How to play the glass bead game

Metaphors help us stitch ideas together and boost creativity; we should create them intentionally!

My favourite novel is the glass bead game. For the uninitiated, it’s a phenomenal book by Herman Hesse, who won the Nobel prize for it, that describes a fictional European village where extremely theoretical academics spend their time learning to play the glass bead game - which is a game that tries to demonstrate similarities between disparate fields like Chinese language, mathematics, gothic architecture and classical music.

To me the Game is a perfect metaphor for the extraordinarily wasteful focus of so many academics, in trying to play what is in essence a meaningless game to show each other how smart they are. But it’s also extraordinarily poignant in that this game, set in the service of the world, is an example of how innovation should, and ought to, happen.

It’s both an encapsulation of the benefits of learning, the possibility of innovation, and the futility of doing this purely at the theoretical realm.

Interesting things usually happen in unexpected intersections of branches of knowledge. Places where people haven’t quite looked enough, behind couch cushions and in between things. The best startups combine ideas lying around in unique Lego forms to better explore niches. The best scientific endeavours combine ideas, too—like Kekulé combining the artistic view of an ouroboros with chemical knowledge to come up with benzene’s molecular structure. Or when mRNA was suggested by Jacques Monod and Francois Jacob thinking in informational terms, later to be discovered at Caltech. Combining areas of knowledge can be uniquely helpful in breaking through stagnation!

I’m also doing my first salon with my friend Sam on connecting the idea dots, where you might find the inspiration for above. Come join us as we chat about how to connect ideas from multiple fields together!

We are almost never systematic about this, but rather are complacent, content to get occasionally surprised when such domain hopping turns out to be fruitful! This feels true despite the fact that metaphors and associations are how we learn almost everything, and how they’re the cornerstone of Eureka moments.

For me, as n = 1, I’ve always found the most excitement in using lessons from one domain to try hack another. One of my fondest memories of school was using techniques for working with infinities to solve a calculus problem.

If we're to push our technological and economic progress agenda forward we'll need to learn remixing ideas and do it far more than we are.

In ye olden days it might've been easier to do this, even be a polymath, because the depth of the fields were less and the number of fields weren't that many either.

