I

This is a story of two types of wars. This is also a story of two cultures.

Genghis Khan went and built an empire, like nothing the world had seen before. And once built, in the middle of blood and horses, he had to deal with the small problem of paying for everyone. So he introduced paper money, as early as 1227, and about a decade after that also had currency reforms and demonetisation.

Initially, the coins of the period were not labeled with specific numeric values. However, later, in 1241 coins entitled "The Currency of the Great Mongol Empire" were issued with "1" engraved on them.

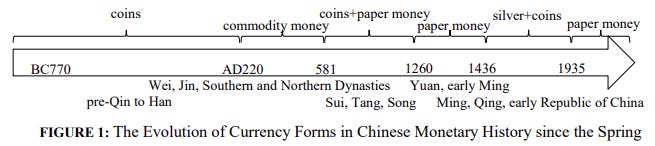

Song Dynasty, one of his conquests, had started using paper money at large by government fiat, solving a similar problem. It was first created as a sort of promissory note during the Tang Dynasty few centuries earlier, but Song took direct control over the process of depositing coins and issued jiaozi.

In fact this paper money is what most earlier visitors to China saw as the usage for paper. With complex woodblocks and coloured dyes to make it difficult to counterfeit, and a lifetime of a few years to recirculate, this quickly became a national currency. But along came Genghis Khan.

The Mongol paper currency, chao, we now know about because Marco Polo saw it during his stay with Kublai Khan, grandson of Genghis. And unlike jiaozi, this wasn’t backed by gold or silver.

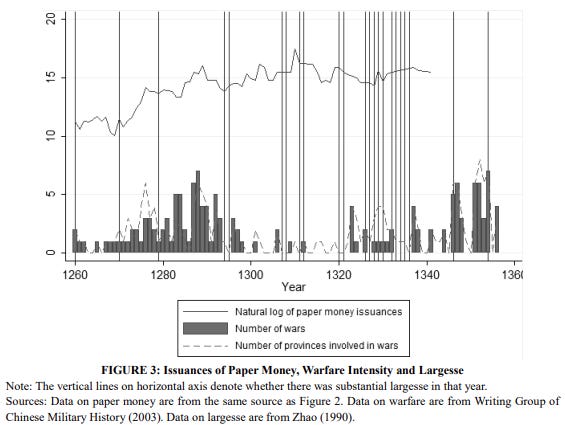

And the Yuan dynasty, successor state to the Mongol Empire, established by Kublai Khan printed ever increasing amounts of money which led to the dynasty collapsing. This is the first story.

In Europe, in the meanwhile, the Crusades also needed financing. Another set of wars, and another set of similar needs. How do you pay soldiers when you don’t have money. When Venice needed to defend itself against the Byzantine emperor, she decided to levy a forced loan on its wealthy citizens, not having paper money or easy inflation.

This started an entire process of creating more and more sophisticated debt. This increasingly structured government debt started becoming investment vehicles, and kickstarted the bond issuing revolution.

China invented paper money to deal with the fact that they didn't have enough precious metals to pay the troops. In India too, Muhammed bin Tughluq, the Sultan of Delhi and an incredible ruler (known for wildly different policy swings) did this albeit with brass instead of paper.

Asia here is essentially inventing inflation in a way to pay the soldiers, because they didn’t have enough coins on hand. Whereas in Europe, they came up with CDs and loan instruments first, as the Crusaders needed financing and Venetians took a loan to fight the Byzantines.

And this shift rippled through the centuries until fairly recently the latter part of the millennium they linked back together!

This isn’t a question of which one is better, since for the purposes of warfare and expansion they both saw plenty of victories and drawbacks! This is a question of which one of those brought about the longer term innovation for a country or a continent.

Ideas, once they get started in one place, come about as a result of its own internal cultural structure. Choosing the right way though unlocks your future, and choosing the wrong method can stop you in your tracks. It took a good four centuries for banknotes to be issued again in China, and only in response to the Taiping Rebellion.

