I wrote a book on AI development, exploring how it works, its history, and its future. Order it here, ideally in triplicate!

That in the long 20th century, for the very first time in human history, the principal axis of history was economic—rather than cultural, ideological, religious, political, military-imperial, or what have you

Summary

Slouching towards utopia is a wonderful, magisterial book by

that shows how humanity is moving towards utopia, even if under duress, bedraggled, one step at a time. It is a grand narrative and travels through the long 20th century, from 1870 to 2010. A quick summary of my impressions, though fair warning since the book defies easy categorisation it’s only a soupçon and not the whole meal.The book puts forth an interesting but ultimately unconvincing grand narrative that globalization, industrial research, and modern corporations were the key drivers of economic progress in the "long 20th century." However, these factors alone don't fully explain the complex and multi-faceted forces behind innovation and growth, which are better seen as stacked S curves that evolve and compete within our demandscape, These are necessary lenses, but perhaps not sufficient.

While markets and capitalism played a crucial role, DeLong somewhat overstates their impact and underplays the role of technology itself as well as social and political factors. The interplay of ideas, knowledge, resources, and talent seems more important. It feels weird to call this utopian book one that doesn’t fully deal with “technology” but it does feel pertinent.

I feel there is a companion biography within the same time period which solely focuses on technology and explains the change in humanity as a way we deal with the powers it deals us. I hope someone’s written it. If not, take this as inspiration and I can be persuaded to write one.

And so, the core question of what enabled the rapid technological progress in the late 19th and 20th centuries remains open. The reviewer suggests factors like the connectivity between inventors, the size of the potential market/reward, and the societal structures shaping individual potential over time may offer more insight.

Overall, the book is intellectually stimulating and highly insightful, and the dichotomy between markets and redistribution is a convenient scaffolding to show DeLong’s incredible erudition. I wish I could read the other half of the book that unfortunately met the editor’s scissor!

This one’s a long essay, as befits a magisterial work. But still readable, as the book deserves. Still, here’s a quick guide. The first three sections are about the book itself and its themes. The next three sections are exploring how we should understand those themes. The final section is my conclusion of how to answer the challenges the book raises. Now, the book.

The Long Twentieth Century

How did the world get to where it is today is a large question. In some ways the ultimate question. And Brad DeLong, economist and blogger extraordinaire, has an answer. That’s his book Slouching Towards Utopia, a play on Yeats’ famous poem, with Utopia substituted for Bethlehem. He wrote a history of the long 20th century, from 1870 to 2010. And necessarily it’s a history that’s extremely entangled with economics, politics and technology.

It was launched to high acclaim six months ago, a 600 page tome with footnotes and indices that make it a great read. New York Times bestseller, FT book of the year, Economist book of the year, the accolades bookcase are full, and rightfully so. It’s … heady, despite apparently originally being double the length. The core claim Brad makes is that this is one long century and its primary driver was economic - not political, not technological, and he sets about to prove this. Which is an incredible task, and makes the book complicated. This is a project that has been in the works for a couple of decades, a magisterial work spanning everything important that happened in the last hundred and fifty years.

To start, there are multiple ways to think about the book. It’s an economic history, it’s a business history, it’s a critical look at the political landscape, and it’s a technological history. It’s definitely the book I’d gift first to someone interested in any of those, because of how much it covers. I got the visceral feeling reading it that I first got reading the History of Western Philosophy from Bertrand Russell.

The sheer size and scope of the book also occasionally undermines its own narrative, so what you’re left with often are just perfect morsels of historical delight, but not quite a meal. Time and time again, as soon as you get interested, you move forward. The inevitable chronological current carries you through the greatest and most important events of the 20th century with a speed that is dizzying, in service of unpacking the claim that the hundred and forty years from 1870 to 2010 comprise the long century. And that they were the subject of two opposing forces - the Hayekian ideal of free markets, and the Polanyian ideals of redistributive justice and pluralist human conception.