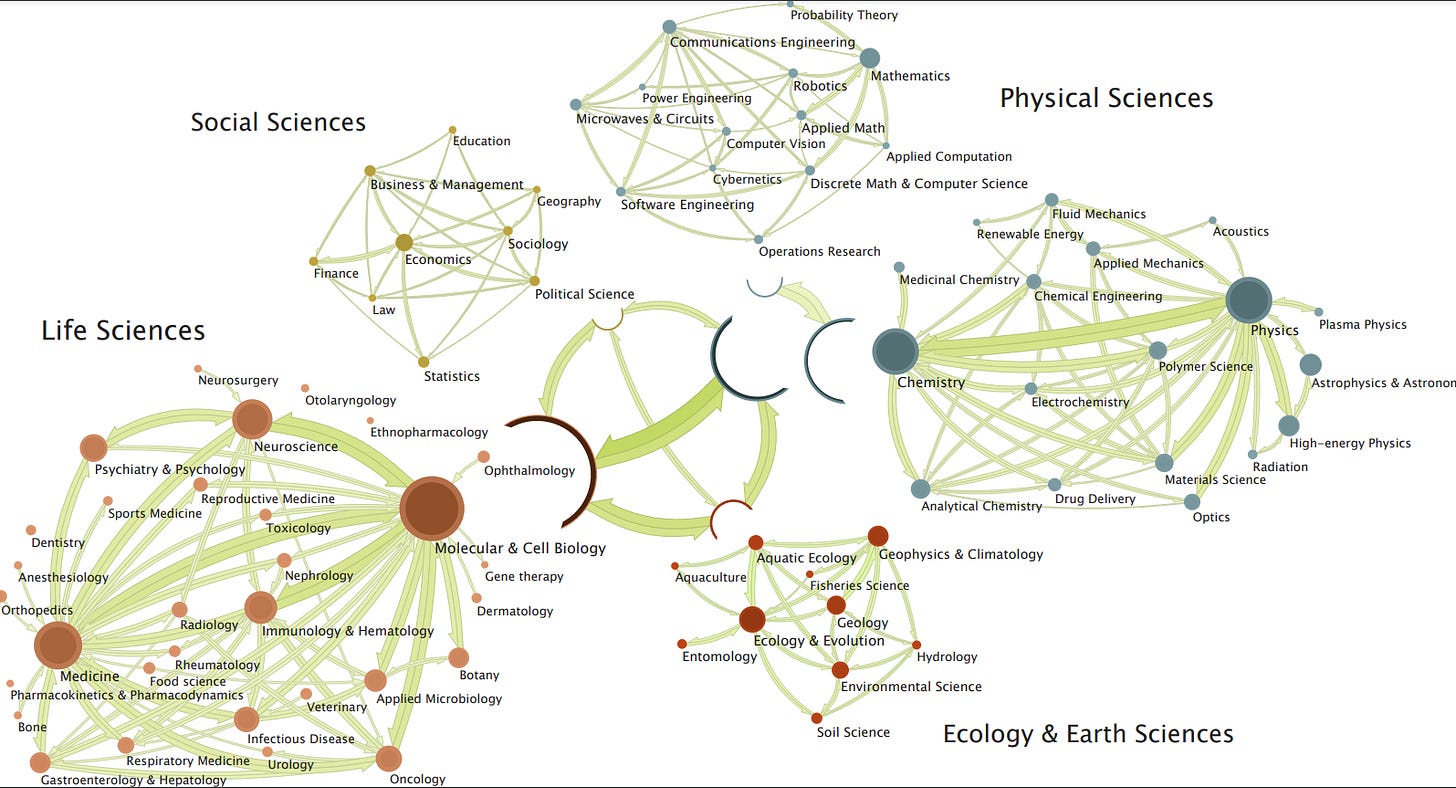

Look at how many fields of science there are today! Every scientist of note pretty much blanket states how their pan-domain exploration would be a barrier to academic tenure and career success. And the increase in the number and the specialisation that's demanded, for good and ill, makes cross fertilization of ideas much much harder. Even though when we do it we discover new heights.

How do individuals and firms explore such uncharted technological terrain? This paper extends research on knowledge networks and innovation to propose three main processes of knowledge creation that are more likely to result in discoveries that are distant from existing inventions: long search paths, scientific reasoning, and distant recombination

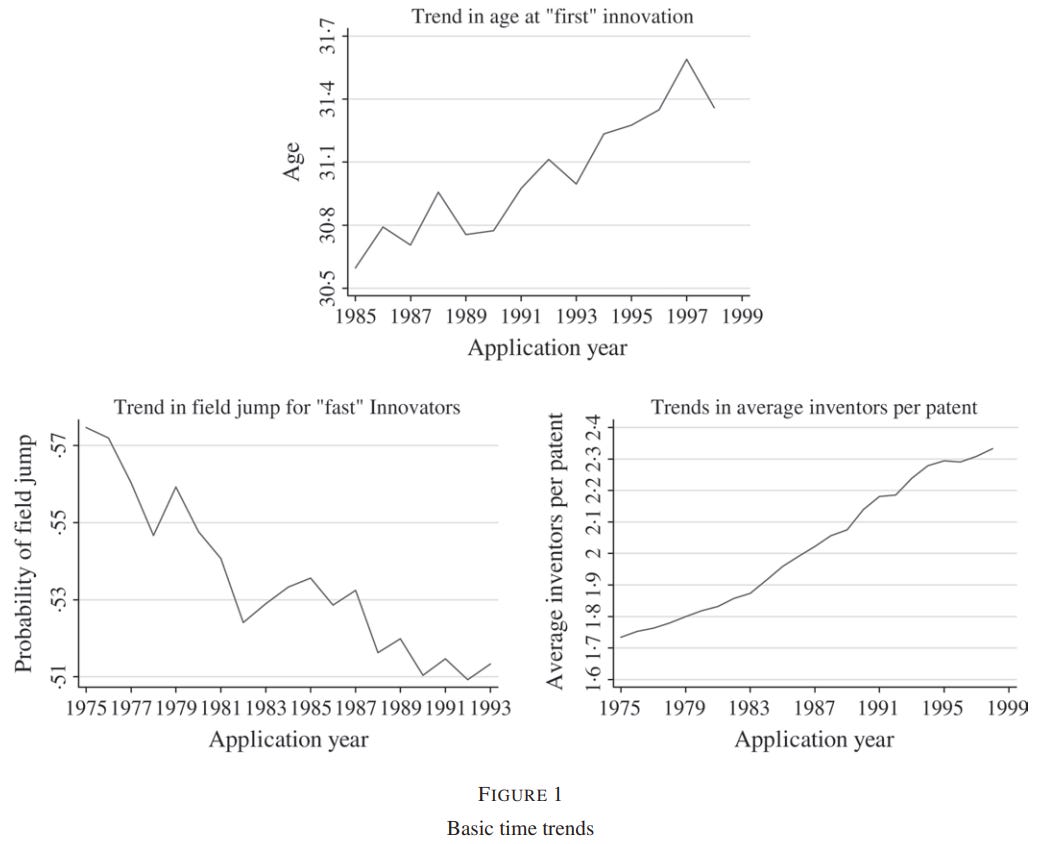

As Jones said in his 2009 paper, the trend towards increased specialisation and reduction in people moving across fields together paint a picture of increasing siloes and decreased mobility of insights jumping from one area to another.

The systematisation of this cross-domain learning isn't a trivial matter. Nor is this something that I think can be easily synthesised from existing knowledge bases.

In daily life, that’s how we discuss things. By analogy and by extrapolation. For instance, we talk about the evolution of a startup, of diffusion of ideas, of fitness landscapes, of cambrian explosion of ideas, these are all evocative because they link two sets of ideas together.

