Meditations On Regulations: Quis Custodiet Ipsos Custodes

We should sunset more regulations and introduce an adversarial system to manage our sprawling regulatory state

Scott Alexander of ACX has now a series of three articles that look at the monstrosity that is FDA approval and criticises their ineffectiveness. They are characteristically great and everyone should read them. They also combine logos and rhetoric rather well, so you might just end up convinced too, depending on which side your sympathies lay before. I know I was.

But I remembered my epistemic learned helplessness of yore, and had a few questions that the essays didn't really get to. To whit.

Is FDA uniquely bad, or are we saying they're not that great compared to a more perfect version of an agency which might or might not exist? In other words, what's the base rate of badness we should start with?

Have they always been bad, or is there something more proximate that's made the drug company spend crazy $$$ trying to get through the wringer?

Why do the people who went through the process like and admire the FDA? Is this some weird Stockholm syndrome gone awry?

So I wanted to have a look at whether we could get an answer here. If you're sick of reading about the FDA (I won't blame you) do feel free to skip to Part III and IV where I flesh out some systemic solutions!

Tl;dr: Apart from nuts and bolts solutions, I call for an anti regulator who's incentivised by taking away rules and regulations, and I call for each regulation passed to have a sunset time (when it gets rolled back) unless it's proven to be actually valuable.

The failure of the FDA is the failure of scale

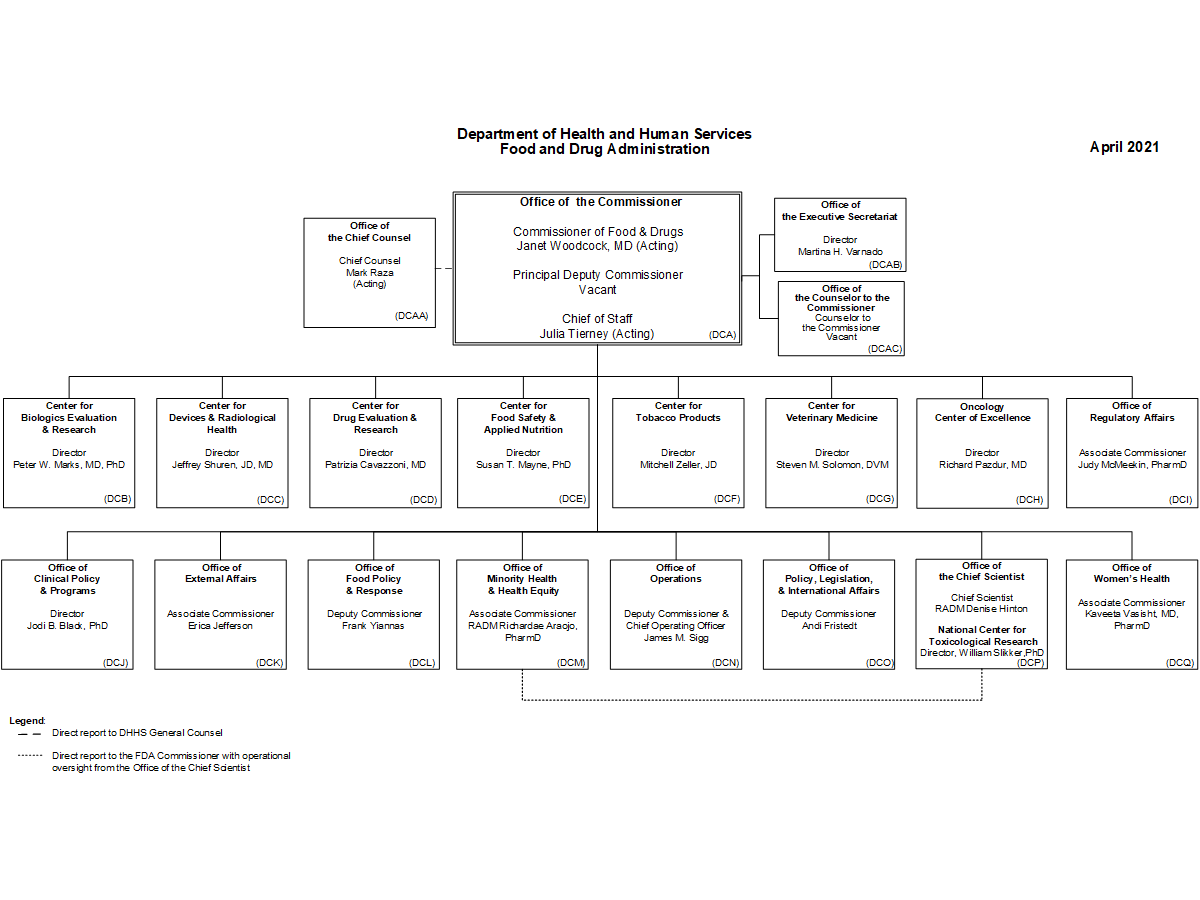

FDA, for what it's worth, has a budget of like $5Bn, of which $2-3B is paid by pharma companies, and with their 15k employees they oversee around $2.5 trillion worth of consumer goods. That's an insane amount of leverage, and they look after everything from medical devices to drugs to consumer products like sunscreen. It's ridiculously expansive, and it's gotten so because we keep finding new areas where we need guidance, and add it onto their list.

