Hierarchical growth trade-offs

How size brings complexity and creates barriers to change, and the impact of an ever increasing and invisible coordination tax

I

The Ancient Greeks figured out a decent way of managing their city states around the 5th century BC. They figured out that if they got people (non slave, non foreigner, non female, but .. you know ... people) to voice their support for ideas, it would act as a sort of collective glue cementing their pre-commitment to certain courses of action. In a surprising lack of inventiveness, they called in democracy, which meant people-rule. It worked pretty well, long as the sizes of the city states didn't get too crazy, around the 30,000 to 50,000 mark.

This by itself isn't particularly revolutionary of course, since tribes of all sorts are famously egalitarian, and there were forms of primitive democracy seen here. It only makes sense that some of the varied evolutions of this particular phenomenon, when transplanted into larger cities, would also keep institutions that are broadly similar in ethos.

And it's not just in Greece, but we can see examples in pre-Babylonian Mesopotamia or in Ancient India. So the logical evolution of the particular type of government, or organisational principle, seems to be one that has come about in at least a few convergent evolutions.

What is interesting is that as the sizes of the polities being governed kept increasing, the types of governments kept evolving. At some point it got inevitable that you needed mandarins and governors and tax collectors and supervising officials and representatives for various interest groups so that something vaguely resembling the will of the people got done.

Similarly, in business, at the very early stages, perhaps there is more direct information transmission amongst all parts of the system. Everyone is involved in everything from building to selling to customer feedback to office cleaning. But pretty soon, as it grows up and increases in size, you need to create some specialisation. Someone who knows a heck of a lot about Marketing does this. Someone who knows a heck of a lot about Engineering does that. And so on. And once it hits a ceiling of complexity, then you try and whittle it down again.

At McKinsey we used to do a bunch of work with companies that needed to redefine their "spans and layers", to reduce the number of layers between the decision makers and the execution folks, with the idea that the shorter the distance and lesser the middle managers, the more they could actually become agile.

While people have tried other organisational principles like better decentralised governance called Holacracy, it's probably fair to say they haven't really caught on. Ultimately, if you really want to get things done, which seems like kind of the whole point in most businesses despite what its seems, some hierarchical decision making seems necessary.

But these are systems that are designed by us, so perhaps there is something inherent in our human thought processes that makes the emergence of these structures inevitable.

In biology, things seem squishier, but otherwise pretty similar. Almost everything you look at that is slightly more complex than cytoplasm, there are an incredible number of highly complex machinery that interact with each other in even more complex ways. In fact even in cytoplasm, there are intricate arrangements of organelles (called so because they're like little organs), little tiny fibers, which perform specialised roles in the cell.

We could look at any other field in the world, and similar observations would emerge.

Hierarchies are everywhere. In all the most complex systems that we see around the world, hierarchies are present and highly visible. They seem an inherent part of any complex world. If there are systems which have a large number of inter-related component parts which interact in complicated ways, predicting the outcome is generally mathematically intractable.

The space also showed that whether it is self-organised like in biology, or manmade, like in governments or businesses, or a combination like with the entire economy where parts are manmade businesses, parts are self-organised in terms of the types of businesses, and parts are manmade to organise the self-organised parts like the regulatory state, hierarchies emerge everywhere still.

You can argue whether this is in fact new, or a subset of the pre-existing nonlinear dynamical systems study, but regardless there was an entire academic discipline that emerged in the 70s and 80s that tries to grapple with the overarching phenomenon of complexity. Santa Fe Institute, established in 1984, is one such that is dedicated to the study of complex adaptive systems, and was founded largely by a number of interdisciplinary researchers who were scientists with the Los Alamos National Lab.

Seems like it's everywhere from organism evolution to the organisation of Google, but why?

II

Let's imagine a complex system that is built up of, say, 100,000 components. A large, complex, network with 100k nodes and a large number of edges connecting them.

Let's assume that the "no hierarchy" network is connected together randomly, with each node on average connected to at least another one. And let's say the hierarchy-laden network has 5 levels, arranged in a typical pyramidal structure, just to make our analysis easier.