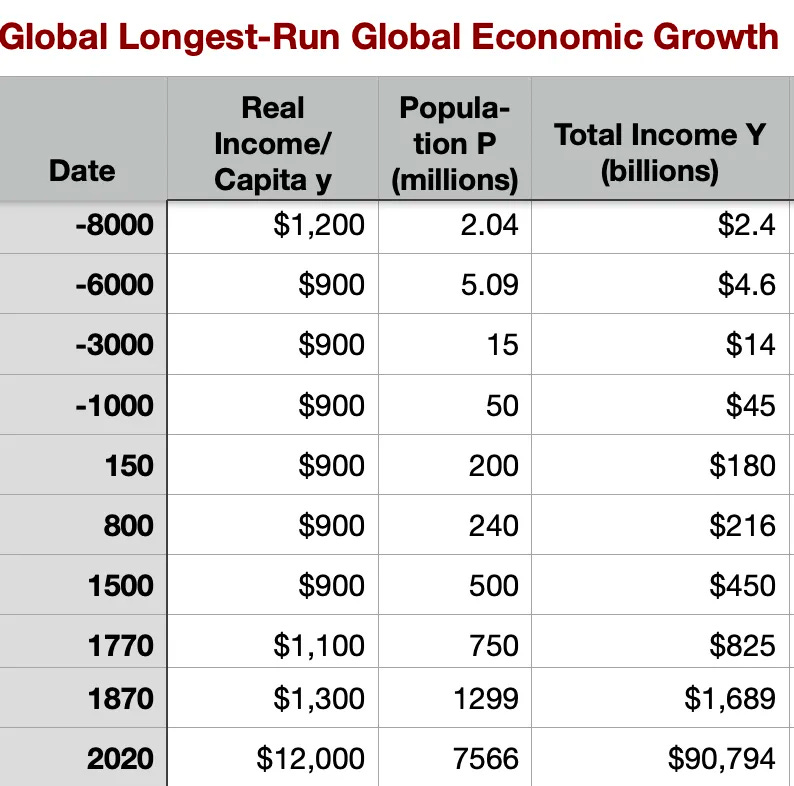

But first, why 1870? Well, because

According to the best estimate, between the birth of Jesus and the beginning of the eighteenth century, the living standard of an average person rose by barely one third—1.5 percent every 100 years. Even after 1750, when the economy began appreciably expanding thanks to the steam engine, improvements in the welfare of a typical person remained paltry, scarcely doubling over 120 years in the global North as the benefits of economic expansion were matched by population growth.

The trivial reading of this is that it’s the time when most things happened, so by definition it’s most consequential. This is true, but boring, so let’s skip past this.

The better reading is that it’s reflecting what was an inflection point for humanity. As DeLong says:

What I call the “long twentieth century” started with the watershed-boundary crossing events of around 1870—the triple emergence of globalization, the industrial research lab, and the modern corporation—which ushered in changes that began to pull the world out of the dire poverty that had been humanity’s lot for the previous ten thousand years. What I call the “long twentieth century” ended in 2010, with the world’s leading economic edge, the countries of the North Atlantic, still reeling from the Great Recession that had begun in 2008, and thereafter unable to resume economic growth at anything near the average pace that had been the rule since 1870. The years following 2010 were to bring large system-destabilizing waves of political and cultural anger from masses of citizens, all upset in different ways and for different reasons at the failure of the system of the twentieth century to work for them as they thought that it should.

And also:

After 1870, humanity's deployed technological capabilities and thus potential prosperity doubled every thirty-five years—and with it came economic creative destruction that reduced old economic structures to rubble and built new ones, and did it again, and again, and again, every single generation. Before 1870? From 1770-1870 humanity's globally-deployed technological prowess had a doubling time of about 150 years—not 35. From 1500-1770 it had a doubling time of 500 years. And before 1500, we are looking at a doubling time of 2000 years.

There are three parts to his argument, which is that 1) Globalization, 2) the Industrial Research Lab, and 3) the Modern Corporation, came together to create untold prosperity, which was taking us towards utopia. Except that it got waylaid by our infatuation with the markets (the Hayekian angel on one shoulder overpowering the Polanyian one on the other), and it led us astray.

Hence the slouching. The anecdotes are wonderful. The stories are remarkable. The erudition induces the green eyed monster to raise its head. But the narrative is flimsy. We live amidst the growth pangs of a golden age which we, in part, indulge in and squander away.

If you were the type of person who immediately leapt to find answers, it could be in two parts:

There was no magic in 1870. It’s a narrative convenience, sure, but there is no step change, it’s just the continuation of many long trends coming to fruition.

There are many ways to slice and create a starting point. You could do the industrial revolution, the scientific revolution, the Enlightenment, the reduction in population growth rate - each are ways of seeing the elephant, but none are comprehensive

DeLong suggests that the central problem, the reason for slouching, is this:

One reason why human progress toward utopia has been but a slouch is that so much of it has been and still is mediated by the market economy: that Mammon of Unrighteousness. The market economy enables the astonishing coordination and cooperation of by now nearly eight billion humans in a highly productive division of labor. The market economy also recognizes no rights of humans other than the rights that come with the property their governments say they possess. And those property rights are worth something only if they help produce things that the rich want to buy. That cannot be just.

