I.

We’re living through a phase change that is at the root of a lot of our societal problems. It’s the fact that our information networks have become much more dense.

You exist as a node in a network. Other people are other nodes. They send you information, the edges. You process it, you create your own. Information flows in all directions.

There are all sorts of networks. If you imagine all of us as nodes and the information we receive from each other via edges, then the shape of the network defines the type of information that spreads.

When the type of information is extremely tantalising, one that spreads fast, then the whole network gets taken over with that information. And there’s even a tipping point at which the information breaks containment and spreads through the whole network. Here’s an excellent essay on the subject.

It turns out that there's a precise tipping point that separates subcritical networks (those fated for extinction) from supercritical networks (those that are capable of neverending growth). This tipping point is called the critical threshold, and it's a pretty general feature of diffusion processes on regular networks.

When there are a lot of neighbours to which a node is connected, then various types of information spreads much faster through the network. This is called network density, how many edges are connected on average to each node. And increased density means that there’s many more routes by which information can spread.

This is why cities have much higher rates of “cultural transmission” compared to rural areas. Or why in domains like fashion or ideas or innovation or language or even food, the speed of change and variety is much higher in cities. Because each new unit of culture can transmit from person to person so much faster when there are more people it can connect to.

Ok, this is basics about what a network is. But what happens when the entire world gets interconnected such that we’re all connected to each other much more densely? What would have changed in ourselves? Our culture?

Historically, you used to only have a few sources of news or information. Things that percolated through to your network or things you read in the news. Now information comes from all sides, hungry for your attention. And your “processing power” to make sense of this information hasn't meaningfully changed.

Imagine seeing the world from this vantage point. A blinding array of data streaming at you, standing as a node. Some from near, some from afar. You take it all in, process it, and build up a sense of the world from it, including a sense of the other people and their beliefs reflecting back, from near and far.

If you do this, as a sentient being, you can't help but develop a world model. A sense of the world, a sense of what others think of the world, perhaps even another layer or two. Even if you develop it only to help speed up the information processing that you need to do. It will be different in structure for each of you, of course, but part of a shared consensus reality nonetheless. A sense made up of all the information that came your way, including the sense you have of all the sense of information that came other people's way, which helps them process the information flowing their way. Creating a collective sense of what's going on, a knowledge of the shared reality in which we live.

We call this our culture.

Culture is a group's shared collective meaning system, including its values, attitudes, beliefs, customs and thoughts.

Culture is the digital biosphere we create for ourselves. Culture is the infosphere we all swim in. If you think of the information that we all swap with each other as water, culture is the ocean made up of it, or a distilled version of the most common or communally known parts of that ocean.

Edward Hall, in his books Silent Language and Beyond Culture, writes about how culture is composed of the communication patterns, behaviours, and symbols that are shared amongst a group. We can think of culture as the common interconnected web that underlay the beliefs that we all hold, which constantly changes and evolves as our beliefs spread.

This is especially salient because part of the culture now is filled with efforts of many to escape it. This isn’t new, of course, and have existed since Thoreau. But there is an increase in it. People try tools for thought and software to recommend things or remember things, or AI to remember everything they read and interacted with, all so that there can be a way to deal with the information avalanche.

While this makes sense for an individual, the fact that this collectively defines the information ecosystem around us also means that the problem is on the supply side. This is why there is the rise of private spaces, especially since Twitter’s demise. Hence the theory that we live in the dark forest era of the internet:

Is our universe an empty forest or a dark one? If it’s a dark forest, then only Earth is foolish enough to ping the heavens and announce its presence. The rest of the universe already knows the real reason why the forest stays dark. It’s only a matter of time before the Earth learns as well.

This is also what the internet is becoming: a dark forest.

In response to the ads, the tracking, the trolling, the hype, and other predatory behaviors, we’re retreating to our dark forests of the internet, and away from the mainstream.

The push to create private spaces, on discord or group chats, to truly express oneself or let mini-ecosystems flourish, they all are needed to make us stop sitting with our face deep inside the information superhighway. It’s to help make the networks you’re in a bit sparser.

And my thesis is that almost everything that we see that pushes against the cultural state we used to recognise, is as a result of this densification of our information networks. Whether it is group chats, private forums, discord, smartphones that are not that smart, yearning for the flip phones from Motorola, various tools for thought, AI software to help you focus, better note taking tools, the angst against media headlines, the disbelief in economic and political institutions, the underlying sense of malaise that seemingly everyone feels, the vibes…

And the way we’re interconnected changes the way we see and process information that comes our way, which changes the culture. The form of the network changes the way the network operates.

