On Smilodons And Designing Success

The Three Immortal Cs, and the success of bottom-up movements; Part II of trying to understand New Research Organisations

The question we looked at in the first essay was whether we could place the new groups of research organisations into a familiar taxonomy. To answer the question whether these organisations are most similar to:

A new genus to supplant part of the work of academia and/or startups? Which would require it to be an evolutionary outcrop fighting to grab its niche from pre-existing large players. i.e., a Smilodon surviving in ancient Americas, evolved to hunt bison, vs the Liger, the azoospermic large cat that’s a vestigial remnant at the end of an evolutionary tree.

A better version of think-tanks, evolving into providing funding alongside insights and papers? Which would require it to outcompete the thinktanks themselves, which is feasible, akin to an ape outcompeting its predecessor.

Something akin to Open source, i.e. a new type of org created through bottom up pressure? Which would be the equivalent of the aforementioned Smilodon carving out a niche for itself in an uncaring forest.

The next question is essentially, will they last a long enough time? Are these fleeting glimpses of an evolutionary form in flight or are these likely to be longlasting!

So let’s have a look. First, at what constitutes immortality for an organisation, and later what it means to be similar to an evolved organisation instead of a designed one.

I - The Three Immortal Cs

I've been watching Foundation, one of my favourite works of fiction, and it struck me how unlikely it is that an Empire could stand for so long. 12 millennia of a government, even with upheavals in the middle, is remarkable.

It mainly got me wondering, what would it have been about it that made it so long lived. They are sharks, in the evolutionary sense. Or jellyfish. And so I decided to look at a few such Methuselahic organisations from our earth.

Churches and religions have survived for millennia. The Catholic church saw schisms and wars and crusades aplenty hut held together.

Colleges have a long life. Cambridge and Oxford have several centuries of history behind, and looks set to continue for several more.

Cities, which survive forever! Jericho still exists ...

There is a fourth C, which is corporations, which are made to be immortal though in practice survive a mere century if they’re lucky. They are subject, intentionally, to the vagaries of demand and subject to the vicissitudes of execution

The shinise businesses as in Japan go generation to generation, and the oldest has been around since the 700s. But they pale in comparison to the exceptional longevity and strength that the three Cs exhibit. Despite China’s urgent attempt to build multiple brand new cities, its not been particularly successful.

The key to all of them is that the leadership knows what it's obligations to the group are, and they don't change. The organisation doesn't try to grow or expand.

The church does proselytise, and that acts mainly as faith adherence for its adepts and brings new blood in. But proselytisation is not its primary function. Growth isn’t its implicit motivator.

The only way for a longer life is to have an unchanging motivation in your constituents. When those who weaken their motivation, they usually leave. In fact, with the church we've seen that as motivation has (very recently) declined, the Nexus of belief has indeed shifted.

Maintaining internal coherence and motivation is the main job of the leadership. Even growth itself acts as a means for achieving that.

What's the relevance to the new science organisations in the subtitle? It's that the three C's show us a way to find longevity in their chosen forms, and the wonder is whether the new type of institutions can come anywhere close.

Perhaps this is an unfair comparison. After all, most companies don't survive centuries either. Maybe a better question is whether we even find a need that these new organisations are scratching.

II - An Evolved Organisation

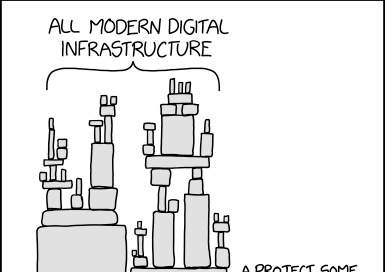

The canonical example of a “third rail” that stands apart from the giant poles of corporations and academia is open-source. It’s a fact that whether its linux or gcc, these are foundational efforts, done cooperatively by masses of volunteers, to hold up most of what we consider our collective technological infrastructure.

Open Source as a concept isn’t new. People have worked together to build stuff for the fun of it forever, for instance by Stallman for GNU. Open source as a new species in our organisational menagerie however is new. having been kickstarted by Netscape Communicator having been set free for anyone to edit and use.

This “free software” ended up seducing a fair number of people to come over to the free side, to create a movement that would later be called “open source”. Tim O’Reilly, Linus Torvalds and others joined force. Linux was born not long after, and became a Schelling point for geeks the world over.

open source is an intellectual property destroyer. I can't imagine something that could be worse than this for the software business and the intellectual-property business.

Now, its clear that the movement struck a chord. That chord being comprised of three strands - 1) developers want to work with other cool developers on whatever they’re working on. 2) developers want to work on cool stuff. and 3) working on cool stuff with credible output is a hell of a CV.

All three were existing internal impetuses not particularly satisfied by existing structures. Once it became possible to be an individual renegade and gather a group of people to do this, it started happening. Its similar to the gentlemen scientists that used to litter the landscape in the 19th century or self-taught machinists. The urge to build cool things is innate, and people do whatever they can to satisfy it, like when the Wright brothers used their bicycle repair company to pay for pursuing human flight!

