Is The Government Efficient? (Adversarial Collaboration)

A debate on government efficiency and its limits

This is a new format I’m trying out for this week, a longform discussion. This one started with The Costs of Efficiency, which I’d written before. It sparked a debate which was particularly fun with Stephen Malina (whom you should all read by the way)! So Stephen and I decided on a longform chat to help clarify the question, identify our points of contention, and see if we could reach some sort of an agreement.

The core issue was that my article tried to look at empirical evidence of government inefficiency, and came up lacking. I’d set out to try and understand why the government is so inefficient, since that’s well-known to be true, and came away doubting the strident nature of the premise. Stephen, naturally, pushed back at this conclusion, both in terms of data and the assumptions, since logically governments have far less error-correcting mechanisms or incentives to be efficient.

That’s how we embarked on this discussion. But first, a trigger warning - there’s a rational discussion that ends in a reasonable conclusion, including a 2x2 at the end! Onwards: (Stephen’s the one in quotes, I’m outside.)

In his great post on government efficiency, Rohit starts to investigate the question of whether government is truly less efficient than private alternatives as standard wisdom assumes. One of Rohit’s main points is that when we look at studies that compare efficiency between private and public options in areas such as healthcare, the results tend to be a wash. Sometimes the government comes out more efficient, sometimes the private sector, with no clear trend. I’d be lying if I said this didn’t surprise me initially, but I do think this type of comparison ignores a key factor that affects the seeming lack of difference between public and private options in these areas. By virtue of the fact that these areas have comparable private and public options, they tend to be areas that are heavily regulated. If we instead look at areas in which the government provides an option but limited oversight for private competitors, we may find a different story.

Take, for example, (as mentioned in the comments) the US Postal Service vs. Fedex / Amazon / etc. The first is seemingly hamstrung by its micro-managing oversight from Congress while the latter are highly efficient, functional institutions. Perhaps this isn’t a fair comparison, though, as the postal service has to service areas these other options don’t. Instead, we can look at Germany’s postal service before and after privatization. As far as I can tell, Germany’s private postal service is meaningfully more efficient than the previous public version despite being required to provide service to the entire country. In other words, when we look at an area where private options aren’t severely restricted by regulation, we find a clearer efficiency difference between the public and private options. Obviously, proving this hypothesis conclusively would require more case studies, but the postal service example is suggestive that Rohit’s comparison is missing an important factor that impacts relative public vs. private efficiency.

Another argument against latent government efficiency is the one from common sense. Anyone who’s had extensive interaction with any of the IRS, school boards, public healthcare provision, or the DMV has probably not come away feeling served by an efficient, customer-friendly apparatus. On the other hand, while we can disagree over Amazon’s business ethics, most seem happy with their handling of delivery. Ironically, these four examples are cited in Rohit’s post as areas in which greater government investment can help us cash proverbial trillion dollars on the sidewalk. Given my (and I suspect your) strong priors against these organizations being paragons of efficiency, the claim that marginal investment in them will produce massive benefit warrants skepticism.

I think the claims of dissatisfaction with government services and the path to potentially greater efficiency (measured as higher outputs for a given input) is possibly true, and your examples are well taken. However, the trouble is that when you try to measure them, the differences tend to not be meaningful in either direction. The Post Office examples are intriguing. While there have been successful privatisations in Germany and Netherlands, there are significant local variables that make it tough to look at these as generalisable examples. In USPS for instance, the arguments for privatisation points to the inefficiency and losses as the reason to do it. The arguments against however note how we have hobbled USPS through pricing and operational rigidity.

The common sense argument is one that I have a lot of sympathy for. It’s also what I, personally, have felt. Which is exactly why the empirical argument is interesting. The reason for the NPS scores for government departments being so low can’t be just that they’re in the public sector. They seem to achieve a measure of success in a large number of arenas. None of this is to say that privatisation is always bad, because that’s clearly not the case. But the argument is that it’s no panacea either.

Private entities are of course able to form conglomerate structures and increase profitability through inorganic means or operational changes, which public entities are not allowed to do. While this increases the potential reward it also increases risk. I acknowledge they might not be commensurate. And while I’m fully sympathetic to the notion that private sector companies are run better, the goalposts are also often different. Public sector companies have goals of universal service provision for an acceptable price, whereas private sector companies have goals of profit maximisation while not falling afoul of regulations.

