Rising complexity and specialised paths to progress

How hyperspecialisation creates efficiency, reduces autonomy and increases polarisation

[Part of an ongoing series - one, two, three, four, five, six]

I

In part I we kind of took a look at how everything costs way more than it should, how some companies seem to be making all the money in the world, and some people are getting most of the benefit of that money. The distributional anomaly we saw was front and center in creating a bimodal distribution in everything. This rising polarisation is partly because everyone knows where everyone else sits in most ideological spectrums. In politics, that clarity makes it harder to defect from pre-established and staked-out positions and also makes it harder to achieve compromise, since doing that is the equivalent of creating a new platform, one that's a combination of multiple viewpoints, which is cognitively more demanding.

One of the most clear articulations of progress in the past three decades though has come from the telecommunications sector. There has been an unrelenting series of hardware and software innovations, which have together disintegrated the barriers to communication across geographic boundaries.

This is undeniably a good thing. Anyone (mostly), at any time (mostly), at any place (mostly), can know any thing (mostly), and communicate that to any one else (mostly). It's a rather magnificent achievement. The benefits are clear. Who wouldn't want to get their news instantaneously? Even those that say they don't want to actually don't mean they don't want to get news immediately, just that they don't want to get all their news immediately.

But the downside is less well examined. What did we lose when we lost our ignorance?

An aside. Close to half a century ago, when my father first took up his job in a public sector bank in a socialist country, the working culture was a little different. Some were large and glaring and obvious - one of my weirder memories of childhood is that he would call his bosses 'Sir' on the phone, and his underlings would call him Sir. In the egalitarian mind of a teenager this was anathema, especially since as far as I knew my dad wasn’t an OBE.

This wasn't just some weird personal quirk. When I turned thirty, long after the story would've actually been useful, I heard the story of how my dad had always wanted to join the Navy. He apparently studied hard and worked out like crazy to get into the right mental and physical shape to pass the tests. And in the process of taking the train to go to the interview, he fell asleep and missed it. I have never felt more closer to my dad than when I heard that!

But there was another part of the job that I only realised was a part of a bygone era only once I started working. He had joined a highly bureaucratic organisation at a time when being highly bureaucratic was seen as a virtue (see public sector banking in India in the 70s). One of my other memories of going to his office as a kid was giant piles of paper and files that always smelled musty. However soon as he got promoted to be a branch manager, he effectively had his own fiefdom and was his own master. For most of the time and for most of his career, the responsibilities and the size of the branch and the amount of deposits and loans he could handle all grew larger and larger, and that was about it.

The interesting thing though was that in his entire career, late 20s onwards, he had substantial amount of autonomy over his work. And not just in principle like "make sure you hit your targets and we don't care about the rest". But "we'll talk with each other maybe twice a year when we can discuss how you hit your targets".

The difference from this and my jobs have not necessarily been the reduction in autonomy, but rather the fact that my relationship with my boss was much more intimate. It had feedback cycles measured in days or a week, and you're always labouring under the knowledge that you're one part of the machine.

And the impact of this is massive. If you want your work to feel like it has meaning, you would want to make sure that you are treated as an adult. Not supervised minute by minute which seems like the worst of the surveillance state, but also the more insidious ways of constantly being on call, tighter feedback loops that try to wring every ounce of efficiency from your work. My former employer, no slouch when it comes to constantly improving their employee productivity themselves, wrote how there needs to be a movement towards providing employees more autonomy in their work as a way to reduce workplace stress and consequent burnout and churn. HBR says similar things, about how only 47% of employees have flexibility in their jobs, while 96% say they would like it. Even though this sounds like a suspiciously loaded question (would you like freedom? what about more money? what about a pony?) the conclusion is inescapable.

Aditya Chakrabortty of the Guardian writes convincingly about how even as we are getting oodles more choice as consumers, as employees this is in reverse.

In 1986 ... 72% of professionals felt they had a great deal of independence in doing their jobs. By 2006, that had plummeted to just 38%.

There are hundreds more examples, but the conclusion is inescapable. In most cases, we are becoming less autonomous in doing our jobs. As for my dad, his modern counterpart will not only have the multiple conveniences of modern banking to help her, such as extraordinary computing power, better underwriting capability, easier customer servicing options etc, he will also be bound by much tighter strictures in terms of what she is actually allowed to do, and where, and how.