We call these metaphors. A figure of speech that links two things and “provides clarity or identify hidden similarities between two ideas”. Isn’t that what learning is? Using the tools and knowledge we have to try and make sense of knowledge we don’t have. To try and identify similarities between different ideas.

To learn easily is naturally pleasant to all people, and words signify something, so whatever words create knowledge in us are the pleasantest.

- Aristotle

The very metaphors we use to connect one idea to another are also pieces of a bigger game we play to build our creativity and boost our intelligence. It helps transfer chunks of knowledge without needing them to be atomised or reductionist.

And just like they are indispensable for learning, they are also the secret to innovation. Whether it’s the cross-domain spelunking that Jones above bemoans is decreasing, or the increased specialisation leading us to be siloed in our own narrow domains, its the absence of metaphors that trap us in singular existence.

And most of all, we treat it like a natural phenomenon that graces us with its presence or hits us like a lightning bolt, but rarely do we try and explicitly evoke its power to help learn, understand and explore new territory.

But needn’t be so, and it can be done.

For me the best explanation, being network minded as I am in my worldview, has been to look at the world through a naturalistic, ecological lens.

I've used ecological arguments to help understand the economy and financial markets before, to think about innovation1. This has helped me place some of the complexities of economics in context, or to help understand how investing is a function of who you are rather than what the best answer is.

So, here it is - The Glass Bead Game. The phenomenon I looked at here was complex systems, and the various theories it has within its boundaries, and the columns being areas where I wanted to see if there could be similar insights. They both might well be the shadows on a cave wall, but the rhyme here helps us in understanding them immensely.

I’ve had something like this table in my mind as part of my worldview for looking at and understanding the world for a long time. The boxes aren’t fully fleshed out. But they are already helpful for hypothesis forming. And they are helpful for insight generation.

Any attempt like this isn't going to be perfectly transposable equations from one to the other. You might use predator prey equations and get to better understanding inter-sector company competition, but probably aren’t going to be able to use the Lotka-Volterra equations to describe the competition within cloud infrastructure companies.

But even if you can’t copy paste equations, the contours being similar is enough. It means the thought processes that led you to understand one thing can be used, transplanted, finessed, moulded to help you understand something else.

This happens to be how we understand things and learn them. When we explain machines to children or gravity to high schoolers, we use metaphor to light the way towards a better understanding. They are the ladder we use to get better understanding of things before we throw them away.

Here’s another example I like; diffusion, spanning fields from economics to finance to physics to biology to AI.

These combinatorial intersections are also, frankly, the most fun places to play in, and where the most interesting insights come from. To imagine yourself standing on a beam of light with a stopwatch is to unleash very different ways of thinking about both light itself and the nature of creative inquiry.

So this is my challenge for all of you. Create your own game-boards from this and expand it. Choose something you're intrigued by and write out your thoughts and theories on the left, in the first column. Choose the questions you're grappling with, the sciences you want to explore, and write them as column headings. And see what the intersections bring about!

You won't be able to fill everything in, and that's okay. Indeed that’s expected! At least if you don’t want your extrapolations to get too tenuous. Figuring out where a particular simile finds its natural boundary can itself be enchanting. There's a peculiar organic beauty to this superstructure of how domains intersect. The bad side will be similar to the usage of quantum to suggest woo regarding your fate. But it needn't be thus.

You might also not quite reach the running-naked-in-the-streets Eureka moment (though if you do, y'know, share!) but you will understand better what you thought you already understood. Here is another template to spur those theories! Feel free to treat both X and Y axes as suggestions2.

Even with the most prosaic of problems, this is a fantastic tool for thinking and hypothesis generation. Like, say, you are trying to figure out the future of some bits of technology to see where you might look re investments. Which I did. And here the idea of niche separation and the unfortunate fate of most hybrid species helped me understand the API economy a bit better. The hyper-specialisation of software startups and resultant explosion in their individual APIs helped me understand the need for a better monitoring and orchestration layer, since coordination problems scale much faster than the addition of a new species, if the landscape isn’t highly mutable.

I think the best way to try and understand the power of systematising this that which we do so often, is to try and play with the idea that things might be self-similar.

The metaphors we use are how we learn, and helps us innovate. We should not let this happen solely by happenstance. Let’s go and make some more!

Here are a few of the times I've tried.

If you wouldn’t mind, please try as new tabs or new sheets please. I’d love to see the variations here!

I've recently started reading the Glass Bead Game. Many of the most universally applicable concepts I know come from physics, including entropy and the local minimums of energy being states of equilibrium. I will have to think about this for a while, Plinio.

I particularly like this because it is has weighty practical and philosophical implications, especially if you believe that there is an organizing principle, or set of principles, that underlie reality. To me, this looks like an attempt to approximate those principles. How else would such complex phenomenon appear so universally if not for them also appearing in the rules that govern reality? From there you can begin to use those principles and that toolkit to strip away jargon and get straight to the core of specific problems, pull from other domains for solutions, and synthesis across domains to innovate. Thank you for the intro to the Glass Bead Game!