If you don’t have money to pay your soldiers, usually considered a sensible thing to do, all you can do is to either print more money (inflation) or get money and repay it later (debt). But the consequences are quite different. The decisions made several centuries ago still ripple through today’s society.

II

The first is a question of why this historical accident happened the way it did. One option is that things happen because they happen, a Douglas Adams style tautology. It doesn’t require an explanation as much as an acknowledgement. But in that world there is little we can learn from the incident itself, and it doesn’t explain any of the latter differences amongst the regions either.

Kuang (1980) thought that although paper money in the Yuan dynasty had apparently stimulated domestic trade and economic development and that the government had taken systematic measures to make paper money circulate stably, it also must be noted that inappropriate policies in the late period induced chaos with the money in circulation and led to the collapse of the dynasty.

A second option is that it could only be thus. The problems they faced macroeconomically were the same, but the solutions were different. Why were the solutions different? Because the solutions required the existence of features that didn’t exist in both places. For instance:

Venice required the existence of large private wealthy institutions that were willing to lend to the government

For such lending to take place there needed to be systems and norms in place to facilitate such lending

For such facilitation there needed to be a reasonably clear system of laws that were well understood by the counterparties and also, crucially, that they were actually enforceable as if amongst equivalent parties

The existence of stronger private interests helped government debt to be usable in Europe, whereas lacking this option to get capital from others, the Khans had no choice but to try their inflationary method. So while the banking system in ancient China seems eerily familiar to us today, and back in the last few years of the first millennium, accepted deposits, made loans, issued notes, exchanged money and even did remittances, they weren’t exactly fit for purpose.

But with the idea that issuing paper money led them to the grim clutches of inflation returned the immediate disbelief in the idea of money-as-trust-signifier. And this meant that commodity money, in the form of bulk silver often, was pretty much the status quo.

Which also meant that the legal systems didn’t really catch up to the complexities required to make trust workable amongst counterparties in the financial system. After all, laws act as the scaffolding on which trust is built, and if the scaffolding itself isn’t all that strong then it all comes tumbling down.

The lack of this trust is what meant that, for instance, fractional reserve banking or long-term money deposits just weren’t developed in China. It meant that they had to draw upon reservoirs of trust that existed elsewhere, such as personal relationships and families.

Whereas in Europe we find something slightly different.

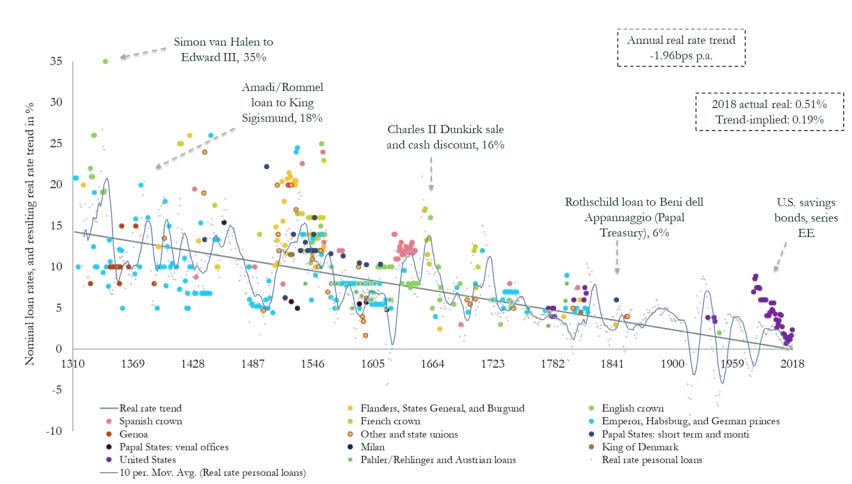

Outside of the urban financial centers of Northern and Central Europe in late medieval and early modern times, prior to the consolidation of debt on the national level, we frequently encounter sovereigns resorting to personal loans from “court bankers” (figures like William de la Pole in England, Konrad von Weinsberg in the Holy Roman Empire, or Jacques Coeur in France), or from wealthy merchants. Especially in war episodes and in the context of weak central bureaucracies, such practices supplanted more institutionalized methods of public finance until well into the 17th century (Fryde and Fryde 1963).

