I

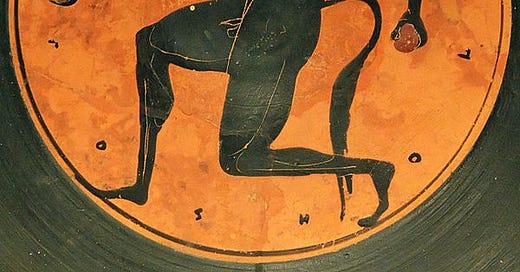

In mythology, the Minotaur was the offspring of a human, Pasiphae, and a white bull. Not a natural occurrence one thinks, since this had Poseidon’s hand behind it. Pasiphae created a hollow wooden cow to complete the act, presumably because the bull wasn’t easily persuadable otherwise. He not only had the predilection for living in a maze (weird) but also the unfortunate problem that being a hybrid he didn’t have natural food sources, forced to rely on eating humans (weirder).

This isn’t unusual. We have a whole lot of gods (Anubis, Horus, Sekhmet, Ganesh), ancestors (nephilim) and creatures (chimera, harpies, sphinx, centaurs) who have similar characteristics.

All of which brings up a question. Well several actually, but one in particular for this essay. This doesn’t seem all that common in the world at large. Not just the macro head-of-creature-X on body-of-creature-Y constructions either.

When animals split into multiple species, occasionally they cross-breed. At the boundaries. Most of the time when this happens, the offspring isn’t particularly successful playing the evolutionary lottery. For example, when a lion and a tigress love each other very much, you might get to see a liger. Its much larger than its parents, but sadly are azoospermic. They’re evolutionary cul-de-sacs at this point.

Plants however seem much more relaxed about this sort of thing and hybridise rather easily, though mostly under our supervision. Corn, for instance, outcompetes pretty much everything else in terms of yields and responds to fertilizers, and in general makes the nature version look kinda sheepish. Rice too, in China, shows the same tendency, with the hybrid super-rice (not a real superhero) producing up to 15 tons a hectare.

So I started to wonder, is it a plants thing? Are plants better than us? Did Alan Moore have a point when he wrote swamp thing?

Mostly though, can this help explain what’s going on with the new types of organisations we’re having to deal with? Are we dealing with minotaurs or just evolved mammals?

II

I started thinking about this as we see the types of organisations go through a period of rapid change around us. We used to have a couple of reasonably distinct nodes. On the one pole was academia, where there existed a complex and byzantine system of rules, norms and increasingly vaguer illusions of grandeur.

On the other end are the highly fertile and ever changing world of startups. Which is very much the gamete stage of commercial ambition, where initial wedges get defined, business models get created and innovation is made real in the world.

Both these poles have had many interactions, successful and unsuccessful, over the decades. Sometimes they work remarkably well, where the innovations that happen in one part of the system gets caught by other parts of the system and it all works reasonably well.

Semiconductor industry is arguably a case in point. As is quantum computing (such as it is). Or most aspects of telco information processing. Some aspects of biotech are very much in this vein.

But the core hypothesis on both poles is the same - the existing institutional setup is broken, so we need to do better.

On the one end you say, academic institutions are broken, so we’ll build our own. Thinktanks are corrupt, so let’s build our own. This creates the need for new types of institutions to come up - whether that’s Altos Labs or New Science or the myriad others.

On the other end you say, existing companies are ossified, they don’t innovate, so we need to have disruptive innovation. Y Combinator is formed, startups are funded, and they (some) go on to do amazing thigns.

However, by its very nature, building something new allows you to create white-sheet versions of the organisations, which helps you be more efficient at least with regards to specific problems or specific problem-areas.

So a lab dedicated to studying longevity will be able to do better than an all-purpose university research center, even given similar amounts of funding. The self-selection of talent who want to work on that particular topic, and the focus that comes from working on that one thing you care most about come together to create some form of magic. Like iron filings pointing together at a magnet, motivation is a powerful force.

But while startups have gone through its chasm of fire in its very conception and conceptualisation, funding availability, talent pool recognising it as a viable source of work, and general societal admiration.

The non-profit equivalent, those that are trying to supplant part of the work that academia ought to do, and those that are creating hybrids that comprise some combination of research + commercialisation, haven’t gone through this yet. Which means we’re likely to see a Cambrian explosion in this sector, and as these things are wont to do we might also see a Cambrian-Ordovician extinction event too.

Part of this is because the fledgling institutes have to go through the baptism of fire to become strong enough to challenge the megalosaurs of the academic world. But part of it is also because hybrids have a hell of a time adapting to an environment that fits the existing fauna just so well.

