People always put their money in futures they predict

A whistlestop history of investing theses

The life of money-making is one undertaken under compulsion, and wealth is evidently not the good we are seeking; for it is merely useful and for the sake of something else. And so one might rather take the aforenamed objects to be ends; for they are loved for themselves. But it is evident that not even these are ends;

Aristotle

I. The hard thing about this thing

I started with a pressing problem, which is how should I invest my money. It led me down a rabbithole, on the link between wealth and how people imagined the future, between beliefs and bets, and this is likely the first part of this exploration.

Sometimes I think about the world of investing as play-acting our beliefs in a particularly wonky universe. In the investing foxhole, there are no atheists. We create our own theories, act on our beliefs, cut the world into understandable slices, and then try and put our money to work.

Why do we do this? Because if we’re right, we make more money tomorrow than we have today. We win when the world moves in a way that we predicted or when we get lucky.

But it’s hard. Today, if you were to open up your favourite trading app, you’ll see some 5000 stocks and 8000 ETFs, not to mention options and FX and all other assorted ways to test your hunches. How do you even choose amongst these?

Well, you could listen to someone else. 60% stocks and 40% bonds used to be conventional wisdom, and it isn’t bad. Or you could add an equal measure of Gold and Cash, and get a Cockroach portfolio. Or you could use 90% stocks and 10% government bonds, for the Buffett portfolio. Are any of these “right”? Well, not in any objective sense, because the future’s unknown. But if you have any beliefs at all about the future, sure some of them are better!

If you think the future of corporate American looks a lot like the past of corporate America, the Buffett portfolio is great. If you think the future’s pretty unknown, the Cockroach is great. If you’re in the middle, choose conventional wisdom. Note that these aren’t optimal, they’re just the financial equivalent of choosing the right sport to play. To do anything more is often the work of a lifetime.

Investing has the highest delta between being the benefits to laziness and downsides to medium effort that I’ve ever seen.

But it is true that everyone does it. More than 50% of American households own some mutual funds. Around half own stocks. They all have to decide which funds and which stocks, and so they do. Entertained by CNBC and governed by a combination of instinct and crystallised greed, they do. A third invest in real estate, and the same in bonds. There’s very likely a hell of a lot of overlap amongst those groups, since after all you can only invest if you have money!

But the question that struck me was the same. Considering the number of options we have to invest in, and the dizzying array of ways in which we can do it, the most the interesting question is, why are they choosing to invest their money in this combination of assets? What did we used to do before? How did the people in the 18th and 19th century invest their money, and how did that change?

II. What things looked like

It all started, as most things, a few centuries ago. Back then, if you did have some money, you still did think about the future. It surely didn’t seem to be coming at you at the speed we see today, though arguably people born in the late 1800s should have!

Which meant they invested mainly in assets that generated cash - like real estate or commodity trading businesses. Some households kept their wealth at banks, or invested in government bonds.

The aggregate wealth though shifted since the early 1900s.