In the era of superfast many-to-many communication, the ideas that spread are the ones which can “take over” the entire spectrum. Small ideas grow, wither, die. It's only the memetic megafauna that survive.

In a sparse network you might have pockets which retain their individuality and survive for longer. Like Galapagos syndrome for ideas. Both good and bad.

Letting your ecosystem interact with the external giant internet might mean it will die out or get outcompeted.

II.

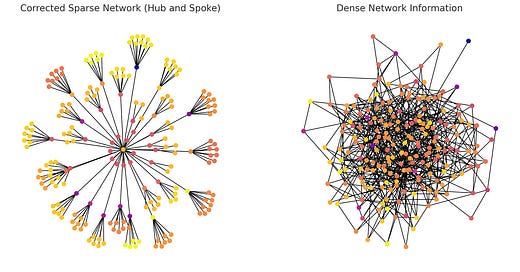

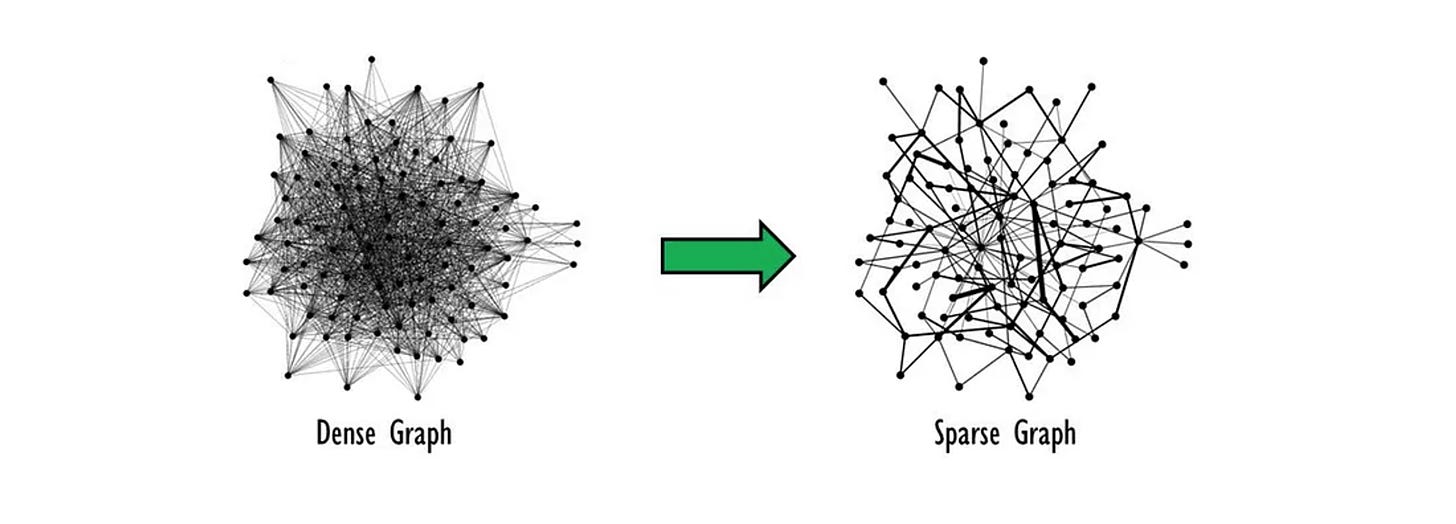

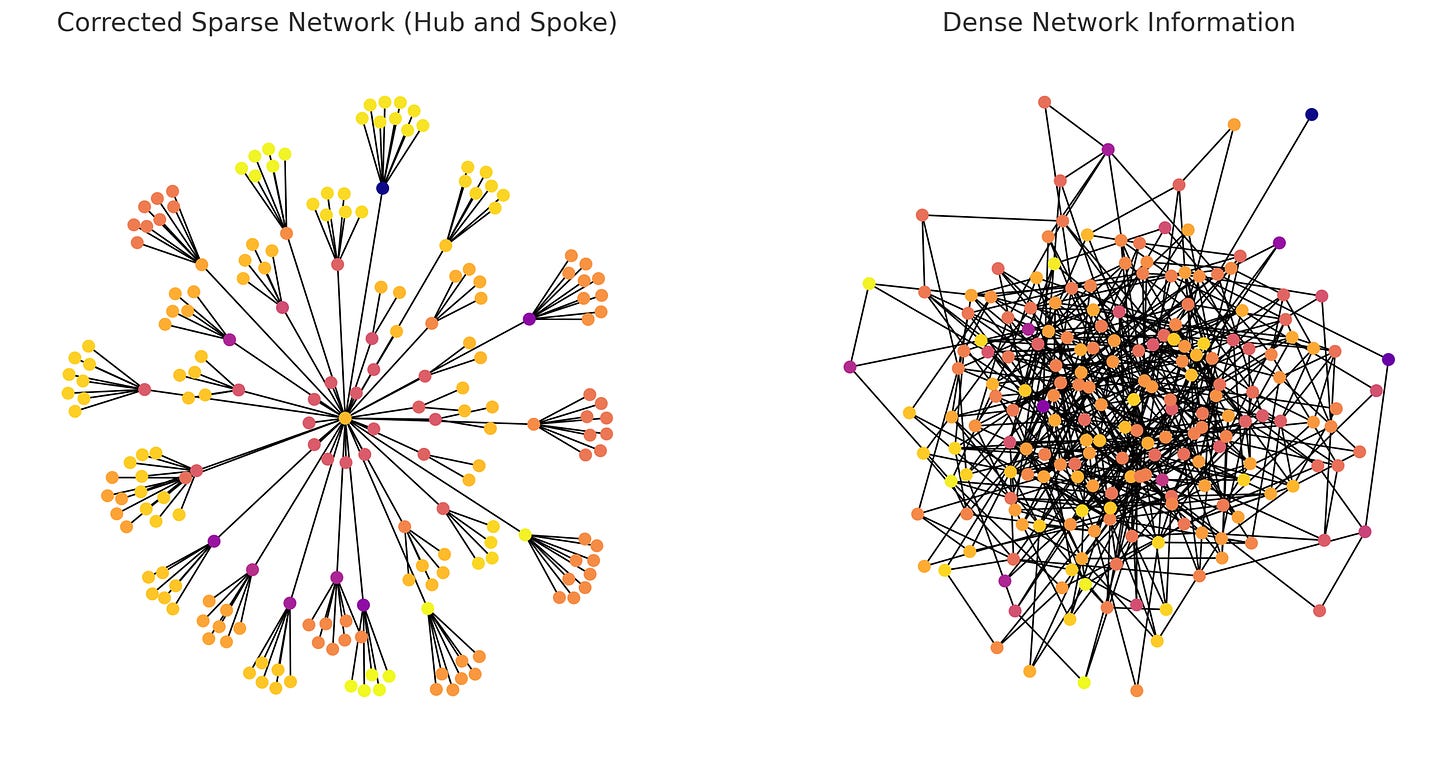

If the way we consume and create and transmit information changes due to the way the network is structured, then the culture itself shifts and changes. You could take a couple of networks with the same number of nodes, and see what they look like if you make one sparse and one dense. Here’s one example.