II

So why is the tie tied far tighter today vs what it used to be?

One theory is that the old way was just crazy inefficient, with massive amounts of leakage for every type of work imaginable, and the modern way is just the cost of tightening all that up.

Somehow doesn't seem very compelling.

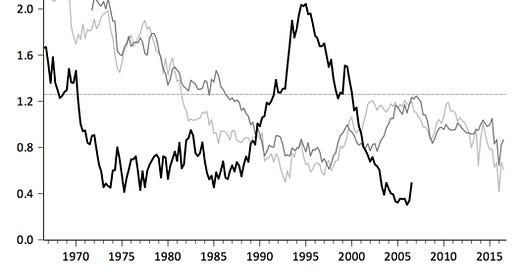

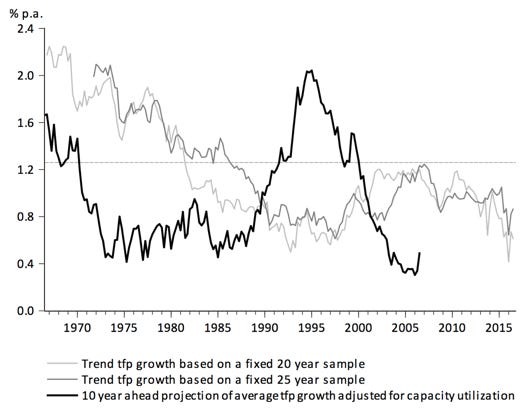

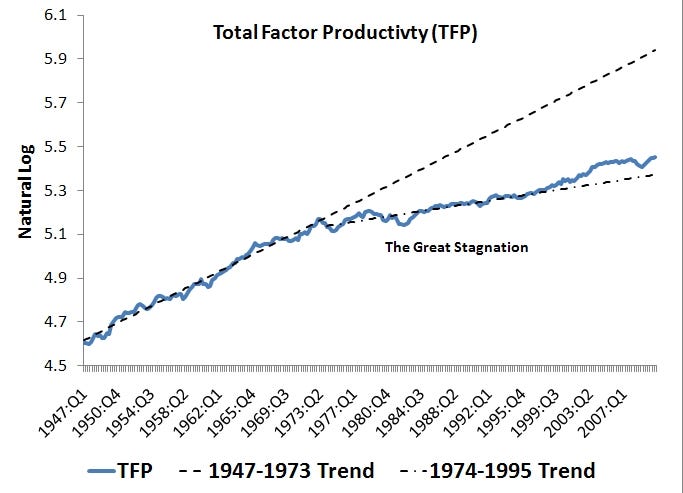

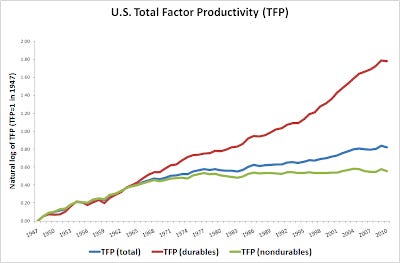

We can probably look a bit deeper to understand which parts of the economy is actually stagnating, as Mark Thoma has done. Looking at the numbers it looks like its the nondurables which drags it down. Durables, which include most electronics, has continued its climb, happily ensconced in Moore's Law, while nondurables, which include food and clothing but also all sorts of services, has flattened.