So we find, for instance, FROs emerging because we found that the link between academia and full-fledged commercialisation isn’t very strong. Or XARPA because we find that particular types of projects that lead to innovation are missing from the existing ecosystem.

Are these equivalent to finding previously occupied but now abandoned niches? Or are they the equivalent of creating a new hybrid organism that will be outcompeted by its parents? Or indeed is this a time of ever increasing changes in the landscape overall, times when hybrids come out and become the dominant species, finding and exploiting previously nonexistent but recently created niches.

III

All of which brings to mind the question of how we should look at these new institutions. A way to look at the Cambrian explosion of science labs is that its trying to do for academia what startups have done for commercial companies. This is a necessary part of having a complex and sufficiently energetic substrata that allows us to minimise the cost of experimentation and let new flowers bloom.

One option is that this is about defining your goals. If the existing organisations are unable to meet your goals, either because of the way they evolved or because of the way they are structured, then we will have to create new options.

For instance, that time when we tried to force wolves into fitting in our handbags since before we knew how to make handbags. And in the process we’ve made chihuahuas and bulldogs, as evolutionarily backward as they are in terms of being able to survive in the wild. But they do exist, and survive, if not exactly thrive, at least until nature comes up with tiny handbags as chihuahua carriers in the wild!

Another option is that this is a fact that tells us more about the landscape. What this means is that evolved things seem to be better suited to their niches than designed things. Which seems like a truism, but it speaks more to organism-niche-fit rather than evolved vs designed.

What this means is that if we’re genuinely seeing a landslide shift in the ecosystem of sciences where either theory gets freely redefined (think citizen scientists in companies eg AI), ability to experiment gets easier (think biohackers) or boundaries of scientific fields itself becomes transparent (think emerging segments like longevity perhaps).

A third option is that this is the usual generational hubris that attempts to rederive those evolutionarily fit organisations from scratch, only to bump up against them like mammals against the dinosaurs before a big rock helped us along. This one’s a bit too get off my lawn so I discount it accordingly.

A last option, which gives me the biggest pause and is my most likely candidate, is that the reason startups work is because they have one clear commercial output to optimise for. It’s money. If they earn more they win. If they earn less they lose. At the very least we can see how this functions over a period of time.

With organisations that lay on the other side of the spectrum, the academic side, the original impetus lay in the seemingly intangible benefit of prestige. But can this survive the lack of gilded halls? It’s possible, but unclear. It used to be possible in the good old days when patent clerks could write groundbreaking papers, but less so these days.

Can this work? Yes. See Deepmind for just one example. But its also hard. Precisely because success isn’t easy to see, tangible to measure, or legible to the rest of the world.

As new vistas are found and explored, this might probably become easier to visualise, but right now we’re all peeking over hills. I don’t know what this will look like, but this is something I’d like to understand better. In the next essay I’m going to try learn a bit more about what the map of these science labs looks like outside in, see where the negative spaces lie, and whether it feels like something that’s equivalent to a new species that can win.

I'm kind of suspicious of placing "academia" and "startup" as the main players where new ideas evolve. They are certainly both the main drivers of funding. But consider:

- Linux Kernel

- Bitcoin

- GCC

These are all projects that define the modern world in ways that are impossible to grasp, like, cut out one of them and you might notice 5-10% ripples in global GDP kinda thing.

<there's an argument to be made that they would have arisen anyway. But Riemann had all observations and mathematical tools and framing to propose general relativity, yet it took another century>

There's also a huge amount of projects that "feed off" academia or corporations, as the side projects of employees, or as a tool for something else.

CUDA was envisioned primarily as a tool making animated tits and bullets bounce more realistically and it's a matter of chance that it ended up being the fundamental technology for solving half-century long problems in particles physics, macro-molecular biology and arguably psychology (if you view advertising models as modeling human behavior).

I think there's a non-zero chance of there being a process that's something like: Many worthwhile inventions are created by half-insane people working on what they are interested in. Then whatever institution happens to be close to the inventor[s] gets the credit as its meta-generator, because by definition such investors are driven by neither status nor money they don't care to protest. The three examples above are exceptions where this didn't happen.

Read Fortune's Formula recently, and marvelled again at Bell Labs. I have always wondered what made Bell Labs successful. So many geniuses and important inventions came out of that place that it doesn't seem like mere coincidence. I don't know which category you would place it in, but do you think a digital version of that is possible/already exists?

Another thought I had was about how the nature of work has changed quite a bit. Do you think it's more difficult to do focused work in this hyper-distracting era? Because I see the means for collaboration and the ability to find information has grown, but can't say the same about that obsessive hobbyist kind of involvement in work that seems to be missing now. Could just be me being nostalgic for a time I never knew :p.