But is this a clear genus of software that is now here to stay? It feels like it, we shall see!

This could be an argument in favour of just attempting to find and encourage the next Linus. If we’re successful in encouraging a fraction of this talent to develop, or at least not stamp it out, that would indeed be an achievement. Even better, a counterfactual achievement.

The value something provides is a function of its counterfactual importance.

But it is also an argument in favour of letting things be. Clearly despite the draw of massive corporations, academic institutions that at best were even more attractive than they are today, and government institutes galore, the geniuses who engaged in OSS movement did so of their own volition.

It was a bottom up movement of people wanting to do something. It was not a movement of people wanting to encourage other people to do something.

So when I look at open source as a third pole amidst academia and commercial world, I see it surviving precisely because it's not a hybrid created and maintained by our efforts, feeble and short-lived as they usually are. I see a bottom up evolution that pushed a movement into being.

Which segment will the New Research Organisations lay in? I don't know. While there's discontent amongst the scientists all over the place, there's also not enough bottom up movement to craft something akin to OSS.

When I look at the overwhelming interest in DAOs, its this that makes me hopeful. The bottom up adoption of a new style of self organisation that could succeed. Will it? No idea. But the fact that its scratching an itch that seems to exist inherently in people is a good sign. There are no guarantees of success, but there are better or worse pot odds.

If we push back in history, a corporation itself was a new type of organisation that set boundaries for a particular form of commercial activity. That succeeded beyond what we would’ve imagined.

Are DAOs a new species? Yes. Will they gain market share amongst the existing org jungle? Maybe, we’ll see.

I don’t know whether it is indeed a Liger, or just the magic of Carcinisation at work turning them into regular old orgs, but it’s something I’ll watch with bated breath.

III - Now What

So far the new institutions that have emerged seem to stem from three main impetuses:

The urge to develop talent that previously lay untapped in many domains

The feeling of dissatisfaction for some within traditional strictures - eg academia

The former provides funding, and the latter provides those who get the funding.

Is this akin to a self-directed process the same way as OSS developed? Not quite. It feels more like the creation of a new ecosystem by fiat, where there is simultaneous agreement amongst various parties that problems 1 and 2 have to be solved. As long as those who are agreeing are able to provide some amount of funding, we can probably kickstart a market.

Will it succeed in creating the niche and having a positive feedback loop emerge from the work that’s ongoing? It feels like it might! But it’s worth noting that the impetus here is a negative one, i.e., it’s one that tells us what existing poles are bad at (academia is too bureaucratic, companies are too shortsighted) rather than a positive one (we can work on this together).

In many ways web3, whatever that moniker ultimately comes to refer, is probably a stronger representation of an ecosystem that’s developed bottom up than the new research organisations.

But sometimes you do need to jumpstart ecosystems. Maybe we only needed a few people to kick-start OSS at first, with Stallman and O’Reilly and Linus. But if we want to jumpstart the ecosystem to make it closer to what it is today, you need to inject far more dollars and structure to the problem. It's not about just the very top of the curve, but the cast majority who lay at the high quartile but perhaps not the very top decile.

I also don’t think the combination of a few research organisations dotted around, working on pet problems, and a few funding organisations acting as supportive Medicis are enough here. We need them to be knit together to learn from each other to truly be able to create the decentralised equivalent of what exists today. That requires a decent data collection and analysis infrastructure, a far better set of APIs to connect amongst the organisations, and a more comprehensive coverage of the organisations themselves.

One of my ongoing attempts is to try and create a taxonomy, or a periodic table, of what this brave new world will look like. But that’s for Part III.

Which means the new orgs are in its fragile chrysalis and we don’t yet know how it’ll develop coming out. Will it be a mainstay of our economy in three decades, at par of a force comparable to the worlds of prestigious academia or vibrant entrepreneurship? I’m relatively confident it can carve a niche, but what shape it’ll be in once that happens is up in the air!

I did my thesis comparing how big a change was made in social terms during two periods of time in the Quaker religious community. During one period, the change was driven by a bottom up model, in the second, one group called for change and everyone else, said "ok, we will try." The second attempt didn't work. One of the reasons for that is that the people who needed to make the most change weren't involved in the process, another was that the first attempt took decades, while they gave up after less than two decades for the second. Lesson: Change takes time - lots of time - and bottom up while involving those who need to make the most changes are crucial.

> you need to inject far more dollars and structure to the problem

Interestingly enough, one thing that always bothers me is that money comes at the "expense" of injecting some structure into an org/project. And that's one niche thing that might not happen with e.g. a DAO kickstarted by token sales.

Similarly, people often try to incentivize the injection of a structure with money or the promise of money (join this college system and in 6 years from now Google will hire you for so-and-so amount).

Maybe there's cases where the two are damaging to each other if shoved together in the same system.