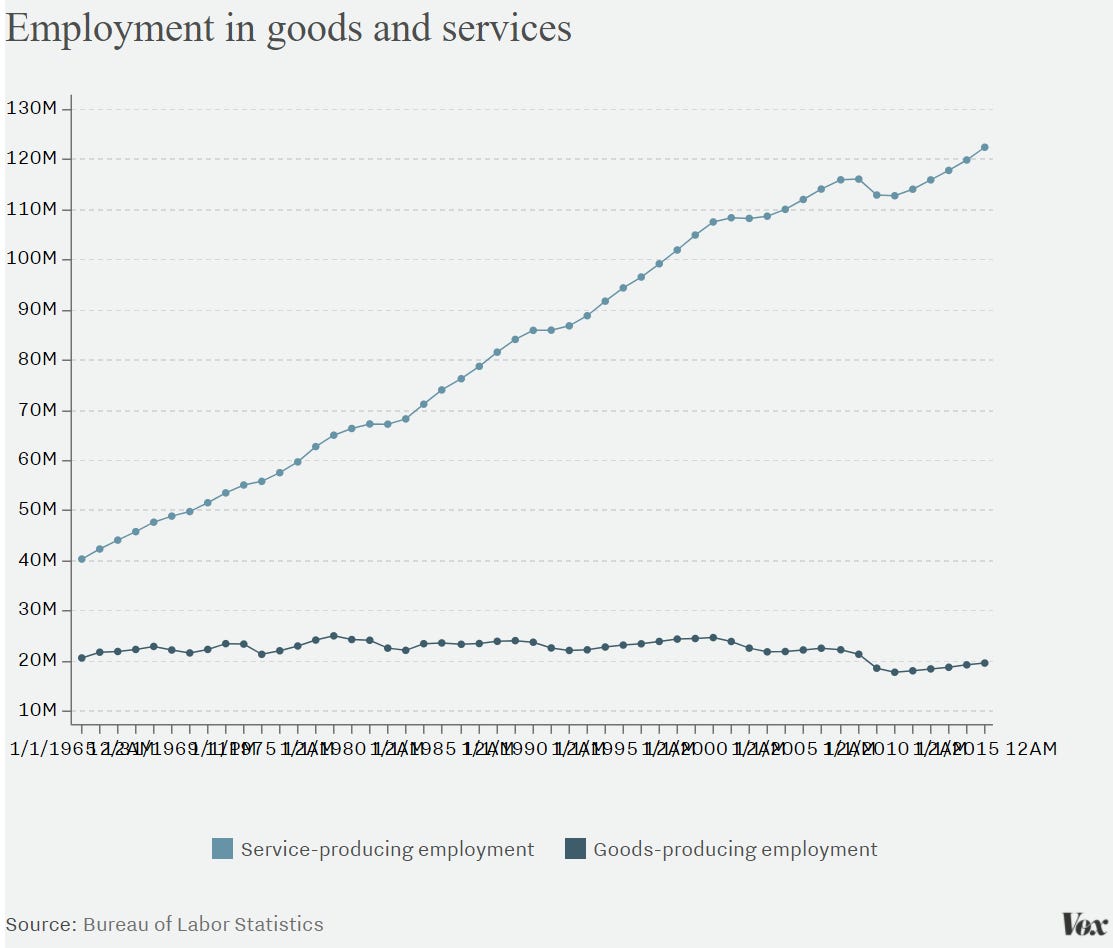

So any increase that has come about in this time has come in technology goods, but all impact on non-technology products and services (including, by the way, banking) has been minimal at best. The fact that the services sector employment growth has dwarfed the goods sector employment growth also provides a bit of support to the argument that it's the goods sector that's getting more productive, while the services sector, despite the benefits of computerisation and so on, still languishes.

A second option is that the organisations were just much less complex back then. When the tasks you need to carry out are simple, then of course you can give more autonomy and flexibility and all the good things. But in today's modern, complex, life is that really the case? No of course not. We're in the midst of this cacophony of complexity, and keeping track of all of it requires specialised skills. And yeah to do that, yes, you need some oversight.

Fair points. I mean, I saw the process of computerisation that the banks went through at one step remove, and they seemed pretty cool. Every quarter end my dad would have his whole team working on reconciling ledgers on paper. His mental maths and ability to add and subtract figures got a great workout, and he used that to beat the teenage me handily in trivial nerdy pursuits. Like most sons I took the defeats with the grace and humility that all thirteen year olds possess.

Computers transformed all of this. Reconciliation became a snap. Regardless of how fast my dad could spot an error or push his team, the computer would be faster. And what's more, it brought forth the ability to let me play solitaire and Prince of Persia in it. Everybody wins.

So what happened? Yes it reduced a huge amount of workload. But new roles came into being, of those tasked with entering the numbers correctly, analysing them correctly, and troubleshooting when the damn thing froze up all over the shop. It's not the case that it wasn't a net positive, it definitely was. It's that the total value added wasn't exactly as huge a number as envisioned in the original proposal. The coordination tax that showed up insidiously took it's toll.

Just like that, the coordination tax took its toll on multiple levels across the bank. Maybe that's why the TFP didn't show such soaring numbers as before.

But is it fair that the job itself has changed dramatically? In some sectors, sure. But in a lot of them things are pretty much the same. Banks do banking, there hasn't been much change there. They even have the same kinds of financial crises. Insurance, similar. Automotive, the cars are getting better and the electric car boom led by Tesla will change the industry, but anyone buying a car today will have roughly the same interests as those doing it a few decades ago. Travel? Same. Telecommunications? Same.