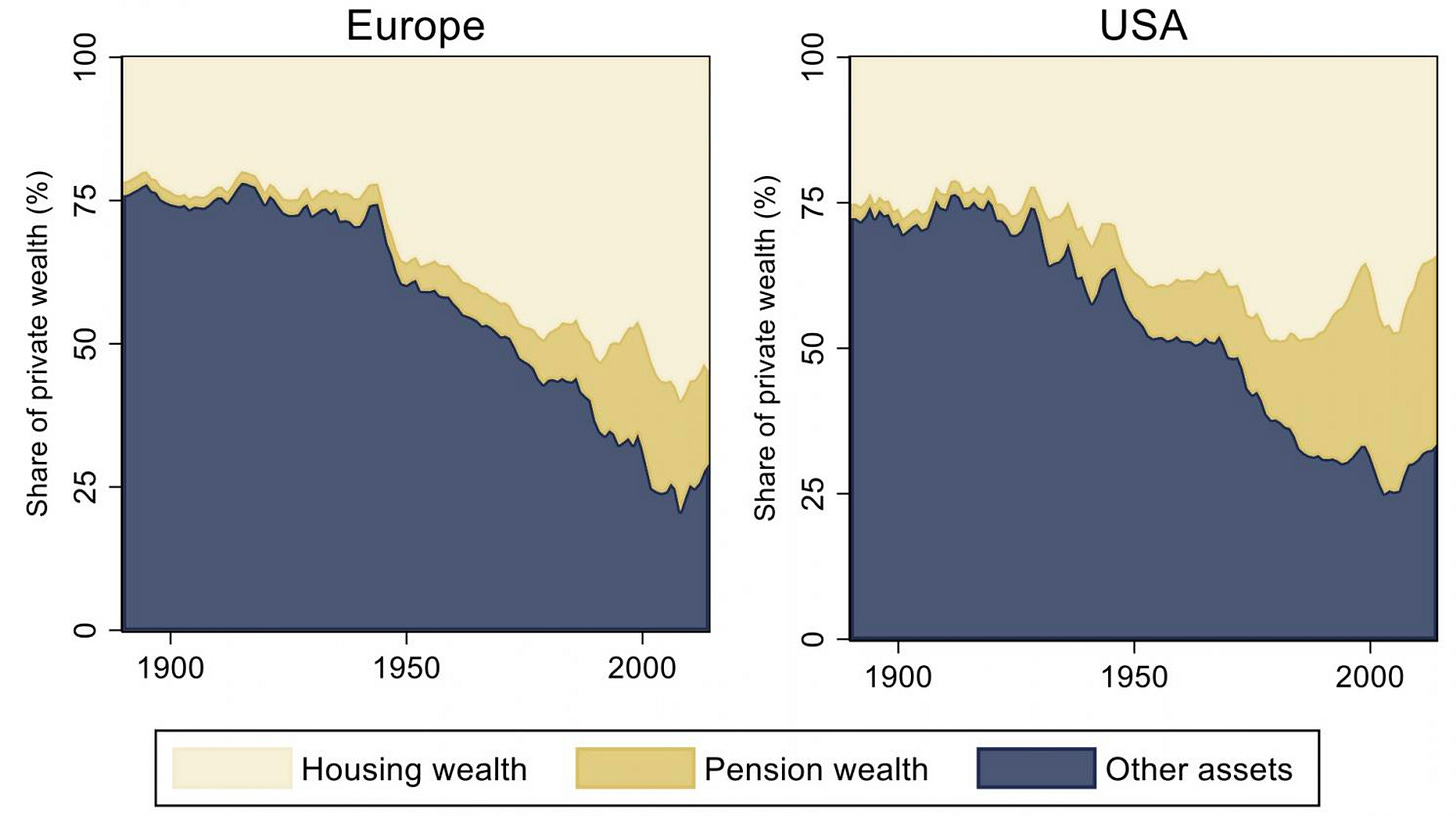

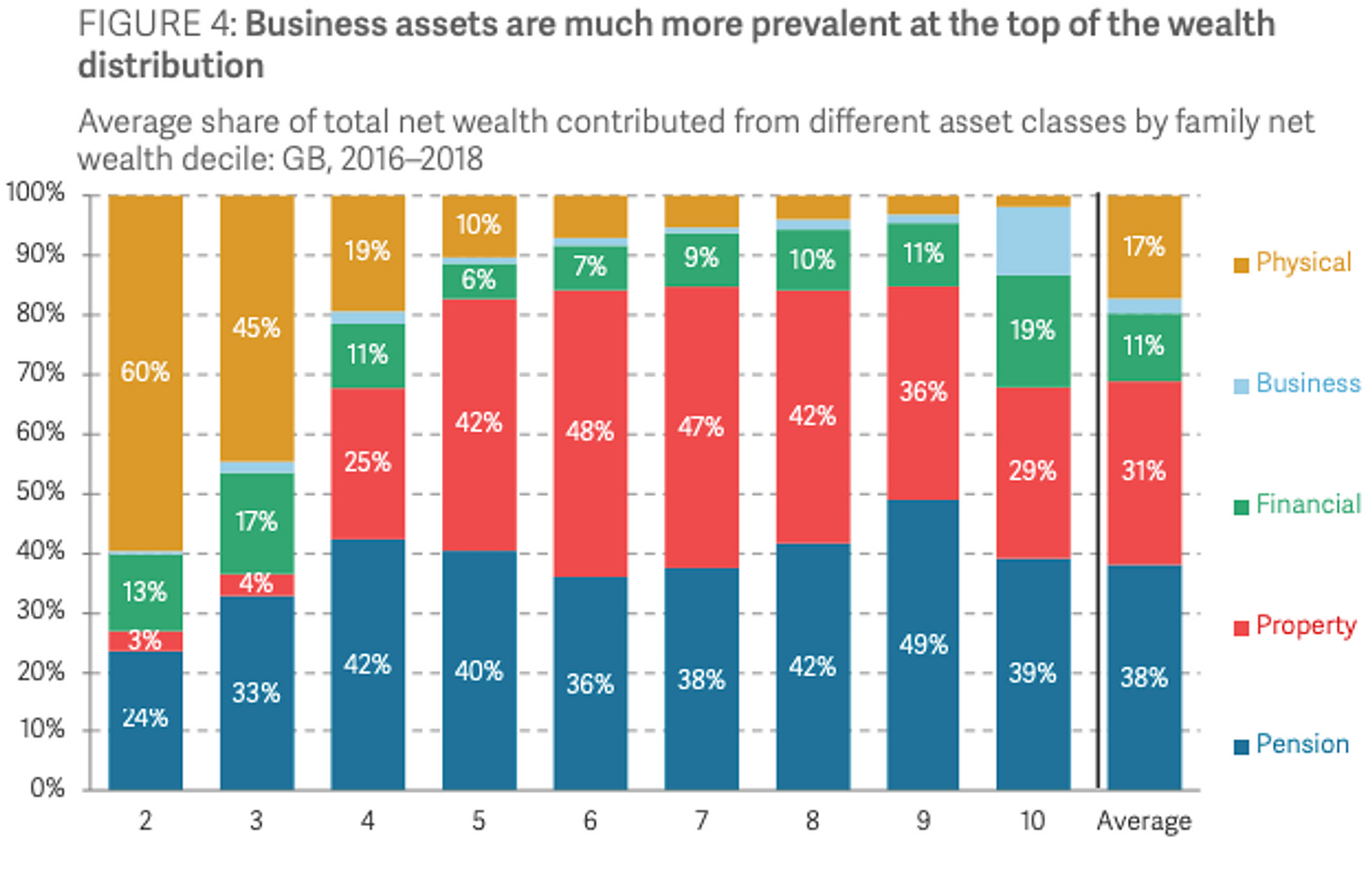

The main result is that private wealth underwent a structural shift over the 20th century. Around 1900, wealth was dominated by agricultural estates and corporate wealth, assets predominantly held by the rich. During the post-war period, wealth accumulation came mainly in housing and funded pensions, which are assets held by ordinary people.

