Progress as cluster creation

How clusters seem to permeate the history of innovation and take primacy over both individuals and ideas

I

The survival rate for startups is around 10%. But there are a lot of companies and maybe there's an adverse selection bias. After all, most people fail at the things they suck at. But survival rates for venture backed startups is 25%. It's better, but considering venture backed startups have convinced someone else to give them their money too, this still seems low.

The overwhelming majority of them fail because what they thought to build didn't make a dent in the actual world. For every Zuckerberg, there are thousands of failures.

So against these seemingly crazy odds, why would anyone start anything? Because they see a large enough prize to make the expected value positive. One way is to make the eventual end prize massive. That's where the silicon valley startups play. If you even have a 1% chance of making $100m, that's worth $1m. Surely you should take the shot if your alternative is $200k in a cushy but boring job. What about the guy starting a video store down the road in the year 2020? Because the alternative isn't all that great there either. It could be a labour of love, but that's usually not very economic either.

And yet, progress depends on finding a few more of those Zuckerbergs That would sure be helpful. If we rely on individual actions to act as step functions in our progress ideal, then after all it makes sense for there to be many instead of just one.

II

The problem with things that are stacked according to a power law is that wishing the top of the distribution was wider can't make it so. And the distribution of top performers is most definitely a power law, in economics, politics, even sciences. The only realistic option is to expand the whole distribution.

The problem with expanding the whole distribution is more straightforward. Any program that promotes it will have to be far more okay with failure.

As a technology investor the hardest part of my job is that I have to build conviction while investing in every company, even as I know that most of them will not be my eventual 'winner'.

So how do you invest at all when you know most of your investments will fail? Like the old joke about the porcupines mating goes, carefully.

Peter Thiel likes to say that this power law of returns means there's only one rule of investing, only invest in those ideas which can provide outsized returns. Which sounds like a smart idea until you realise, if you could do that anyway then the problem wouldn't exist.

The story of Airbnb, far before it broke the back of the hospitality industry, is that the founders had to sell presidential candidate themed fruit loops to raise money to keep their company going. Share a mattress in your house with a stranger? Yeah sounds exactly like a winner. Paul Graham writes:

If you look at the way successful founders have had their ideas, it's generally the result of some external stimulus hitting a prepared mind. Bill Gates and Paul Allen hear about the Altair and think "I bet we could write a Basic interpreter for it." Drew Houston realizes he's forgotten his USB stick and thinks "I really need to make my files live online." Lots of people heard about the Altair. Lots forgot USB sticks. The reason those stimuli caused those founders to start companies was that their experiences had prepared them to notice the opportunities they represented.

So how do you promote more Zuckerbergs. You can't tell which ideas would succeed, and often the ones that do are weird and unremarkable at first. If you look at the top VCs and their successes in backing the most amazing entrepreneurs you see a pattern. They've all been successful at backing some of the biggest names - Microsoft, Intel, Google, Apple, Salesforce, Uber, Facebook and so on. But the more interesting thing is the anti portfolio. Only Bessemer are brave enough to put it up, but they have all said no to a larger group of some of the most amazing companies in the world too.

What does this mean?

That people who do this for a living, and are at the top of their game measured by any metric, who have maintained that lead over decades, still make tons of mistakes.

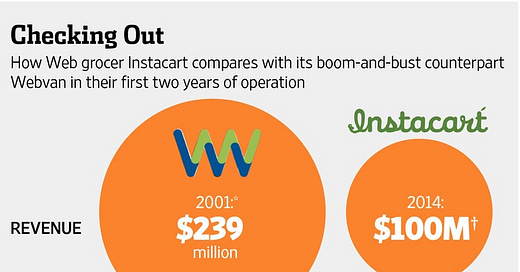

One question is what makes the ones that work stand out. The accepted wisdom is that great ideas can't sound obvious in foresight, only in hindsight, for itself rather obvious efficient market reasons. If it sounds like a good idea then someone would've done it already. But I'm not sure that always applies. Webvan collapsed trying to get you groceries. The same idea today works evidenced by Instacart. Despite raising around the same amount of money, and trying for relatively similar business models, save a pivot or two, one died while another thrived.

It could be that you have to wait for the market to come to you, and that's a perfectly fair answer. But it also means that you can't rely on an idea to do the heavy lifting. You need the idea + the market to be ready to accept that idea + the world to provide you with the relevant infrastructure to execute the idea (you need fast internet and easy tracking and so on and on).

III

There's a mythology about Hungarian super geniuses who were born at the turn of the 20th century, all in a suspiciously small neighbourhood, often going to similar or the same schools, and growing up with each other. John von Neumann, Paul Erdos, Leo Szilard, Edward Teller, Nicholas Kurti, Peter Lax, Nicholas Kaldor, George Soros, Andy Grove, Dennis Gabor, George Polya, the list goes on and on. They towered over fields of mathematics, physics, chemistry, biology, economics, computer science, even business. There's barely a human endeavour where they did not make a large and towering difference.

So there are three possibilities. One is that Hungary at the turn of the 20th century was hit with some sort of genius radiation causing a genetic mutation in a large fraction of the population, and hey presto, genius alert. It's unlikely, of course, but what else could explain the extraordinary co-location of such a large number of geniuses who were all so good, that they got to the top of their fields.

