powerful and engaged. This is too valuable to waste3.

I just wish EA didn’t stake out strong moral baileys in the form of dogmatic beliefs, philosophical underpinnings and ultimate aims, which turn out to be common sense mottes whenever they are poked or prodded.

Does it do good? Yes. Does it do the most good it can? No. Does its adherents argue incessantly about whether the way it does good is optimal? Oh god yes. Does everyone have multiple philosophical disagreements which ultimately don’t matter all that much but makes everyone feel like they have a voice? Seems that way. And no number of blogposts decrying the exact method of grant-making matters to this, since coarse grained large actions matter much much more than fine grained research.

We understand the future by creating it. Knightian uncertainty can't be solved by more analysis. It can only be met head on. It can perhaps be delayed by data gathering, but it always calls it's due.

Erik, in his fantastic critique of EA, called its fundamental morality of utilitarianism to be faulty, and said morality is not a market. In a nice bit of symmetry, I think he’s wrong. I think what EA needs is a market, if it wants to succeed in its aims.

If EA wants to be a priesthood focused on helping the poor and sick, that is an exceptionally laudable aim and should get accolades. It, however, is most definitely not the front lines of what it takes to help push humanity forward. Fighting against Knightian uncertainty by embracing ever more stringent codes of research is to retreat into Castalia, regardless of your adventures in the tail end of the probability curve. It’s akin to fighting entropy by embracing order. That way lies sterility, not flourishment.

The combination of belief in probabilistic legibility and increased belief in doing research combines in some of the longtermist work that EA espouses. For instance, a key problem is of following the trajectory re the x-risk, AI safety type work is that a large part of EA work becomes, in effect, a game of predictions. If the prize for guessing correctly is 10^6x, then you might end up dedicating large swathes of your efforts to the far wilds of the probability fields. And I fundamentally don’t think our methods of identifying the best low-probability-high-reward areas of explorations are anywhere near good enough.

Thus removing both the issue of having centralised authorities with limited precognitive abilities, the difficulties of dealing with illegible goods, and your own barometer of how important “doing good” is compared to your other motivators like “travel to see the Parthenon” or “buy a cool car”.

This is of course fine. No movement needs to answer all of our altruistic efforts. Its addressable market doesn’t need to be “all the good done in the world”. It might be the marginal path that tries for moonshots leaving the middle to the NGOs and governments or the mainstream path that solves the middle of the distribution while the ends remain free and require much more idiosyncratic intervention. (with all due apologies for the two dimensional characterisation). It can solve the areas that are better defined, the more utilitarian and prosaic analyses leading to malaria nets, and the slightly more complex ones of existential risk reduction through nuclear safety advocacy or bioweapons research bans.

A lot of the criticisms made about it are perfectionist fallacies. The criticisms compare EA to a Platonic ideal of a giving-focused organisation, and find the ways in which it falls short. Like I take it as granted that an organisation dedicated to doing X will oftentimes have difficulties with the fuzzy edges of X. I also take it as granted that some percentage of people, if they put their heart and soul into doing one thing and being a part of one organisation, might end up hitting a burnout wall.

But those aren’t inimical to EA the organisation. Most real world implementations fall short of perfection, often far short, but they still work. My feeling is that considering EAs want to do the most good they can, the way they’re looking at the world feels prone to self-defeat. Because they will see others achieve the grand goals they’ve set for themselves.

Thank you for writing this piece. It is hard to argue that GDP growth and economic growth are the surest ways to reduce "suffering" in the mid-term, 100% agree.

Have you come across any explanation for the seemingly reduction of self-reported happiness in the countries that are currently experiencing the most growth? I did an analysis recently comparing GDP per capita vs HDI vs Happiness over the past 10 years and am having trouble making sense of what it means.

https://www.notion.so/henriquecruz/Happiness-Report-75cda1301f244aa9807d1767f8ac29a4

some thoughts on the post (from a 'recently came across EA and have been reading on it' person):

1. diversification of world view is needed among EA orgs as noted by Holden Karnofsky (openphilanthropy.org/research/worldview-diversification). charity recommendations are great for people donating small amounts. they would not spend time for researching better ways and just want to see money well spent. but there should be more diversity of projects for people donating large sums.

2. EA provides framework for how to pitch for funding NGOs. and creates the culture of analysis of impact and tractability. the same must be true for startups pitching to investors by showcasing market demand and possibility.

3. a lot of EA policies is finding the best way, with small amounts of capital. I think as it increases, orgs with the EA philosophy will donate to more risky ventures that can result in much higher returns