The shares shifting towards housing is an indication also of how more people could have housing wealth, and also that everything rose!

This essay isn’t about wealth inequality though, it’s asking where people invested their extra money.

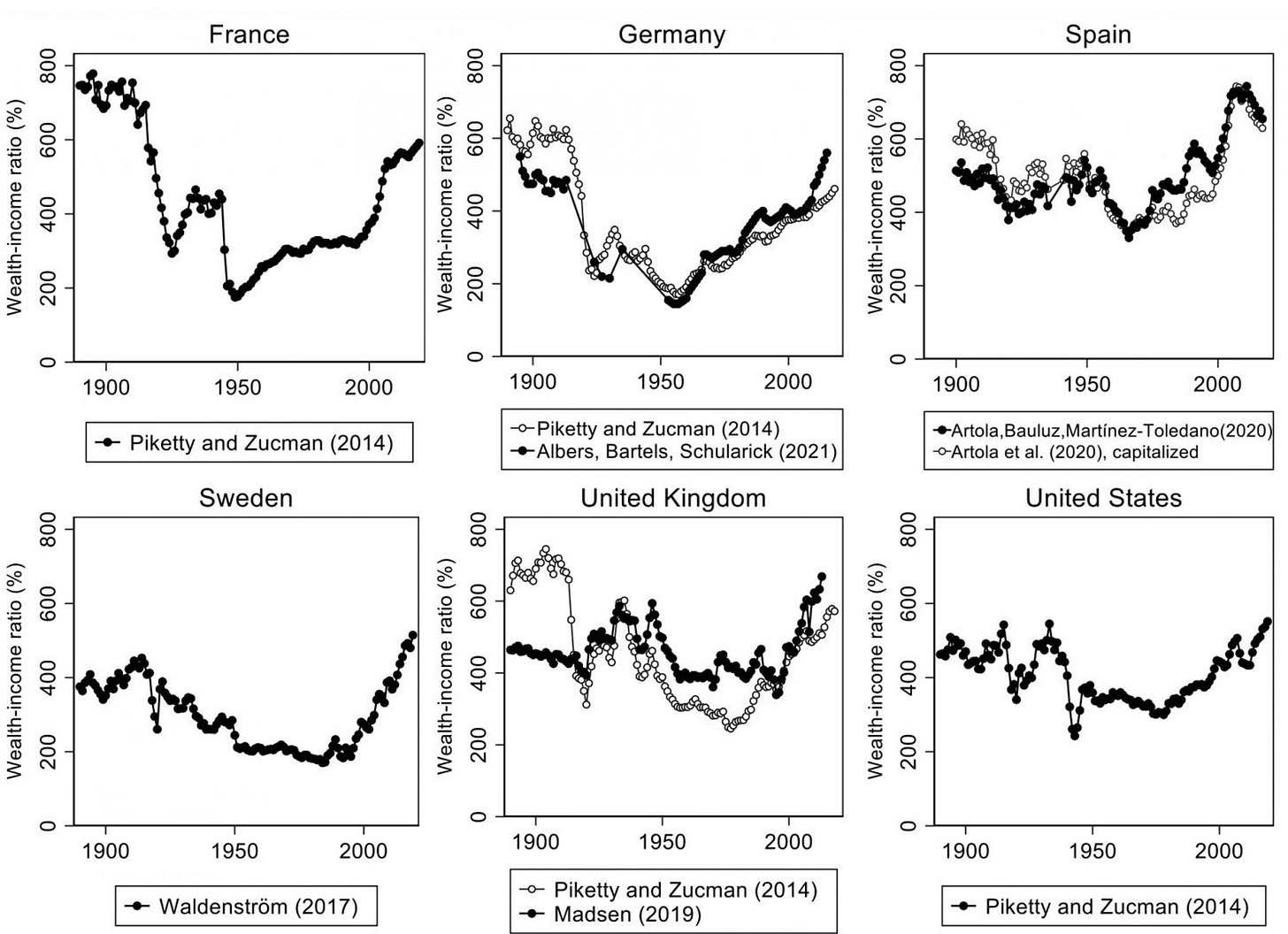

People’s wealth differed from where they got their income. Back in the day, a century ago, people were much wealthier than their incomes would suggest, and in most places it went through a hell of a valley before reaching similar levels by the 21st century.