Another option is that they were all pretty bright, but something in the cultural zeitgeist combined with some special educational process or insight created their special abilities. Like Professor Xavier's school for gifted children, they created superheroes. The puzzle here is what made it stop. Surely if you make superheroes for a couple of decades, you don't stop. You keep going! But it doesn't feel like Hungary is particularly adept today at creating more von Neumanns.

A third option, a more prosaic one, is that when a large number of geniuses encounter each other, they make each other succeed. Let's assume everyone has X% chance of becoming a verified genius. And as soon as one of them became recognised he would pull the rest up as well, if nothing else through sheer osmosis. If you write a great paper about an idea you had, it would receive a lot of attention if your best friend was a Nobel prize winner. The feedback loop that makes your idea better is tighter, faster and way more potent. It might not impact everyone, but the cluster you're a part of makes all of you succeed far more than you would individually.

You see the same thing in history. Wherever there was a large enough cultural shift to create history-changing momentum, there usually was a large enough cluster. Ancient Greece, The Renaissance, Industrial Revolution. This isn't true of all cultural superiority or dominance, but it's oddly prevalent in areas where individual outperformance pushed human thought forward. The modern day silicon valley and Israel are said to be the new centers of excellence too, though their influence on art or science has as of yet been rather muted. Israel is small enough that there's enough overlap amongst all parties, and they do sport an impressive Nobel prize to population ratio. But the real export at least from the valley has been it's startups, dominating business and it's new explorations globally.

And within this group of geniuses who have all found each other and exchange ideas to cross-pollinate and create even better ones, another constraint is needed. They need to have the right toolkit and ideas in the first place. In Ancient Greece, in the absence of much scientific progress, the advances were mostly made amongst subjects that can be done solely in the mind - philosophy and mathematics. Though we don't know the names, I imagine there would have been similar cliques in architecture in Ancient Rome, or Egypt for that matter. In the Renaissance, they could build on the knowledge that had existed on arts and architecture to sculpt Pieta or build the Pantheon. In Central Europe in the late 19th century there were pressing problems in physics and chemistry which were opening up entire vistas of knowledge.

So the requirements become larger numbers of smart people, who have the time to cogitate and work on things that go beyond their daily bread, connected in networks that enable them all to rise together, rather than just succeed individually. That still seems like something that could exist, and did exist, at multiple points in human history. In almost any society there is an upper class which has enough smart people with enough free time and who know each other from educational and social circles, that this criterion gets filled.

So there has to be something more, something that defines not just their ability to work on something, but the ability to actually make progress on something. I could work half a century on anti-gravity with other smart people, but I wouldn't place a bet on my ability to succeed in floating serenely above the clouds. Some things are harder than just to be a function (talent, time to work, network). It also needs the variable that is feasibility of making progress.

Which means that it's not just that there was a vast sea of ignorance that the geniuses could try to work on together, each guided by their own idiosyncratic likes and viewpoints. It's that oftentimes there existed translucent and tenuous maps that showed potential routes to actually conquer these fields. It's not that Heraclitus had a brainwave that atoms could exist. It's that Bohr created an actual model of what that might look like, and devised experiments to get to the bottom of the matter. Sometimes fields get to a pregnant stage where everyone gets really sure that if they just work hard enough they will uncover all sorts of things. Sometimes they're right, and other times they are not. But the feeling is still there, and it's rather unmistakeable.

So is the right question how to recreate silicon valley? That's been a project theorised by millions and where governments have sunk billions to limited avail. One difference in this culture compared to the ones that came before was in how open to external influences and people it was. Unlike the high schools of Hungary, these were places where those much later in life could come and join too. Did that make it too fragile? It doesn't feel like it. Even now most of the critiques revolve around the cost of living, and not that the idea factory has been closed for business.

The mythology we have in our minds of the lone genius or crystallised insight that falls into our minds is deceptive. The epiphenomena from the larger event within which we live makes

If the initial question was how can we get more Zuckerbergs and we end up with how do we make more silicon valleys that include more people like Zuckerberg, Page and Brin, we've just replaced one tough problem with its equally difficult analogue. Powerful people have always interacted with other powerful people, some of whom would have been influential in other arenas. So it only makes sense for there to be a tighter network that links the geniuses together.

Building a tight network seems somehow like an equally impossible problem, if not for the fact that through serendipitous happenstance we have done it several times as a species. It requires a large enough number of nodes that they can be sufficiently tightly linked, and a strong enough discovery mechanism that the nodes get linked together through edges.

So part of the precondition is that you need a large enough concentration of talent. In most of the societies we discussed, talent was a large enough proportion of the populace that they stood out. Partly signalling, and partly an identification marker saying 'this person is like me', the distinction is important.

What that means is that our job in a society isn't necessarily to prompt getting more individual geniuses, or even to try and foster them through education or similar activities (at the margins), but rather to make the linking of people together easier.

That means encouraging experimentation, encouraging mobility (social, cultural, intellectual and physical), and encouraging interactions. It's like creating an experiment in the Large Hadron Collider, you can't predict which particles will collide where or how, but you can increase the chances of it happening.