The service delivery might have changed some, and the product too, but the jobs haven't. If you take someone managerial from the 70s and plonk them in today's organisations, after a suitable period of marvel at smartphones, chances are they'll recognise an awful lot. The exceptions are things to do with computers or smartphones. Even there the managerial tasks have an extraordinary degree of crossover.

But there's a third option. Which is that in the old days of autonomy the bosses didn't keep watch and increase the "workplace stress" that McKinsey talks about because they couldn't. Apart from physically traveling or having an occasional chat, they simply didn't have the information or the resources to butt in.

How big a problem is this?

Well for one thing it turns out to be incredibly difficult to tease out. From an input perspective the figures are clear. The employees generally all seem like they're on display, and very few feel the freedom to take autonomous pleasure in their jobs.

It's actually worse than that. The employees usually seem overwhelmed by the complexity increase in point two, at least according to Harvard and McKinsey. And they should know. Since nobody is an expert in everything and since nobody can troubleshoot modern systems easily, everyone becomes experts in one domain. And they specialise. And armoured with the confidence of economists who understand comparable advantage, they push on. Little so they understand that the dependencies they all build amongst each other is exactly what takes away their individual autonomy.

Moreover, the fact that there's increased dependency means there needs to be better coordination between the people, which means there needs to be more and frequent communication amongst all parts, and pretty soon everyone's stuck inside a weird positive feedback loop that nobody quite likes but everyone agrees is important.

Actually it's even worse than that. If employees have specialised skillsets and they perform specific tasks under premade guidelines with minimal autonomy, they become very smart cogs in a highly predictable machine.

This is something I've worked on personally across multiple companies. Any organisational makeover usually relies on trying to put people's job description in a box, linking that box with every other box creating a pyramid starting with the CEO at the top and all the way down. Then not only would you percolate down the targets each needs to hit, but the tendency of "continuous performance management" makes the trend permanent. Bear in mind this isn't the equivalent of factories keeping eyes on their workers forcing them to pee in bottles, jobs we've written off as highly exportable or easily mechanised, but for jobs that we all agree requires high degrees of education and experience to perform in the first place.

The end result is that the modern organisation is achingly similar to it's parents, just much more complex internally, with much less autonomy for jobs to be done and much more stress. It has to be said that part of the stress of course is that today's talent pool is much much wider (globalisation FTW), but it's not just that. It's that if you're a cog in the machine, with specialised tasks and skills, in a funny way you're more easy to benchmark and compare and therefore replace.

III

While it's possible to learn a fair bit from the interplay of several different confounding variables and play with statistical equations, like we did to try and get under the hood of the TFP variation above, one way to look at this might be bottom up. To have a glance at, say 10, professions and changes they have experienced in the past half century:

Bankers: Ever since it started from the benches of Florence, and branched out of the inner sanctums of temples where coins jingled, banks had a rough time getting going. They were outlawed at multiple points, cancelled and resurrected multiple times, overcame several panics and depressions, and came in a form that seems similar today. Banking used to be circumscribed to a few hours a day, with a physical teller. Accounts were tabulated by hand, checked in individual branches, then rechecked centrally. Paper abounded everywhere. Now, banking is not just for bankers. There are multiple systems you need to learn to use, specialisation in multiple parts of banking, reduction of roles like tellers with ATMs, multiple types of IT specialists numbering in the 1000s and with spends in the billions.