You can argue they're too complex, and in fact I believe that, and if you don't, just have a look at this org chart below. That poor Commissioner has 16 direct reports, each of whom also has similar sized organisations underneath. I can only imagine how many zooms that is!

Most regulatory organisations are much much larger than we naively think them to be. This is no reason to keep believing it's right for them to be large, but at least we can understand that the problem of cutting them down isn't so ... straightforward!

And in the FDA, their work goes on for thousands of products. And they still need to produce a certificate as one organisation. Somewhere there are multiple leadership teams meeting who report to other leadership teams who report to the top, all of whom are trying to figure out what decisions should be made this week.

And it's hard. Because if you have 10 projects ongoing and want to do a status update on all of them plus do review meetings, that's the week gone. Easily. Do this whole thing 10 times in parallel, and you could easily have an organisation of 1000s but where things take forever to move.

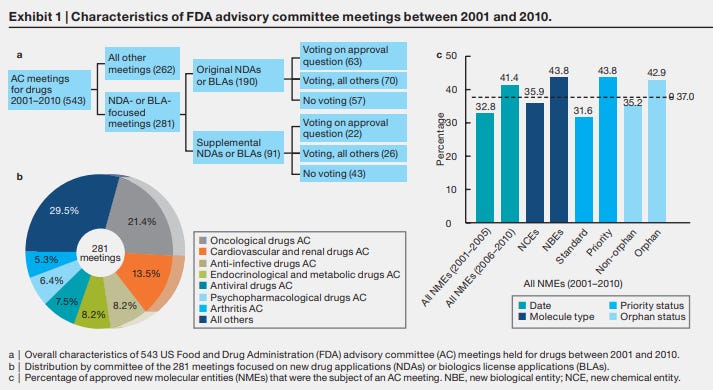

You only need a few to need an update or a signoff from one of the executive level teams to get into a time crunch situation. No matter what you do, there's only so much time! Here's a data backed view of what this might look like, and it's already 10 years old! But you can start to see how a meeting a week for 10 years just on the advisory front could be a possible problem for speed.

That's a hell of a lot of meetings. And it's not the whole thing, that's just the advisory committee ones.

FDA advisory committee meetings are high-stakes interactions, with many years of effort, millions of dollars of investment, potential regulatory approval, and billions of dollars in potential sales for a new drug riding on the outcome

The private sector tried to solve this by making people work harder. You wanna get richer? Well, work harder. Don't dilly dally but push everyone who works for you to move way faster than they'd want to. If they're slacking fire them and give the new folk an incentive to move.

And it works in some places. But even there you only need to look around to find private sector companies, replete with the profit motive, where almost nothing seems to get done! I'm not even talking about the IBM and Oracles of the world. Twitter is guilty of this (or was), LinkedIn is. And outside tech, phew, five year innovation budgets and transformation projects are the norm!

In the public sector this incentive is missing. Which is completely understandable. But it's important to realise that the speed with FDA moved is comparable to literally any private sector company except for the startups. The only massive companies who move at that speed are maybe Stripe, or Coinbase, and they're also not that old. Neither are they nearly that complex!

So in thinking that FDA is too sclerotic to be effective, the argument being put forth is not nearly specific enough. It's kind of true of almost all large organisations - public, private or otherwise. Your base credence should be that they'll be pretty sclerotic and/or bureaucratic anyway.

Also, it's not just the FDA, regulatory headache is literally everywhere - for instance the banking sector promotes the enormous pain in the ass that's getting a banking charter in the US. Same for FAA, making anything other than a paper kite fly will get you mired in paperwork until you promise to only travel by Amtrak! Same for SEC, after all, everything is a security.

All organisations that do well generally, but through risk averseness and general bureaucratic ossification make the lives of those who have to deal with them hell.

In fact, that's the problem. That's what the rah rah blogosphere misses. Because if everyone's the same, then the ire at "slow moving useless organisation" becomes ire at most organisations which isn't helpful.

If FDA the organisation is being highly effective within its confines, that's a problem for the FDA sucks argument. Because what you are actually comparing against is a mythical public sector that moves as fast and nimbly as startups. And even the private sector profit motivated simple lines of business companies haven't been able to do that! (Apart from Singapore of course)

In fact when you read the incredible frustrations that make up someone who wants to do anything re flying machines, or someone who wants to work on nuclear power, or someone who wants to just pretty please start a bank, FDA comes out looking rather well.

So when we talk about why isn't the FDA doing everything in their power to speed up the vaccine approvals or recall sunscreens, we're asking the same type of headline that asks "Why didn't Microsoft handle the transition to mobile better", or "Why did Google waste so much time and money with Google Plus?" or "Why is Facebook spending billions on metaverse?". It's comparing an actual, physical, organisation against a fictional, perfect counterpart.