We tend, far too soon, to cast out anything government related as bad or inefficient, and it’s that kneejerk reaction that’s incorrect, since when you look deeper the level of inefficiencies often seem misjudged, miscalculated or overblown. I had started this to try and explain why the government was so inefficient, and ended becoming a bit of a statism apologist! I’ve become a lot more sympathetic to the types of rigidities that government departments play under and become far less sympathetic to the claims of private sector efficiency, without noting the specific circumstances in which they operate.

In the interest of finding a crux, how about we drill down into the postal delivery example a bit? My understanding was that privatization has been successful in Germany and the Netherlands despite the private entities continuing to offer universal services. Related to this, you say “we have hobbled USPS through pricing and operational rigidity” as though that’s totally separate from the public vs. privatization angle. In my mind, you have identified a proximate cause but failed to connect it to the root cause, that decision by committee tends to be the modus operandi of government-run organization (or at least a favorite hammer). I agree that if your model of a public organization is an almost entirely separate with wide bandwidth to innovate organizations like the Fed or DARPA, then this is not intrinsic. But in my mind, the Fed is an exception rather than the norm.

It’s a useful distinction to think of the causes that make an organisation unable to fulfil its goals. I think the difference lies in our levels of belief on how much of the govt is intrinsically incapable (as above). I think we also fundamentally underestimate how many things the govt actually does, and does well. Michael Lewis explored three departments - Energy, Agriculture and Commerce - in his book The Fifth Risk, and showed how vast, sprawling and incredibly important various parts of government are. Not just in spending billions or employing millions, but in looking at the thousands of niches where there are no markets, currently or conceivably.

That’s partially why it seems our base “public inefficiency vs private efficiency” mantra is mistaken. We have empirical evidence that the efficiency levels are roughly equal (in the developed world) and we have plenty of anecdotal examples that prove all sides (govt inefficiency, private sector inefficiency and the opposites). The case of USPS that you brought up, for instance, isn’t a case of government inefficiency as much as a case of intentionally broken organisation. From an EPI article: “USPS is mandated to be self-financing, but has limited ability to raise prices, cut services that do not generate sufficient revenue to cover costs, or expand into more profitable areas.” They also have to fund their retiree health benefits for 75 years into the future (around $5-6 billion a year). These are not operational mis-practices or inefficiencies, but intentional laws.

With specific policies in place, we can hobble any institution, public or private. For me, what has changed are my priors in terms of the efficiency of a department depending on the ownership of who’s running it. Decisions by committee does tend to suck, but my contention is that this doesn’t seem to be special to a particular mode of ownership.

Yeah so I feel like we are converging in the sense of fully resolving the remaining aspect of our disagreement would require a very detailed study of efficiency across governments and businesses with significant attention paid to different departments, which we’re not willing to do (I assume). In lieu of that, I wonder if there are any predictions we can make which would 1) highlight our remaining disagreement and 2) provide a way for one of us to update when/if we’re wrong.

The difficulty in measurements means this is very hard to answer empirically, as I’d originally set out to do. But I’m beginning to get a sense that the meta-question is what remains unanswered. For any instance of industry with different ownership structures, the efficiencies seem roughly in line. However it’s in those instances where you need directed innovation that the ownership structures seem to diverge somewhat.