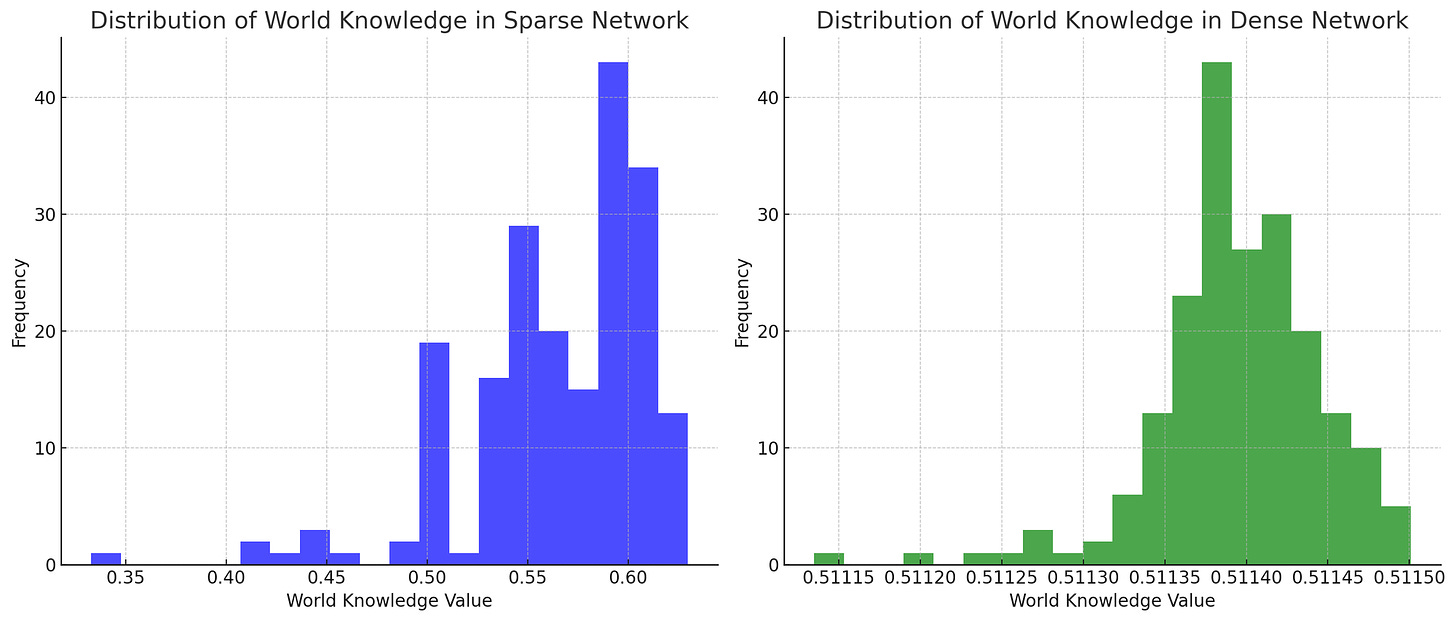

It looks at two networks, with the same number of nodes, and then looks at what things look like once you let information diffuse for a very short while, merely a few cycles. The colours show how much the common knowledge is common amongst the nodes. The sparse network's diverse colour range suggests uneven information distribution, with some nodes as informational "gatekeepers" or isolated pockets. The dense network's more uniform colour shows a high level of information homogeneity, where almost every node quickly reaches a similar level of world knowledge due to efficient information sharing.

The histogram for the sparse network shows a wider spread of "world knowledge" values. This range and the standard deviation indicate a more varied distribution of information among nodes. While in the dense network, the uniformity of colour suggests that almost all nodes have closer "world knowledge" values. Information spreads quickly and uniformly, leading to a more homogeneous knowledge distribution among all nodes.

The lack of sparsity in the networks causes a clear problem for the types of behaviour we care about.

It’s not just true in pocket problems. Here’s a really interesting analysis across open source software, showing the clear importance of both types of networks.

It is argued that [sparse network structures] facilitates the diffusion and generation of ideas among groups, while [dense network structures] affects the implementation of idea within each dense group

The lack of the former means that the information ecosystem we all live in becomes ever more dense and homogenous. We’re stuck surrounded by the exhausts of the stories that pollute the epistemic commons and they together make up the much of the information sphere in which we live.

III.

So the best place to show this, as one would imagine, is social media. And to explore these dynamics, researchers Se Jung Park, Yon Soo Lim, and Han Woo Park examined the Occupy Wall Street movement across two platforms - Twitter and YouTube. The researchers mapped the network by using NodeXL, capturing data from users who tweeted or interacted with the hashtag #OccupyWallSt. And using NodeXL and Webometric Analyst 2.0, the researchers analysed 462 videos, looking at views, ratings, comments, and geographic data.

On Twitter, they found a loosely connected network where a few central users bridged smaller communities, enabling real-time updates and coordination. This isn’t really a surprise, we can see the effects with Elon’s tweets, or the reason why Donald Trump was banned. Twitter’s rapid exchange of information for instance allowed for the organisation of protests and amplified diverse voices, highlighting its unique capacity for mobilising social action. They found what’s called a hub-and-spoke structure.

YouTube, on the other hand, was densely connected. Meaning people were heavily interconnected and didn’t need a “bridge” to jump from subgroup to subgroup. Which meant that it doesn’t really have “superusers” like on Twitter. The users with similar opinions were clusters, voices were reinforced, same keywords were used in tags, solidarity was found. This also shouldn’t be a surprise, it’s why people started worrying about echo chambers or radicalisation, because if you had any propensity for a topic, you would get led down that path through the 2015 version of YouTube.

Park and Lim found YouTube videos related to the Occupy Wall Street movement were highly rated and frequently favourited. This reinforced a sense of solidarity among movement supporters, making YouTube a repository of collective memory and shared identity.

The results show that Twitter users generated a loosely connected hub-and-spoke network, suggesting that information was likely to be organized by several central users in the network and that these users bridged small communities. On YouTube, homogeneously themed videos formed a dense mesh network, reinforcing shared ideas and meanings.

Twitter had a more sparse hub and spoke network, which worked better for information exchange, whereas Youtube’s dense network reinforced shared ideas.

The very structure of the network changed the way information spread, and what information culture emerged as a result.