These are great questions, but the meta point is that every large organisation seems to go through this phase. They get large enough to need a whole bunch of layers to actually do their work, and as a consequence they get ossified. And then you try to chip away and thin it down and work like crazy to make sure it's relatively efficient.

Part of it is the fact that decision making is hard to shift in a centralised business structure. Part of it is that when you have a smaller number of decision makers and a larger number of doers, almost inevitably you get into information bottlenecks, but that's an essay for another time.

Ultimately the key is, even in these private companies, the decision making hierarchy is a hierarchy, with a CEO at the top. They can try to learn enough to devolve decision making authority down, but information percolation has a cost. And that cost is the processing time at each layer before decisions can be made.

In order to speed things up you might mandate certain activities across the board - that's what standardisation does - but that very mandate is what creates the inflexibility of the "computer says no" variety.

A billion here, a billion there, it starts to add up

During my time at McKinsey, I used to try and stay away from two of the seven floors in the office. One was financial services and one was pharma. Both seemed like places where you'd go to get your soul sucked out of your eyes. But while financial services people, several of whom are close friends, exhibited a sort of deadeyed joy in their work, the pharma people were unfailingly, excruciatingly, happy. As far as I know all of that was innate and not at all influenced by their clients.

One of the problems with working there was that you'd get asked to solve problems for their clients like "I'm spending billions in my R&D every year and I have diddly squat to show for it".

In general its one of the big charges levelled against the FDA, that it costs $1 Billion to get a drug through the pipeline.

The study estimated that the median cost of bringing a new drug to market was $985 million, and the average cost was $1.3 billion. This is in stark contrast to previous studies, which have placed the average cost of drug development as high as $2.8 billion.

But this figure seems false to me. It includes all the failed drugs that didn't get through the pipeline.

Imagine the same principle applied to venture capital. It would be like VC firms adding all the money invested in every startup that didn't become Facebook in assessing their true "cost" of the investment in Facebook. Which makes sense from the drugmakers' perspective, but definitely doesn't make sense when looked at from outside!

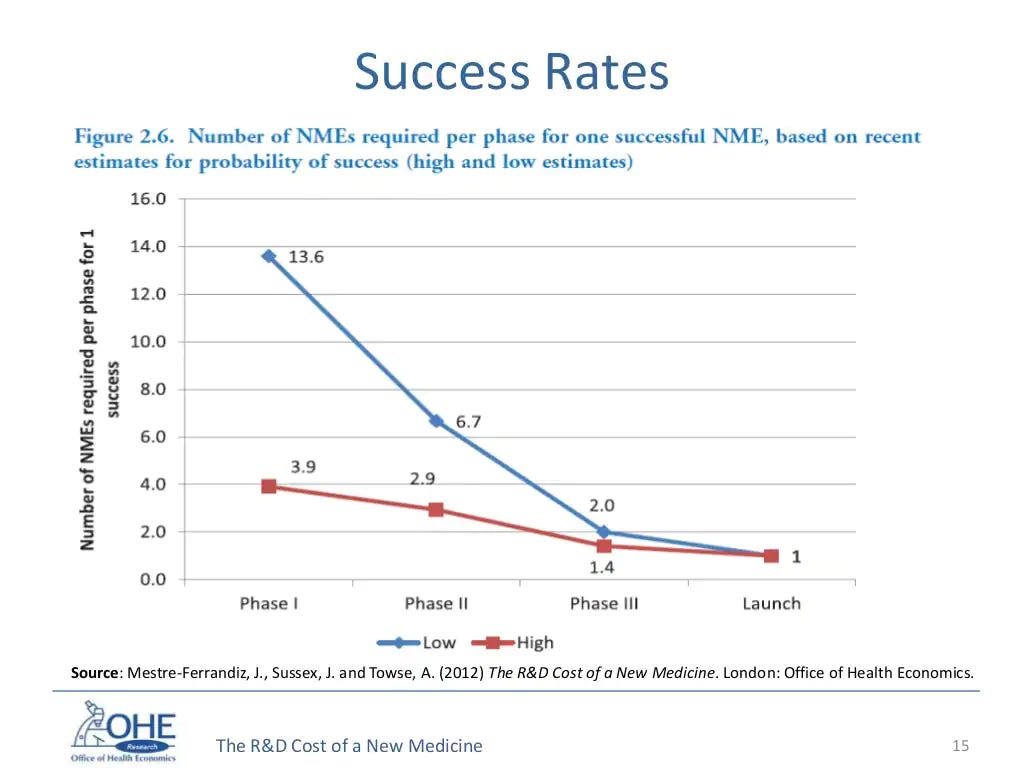

“Approximately seven out of eight compounds that enter the clinical testing pipeline will fail in development,” DiMasi said. “Put another way, you need to put an average of 8.5 compounds in clinical development to get one approval.”