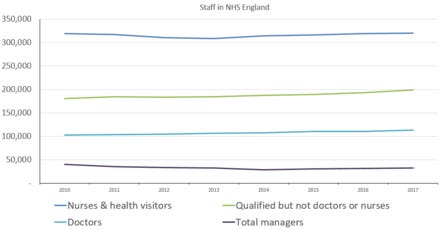

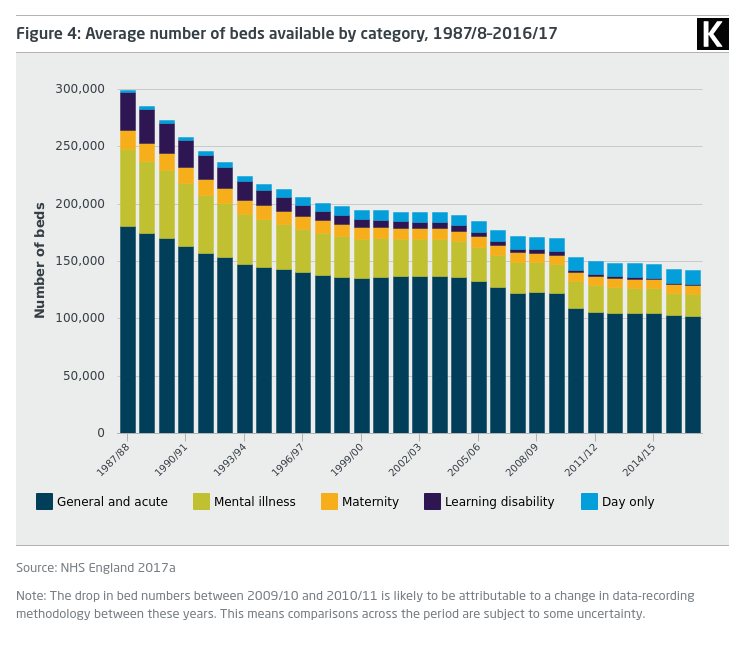

Doctors: In the past time with patients and time to test were both higher for doctors. They had assistants or at least assistance for the administrative parts. Now that has ballooned beyond all recognition. Today the doctors have to use, again, multiple interlocking systems for patient records, billing, health history, research and general record keeping. Even as the number of beds have fallen, administration and technology have helped the spend skyrocket.

Retailers: Here's a job that should be simpler. You buy things in bulk from wholesalers, and sell it for more in smaller packages. Procurement was a challenge, as was sales forecasting. But now? A retailer has a setup roughly analogous to the NASA mission control room, where every variance in the product, supply chain, delivery, sales and returns are measured minute by minute. And guess what, the retailers have to stay on top of all of this, not just the selling part.

Lawyers: A few decades ago lawyers had limited discovery or paper submissions. So they were primarily focused on defining their own strategies and serving the clients. Now there is reams of discovery, shorting out the work for legal secretaries, and a huge amount of work that focuses on opposition research and game planning scenarios. This also creates more adversaries rather than more colleagues, there's rarely an argument in court, and high degree of specialisation amongst lawyers.

Consultants: When McKinsey was a white shoe firm that was modelled after the law firms in the city, highly elite, prestigious and exclusive, the activities they would undertake were mainly one of getting information on the market and competition. It evolved to a world where they would become information brokers through benchmarking. But in todays world since information is everywhere,and analytics have been digitised, consultants today have to become excellent advisors, confidantes to their clients, and able to manage a complex team of data scientists and engineers to develop solutions.

Journalist: Poring over information, fighting to get access to declassified documents, spending ages trying to interview people, spending hours in the library, all were part of a journalist's life half century ago. They were part of an institution that people relied upon and trusted. But now, information is free, as is misinformation, and the job of the journalist is closer to that of the editor, to curate a story from the noise, and to provide an explanatory path. They have to understand and navigate a complex landscape of facts and feelings, and provide their opinions and conclusions to a public in a fashion far more reminiscent of the management consultants of the past.

Musicians/ Actors/ Directors: Make great music, go on tours, the end. That was the job. If you made better music, you sold more. If you made popular music, you sold more. People would discover you through word of mouth, shows and the radio. But now, musicians have to create and maintain an image, curate interactions with the public, manage multiple revenue streams including streaming and record sales, video production and distribution, and more! The artists have become directors rather than performers.