We escaped the Malthusian trap as our productivity started outpacing the population growth, that our innovation started getting industrialised and indeed commercialised, and that the vast sweeps of political economy existed to get both these points, seemingly in tension, into a working relationship.

This still leaves plenty of questions. Sure, globalisation is useful, but it existed before too! We had industrial revolutions before, joint stock companies before, and we had various groups jointly researching interesting phenomena before. Why were they not part of this particular long century? So let’s look at them.

I. Globalisation

Globalization isn’t just a fancy modern thing, something that only came into existence due to our shiny new technologies, transportation methods, and communication systems. Globalization in some ways has been around since ancient times when trade networks were the highways that connected far-off lands and cultures. To start, this is what DeLong states regarding his globalisation narrative.

There was the globalization of transport, too, in the form of the iron-hulled, screw-propellered oceangoing steamship, linked to the railroad network. There was the globalization of communication, in the form of the global submarine telegraph network, linked to landlines. By 1870 you could communicate at near–light-speed from London to Bombay and back, by 1876 from London to New Zealand and back.

Transportation and communication technologies did advance in the late 1800s such that distances shrank. But this wasn’t exactly new, but the continuation of a trend happening since we first started setting out on ships and boats together. There existed long-distance trade routes that brought together entire diverse regions and civilizations. The Silk Road, for instance, was this complex web of land and sea routes that connected China, India, Persia, Arabia, Europe, and Africa from around 200 BCE to 1400 CE. The eponymous silk, spices, porcelain, metals, textiles, ivory, gems – were all traded, along with ideas, religions, languages, and technologies.

And let's not forget the Indian Ocean trade network that linked Southeast Asia, India, Arabia, and East Africa from around 800 CE to 1500 CE, making it possible for commodities like cotton, pepper, cloves, cinnamon, gold, and later slaves to be exchanged. These trade networks weren't just about the money; they were also about creating economic interdependence, cultural diversity, and even political alliances.

Now, you could argue that they weren't quite on the same level as modern trade flows, involving just a small portion of the world's population and output at the time. Plus, there were all sorts of barriers and risks to contend with, like tariffs, piracy, wars, diseases, natural disasters. But, let's not discount their relative impact on the societies involved either. After all, exposure to new products, ideas, beliefs, and practices could have far-reaching effects on people's preferences, values, institutions, and identities.

Even today we discuss languages that evolved and people who changed from these routes. And there were feedback loops and spillovers that amplified these effects, trade stimulating innovation, specialisation, competition, cooperation, diffusion of technologies.

DeLong’s thesis is that it’s not sufficient for trade to happen, but the development of a globalised market economy to emerge.

Unmanaged, a market economy will strive to its utmost to satisfy the desires of those who hold the valuable property rights. But valuable property owners seek a high standard of living for themselves… Moreover, … the market economy sees the profits from establishing plantations.

The difference is that prior to 1870 or thereabouts, the claim that “markets will lead to prosperity” would’ve still been true, but perhaps banal, definitely not transformative the way we see it today. Because when we say “markets”, we don’t just mean the trade of goods and services, but the invisible web that forces someone far away to create an innovation impacting a particular type of plastic that forever changes the way we deliver vaccines to our children! It’s the constant striving to link innovation with a common mercantile purpose that also satisfies oneself.

The previous markets too led to the emergence of whole empires and colonialism that spanned multiple continents and regions. Not even the latest colonial ones. Take the Mongol Empire, for example – the largest contiguous land empire in history, covering most of Asia and parts of Europe and Africa from 1206 CE to 1368 CE. The Mongols managed to unify a pretty diverse bunch of folks under their rule, promoting religious tolerance, cultural exchange, and even setting up a common legal system and postal service. And they were all about trade and commerce across their vast territory. Then there's the Spanish Empire, one of the first global empires in history, which reached its peak in the 16th and 17th centuries. The Spanish colonised large parts of the Americas, Africa, and Asia, exploiting natural resources and labour forces, spreading Christianity and Spanish culture, and introducing new crops, animals, and diseases.

These empires didn't just have political and economic ramifications; they also had deep social and environmental impacts. So, what do these empires tell us about globalisation? You could argue that they were more about coercion than consent, extraction than exchange, homogenisation than diversity – I mean, we're talking about violence, oppression, exploitation, conversion, assimilation, and the like. But on the flip side, they could also be seen as sources of integration rather than fragmentation, cooperation rather than conflict, and hybridisation rather than purity, as they involved negotiation, adaptation, resistance, syncretism and creolisation.