What is “wealth” though?

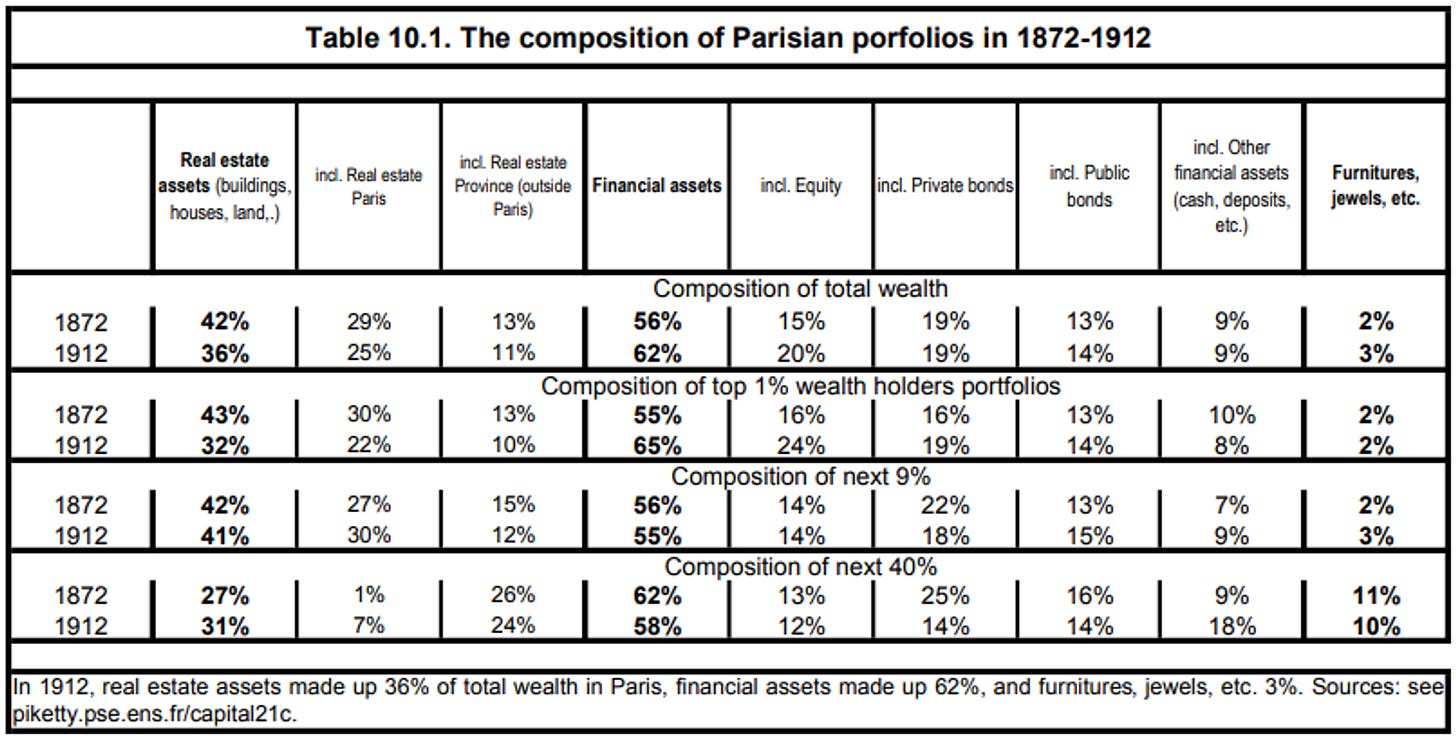

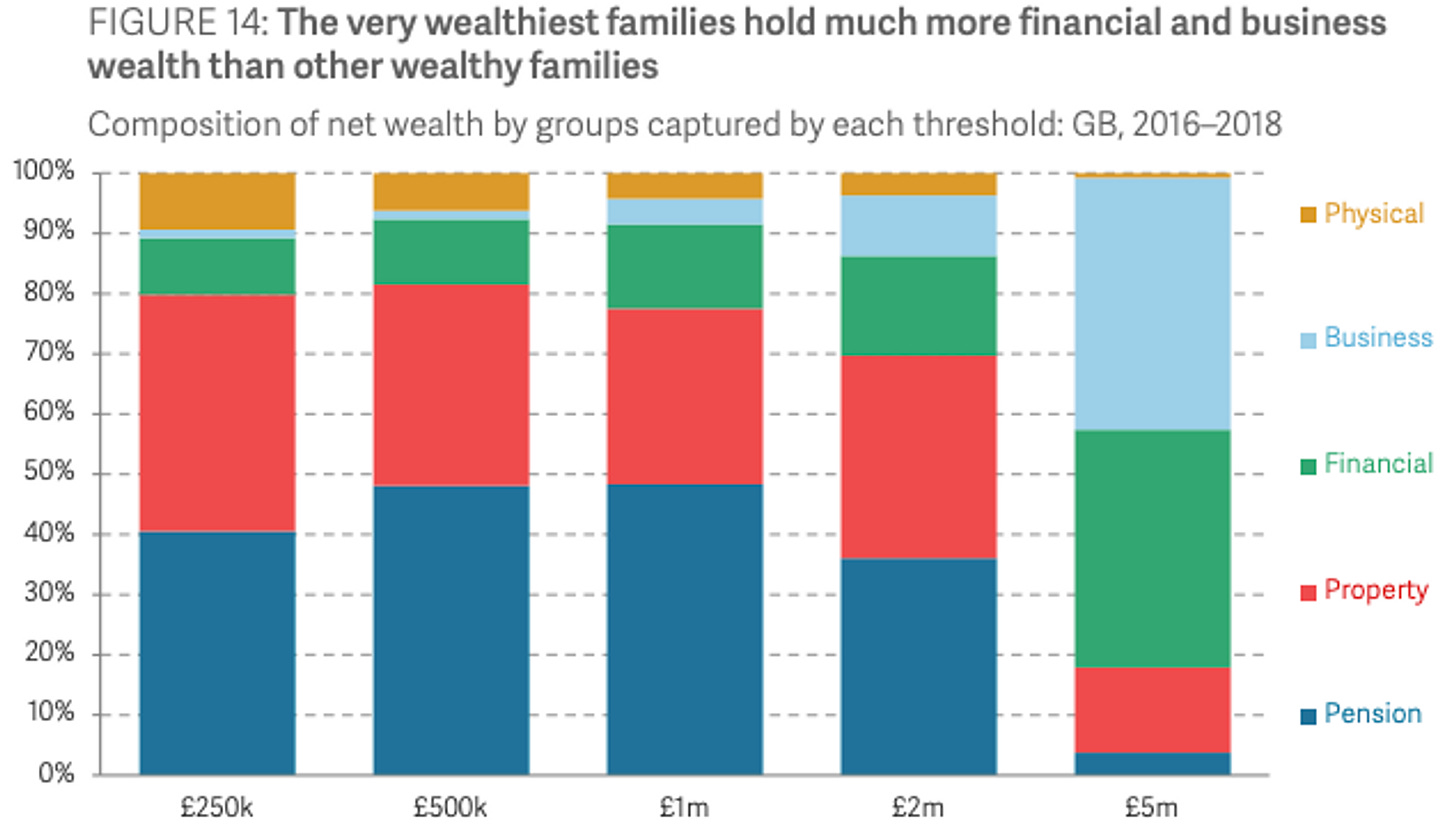

Turns out, Piketty has some data on this. Which shows that for the most part, people’s wealth was pretty much tied up in the land and house they owned, with the rest split between basic financial assets like equity and bonds.

The delta here that struck me is that the richest group here held more of their assets in real estate and less in financial assets (and more in jewellery though that’s not surprising).

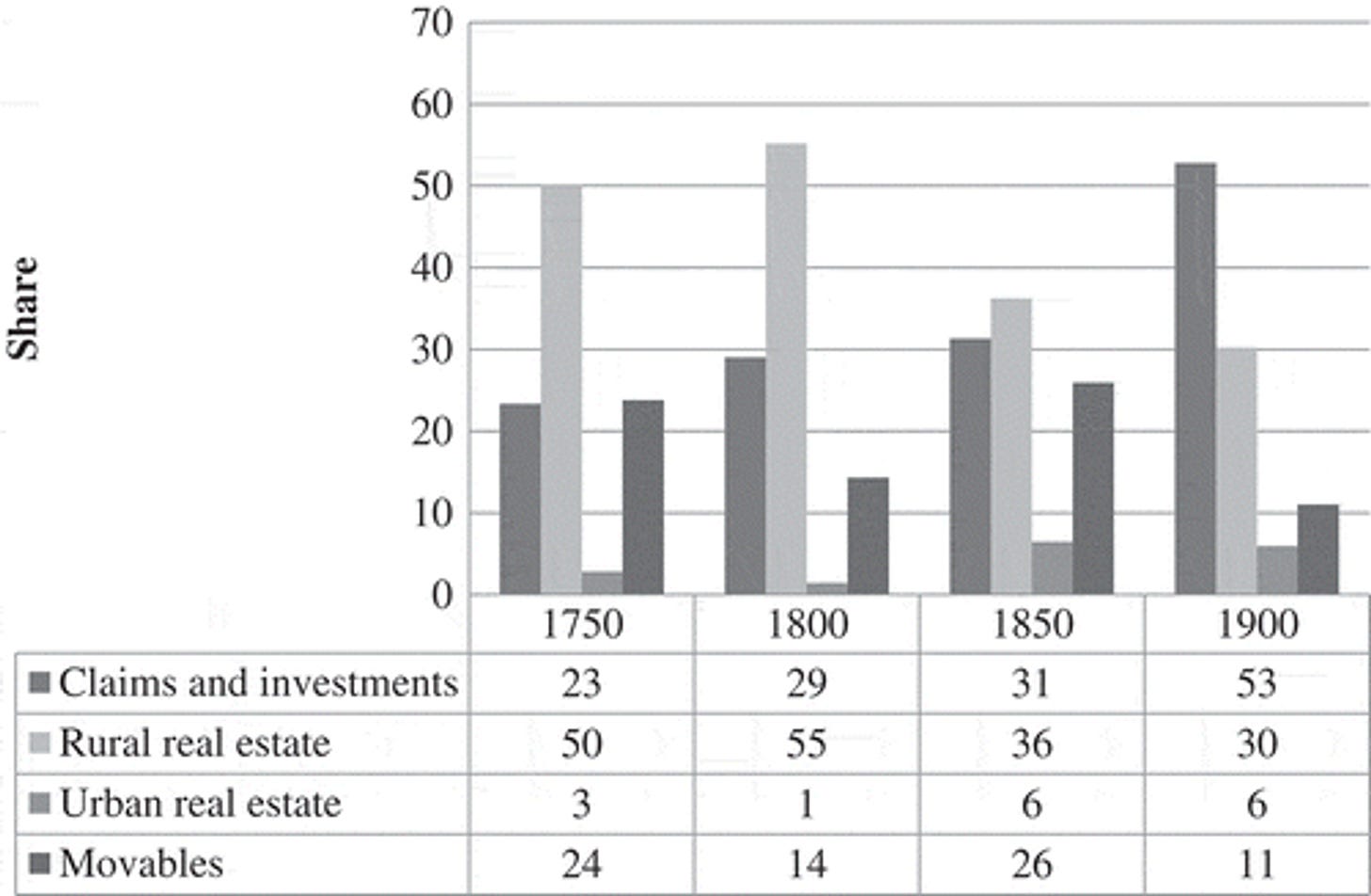

Paris isn’t an outlier. From an analysis of Swedish families

The contrast between these two families is striking; while the the low nobles Freidenfelts held no real estate, but a considerable amount of shares, the high noble Lewenhaupts owned vast landed estates with a mansion, a demesne and tenant farmers. 79 percent of their fortune came from rural real estate, while 92 percent of the Freidenfelts’ fortune came from stocks.

Even between the “high nobles” and “low nobles” there’s a separation in terms of where their wealth actually was.