Even when taken under duress, it's still a much larger component of trust based loan-making to help sovereigns manage their finances. They, in the case of pledge loans in the 14th and 15th centuries, include the fact that repayment comes from income streams from taxation or tolls. These are long duration loans (over a decade) or even perpetual loans, which could not have happened without multiple parties of comparable power to debate the terms with each other, and trust each others’ actions to be both selfish and rational.

Are we extrapolating a tad too much from an interesting historical coincidence? Perhaps. After all there aren’t any counterfactual worlds to test this theory against. But it does feel like these were the only options if you wanted to pay folks and you didn’t have enough money - you have to either issue debt or you have to print money. Exactly what happened in our economy as well, during the crisis.

In Venice, the setting for our second story, the trend is remarkably similar in terms of professionalisation of the obligations-markets.

We have to wait until 1262 for secondary markets in Venetian long-term debt to be established, by a decree of the Venetian Grand Council, the ligatio pecuniae, which also fixed annual coupons at 5%(Tracy 2003, 21). This date marked the start of “continual speculation on the open market in government obligations” (Mueller 1997, 516), and almost uninterrupted market prices are recorded from then onwards in Luzzatto (1929). Following Venice, Genoa consolidated its various long-term loans into a single fund, the Compere, in 1340. Florence equally consolidated its debts in 1343-1345. Henceforth, it was known as the Monte Comune. The instruments of these city-republics could be pledged as collateral for bank loans, lent to third parties, used in lieu of money to pay private obligations and taxes, and the “vivacious” turnover gave rise to the establishment of both private broker houses and public debt agencies in charge of issuance and liquidity management (Mueller 1997, 453ff.; Pezzolo 2003).

While the immediate problems of remittances or lending were performed by specific institutional setups in China as well (piaohao and qianzhuang in this case), their ability to expand beyond their immediate businesses were limited by the liabilities and existence of sufficient legal protection.

But the fact of the matter is that in the absence of institutional trust there isn’t much of a choice. Your space of potential actions are limited. If the sovereigns themselves sit under the superstructure of codified legal relationships, de facto if not de jure, then that helps the rest of the society overcome their trust deficit and enter into longer term relationships.

III

Coming back to the two stories, what’s most interesting here is that the existence of multiple nexuses of power and an existing structure of speculation in sovereign assets can enable the creation of a different strand of financial speculation and freedom, addressing the envelope of what’s considered possible.

When the maker of monetary policy is also the maker of fiscal policy, as was the case in Asia, the possible deterioration of a carefully held balance to fund their wars is as inevitable as the slide down any prisoner’s dilemma. When the world is a tad more, for lack of a better word, decentralised, then you can get multiple nodes who can communicate and deal with each other.

There is no pat conclusion here, no suggestion of the superiority or inferiority per se. They’re just different tools in a toolkit. But they weren’t equally available to all parties. What there is is the understanding that in order to successfully navigate a complex economy, oftentimes the tools at hand seem like the inevitable choices because of historical circumstances. At the best of times we are blindly groping ahead to find a solution to an immediate problem, grabbing whatever comes closest to hand.

Finance has always been a superstructure we use to guide how we deploy our resources. I’ve always admired its existence as an egregore, combining our collective strands of trust and enabling us to build a future that a sufficient number of us believe in.

Just like playing a game, it's a way to help guide how we respond to needs and events. Like “how do we pay for this thing we want to do” or “how can we afford to invest in that thing”. These decisions that we make daily as a decentralised collective are ultimately dependent on the economic belief structures we choose to let govern us. It is the envelope of possibilities of those very fictions that results in the actions we end up taking.

Sometimes the stories we tell ourselves tells us about what we allow ourselves to think about in the first place, and those boundaries tell us more about where we’re going, than anything else.