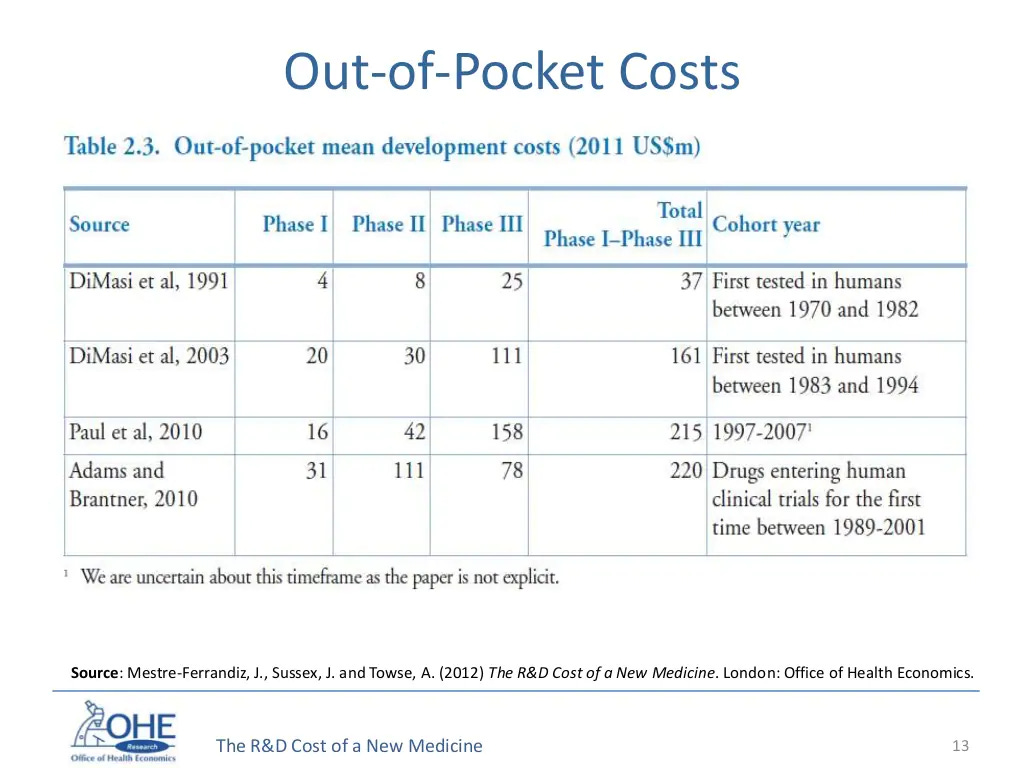

Now a look at the actual out-of-pocket-costs that a drug company would have to shell out to get approval. You're not really talking billions per drug, you're talking a couple hundred million. And in this era when a couple hundred million is a semi-good Series D, it's surely okay for it to cost that much for a potentially highly lucrative drug to be tested!