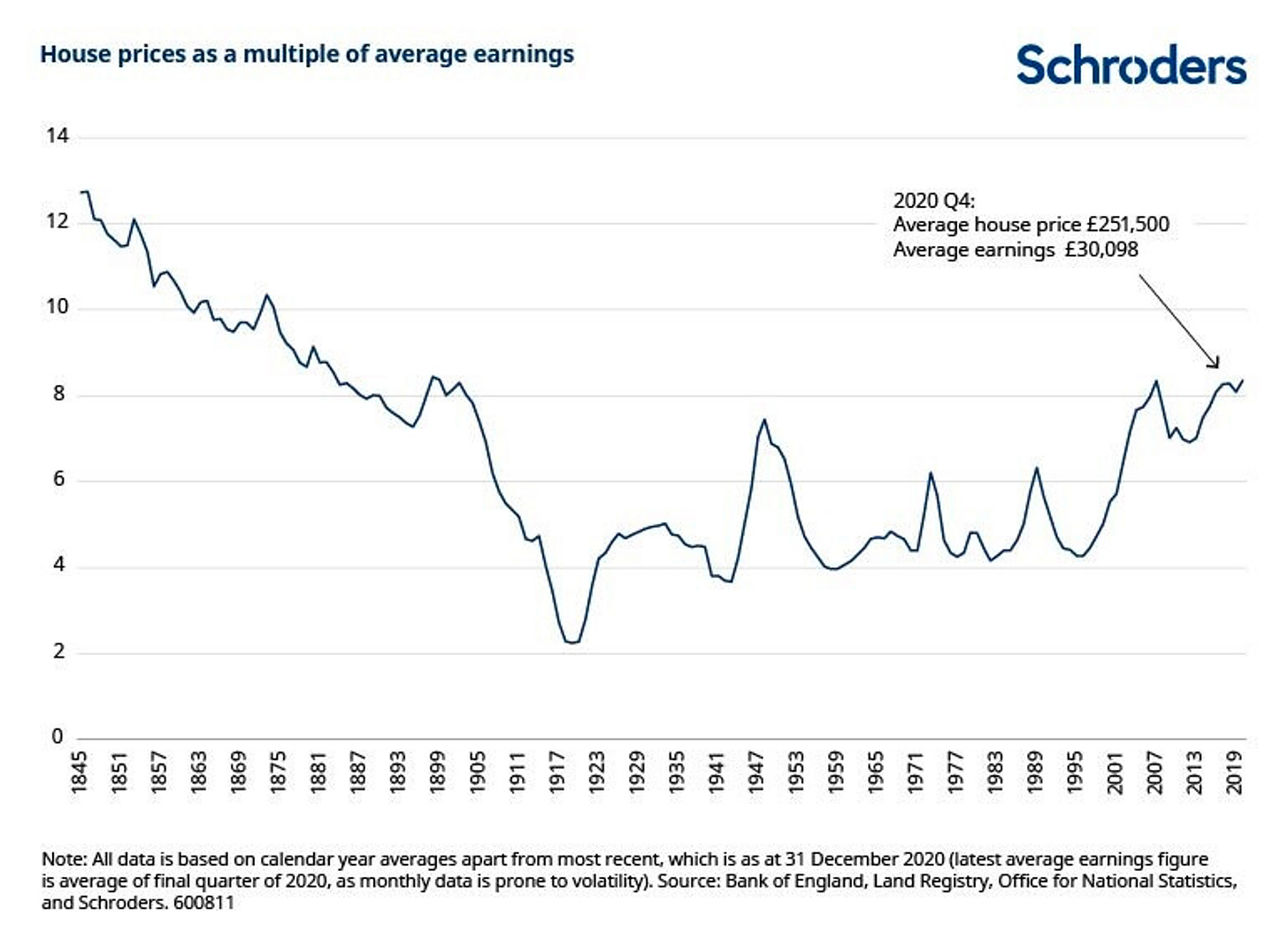

What about real estate, the other most likely option? It seems to have decreased substantially over time in terms of affordability, and only recently climbing back to levels last seen in the late 1800s, when it was defeated by more supply of homes. As homes got more affordable, the percentage of people whose wealth resided in their homes increased!

This has changed a little bit today.

In the 19th century, the wealth was concentrated more in the holdings of businesses and corporations, and land. This too is a change from a couple centuries before this, when wealth mostly meant land and holdings, before the advent of joint-stock corporations.

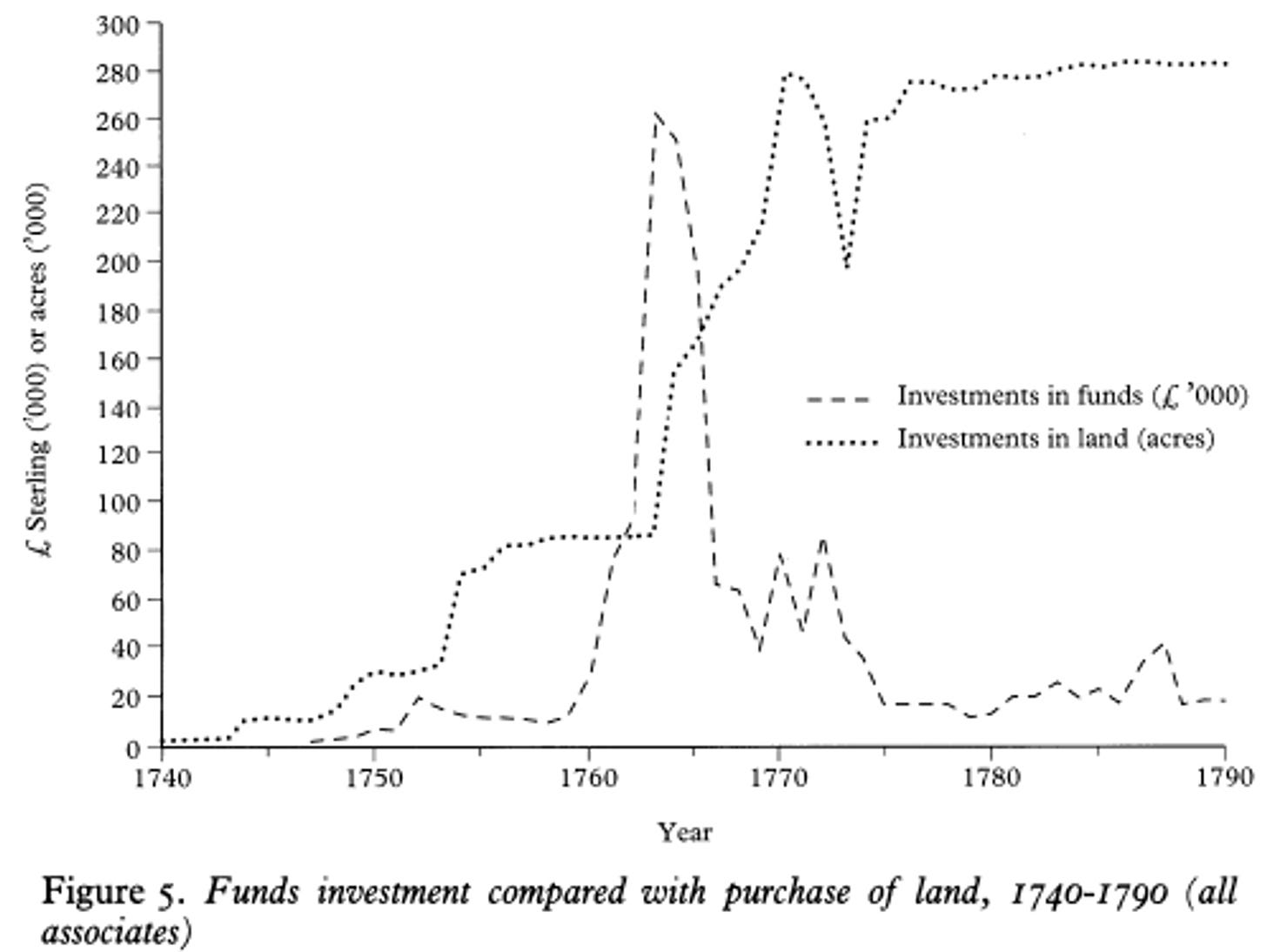

If you had any money, you’d therefore have it in a few company annuities, income producing land and businesses, and perhaps holdings of stocks. As can be seen from the accounts of a few of the monied merchant class - during the great boom times of investing the join-stock funds, like East India Company, Bank of England or South Sea, this is how they invested their cash. From Domestic Bubbling, by David Hancock.