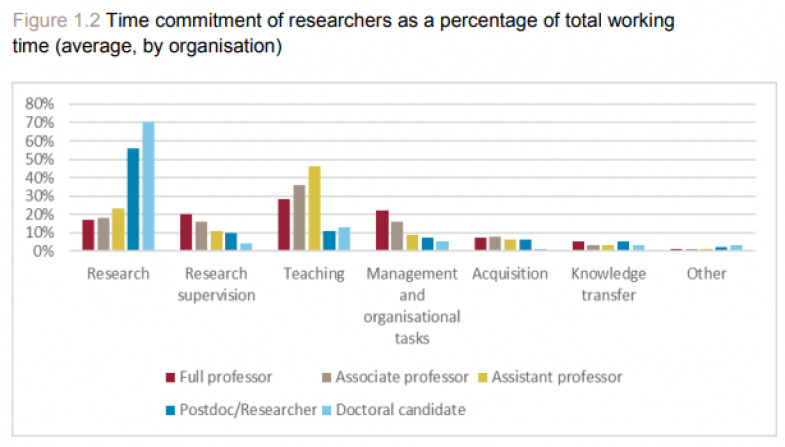

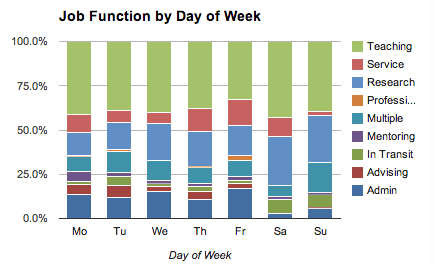

Scientist: If you were a scientist, the focus would have been on research and educating students. There were always managerial and organisational calls upon your time, but they weren't exorbitant. Today the best way to focus on only doing research is to be a Doctoral candidate rather than a full Professor, which seems topsy turvy. For full-time faculty members at four-year colleges and universities, such as Boise State, those figures show that faculty worked 54.4 hours per week, with about 58 percent of time spent on teaching, 22 percent of time on research and 20 percent on administrative and other tasks. Moreover, there are far fewer jobs today with far higher bars to clear and far more competition, making for a uniquely frustrating working atmosphere.

Engineer: Engineering as a profession has gone through a flourishing as technology advanced, and it has split into many different disciplines. Now there are over 16 different engineering disciplines, not counting separate intra-disciplinary cohorts several engineers specialise in, which in a prior age would have been normal.

"Engineers still feel the pressure to improve the performance of their designs, but now they must do it in a fraction of the time they had before." Tom Miller from igus

"Before the 1970s, engineering was highly empirical. The profession has strayed from a lot of that hands-on experience. The tools we now use introduce a level of abstraction ... This has certainly been one of the problems — the math has gotten isolated from the physical side of engineering."quote from James Truchard, who cofounded National Instruments Corp.

"An engineer must be able to collaborate and design virtually with a team distributed all over the world. And that involves communication, which means writing reports, giving presentations, talking to others, and attending meetings. The burden on engineers to communicate effectively continues to grow." Sujeet Chand, CTO at Rockwell Automation

"Today, nothing works without information technology ... And that’s true even though with greater computing power came an equal increase in model complexity." Johannes V from Festo

"Engineers were once praised for expertise in making components. Now we are challenged and expected to be responsible for putting together modules and even entire systems." Tom Stimson from Timken Co

Teachers: Teaching today requires hours more paperwork than what was needed half century ago. Administrative meetings have increased in frequency, amongst the staff and otherwise for prep. There are multiple guidelines on curricula to follow and testing thereafter. There are different pieces of software to use, starting from kindergarten, that handle communication with parents, assessment of the kids performance, and several other observations and analyses. Also the teaching itself has to be highly differentiated per needs of different classes of students. Reporting on the progress has also shifted, with personalised commentary on each student for most assignments. While the tools to do so have indeed become better, the expectations of what needs to be done has skyrocketed!

All of this seems natural to us. Of course it does, why wouldn't it. If you want progress, you have to get with the times. It's not just complexity, it's the cost of doing business in a modern fashion. In many cases it's an improvements. Lawyers don't need to do painful legal discovery drudging through papers. Doctors can know a patient's history at their fingertips. What's lost, however, is a bit more insidious. Charlie Munger has a saying about the issue with scaling something up:

The great defect of scale, of course, which makes the game interesting—so that the big people don’t always win—is that as you get big, you get the bureaucracy. And with the bureaucracy comes the territoriality—which is again grounded in human nature. And the incentives are perverse.

It's somewhat similar in the cases above. In all cases the jobs have become more complex. There is also a major point of similarity to the perverse incentives created by added complexity - just like how increased safety perception increases risk appetite. The more the rules wrap around a profession, the more work adds up at the back. Because you can now automate the report creation often means the creation of a whole lot more reports.! You're not just doing the job you were doing a few decades ago, you are now managing several layers of complexity and making sure you can use the tools. Nobody had to spend time making sure they could use a pencil and paper, but today that's a big percentage of most job descriptions. What this has meant is that you need more qualified managers, i.e., people who have been educated to believe they can manage the complexity, for jobs that didn't use to require them in the past.