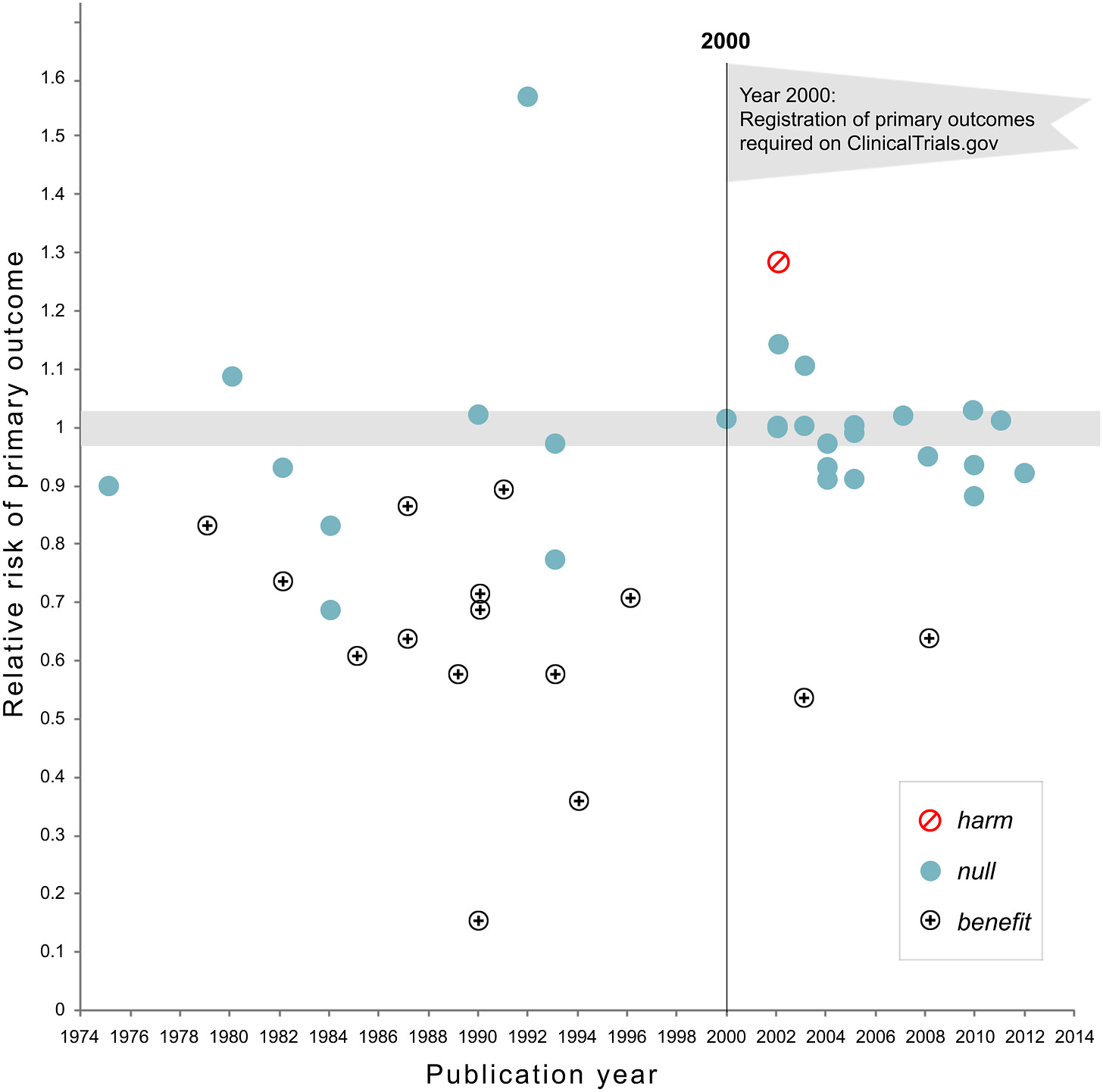

And if we look at the success rates per Phase, we see that it's also been declining over a period of time. Part of this is because companies have been intentionally focusing on areas which have the potential for high premium but are higher risk, like Alzheimers, or Diabetes, or rheumatoid arthritis and cancer.

The % chance of success is low (again, this is the equivalent of a large Series D for a technology startup) but I'm not sure we should be worrying all that much! I'd be far more worried about the fact that we're finding so fewer drugs these days that can pass muster, rather than that regulatory barriers are making drug development far more complicated.

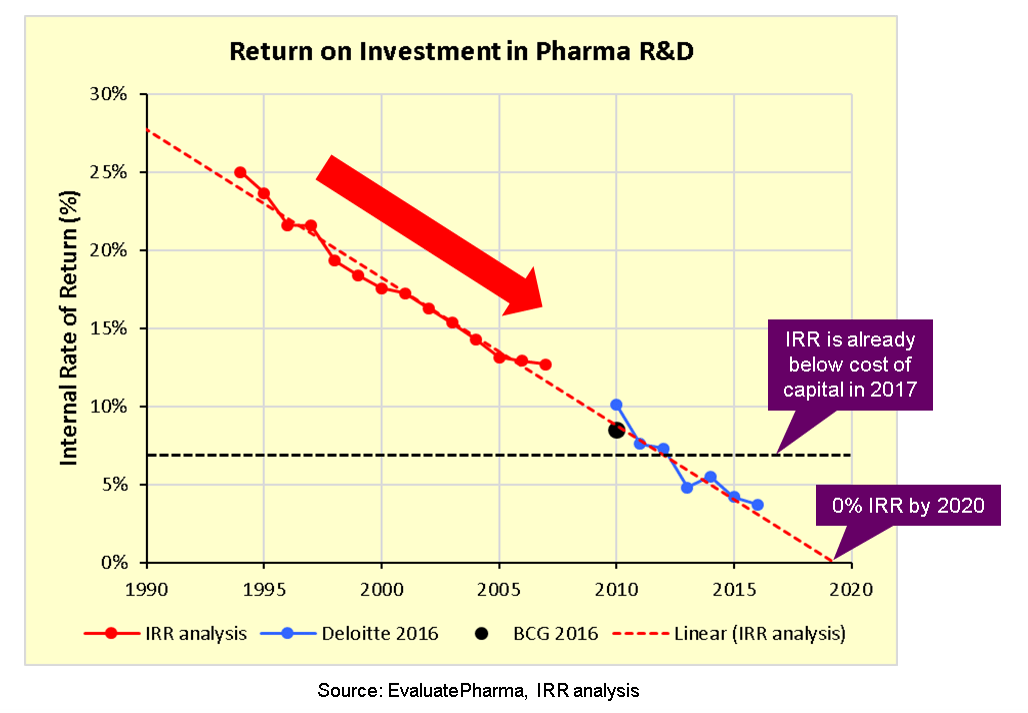

The return on investment in pharma is broken because the drug development pipeline is broken.

In fact, looking at this I think we have a pharma company concentration problem. We have a Venture Capital industry that routinely invests $100B a year nowadays, and still expects 2-3x cash on cash return, but we're worried about the pharma industry?

Surely the problem is that while there are 10,000 VC firms making bets, here there are much much fewer pharma companies who have to make all of the bets themselves.

The problem here is not that the pharma companies have to spend a billion dollars, the problem is that they have to spend a billion to get a successful drug. I mean, maybe the regulators are more risk averse. But so far it seems to be that the problem is slightly different, and altogether harder, in that we're just far worse at finding drugs that work!

And this isn't theoretical. If we look at the biggest success story recently, BioNTech, they arguably did exactly this. Developed a highly risky and unique technology over 10 years (2008 founded till 2018 when they signed a partnership with Pfizer), and reaped the benefits. And they did this with a c.$1Bn investment spread over half a decade.