III. Disposable Incomes

Putting it all together, if you had disposable income a century ago, you had few investment options.

Wait for a door to door salesman to come and sell you some corporate bonds

Buy some newfangled equities, especially as they started being easier to buy with exchanges

Buy businesses with cashflow

Buy land (also a business with cashflow)

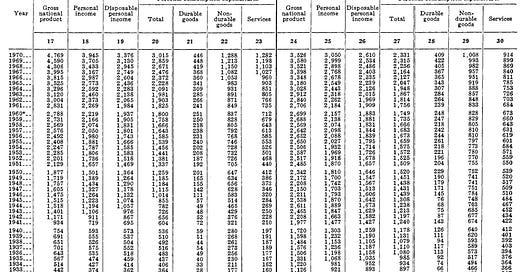

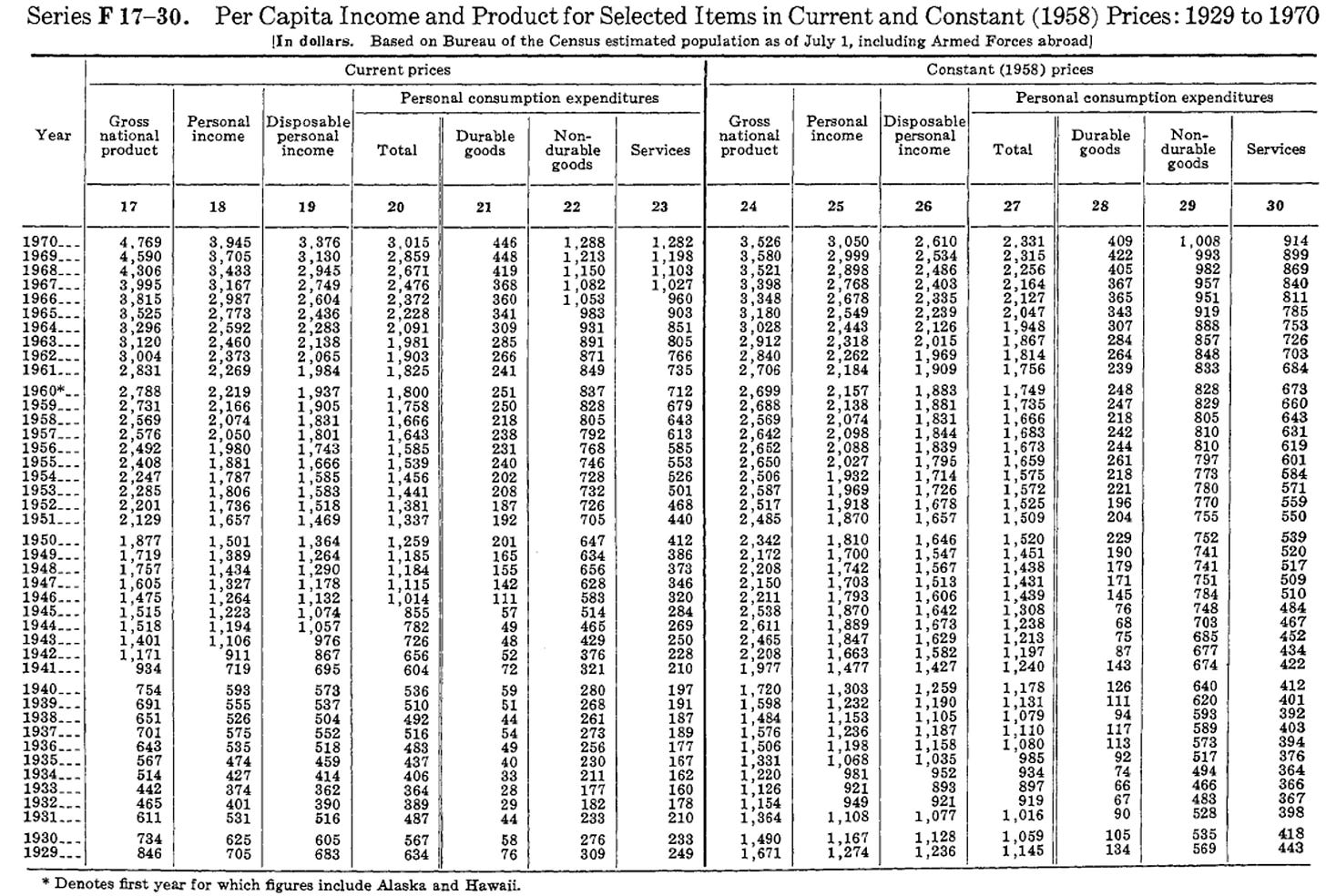

Disposable personal incomes over the past century and half has clearly improved. Compared to the expenses that people had, the savings rate was clearly much lower, the further back you go. The US Census Bureau has fantastic data on this, and a lot of other characteristics, which I found very helpful.