As with all social studies there are caveats. Some of this might have been due to the way platforms are set up. YouTube is an entertainment platform with a search function, Twitter is an engagement platform for you to create silly memes, but the way the network got structured, maybe because of the way they were set up, changed the information that spread.

Now, 2015 was a long time ago, horrifyingly long for some of us. We’re even more interconnected. 3G gave rise to 4G to now 5G. Videos are ubiquitous, conversation across languages and countries are even more common. For all intents and purposes, the entire world came closer to the old Thomas Friedman line of “no two countries that both had McDonald's had fought a war against each other since each got its McDonald's". It’s wrong, but it’s instructive, the whole world was much less interconnected. (For context, Apple was 7x smaller than today.)

The same thing has happened to our entire modern information ecosystem. We’re all swimming in the same ocean. We used to all have our own tidepools, but they have all merged.

We live in a dense interconnected world, and that changes everything about the information flow within which we live. What’s the impact here?

IV.

So, what does change as the network we’re in gets denser? Summarising a few points from above, and to state it clearer:

Increased virality emerges in terms of the information that seems to win out

Hubs start to have a lower amount of power in the system

There’s much faster synchronicity in terms of information that everyone shares, the “common knowledge”, which also can create echo chambers

The corollary is that there’s also the possibility of much faster innovation of the standing-on-each-others’-shoulders variety, as people learn of each other’s work and build on it

There’s less robustness and stability compared to sparse networks

As a network gets more dense, the nodes in it get connected to each other more and more, the information gets dominated by a factor called M, which is the number of candidate ‘edges’ considered. Increasing the parameter in competitive percolation suppresses the growth of the largest connected component initially, but when it does form, it grows more rapidly.

What this means is that in dense networks you will see information cascading through it more often, once it hits a tipping point of some level of criticality.

This is true across all types of networks. Think about your power grid. Sometimes you might have cascading failures, a problem in our aging power grids. The way to solve it is called “islanding”, the “intentional or unintentional division of an interconnected power grid into individual disconnected regions with their own power generation”. It’s so that if one island collapses it doesn’t take the whole grid with it.

It reduces the economic efficiency of the whole market. So it has costs. But it brings benefits. It’s also more resilient to threats! That’s how they recovered the power grid in Chile after the 2010 earthquake, creating 5 islands which they only connected at the very end.

It is the same with our information ecosystem. We used to have “hubs” which controlled the flow of information. Hence the primacy of journalists and media. And when one got compromised in any way, that substantially changed the way information flows. It also meant multiple ‘islands’ of information. They would get created, grow within their own confines, and only sometimes break out.

When we were all connected into one interconnected dense global infosphere, information spreads much quicker! Virality is more common. The information can come from anywhere and spread, but only those types of information which can spread. You also can’t tamp it down, stories will leak out wherever they can. The extremes are much more extreme, and less predictable.

You’re more susceptible **to echo chambers or filter bubbles, precisely because it’s hard to contextualise or process much of the information that’s surrounding you. Dense networks form tightly knit clusters, but are less likely to form “bridges”.

There’s a much higher volume of information dissemination in the dense climate. And with much much higher turnover. Each day can feel like a year. It can increase polarisation, where differing groups become even more entrenched in their views!

It explains everything from the outrage culture to the success and failure of “wokeism” to the difficulties in the labour market to the idea of the “current thing” which is the thing that becomes a flashpoint. A larger cacophony of voices, where only the most viral memes succeed, and where the only flashpoints are those which can convey the simplest messages to the widest group.

It’s not a problem with the lack of diversity per se, since there’s tremendous information exchange, but that the nodes all get synchronised much more than they would otherwise. The creation is self-consciously knowledgable about what else exists.

This means you get much more standing-on-the-shoulders-of-others innovation, but also much fewer straying beyond the dotted lines.

Ted Gioia wrote about the death of the macroculture and the rise of the microculture.

For example, we might see the end of *CBS Evening News—*which once boasted 30 million nightly viewers, but today it’s closer to 4 million. CBS now consistently places last in news among the major networks.

He’s right, culturally, as the large institutions that existed are being broken down and what remains are the microcultures surviving through blogs and streaming. But while it’s easier for new microcultures to start it’s also true that the sheer number of microcultures makes it harder for new ones to catch on. And that the new microcultures that catch on have a lower diversity than the microcultures that used to exist, since the core is often more fleeting. And it’s even more true that the microcultures have diminished even within the internet substantially since the old days.

V.

The Internet is everywhere, media is linked globally. Social media shrank it further. Every random LinkedIn influencer connection request has 100+ people in common. Twitter is its own memesphere. We’re just much more densely connected.