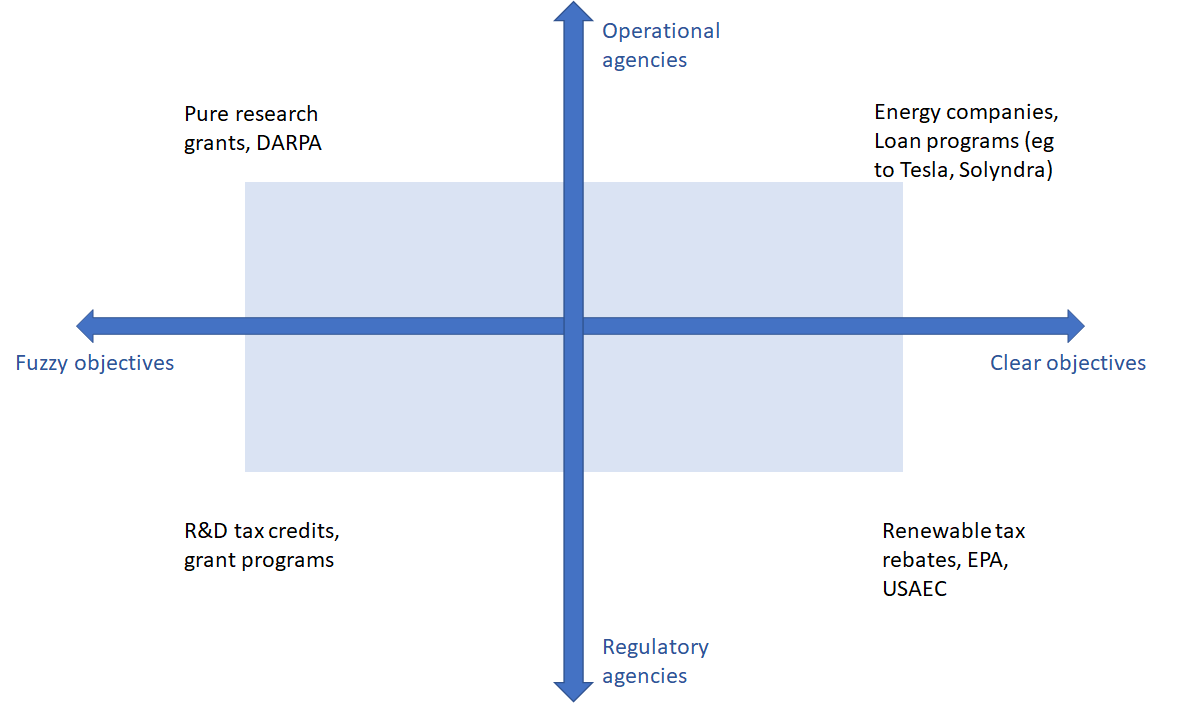

So while we might get equally effective setups in both at a point in time, one has the edge in pushing the envelope of further efficiency increases. The conclusion I'm reaching is that the governmental efforts have a barbell distribution - at the very early stages when even the ambitions are diffuse,the government remains a great way to redirect large resources to enable others to pursue fuzzy objectives. At the late stage where the objective is relatively well established, govt again remains a reasonably effective way of providing a service.

But there remains a chasm in the middle - areas where the private sector, sufficiently motivated by competition and sufficiently regulated to prevent negative externalities, ends up being a better alternative. After all, there’s a reason we don’t have governmental supply of toothpastes and bottled water! And a reason why NASA’s biggest success since the moon landing came when they chose different procurement procedures and new entrants figured out the way to innovate.

So now, a few predictions/ conclusions:

Overall, for the fuzzy ends like science funding or basic research will mostly be pushed through govt programs, which will be superior in both quality and quantity. And like in VC, you won’t be able to tell if a portfolio is good or bad for years, and one breakthrough might redeem an entire crop.

The more concrete sectors with clear success criteria will require the government to play a strong operational role to get full cost effective coverage, including utilities, healthcare, infrastructure or education.

The ones in the middle, where innovation needs to be unlocked, the government will do better when it’s more “enabling” rather than operational.

I agree with these. Here’s a weak attempt at some more concrete, crux-y predictions:

NASA’s SLS vehicle won’t have a successful mission.

Conditional on the USPS getting privatized, it becomes more cost effective without degrading service. Conditional on it not, it (subjectively) continues to be considered inefficient.

Were we to categorize government agencies by “level of independence”, we’d find that more independent agencies tend to be (on average) more efficient.

SpaceX’s Starlink program will provide cheaper internet with roughly the same coverage as the government-supported alternative.

The entire reason I started this blog was to chat with smart people and hopefully learn something, so this was clearly a win! Here are two things I changed my mind on as a result of the chat.

The first one is that our current debate on efficiency itself sometimes confuses the actual problem. It’s not just government services aren’t delivered optimally, it’s also that sometimes government services, because of the way it’s set up, lead to ridiculous outcomes and twisted incentives.

For instance, let’s take the most recent SNAFU in the US (though it also happened in the EU) where the regulators stopped J&J vaccine from being administered due to a 1 in a million chance of a rare blood clot. From the outside, even if the rate was much higher this was clearly a nonsensical decision with only downside. But looked at from the inside, you could argue the FDA was trying to credibly build and create confidence precisely because they’re willing to let people die rather than delay an investigation. The callousness of the act is what will help us the next time FDA makes a decision, because we can effectively never again tell them that they haven’t done enough risk analysis. “Look, we killed a thousand people in a pandemic rather than take risks. You really wanna tell us we’re not doing enough?”

That’s an example of the government acting understandably but ridiculously. There are plenty of anecdotes like this, which is what makes the argument for government efficiency seem ridiculous.