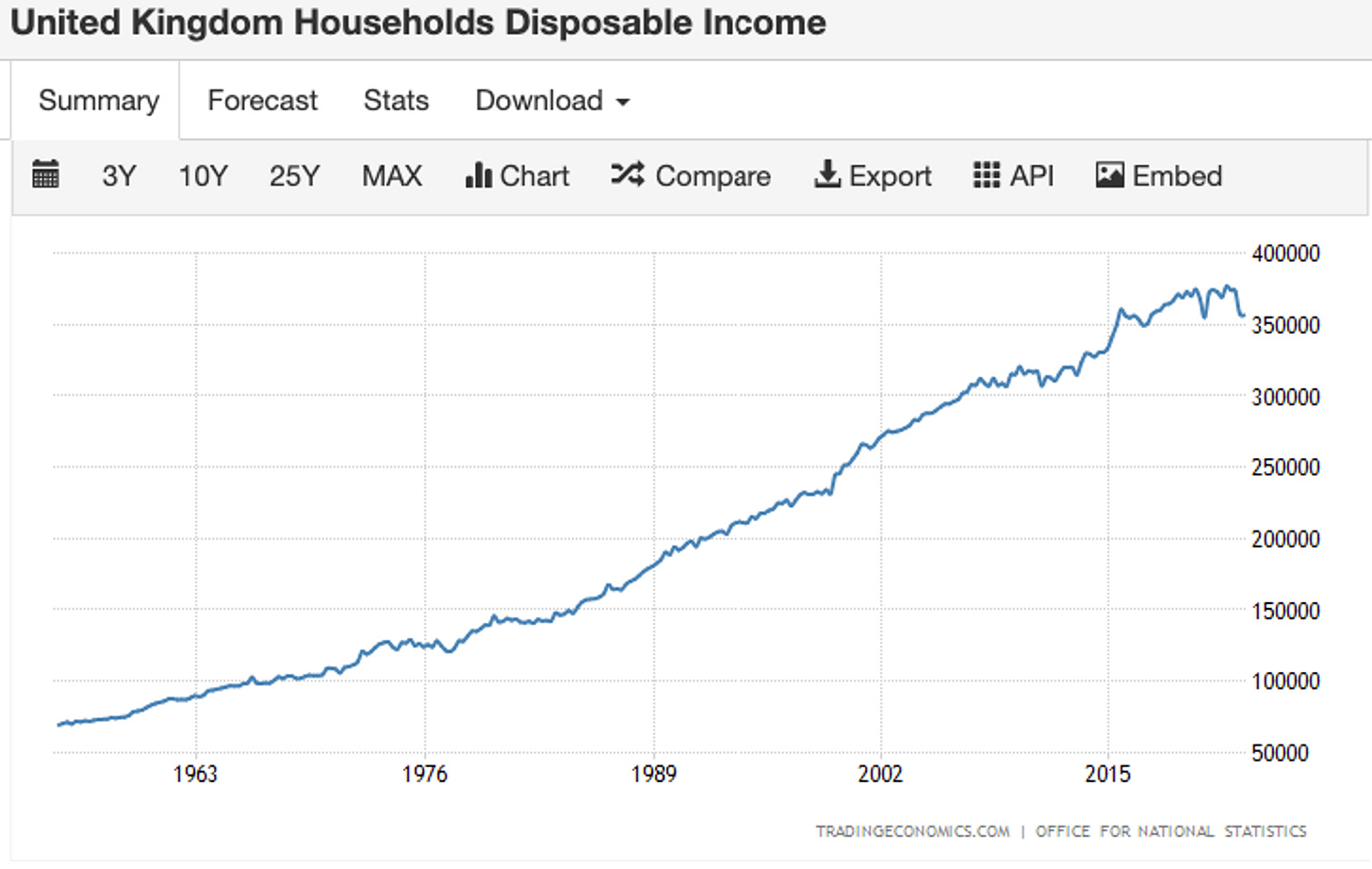

Disposable incomes have skyrocketed in the past half century, as in the half century before.

And the debt service levels, despite the craziness of the world, has been in a relatively tight band. This doesn’t include the complexities of how this is distributed within the population of course, but let’s leave that aside for now, since we’re more interested in the aggregate changes.

IV. So what

What have we seen so far? People didn’t use to have much disposable income to invest a century ago. When they did, or rather those who did, invested their savings mostly in land or (if they were rich enough) businesses, or commodities.

Where should I invest my money is a relatively old question, but until recently it wasn’t a very interesting question. This is because until recently the answers were understood, but not that actionable. The futures would get better, things would get built, and you could ride optimism as a thesis if you could find a way how. The avenues available were extremely limited, and the optionality you had was minimal.

Even though there were investment crazes that people ran behind, from the Tulip mania in the Dutch Republic to Railway mania in the UK, from the South Sea Bubble to the Mississippi Company.

Some of these, like the South Sea Bubble, did supposedly attract tens of thousands of people, including shopkeepers, farmers, and labourers, who invested their savings in the company only to see it evaporate.

The Transfer Ledgers record roughly 7,000 transfers during 1720, while the Ledger Books from 1720-25 record over 8,000 individuals holding stock. The analysis finds the customer base had breadth and depth, comprising individuals from across the social spectrum, from all over England and Europe. The market was diverse and liquid. Activity during the Bubble came from those living in and around London, with most traders participating in the market only twice at most.

(Also, as an aside, if you did a gender cut on the South Sea Bubble men as a group lost money and women as a group made money. I find this an interesting historical curio.)

Of course, these were pretty hard to do, since most of the sales were over the counter and not through a centralised exchange. But even then tens of thousands of people who had some money left over managed to find a way to speculate to try and make themselves richer.

But as the trends in disposable income changed, and people got more money to save or consume or invest, they did all three. The savings rate, which has mostly been fluctuating around high single digits since the 50s, rose from 16% to 22% between 1830 and 1900.

Money was backed by gold in those days, which made investing their money in gold one of the safer options for most folks even though the returns were terrible.

To take an extreme example [of price volatility], while a dollar invested in bonds in 1801 would be worth nearly a thousand dollars by 1998, a dollar invested in stocks that same year would be worth more than half a million dollars in real terms. Meanwhile, a dollar invested in gold in 1801 would by 1998 be worth just 78 cents.

V. Invest in the future you know

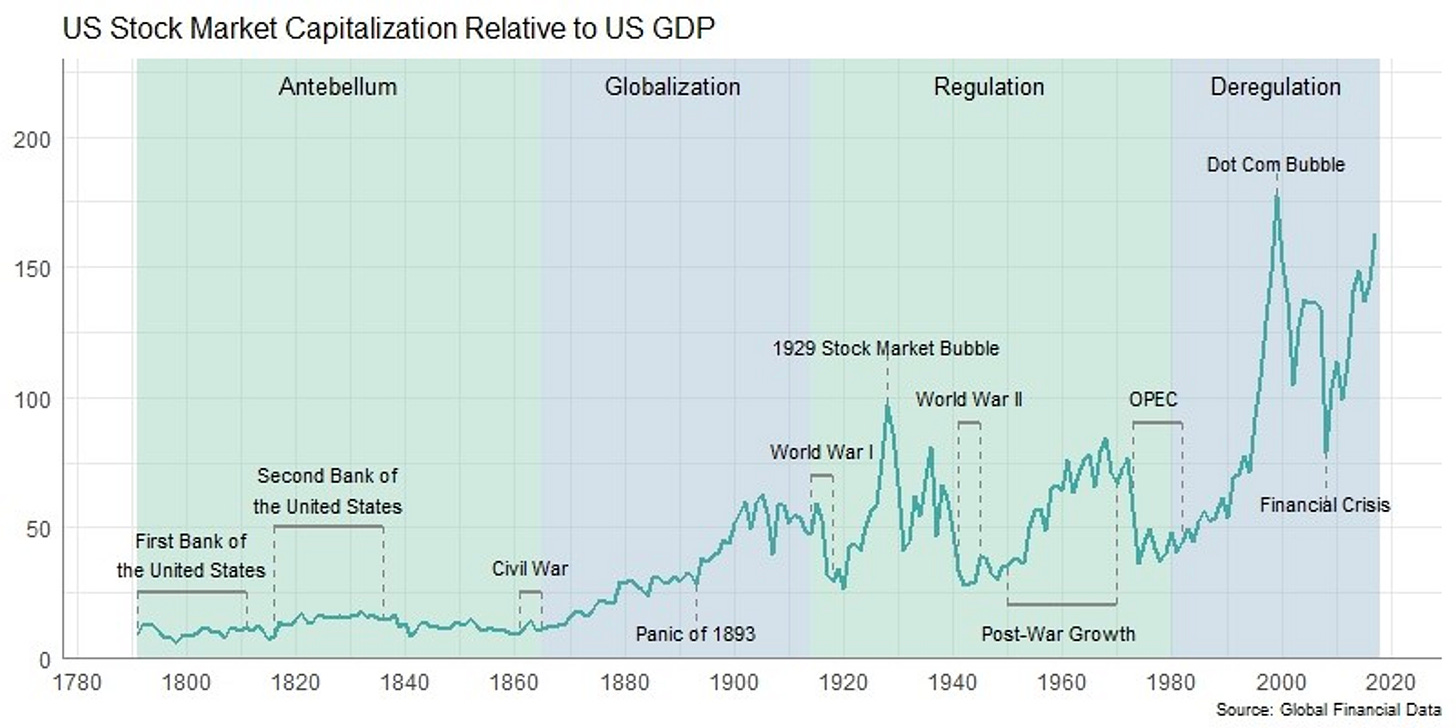

The details of how the world of investments changed is detailed very well in the book Investment: A History, by Norton Reamer. In the late 1700s, there were just 60,000 holders of British government debt, just over 1% of the population, and much fewer joint-stock company shareholders though equity was more attractive. Even in the 20th century, after the NYSE was set up, most of the retail trades were through bucket shops, set up to speculate on the direction a stock would trade (like CFDs today). A form of gambling, not investing.