In an era of unprecedented connectivity and access to information, we expected a renaissance of cultural innovation. Instead, we find ourselves in stasis, where the sheer volume of content has led to a paradoxical cultural gridlock.

The dense network of our modern information ecosystem has plenty of options but inadvertently fostered a homogenization of culture. As ideas spread rapidly across this hyper-connected landscape, they tend to converge rather than diverge, creating what cultural critics call "mimetic isomorphism" – a fancy term for the tendency of institutions (or in this case, cultural products) to become increasingly similar. Same shows with different actors across different versions of the same networks in different languages. This is because we live in a dense network.

This cultural stagnation extends beyond entertainment. Fashion cycles, once dictated by seasonal runway shows, now churn at breakneck speed, resulting in a blur of micro-trends that somehow feel both ephemeral and repetitive.

Which also means the culprit for the cultural malaise isn’t the algorithm as is so often said, it’s the network topology causing different ideas to spread faster. As ideas ricochet across the globe at lightning speed, there's less time for incubation, refinement, and true innovation.

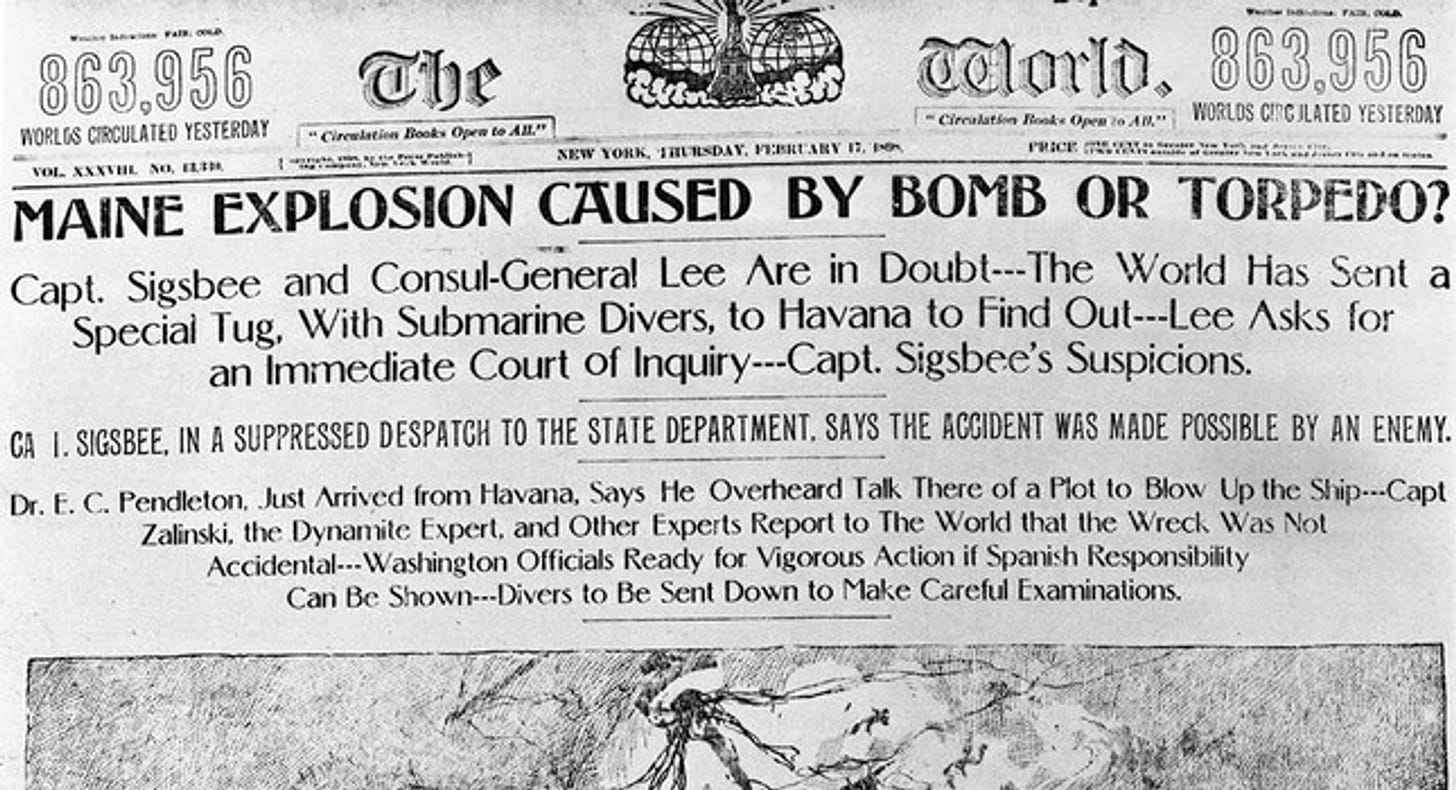

It’s not just the problem with the ideas, as is often said. It’s a problem of the network. We've had virality and fake news since the age of pamphlets.