One assumption is of course that the stable mini-configurations are themselves relatively stable, so that they can each withstand certain level of perturbations without critical system-wide malfunctions.

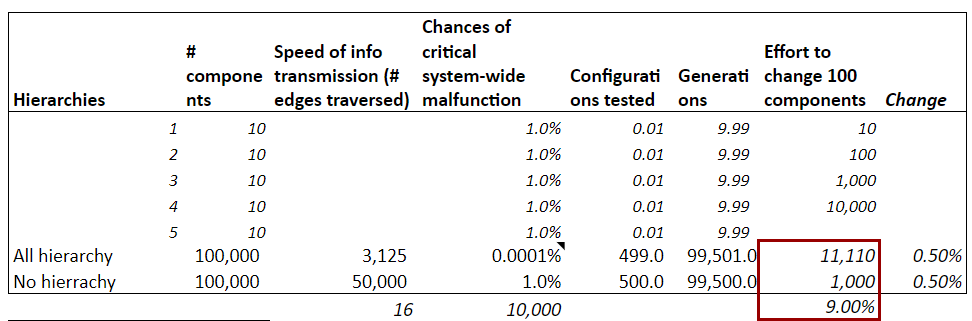

Within the network there's a mutation rate, the thing that actually brings about change to the individual components of the overall system whether due to random chance or trial and error in decision making. I set out to find how they all interact with each other. And the quick and dirty analysis here throws up some pretty interesting findings.

The interesting findings emerging from the analysis:

Hierarchies mutate faster, though very very slightly higher, to the tune of 1 extra generation amongst 100k. But it adds up!

Hierarchical arrangements perform global search and optimisation faster, with vastly faster information transmission speeds - 16x faster within the tiny stylised model (2^4), which grows dramatically depending on how many more levels are added!

Hierarchies are less fragile - The chances of a critical system-wide malfunction is around 10,000x lower with a hierarchical system of 5 levels vs a non-hierarchical random arrangement

Hierarchy necessitates modularisation - I don't know if this is somehow tautological, since almost by definition hierarchy requires some specialisation and separation, which requires that there be emergent modules that do specified tasks

The whole point of doing the exercise is not fidelity to reality, because anything on Google sheets gives up that pretence pretty quickly! But looking at even a toy model with a couple of moving parts can show us how readily the advantages to a particular arrangement can be seen.

But, the niggling doubt remains. Is this actually right? When I went and tried to read the literature I remembered one of the papers from a hero, Herbert Simon, that looked at the architecture of complexity.

The argument goes as follows:

Suppose the probability that an interruption will occur while a part is being added to an incomplete assembly is p. Then the probability that Tempus can complete a watch he has started without interruption is (1-p)^1000 a very small number unless p is .001 or less. Each interruption will cost, on the average, the time to assemble l/p parts (the expected number assembled before interruption). On the other hand, Hora has to complete one hundred eleven sub-assemblies of ten parts each. The probability that he will not be interrupted while completing any one of these is (1-p)^10, and each interruption will cost only about the time required to assemble five parts. Now if p is about .01 ... it will take Tempus, on the average, about four thousand times as long to assemble a watch as Hora.

Suppose that the task is to open a safe whose lock has ten dials, each with one hundred possible settings, numbered from 0 to 99. How long will it take to open the safe by a blind trial-and-error search for the correct setting? Since there are 10010 possible settings, we may expect to examine about one-half of these, on the average, before finding the correct one-that is, fifty billion billion settings. Suppose, however, that the safe is defective, so that a click can be heard when any one dial is turned to the correct setting. Now each dial can be adjusted independently, and does not need to be touched again while the others are being set. The total number of settings that has to he tried is only 10 X 50, or five hundred. The task of opening the safe has been altered, by the cues the clicks provide, from a practically impossible one to a trivial one.

The eponymously titled paper walks through a similar, though more elegantly stated, example that shows similar divergence both in terms of "search space" and resilience.