Sometimes I think we forget that regular people investing in the markets is a relatively recent phenomenon.

In the good old days, when you could invest, you did it in the future you could see - lands being conquered, businesses being built, trade. These days we're much further removed from the action, and need to define our own vision.

The first stock exchange was established in Philadelphia in 1790.

The 1800s saw a massive increase in people’s excitement about buying shares in new businesses, specifically railroads. They flocked in and created booms and busts, but still in pretty small percentages, since most people didn’t have money and there was no easy way to trade!

Later, in the 1900s, excessive exuberance gave way to the Great Depression in the 30s, leading to increased regulation of the market and the creation of the Securities and Exchange Commission in 1934.

Mutual funds and pension plans grew in the 60s and 70s to bring even more people into the market, since they could now invest in bonds etc much more easily.

Then came the discount brokers in the 80s and 90s, where the “discount” in the name stood for “not as expensive as before”, making it cheaper than before to buy and sell stocks. And making it cheaper did drive the volume up!

Then came online trading, and perhaps not coincidentally even more rampant speculation including the dot-com bubble. But it did bring more people into the markets.

And latest, we had the rise of fee-free trading platforms and ETFs, simultaneously democratising the most active (daytrading) and most passive (ETFs) parts of the market.

The world we see around us, including the assets we can buy, all had their histories. Stocks were newfangled four centuries ago, and was hard to buy even a century ago. We had annuities and merchants bought bonds, but it wasn’t a retail instrument until much much later. Mutual funds and pensions brought investing to a whole new slew of people who looked at investments in them as investments in their future. And the rise of ETFs and ability to trade without fees brings a whole new group who can skip from treasury bonds to gold to bitcoin, with ease.

The revolution has brought ease to the process and clarity to the instruments, but the hard part is still knowing what to do. There’s no shortcut to figuring out what you believe and actually translating it in the market.

That’s why knowing the history is important. Because there was a time when nobody thought buying equity was particularly important. Same for multiple varieties of corporate bonds. Same for commodities that aren’t gold for that matter, which some people still contest! How people used to invest in the days when the stock market was immature is also a bet on a particular future.

Today, we have stock market: GDP ratio of >100%. We have slick instruments to trade gold and oil and platinum and silver. We have the ability to buy bonds and actively managed mutual funds and sectoral ETFs and crypto tokens and, if you’re rich enough, slices of private companies or have fun with derivatives.

You still have to answer the question though. What do you think will change, and what will stay the same?

As more people have been introduced to the markets, we've reduced the costs of their ability to enter. Higher the demand, lower the cost, in a technological loop. As more retail investors have gotten in the game, government entered it too to protect them.

And as the size of the pot grew, people banded together to try and win, institutionalising all aspects of participating in the market. And the latest move to bring more people into the market has been to move away from active to passive investing. And now, I bet, to the rise of better standardisation, so we know what the instruments we've devised actually do.

Appendix

Here’s something that is pretty incredible. Did you know the market cap of the entire U.S. stock market in 1990 was only $2.8 trillion? That’s what one company, Apple, is worth today.

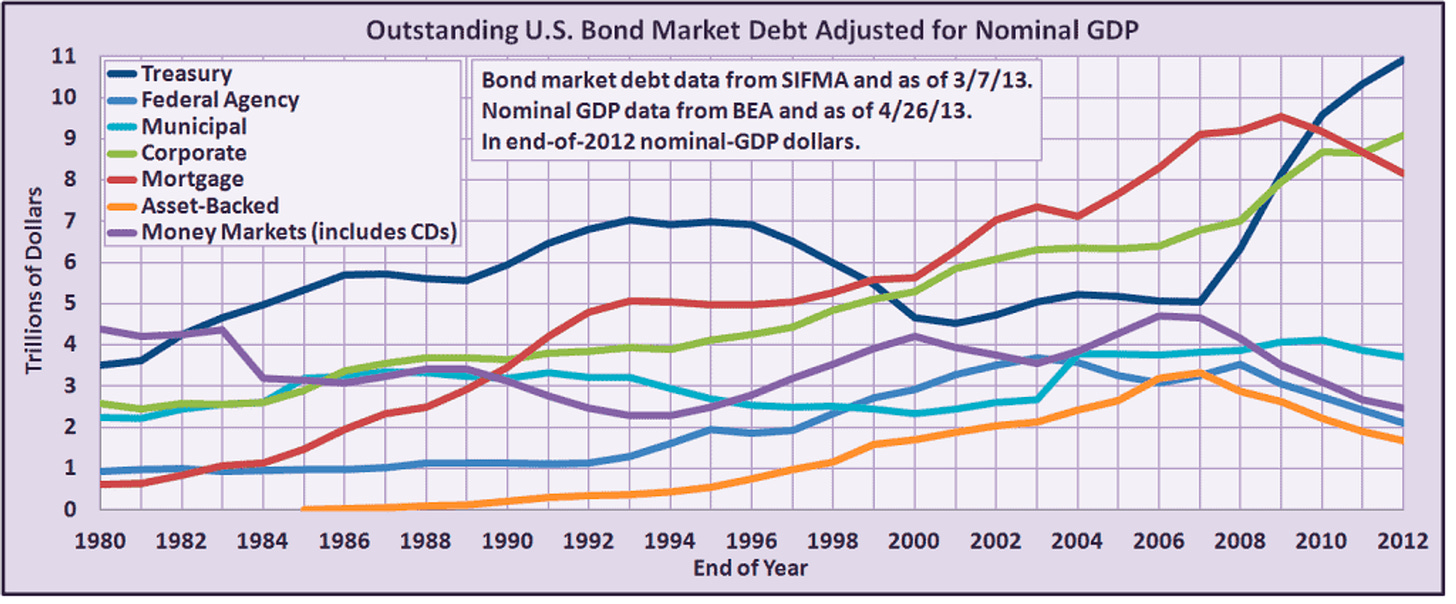

Same for the Bond market, which is around 10x the size of the stock market. It grew first through railroads, and later through corporate issuances.

Between 1850 and the early 1900's, railroad company bonds dominated the corporate debt market. .. At the same time, an expanding number of public utilities and industrial corporations were also issuing bonds. Between 1900 and our entry into World War I, corporate debt tripled from $6 billion to over $19 billion – exceeding the federal debt.

Very well done. A nice article.

This was a fun jaunt through history, thanks for doing the digging and laying it out so neatly!