But the key is that Governments have dual roles - as operators and as regulators. As operators they seem to be decent, nothing spectacular (unless you’re Singapore) and even reasonably efficient, as I’d looked at in the article. As regulators, they demonstrate wide variances in their abilities. Half of the angst we feel is re bad regulations ineffectively applied by organisations with twisted incentives! It’s the “computer says no” version writ large!

A second key thing this debate clarified for me is that there is a spectrum of roles that the government can possibly play in, which isn’t visible when we look at the areas where we have empirical evidence of government vs private sector efficiency. For instance, there’s no way to know if a video streaming service started by the government would be equally efficient, since there’s no reason they would try!

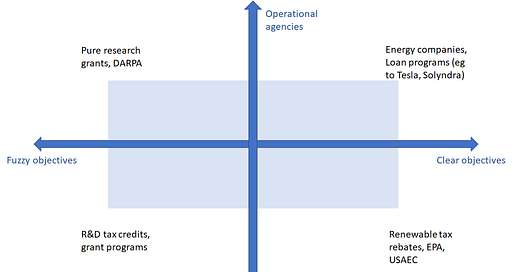

The spectrum goes from fuzzy objectives at one end (“we need more research on longevity”) to concrete utilities with clear objectives on the other end (“we need an energy grid”). At either end there is a clear role for the government to play, but the middle ground is where the government has to be an enabler rather than a player.

Together, this means that, if you were so inclined, you could create a 2x2 like this. At the center shaded part is where you’d want to hand off to the private sector, and at the extremes where we would rely more on the government.

(And to satisfy the audience, in case you wanted to see an example of idiocy in regulations, I present to you the European proposal for regulating Artificial Intelligence here.)

And also, from Stephen, on things that he changed his mind on:

This was also very helpful for me! I also changed my mind on several things.

First and most important, I realized that focusing on public vs. private is often not the most productive angle for examining organizational (dys)function. Instead, it's better to focus on which organizational structures provide the right incentives for solving different problems.

Second, I agree that drawing a distinction between regulation and operation is very useful!Third, I realized my thinking on this topic was being overly influenced by the availability heuristic and that if I want to have a more informed view, I'd need to spend more time doing a more comprehensive analysis of different areas.

Appendix: My initial breakdown of the problem was that Govt inefficiency is seen as much higher than what it plausibly is, because of a few possible reasons:

All the flaws are highly visible - one Solyndra makes news, even though the program was an unqualified success. By this metric every investor and lender are essentially horrendous

Their KPIs are different - Scott’s legibility point applies. Govt is trying to do diff things than just maximise output per input. This is by design in most cases, though maybe it shouldn’t be

Their size is different - having a much larger scale means there are way more hierarchies to work through, which creates natural inefficiencies re information transmission/ inertia in policies etc. But those aren’t unique to govt. In fact since we kind of need the govt (due to the first point where govt svcs are largely helpful/ net positive or neutral while usually covering more folks), these might be the cost of doing business?

Put all together, we should absolutely work on making the govt more technocratic in multiple places and make it work way better, but the rhetoric of “it’s inefficient” probably isn’t particularly instructive.

Public vs Private is actually less important than the competition vs monopoly dimension. Both Ontario and Alberta privatized DMV-type services. In Alberta anybody can start a registry, they get paid a processing fee for each service $10 say to to renew a license. In Ontario they contracted out the operation of the existing offices to one company (incidentally this company also runs a lot of private prisons). In Alberta you can renew your drivers license in 5 minutes and there is probably a registry within a 5 minute drive from your house. In Ontario, you're driving across town to the one location and it'll take you all day.

I haven't looked into it, but I'd bet private prisons aren't much better than public prisons. However, if you'd let anybody open a prison, let prisoners choose which prison they went to and paid these prisons a flat fee per prisoner, private prisons would guaranteed be better. Come to think of it, that might not be such a bad idea.