So this had been a paean to the benefits of hierarchies and how they benefit everything and everyone. Yet that doesn't seem to be the globally popular opinion. In fact the reason I got interested in this space is because in the entrepreneurial world one of the biggest shibboleths is that they are nimble and agile and run flat, tight ships, while the old guard are hierarchical and slow and all around plain boring. What gives?

III

Most of the arguments against the concept seem to be somewhat anecdotal, like most of management literature.

But if you look at the effort to wilfully change configuration, turns out a hierarchical structure has a high cost. The word wilfully is important here, as that assumes an end state that can be visualised and aimed towards. Let's try elucidate with an example.

Let's say you're JPMorgan Chase, and you now want to build the functionalities and general awesomeness that they see in Apple Pay. So far, so good. Shouldn't be that hard, after all you do already spend $4Bn on technology every year. How hard can building this be? So you set out on the journey. But to do that you need to get all your departments to play ball. Fine, as the CEO, you just decree that this be done.

But that doesn't seem to be enough. Marketing teams carve out time to work on it. So do the technology teams. Some are tasked with plugging in the new tech ever so carefully with the existing systems so that they don't shut down. After all, you can't destroy the existing bank in the hope of creating a new bank.

So then you say no problem. We'll just create a separate core team inside the big organisation who have all the powers of the larger organisation to draw upon. Budgets and talent readily available, relatively freely, as is customer know-how. But to make sure that what they're doing doesn't muck up other parts of the bank, there of course needs to be a few people. To coordinate, that's all. And the cycle continues.

Yes there are of course problems of incentive alignment. Heading a project generally isn't seen as a route to become a billionaire. But this argument seems surprisingly toothless once you dig into it. Most startup founders who get richer than god all seem to agree that they didn't do it to get rich.

Even being cynical I tend to believe them. Would you choose a job with a huge percentage chance of failure (>90% according to most research) if you had an investment banking option where you were pretty much guaranteed seven figure income? The most you can say is that they play the odds. Build something interesting in the hopes that it turns out to be good is a pretty good strategy, with relatively unbounded upside even if the downside is also large. If you're 25, seems a pretty safe bet. Worst case you'll learn something and go get a great job at Google.

Also, getting a phenomenal corporate salary, with job security, and a blank cheque to try build something awesome, sounds pretty cool! People don't build cool things only because they get equity. If that was the case 90% of corporate innovation would never happen. Not to mention that succeeding in one of these things is a great way to become the CEO themselves. In fact, an HBR study showed that most CEOs take risks exactly like this to get to the top job.

So it seems that the problem is something slightly deeper than just incentive misalignment. I think that it's rather that the hidden coordination tax eventually catches up to you. The benefit of being small is of course that you only need to focus on doing one thing. When you're bigger, your task is much harder. There needs to be an order of magnitude (or more) coordination efforts to predict the effects of any effort and to successfully popularise it with all the relevant nodes.

If we look at the crude model of interaction we'd built to hone our intuitions, it seems to be playing out exactly this way, with a hierarchical information gathering model requiring an order of magnitude more coordination compared to the non-hierarchical version.

So any effort at a large enough dissemination of information and coordination atop that pumps the brakes quickly enough that it acts nicely as a barrier to speedy evolution. And that stops the organisation from being able to respond fast enough to environmental changes or build innovation internally.

Can this be changed? Yes of course. It's neither inevitable nor a law of nature. If the change that needs to be built is already in line with what the organisation is already set up to do, the coordination tax drops dramatically. You're then dealing with a super-tanker moving forward with all the speed and momentum it's built up over the years.

Is this peculiar to the weird world of companies? Doesn't seem like it. Politics is way more ossified since it doesn't have the momentum of the profit motive to keep things dynamic. Science, or the practice of science? Despite the craziness that makes it one of the weirder collaborative places to work, or perhaps because of it, there's some potential here.