Or.

One persistent “cottage industry” of fake news in antebellum America was stories of African-Americans spontaneously turning white.

It was so common that it helped build generational fortunes and caused literal wars.

The New York Sun’s “Great Moon Hoax” of 1835 claimed that there was an alien civilization on the moon, and established the Sun as a leading, profitable newspaper. In 1844, anti-Catholic newspapers in Philadelphia falsely claimed that Irishmen were stealing bibles from public schools, leading to violent riots and attacks on Catholic churches. During the Gilded Age, yellow journalism flourished, using fake interviews, false experts and bogus stories to spark sympathy and rage as desired. Joseph Pulitzer’s New York World published exaggerated crime dramas to sell papers. In the 1890s, plutocrats like William Randolph Hearst and his Morning Journal used exaggeration to help spark the Spanish-American War. When Hearst’s correspondent in Havana wired that there would be no war, Hearst—the inspiration for Orson Welles' Citizen Kane—famously responded: “You furnish the pictures, I’ll furnish the war.” Hearst published fake drawings of Cuban officials strip-searching American women—and he got his war.

And yet, this didn’t demolish the credibility of the media or poison the epistemic commons the way we did in the last couple decades, when the very belief in the institutions seems to be crumbling.

It creates some self perpetuating institutions and it creates ebbs and flows in the “current thing” which focuses spotlights, creates chaos, then moves on. This monoculture means you can only “break out” of the information glut by pushing more inflammatory ideas.

What we need are pockets of "cultural islanding" – protected spaces where ideas spread slower. Until then, we find ourselves in a curious moment where, despite having the world at our fingertips, culture seems to be spinning its wheels, stuck in a loop of endless variation without true evolution.

We all feel like we’re living in a maelstrom, confused and outraged not by any one thing, but by a thousand things all fleeting by. And what's common is that feeling of outrage than the outrage over any one thing.

In the old days we used to all consume the same media, tens of millions watching the season finale of MASH, which would never happen today. We thought it meant that we were stuck in our own little islands. Turned out, not really. We watch slightly different streaming shows, and guess what, an entirely new ecosystem sprouted! For a little while.

VI.

When Microsoft researchers Eric Horvitz and Jure Leskovec analysed email and messaging data in 2007-2008, they found an average of 6.6 degrees of separation between 240m people. In 2016, a study by Facebook’s data team found the average degree of separation was 3.57.

The network we’re in has grown denser.

Whether it’s the ubiquity of the same types of media as every streaming network learned the same tricks, the same few lies about the economy, or the media diet filled with stories about California’s high speed rail failures or wildfires, it’s everywhere.

While the internet and constant ubiquitous connectivity we were meant to find our own niches and cliques, 1000 true fans from Kevin Kelly, we instead got entirely subsumed into whatever the current thing is, whatever caught the fancy of the machine.

Algorithms are our interests, refined inside a dense network, reflected back at us. It creates “memetic megafauna”, these feelings or ambient information ecosystem that colours all information that comes our way, which exist much like the pagan deities of our ancestors. They are around us, and affect our perception of the world.

We called it falling prey to the algorithms. As if the algorithm was a “thing” which stood separate to the components that make it up. As if it isn’t made up of us, individually, reacting to the stories that show up in front of us.

It’s not the algorithm, but our interconnected beings acting as a different animal we’ve personified as the algorithm.