The rise of Globalisation here is a stand in for more than just markets. The commercial apparatus we made is good, perhaps even necessary, but its the drive that somehow taught us that individual effort in making new things can satisfy others, who will then shower you with praise and wealth, that kickstarted the positive feedback loop.

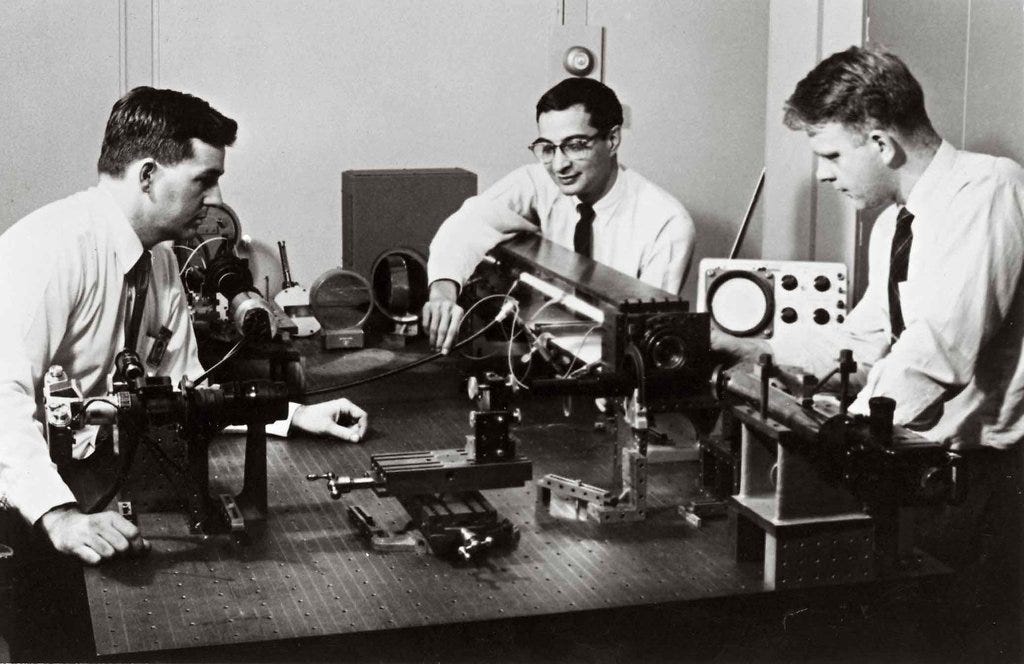

II. Industrial Research Lab

The second ingredient is the Industrial Research Lab – that modern bastion of innovation where great minds gather to push the boundaries of technology and knowledge. It is how we created some of the greatest innovations of the 20th century, from Bell Labs to the semiconductor world.

Four percent of Americans had flush toilets at home in 1870; 20 percent had them in 1920, 71 percent in 1950, and 96 percent in 1970. No American had a landline telephone in 1880; 28 percent had one in 1914, 62 percent in 1950, and 87 percent in 1970. Eighteen percent of Americans had electric power in 1913; 94 percent had it by 1950.

But before we had these shiny temples of science, there were precursors and antecedents that can be traced back to before 1870 too. And if we’re to be critical of the specific organisational structure too, scenius formation happens time and time again across the globe, from Baghdad to Paris.

Let's rewind the clock first though and take a look at the early European workshops and laboratories that served as hives of knowledge and innovation. Among these were the Renaissance "studios" where master artists and their apprentices would collaborate and experiment with new techniques and materials. These studios not only produced breathtaking works of art but also enabled the cross-pollination of ideas between different disciplines, such as painting, sculpture, architecture, and engineering. Just think about Leonardo da Vinci's workshop – a veritable playground of creativity where art and science intertwined.

There were "cabinets of curiosity" that popped up in the 16th and 17th centuries. These collections, often owned by wealthy individuals, were like proto-museums and featured all sorts of exotic and unusual items – natural specimens, archaeological artefacts, scientific instruments, and more. The inquisitive minds of the time would gather around these collections to study and discuss the objects. These cabinets of curiosity were, in a way, the intellectual salons of their time.

This changed as we moved into the world of the "scientific societies" that began to emerge in the 17th and 18th centuries. The Royal Society of London, for example, was founded in 1660, dedicated to the pursuit of scientific knowledge. To bring together like-minded thinkers who shared their discoveries, conducted experiments, and published their findings. The Royal Society not only provided a platform for collaboration but also helped establish standardised methods and practices that laid the groundwork for modern scientific research.