The forward momentum is provided by the drive that everyone wants to be seen as the Von Neumann of the age. The institution of science makes it bloody hard to do much through crappy mentorship, horrendous treatment of juniors and even worse pay. But the individual drive seems to have been a decent counterbalance to that effect. But now that a large part of science is experimental and collaborative, it sure seems like it's headed in the same direction as business and politics.

When you look at this all together it argues one of two things, albeit in different ways:

Hierarchy reduces the speed of information processing: It takes far longer for information to penetrate from the end of an organisation to the decision makers. The more hierarchical levels in between the front lines and the CEO, the longer it takes for information to percolate up.

Hierarchy reduces the ability to change course quickly: In a company with multiple sub-systems underneath, to change things requires an understanding of each individual system, and how they interact with each other. Without multiple subsystems, you could just tell the relevant nodes to change their behaviour, and off you go! But with the subsystems, you have to make sure that none of the changes you're actually telling them to do will actually destroy that particular subsystem, which means that the operational complexity of a hierarchical system increases in response to the number of layers.

Assuming the resources you'd need to get to change course is somewhat randomly distributed across the business, you need to look at the entire business to make sure that things work.

For example, think about starting a new business within a large company. You'd need to get some version of buy-in from marketing, sales, product development, technology, and so on and on. And it's not like they don't have much work to do already.

This is also the reason why companies occasionally create skunkworks to get things done, to remove themselves from internal bureaucracy. Despite it rarely working out very well, since something built under the clear intent of it being a moonshot project without the firming guidance of market feedback ends up being a hybrid that gets selected against.

It's probably fair to say that hierarchies in complex systems, like most things in life, have some drawbacks. Nothing is without cost.

IV

So what?

For one thing, it's important to see the hierarchy led ossification as a feature of the system, rather than a bug in incentive creation or alignment, or just the talent being somehow subpar, or some other equally pernicious arguments which can all be dismissed with even a cursory examination of the actual world we live in.

For another, it shows that our actions that focus on innovation often treat the symptoms and not the disease. Amazon is a genius juggernaut that can destroy industries by looking at them, like a corporate Medusa, and makes competitors shake in their boots through their incredible execution and insane talent. They also brought out the Kindle Fire tablet and a phone that sank so quickly it didn't even create any ripples!

What they've done is not showcase genius. What they've done is institutionalise experimentation. So that when they need to try something new, unlike JPMorgan above, they don't face nearly as high a coordination tax. Trying stuff out is not disruptive to the work, that is the work. But just so it’s clear, there are still taxes to pay. They're just smaller than some other companies at the same size.

In many cases, or rather in most, hierarchies aren't just straightforward pyramidic constructions that have clearly specified spans and layers either. Most of them loop back on themselves, creating more complex loops that link, say, the Levels 3 with 5. One happy outcome is that the coordination tax gets smaller the more interlinked they are. Which makes sense since the natural end point of this heavy interlinkage is to get back to the fully interconnected graph that puts the costs in the equation in the first place.

The way to deal with the costs of hierarchies isn't to wish they'd disappear - Chesterton's fence would crumple itself up into kindling if that were true. But to make navigating the hierarchy part of the job, and internalise the costs of that navigation far before you see fruits from it.

With data being sparse inside the companies, let's look at an anecdote, risky as that is. Caveat emptor and all that. The story comes from one of my friends who struggled with this. A large utility company which had a de facto monopoly on most of their consumers wanted to build something new and innovative. It's not a crazy idea by any stretch of imagination, since they did have strong assets. They had a large and diverse customer base that they interacted with on a monthly basis. And who were overwhelmingly at least neutral, if not positive, on the company and the brand.

As the obvious next step to do this, they hired a large consulting firm, where my friend worked, to try and figure out what they could do. The problem was, all of the digitally forward customer-facing highly successful venture capital backed companies, who got almost all of the press adulation, accolades, and market power, they seemed hard to catch up to without hundreds of millions invested in the project. You could just create an e-commerce storefront and see what happened (a real suggestion from the client) but even doing that somehow turned out to be much more difficult inside the company than outside the company.