What's more, the large pharma cos know this. They don't focus on developing drugs inhouse. They focus on buying:

A total of 62 products — 44 from Pfizer and 18 from J&J — were listed ... discovery and early development work were conducted in house for just 10 of Pfizer’s 44 products (23%), as listed in Table 1. Only two of J&J’s 18 leading products (11%) were discovered in house, as shown in Table 2. The 34 Pfizer products discovered by third parties accounted for 86% of the $37.6 billion in revenue that its 44 leading products generated. The 16 J&J products invented elsewhere accounted for 89% of the $31.4 billion that its 18 leading products generated.

So the idea that it is the FDA regulation that is increasing the expense per drug that's causing the pipeline to dry up doesn't hold up!

In fact let's look at the Silenor vs Sinequan story that Scott wrote about, the truly enraging one about how there's the same drug being sold at $10 Vs $250 because one passed FDA rules.

Scott suggests that the pharma co makes around $10-25m a year from this pill. Which seems ... ridiculously small? The economic case to do something that would result in getting that doesn't seem super worth it. And especially if you might just get undercut in price by 25x if there's even a half-sensible doctor (like Scott) who will prescribe it off-label.

But there's a few narrative violations:

Sinequan seems to have been discontinued in the US, mainly (it seems) because it was too cheap and generic

Silenor spent a total of $108m in R&D over 6 years to make this insomnia medication, but it's a crazy entrenched market which means they had to price high to make any money from this

Bear in mind, even if the total cost was $170m, and they make $10-25m a year, that means it will take them at least a decade to break even (assuming no discount rate). That's not a great return

In fact, I'd look at the current situation with Silenor and Sinequan as a positive situation, not a problem.

The insurance companies can tell their doctors "hey, here's a drug that's 25x cheaper, prescribe that and we'll cover you" - you know, the private incentive

The doctors, if they are educated and knowledgable, can do off-label prescriptions

The drug company which is willing to gamble on spending money both getting a known chemical through the FDA process for various indications, and take on the burden of advertising a seemingly generic drug can try to create and corner a market - which is fair enough

Attempts at solutions

The fact is that the problems articulated with FDA fall into three varieties of complaints:

They're not proactive enough: they don't cross-allow items like Silenor and Sinequan, different drugs with same compound but approved for different illnesses

They're not rational enough: even when cost-benefit analyses are overwhelmingly positive, they don't move, protecting their downside risk

They're not nimble enough: they don't move fast to approve things like vaccines

These are all valid criticisms. This isn't meant to be an FDA apologia, but is a look to show how bloody complicated the damn organisation is. Which means that if your idea of a fix is quick and easy, chances are that you're missing something. The solutions for the above problems would have to be:

Proactive: They need to have some kind of a function that does cross-validation and testing, and enables "off label" usage to be made "on label"

Rational: This is much harder. FDA does do cost-benefit analysis, but they will always be overwhelmingly risk-averse because that's what we ask of them. Unless the society stops blaming FDA if a bad drug or device gets through this can't easily get changed. The best they can do is to not restrict off-label usage too much, and have a presumption-of-effectiveness for a wider class of drugs (long as they're safe enough), which goes under a different threshold

Nimble: Again, it's a massive organisation so I don't see how this can happen short of an entire organisational overhaul. One way to get around it is simply to throw more organisations at the problem, and inf act this is actually what happens (Medicare doesn't just say yes to only drugs from FDA, they say yes to drugs rated safe by a bunch of private organisations like NCCN Drugs and Biologics Compendium)

At least that should be your strongly held prior. But there is a broader point here too, on how you should decide on the right strategy when optimising amongst:

Strict requirements on downside protection (FDA wants to make sure drugs are safe, effective, and marketed appropriately)

Flexibility to adapt to new circumstances (with a fast moving situation, like a pandemic, they need to move faster)

The problem is that these aren't mutually compatible all that easily. It's very hard to cover a mandate of covering a whole bunch of overlapping problems, to full satisfaction, and then to also ensure you're easily going to be able to move fast when faced with new circumstances.

FDA, sensibly, tried to solve this by creating, for instance, Emergency Use Authorisations, and IND to run in-hospital trials. Some of the EUAs even have hard deadlines from what I understand, so you can't dilly dally too long. Which, it has to be said, sound exactly like the sort of enhancement a really smart person would think up to solve complicated situations.

If any of you have tried designing questionnaires for surveys you'll see the problem here instantly. It's so easy to think of new things to add, it's very hard to remove anything.

The problem is that every new idea and mechanism, once thought up, becomes part of the superstructure of the system. It's another mechanism that needs to be analysed, and assessed, and monitored, and implemented. It requires data collection and data analysis, and data validation and meetings to go through the results of the collection and validation and analysis.

So the fixes we're talking about will naturally be a few "nuts and bolts" fixes, things that seem relatively straightforward to do (maybe), and a few radical approaches which need to be experimented with if we want to stave off the eventual ossification of the organisation.