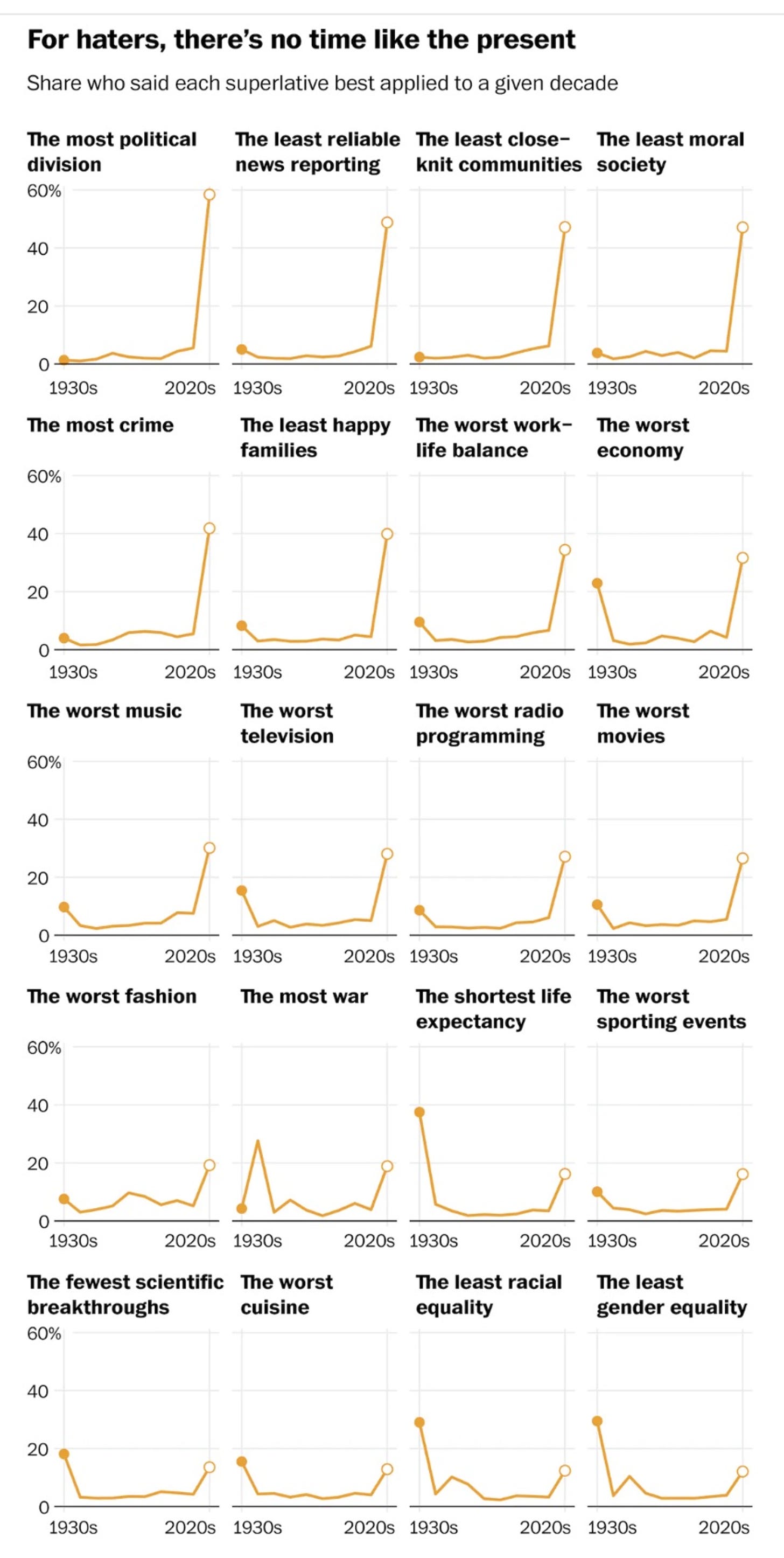

The outcome of having a dense network is insidious but powerful. It means only the narratives which can go viral do go viral. The collective epistemic commons becomes filled with those narratives which outcompete the others and muscle their way to the top. It means that at a time of unprecedented low unemployment, high wages, high standard of living, GDP growth, high stock markets, strong dollar, people in the US still think they’re living in the worst of all possible times. An anti-panglossian sentiment.

It means that everyone is convinced everyone else is having a bad time. We’re surrounded by vibes about everyone’s life getting worse, wars and famine and pestilence and injustice worldwide. We see gaffes and mistakes made by everyone laid bare instantly.

The denser network makes the impact of the message change. It moulds itself to the medium.

At some level of interconnectivity we all fall prey to the weaknesses of information deluge. Our attention is finite and so is our processing capacity for information. You can have the world do a denial of service attack on your cognition by overwhelming it with bits of information, so you’re stuck in place like a fly in amber. And it does this so easily that we haven't even recognised when it happens let alone how to prevent it.

That too is why we have so many tools for thought, and ways to capture notes to search them afterwards, and tools for doing work about work, and endless lists and notes and contextual reminders and and and … It’s why we yearn for cultural islanding. It’s why there’s the neverending “current thing”. We’re all left tilting at the windmill of being a node in a dense network.

I am reminded of Marshall McLuhan.

Hugely insightful, extremely well structured and measured analysis. Thank you Rohit🙏