So what do you do? You could deploy a few hundred million in trying something new, but even for larger companies it's a meaningful amount of money. And the chances of success, well, for that you can look again at VCs crowing about owning the power law distribution while the entrepreneurs cry about the stupid unfair winner-take-all world.

When I have talked to large corporates about innovation platforms, they have all faced exactly the same struggle. In fact it's one of the reasons why they end up investing into companies directly, in the hope of learning something from them. The problem comes about because of the hierarchy. Since nobody is clearly incentivised to make the project succeed, it often fails. But that's not just it. In fact if that were the only problem, they could throw some of their huge cash pile reserves at the person. The problem in this case is start they have to be able to suffer failure at multiple levels of the company.

The CEO has to explain to the shareholders that a risky bet didn't pan out, but weirdly enough this isn't that problematic by itself. Seems to happen all the time! But he (and statistically speaking it's a he) has to not just explain that a bet didn't pan out, but that he made it in the first place. Why did he think this was his job? Does he not have enough on his plate from running the company in the first place, rather than make random risky bets? The "random" part of the sentence being the most cruel.

The CFO meanwhile also has to be comfortable writing off 100 million for an idea which is risky, and do so in a manner that doesn't impact her job performance. The marketing team has to be comfortable writing off a year and a half of work, while delivering on their other pieces of work. The design team has to be comfortable trying to out do the small and nimble start-ups, while also keeping the existing machine in motion. At the end of the day the interfaces don't change enough, so the coordination tax just keeps adding up!

And every single employee who is interested in doing this bumps up against multiple walls of bureaucracy from Legal (are you sure we’re allowed to do this?), marketing (how does this jive with our 1, 2 and 5 year branding campaigns?), sales (do we get paid for this?), finance (where do we even put the capital?), other admin (so we share all the costs within the HQ right? Or split it all up?), and more. Every promotion cycle this all comes to a head and nothing gets done, because the department that actually sold a bunch of stuff and met their targets naturally gets the perks.

But could they just set up a separate company to try it out? Yes of course! As long as they can have a separate office (with maybe a pirate flag), separate funding, and limited requirement to be part of an observation ring, it could work. But there's also the reason why in the outside world 90% of start-ups fail to consider. Building things is hard. Making it easier by putting resources against it doesn't necessarily make the power law flatter.

Recognising it is a good place to start figuring out how we can actually manage the flow, rather than opt for smaller pieces of cookie cutter wisdom. It's not that the wisdom is wrong, it's that it's misapplied and doesn't provide a solution. Like most things in life, this information overload that creates a trade-off is the limiting factor that makes innovation harder.

When we are complaining about how IBM sucks and can't innovate, or the government are unable to even get a basic website up and running, or the scientists can't even get the whole "AI will kill us all" phenomenon appropriately addressed, it's worth noticing that this is a feature of the system. "Just do it" might work for going for a run, but for anything more complex you have to contend with the invisible hand of coordination tax!

If we did want to get rid of it, have a non-hierarchical organisation that is somehow still able to handle complex tasks, we need to figure out a way to increase the bandwidth of information transmission and processing within an organisation. We’ve done it before. Our organisations today are much more complicated than equally sized companies and polities in the past. But theoretically possible doesn’t mean practically feasible. Just trying it will be helpful though, since every increase in our information transmission will only help increase the efficiency. That should be the goal.

Thanks Rohit, beautiful and deep insights that span across many disciplines.

Talking of hierarchy and information overload, I would love to see more take-home points and summaries in your production. I tend to read substack when I want to rest my brain, I think many are like me, so the easier the read, and the easier the packaging of information, the more I can learn without effort.

This is an underrated article! I loved the mathematical formulation/simulation, it drove the point well. While the hierarchy here seems fixed over time, it can be an emergent & fluid outcome (viz in an organisation we see this in promotions & churn) and the process for this can significantly change parameters @ each level of the hierarchy.

an interesting aside - the flat organisation is much like a basic blockchain : long paths for info transmission & low prob of failure