Nuts and bolts

None of this is in any way supposed to be Leibniz-ian, or to somehow argue that the current state of affairs is in any sense optimal. Scott raises objections to the current functioning of the FDA that are entirely on point. And they absolutely need to be solved.

And so here's a bunch of things where we should probably just get the nuts and bolts right. With the FDA it might be, for instance:

If something is authorised in EU and Australia, for instance, default to an approval while doing whatever extra work needs to be done

Decouple safety and effectiveness considerations from the "what should be reimbursed" question, as that's an American healthcare tradition that's, frankly, kinda crazy

Create a publicly visible prioritisation system for drugs/ devices, and use that to revise meeting cadence

Create a specific part of the organisation to focus on making off-label prescriptions on-label

Figure out if we can let companies do Phase II/ III trials in an overlapping fashion more often, to speed up data collection

Allow human challenge trials, and then examine it for actual potential ethical violations, rather than saying no first!

These aren't particularly controversial in and of themselves (some of them anyway), and are the sort of common sense changes that can be pushed for by folks wanting change everywhere!

Cost benefit analysis - the Alex Tabarrok Rule

More broadly, the giant gaping hole from an efficient markets point of view is that we (me, you, Scott) shouldn't be able to so easily identify holes in existing, mature, sophisticated institutions to substantially improve them. However, I call this the Alex Tabarrok rule, people do seem to accomplish this task relatively easily and relatively quickly and relatively frequently.

Why do I think it's easy and quick? Because Alex did this in blog posts on a real-time basis during a crisis such as Covid. I don't think he was running RCTs on the side necessarily, yet he somehow managed to reach the right conclusions repeatedly.

The difference, far as I can make out, is that he did something I first asked my analyst to do close to a decade ago. To run a cost benefit analysis. If you don't have confidence in your costs or benefits, you estimate. If you don't have confidence in your estimates then sure, there's a reason to delay, but at least let's not pretend that this epistemological black hole is our default state of being!

What this means for an organisation as large as FDA is that across multiple layers there will be varying degrees of guesstimations that happen. The acceptance of that throughout the organisation is a remarkable challenge. And that's because while everyone there is very smart and very comfortable being the person making the guesstimations, nobody is happy to let someone who works for them make it.

Nobody wants to be the one to defend it, because by definition they are estimates. Being risk-friendly is the kind of thing that sounds good, but really hard to embed inside an organisation, especially one that's constantly under the public scrutiny and where the costs of failure are so public!

Adversarial Selection - Who regulates the regulators?

Now onto the slightly harder, more systemic, points of how to encourage the organisation to actually be more flexible and move faster.

One of the biggest issues we deal with is the fact that laws and regulations are passed whenever something acute happens. There's an epidemic of false advertising, FDA passes laws. There's a financial crisis, SEC passes more laws. There's thalidomide poisoning … you get the picture.

The problem is that the overlapping layers of rules and regulations imposed don't exactly create a smooth contour like we'd want. It creates jagged edges and frustratingly large gaps all over the place. Finding bugs shouldn't be a constant.

We need to make our rulemaking more responsive. We need to treat rules as experiments, try to analyse the results, and create mechanisms to both ease their passage and ease their repeal. We need to start treating existing rules as malleable, we need to treat our bias to solve problems by adding things, not removing them, as something that can be changed.

A study of 1,585 people across 8 different experiments showed that our brains tend to default to addition rather than subtraction when it comes to finding solutions – in many cases, it seems we just don't consider the strategy of taking something away at all.

Like most rule systems defined, this too might be a bad idea, but at least its an idea worth testing. Not having negative control on existing rulesets seems like an important problem! And if the sheer complexity of removing rules regularly seems overwhelming, we could even just make the threshold to make a rule disproportionately higher than to remove a rule.

Turns out it has a long history, right back from the Roman times.

The precise origins of sunset clauses are contested. Some locate their roots in Roman law but the first philosophical reference is in the laws of Plato. At the time of the Roman Republic, the empowerment of the Roman Senate to collect special taxes and to activate troops was limited in time and extent.

In the UK, sunset clauses were employed by parliaments by at least the time of the reign of Henry VII and appeared in statutes by 1500. The series of Habeas Corpus Suspension Acts enacted from 1689 all had specified expiry dates; up until 1777, these acts lasted on average for five months. In the US, Chris Mooney traces the history of sunsetting back to the writings of Thomas Jefferson. Jefferson believed that a version of sunsetting sprang directly from natural law: “Every constitution… and every law,” he wrote, “naturally expires at the end of 19 years,” which was considered the length of a generation in his era.

Right now, it seems more related to emergency legislation which is meant to be temporary. This applied to the aftermath of 9/11, the war(s) on terror and the coronavirus acts.

There are occasional spots where this has been tried, though arbitrarily, like in Texas.

Under Texas law, all agencies – except universities, courts, and agencies established by the Texas Constitution – will be abolished on a specific date, generally 12 years after creation or renewal, unless the Texas Legislature passes specific legislation to continue its functions. A 12-member Sunset Advisory Commission oversees the provisions of the Texas Sunset Act.