I'm not a big fan of empiricism in the "dismal science" precisely because the argument above can seem impossible to solve and economics till 20th century was not empirical even when it was possible to be empirical. If you think from first principles (praxeology) you should be able to resolve the problems quite easily. The best form of management is the "benevolent dictator" format which the entire corporate world runs on. You have a good leader who then hires subordinates, gives them responsibilities, who in turn hire more subordinates and so on. Leaders can listen to subordinates, or be a complete dictator but really that is just comparing management styles. Governmental Organisations however have a bureaucratic management style. Here there are nominal heads, who don't get to appoint most of their subordinates or fire them. Decisions are made not top down, but bottom up rule based. The lowest bureaucrat tries to decide on a certain rule, if there is ambiguity it goes up the food chain, to the end reaching the leader who is basically a guy that resolves ambiguity and sets precedent. If he's wrong, the courts of course can write the final law of the land. This problem also falls when the government tries to provide a service like the UPS. UPS is a rule run organisation, if the UPS wants to change it needs to change some rules that will be applied equally to the entire organisation. When the UPS encounters a problem, it solves it in a process based way. It checks the rule book, tries to find the process that it needs to follow given the problem and follows it to a T. It is an accountability free organisation, where if everyone follows their rules to a T, then everything is fine, no yearly targets, no goals nothing like that. Amazon is goal based, when it encounters a problem it empowers its employees to solve it, not solving it can get you demoted, transferred etc. Interestingly as corporations grow old and die they become increasingly process driven, (as you might have noticed if you worked in a large Fortune 500 corporate like IBM or ITC) and lesser and lesser goal based. It is less likely for a corporation to die by a leader choosing the wrong goals, more likely when the leader tries to avoid accountability to the board by setting up a process for everything. The market is useful in letting corporations die when they become sclerotic and paralysed, something government agencies do not have the fortune off. So this is the praxeological/ deductive argument based on the first principles, let us see what I can predict based on this:

NASA has become a process driven organisation and will never innovate compared to a company like Space X. NASA in its founding was in fact goal based and more like a corporate with lots of money and a non profit motive (goal was to reach the moon). To see evidence of this, there is the book "Apollo" by Charles Murray that shows the culture between early NASA and later NASA, with many of the early engineers lamenting what happened to it.

The fact that most of our modern inventions have become from DARPA does not surprise with the above argument. Defense is actually run command and control based and goal based, not rule based. DARPA also has deep pockets which is necessary to pursue risky ideas. To see this: you can check the culture of DARPA in this in depth article by Benjamin Reinhardt: https://benjaminreinhardt.com/wddw

DARPA actually goes above and beyond and follows the structure of some of the most innovative organisations in the world. This is described in the book "Dynamic Economics" - by Burton Klein, where he lists principles that he found in the most innovative organisations of its time, and its clear that DARPA follows most of them. This Blog Post: https://scottlocklin.wordpress.com/2021/02/17/planning-of-invention-part-1-burton-klein-and-dynamic-economics/ provides a useful overview in case you can't read the book.

Singapore of course provides excellent service because it is run in a command control goal based manner. It pays the highest salaries in a bad to attract the best talent and also empowers the employees. In fact it seems like the entire country of Singapore runs like a corporation and it is a democracy in name only. People have some voice but they can't openly criticise the government and they vote for the opposition to keep the ruling party on its toes).

Government money isn't inefficient, that doesn't make sense. So when the government just gives money to private organisations, its not bad if the organisations are run well. Government can this way fund a lot of innovation (this is very different from giving money to the NSF). Solyndra occurs but also Tesla and Space X occurs so giving money is fine, unless you choose an overly bureaucratic way of giving money.

I suppose the final conclusion is what can we do here to improve our government:

1- Retire all Government Employees (from most organisations). You can provide them good pensions, good severances but they need to go. A stage comes when a corporate has become so paralysed under it's weight that it kills innovation and requires an exceptionally incredible leader to turn it around. Markets fortunately automatically kill such corporations, governments are not subject to markets, so the government should kill it on its own. One should preferably do this at a regular time scale (say every 50 years?)

2- Recreate all the organisations that are necessary from scratch with new talent and a command and control structure. Hire good leaders and ensure they can lead the organisations for at least 10+ years. Changing the leadership every 5 years with a new presidency is a very bad idea, I also don't advocate for allowing the president to fire employees as that means every 5 years entire organisations can be diluted, which isn't great.

Im actually just recreating the conditions of the New Deal. They had a command and control structure, they had the best talent and were stable for around 12 years and even after that, the heads weren't changed all that regularly. I don't doubt the new new deal (or the green new deal) will again over time 70+ years, become incompetent sclerotic and inefficient. No modern corporation has lived long, the only corporation that lives long are family run businesses that are too small in scale to compare. The goals of the agencies recreated can be decided by the president, also I don't think this is politically possible and I think America is going to hell, but if theres a way out, we need a new FDR.