A corollary is also that specialists have increased in numbers across the board. Everyone is working within a matrix, and the only way to handle complexity is to slice it into bite sized pieces. So if you're a banker, and suddenly you're living in a much more complex organisation, you will have to reduce the scope of your activities. The internal complexity that you have to deal with reduces the amount of external complexity you can handle. As you are forced to master more things to "do your job", your job naturally narrows in scope.

IV

There's an old tale about five blind men who try and describe an elephant, first described in a Buddhist text Udana in 500 BCE. Stop me if you've heard this one. From one of the sources in Wikipedia.

A group of blind men heard that a strange animal, called an elephant, had been brought to the town, but none of them were aware of its shape and form. Out of curiosity, they said: "We must inspect and know it by touch, of which we are capable". So, they sought it out, and when they found it they groped about it. The first person, whose hand landed on the trunk, said, "This being is like a thick snake". For another one whose hand reached its ear, it seemed like a kind of fan. As for another person, whose hand was upon its leg, said, the elephant is a pillar like a tree-trunk. The blind man who placed his hand upon its side said the elephant, "is a wall". Another who felt its tail, described it as a rope. The last felt its tusk, stating the elephant is that which is hard, smooth and like a spear.

Being a pretty catchy parable it's found its way into multiple texts, across Hinduism, Jain and other Buddhist texts. It crossed the pond in the 19th century to feature in a rather mediocre poem about Indostan by John Godfrey Saxe, imaginatively titled The Blind Men and the Elephant.

One of the reasons it has found purchase in these texts is that it's a rather neat story, easily explainable to everyone. It's highly visual too, you can almost see the blind men groping around in your mind's eye.

The parable, like most good memes, have also changed form several time, though the other versions haven't found much memetic success. There's a version where the men aren't blind, but it's just night. There's a version where it's not an elephant but rather a large statue. There's a version where the men aren't blind and it's a statue and not an elephant, but they're blindfolded. There's a version where ... you get the point.

In almost all of them the point is somewhat similar. How do you know what you know is all that you need to know to come to a conclusion. Or rather, how do you find the limits of your intuition and observation in drawing a conclusion.

It's also the downside of specialisation. You might get great at describing the trunks of elephants, or know all there is to know about the big ears, but without knowing how all the pieces of information link together, you're left extrapolating wildly from small disconnected datasets.

What could this mean? This means that even as we create more specialists than ever before, and as a large number of jobs have become more "mechanised" than ever before. While the rosy outcome might be for us to embrace our "human" side, there isn't enough room for everyone to do that. We can't all be service sector employees to each other, helping maintain the emotional bonds!

Even within a given occupation, day-to-day work activities will change as machines take over some proportion of current tasks. Workers may need different skills as a result. Our model shows activities that require mainly physical and manual skills declining by 18 percent by 2030 across Europe, and those requiring basic cognitive skills declining by 28 percent. In contrast, activities that require technological skills will grow in all industries, creating even more demand for workers with STEM skills (increasing 39 percent), who are already in short supply. At the same time, we foresee 30 percent growth in demand for socioemotional skills.

While there are several avenues for freelancing and creating a new career of ones dreams, they are usually the exceptions rather than the rules. Most of the employment ends up not even being entrepreneurial in the old school and boring sense of the word, such as greengrocers or auto repair shops. It's with the large companies who employ us. Most of us are more likely than not to become employees with circumscribed roles and limited autonomy.

The most frustrating part it, we know this. It's not an inconvenient truth that hides from us, only visible if we seek it out, but rather something that is part of our lived experience. When we try and understand why there is an increasing feeling of alienation within large parts of working population, perhaps part of it is this. Our jobs have transformed in the past half century. We are now responsible for more oversight, do more reporting, and focus on smaller slices of the actual problem, working within faster feedback loops on all of our decisions.

The obfuscation that comes from not being visible at all times is a blessing - it gives us room to work, dream, even innovate. The complexity inherent within our jobs is what makes us feel better about doing them, but complexity of tasks being performed is not the same as the complexity that comes from watching a dashboard like a fighter pilot. We're all looking at a hundred different dials, trying to step in and fix something at a moment's notice, and that's a different level of stress. We run towards specialisation to solve for this issue, but end up making our jobs and lives feeling more like cogs in a machine, and then wonder why we might feel alienated. As Oscar Wilde said, "when the Gods wish to punish us, they answer our prayers."