And does it work? Yes!

Is Sunset effective at passing good government reforms? Yes — a strength of the Texas Sunset process is the high success rate of the Sunset Commission's thoroughly vetted recommendations becoming law. Since 2001, 80 percent of the Sunset Commission's statutory recommendations to the Legislature have become state law.

We need to bring this idea back, and enhance it substantially! It’s not a panacea, but it can help.

And what happens when we remove more than needed, or when we add more that's unnecessary?

Luckily we currently have a system that (highly imperfectly) does the job of trying to speed up getting to the right resolutions from imperfect data in a messy world. It's the adversarial method. We employ it in our entire judicial apparatus, in our decision making apparatus from corporate boardrooms to political debates, in academia amongst varied explanations.

If I had to make another case for billionaire philanthropy, creating a public institution who is supposed to argue against public institutions would be amongst the top suggestions. Not a thinktank that criticises from afar, rife with myriad conflicts of interest, but a public institution who tries to make the case that FDA, or FAA, or CDC, or any other acronym-ed agency, does their job better.

My most out-there take is that we should have an anti-regulator, who is entitled to consistently surface laws that have low thresholds of cost-benefit, and who can push the various arms of the government to edit or repeal them.

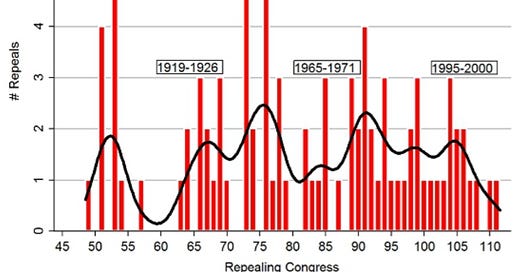

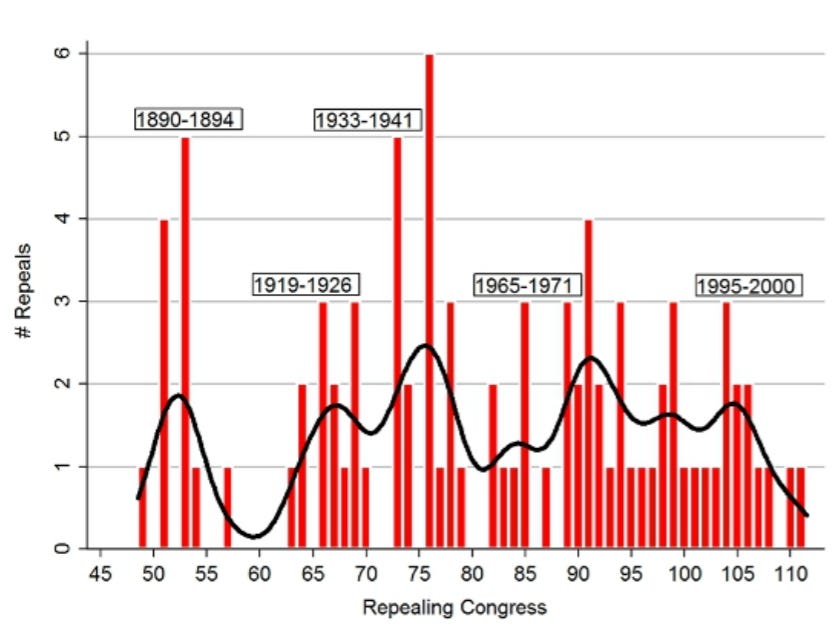

Congressional repeals, 1877-2012

Yes, the creation of such an entity would create new avenues of lobbying and new avenues of possible coercion, but surely it can be a bipartisan, generally respected, organisation like the CBO, who can put forth the arguments on which laws have jumped the shark.

Right now we expect the general animosity amongst the parties and the goodwill of the senators to be sufficient to both pass laws and repeal laws, and that doesn't seem to be working!

So whether it's for laws passed or regulations imposed, it makes sense for us to have an anti-FDA, an anti-FAA or an anti-SEC to push against the proposals and ensure the regulations that have been passed in the past, which have come up for sunset, are no longer needed.

The anti-regulator can even be pretty small by design, so they can be nimble and they can be focused - I mean, the CBO is 250 employees, which is not particularly large.

The constant scope creep of added regulations is difficult to see when it comes through. We'd probably end up with regulations that are added back in because removing them is more costly, but that's perhaps a better equilibrium to aspire to.

Excellent piece. We need to not only exit the FDA but also exit any system that supports it. Systemically that would mean making decentralized and transparent systems. We could build parallel ones like what Balaji describes in his book The Network State. Or we could build ones that plug into the existing systems and gives the control back to us. Like this:

https://open.substack.com/pub/joshketry/p/worried-about-voter-fraud-lets-build?r=7oa9d&utm_medium=ios&utm_campaign=post

This piece is gold. I’d argue that regulations (which are laws passed by regulatory agencies like FDA or SEC) should include a section about implicit assumptions. In other words, the regulation should specify which problem this regulation will solve or help. And then automatically sunset if the regulation doesn’t reach its own goals within a set period, say 10 years.