Is the difference that these are primarily arenas for learned scholars to debate ideas, but not necessarily to create technology? High craftsmanship was necessary to make telescopes or machine tools for instance, so this would seem unfair, like we’re drawing a line in the sand.

As we enter the 19th century, we find the birth of the modern research university. Germany was at the forefront of this movement, with institutions like the University of Berlin (founded in 1810) and the University of Göttingen (founded in 1737, but with a major reform in 1807) that focused on the integration of teaching and research. These universities housed research laboratories where professors and students would work together on groundbreaking scientific projects. The German model was soon adopted by other countries, and by the late 19th century, the research university had become a key player in the advancement of science and technology. Surely this matters!

So, what do these historical nuggets of wisdom tell us about the evolution of the Industrial Research Lab? Well, for one, they show us that the spirit of collaboration, experimentation, and cross-disciplinary thinking has been alive and well for centuries, and tried in multiple forms.

Furthermore, they reveal that the development of the modern research lab was a gradual and organic process, shaped by a diverse array of institutions and practices that evolved over time. And finally, they remind us that the pursuit of knowledge and innovation is a timeless human endeavour – one that has been nurtured and celebrated in various forms and settings throughout history.

The famous Bessemer steel didn’t emerge from an industrial research lab, and was rather quickly followed by others who improved the method further. This is a discovery disseminating through the network, and getting improved at every turn, because in improving it there exists the tantalising prospect of fame and riches. The same that has tempted all men throughout history. As DeLong himself writes

For thousands of years steel was made by skilled craftsmen heating and hammering wrought iron in the presence of charcoal and then quenching it in water or oil. In the centuries before the nineteenth, making high-quality steel was a process limited to the most skilled blacksmiths of Edo or Damascus or Milan or Birmingham. It seemed, to outsiders—and often to insiders—like magic. In the Germanic legends as modernized in Wagner’s Ring cycle operas, the doomed hero Siegfried acquires a sword made by a skilled smith. Its maker, the dwarf Mime, is in no respect a materials-science engineer. His brother, Alberich, is a full magician.7 That changed in 1855–1856, when Henry Bessemer and Robert Mushet developed the Bessemer-Mushet process.

The industrial research lab is a success but borne of the fact that bringing people together to attack thorny problems has always been successful. It’s the scenius that’s important. What we have today is the successor to a reasonably well understood format that’s changed and evolved through time.

In fact now, in the 2020s, we see the ossification of old industrial research labs and are desperate to find new outlets. We scoff at the large extant R&D departments even within the historically profitable Googles of the world, even as the development comes from upstarts who no longer need depend on the largesse of the mothership to get funding to try their crazy experiments. But if we want the Transformers paper or Tensorflow or Pytorch, it’s still the individual company labs that oblige.

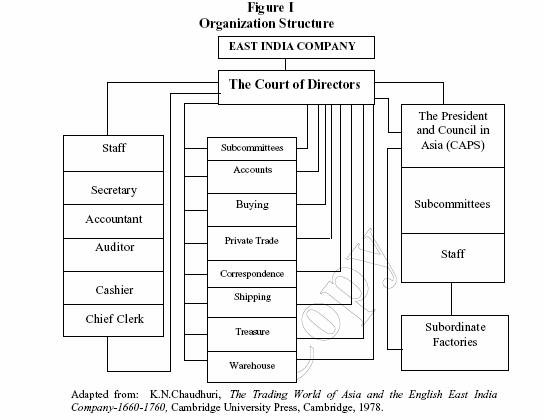

III. Modern Corporation

The Modern Corporation, that seemingly immortal beast that dominates the global economic landscape. The corporate megafauna that we look at as a marker for clear success. Even here, lest you think it's a product of recent times, I invite you to take a stroll down history's winding path to explore the antecedents and precursors of this omnipresent entity.

This is also the weakest part of the triad. While I understand why communication and transportation can be said to have kicked off globalisation, and why the industrial nature of technological research changed the format from scholarly pursuit of scientific research in salons in the industrial research lab, corporations are a legal fiction we’ve seen evolve to generate capital and create wealth through centuries.

The corporation is used in the book mainly as a way to disseminate the great technologies that the industrial research labs created. A sort of diffusion engine. But this isn’t the case when you look historically!

Before the age of the Modern Corporation, there existed a plethora of organisational structures that contributed to the evolution of this complex creature. For instance, the ancient Roman institutions that laid the groundwork. In the Roman Empire, we find the "societas," a partnership structure that allowed individuals to pool their resources and engage in commercial endeavours, as well as the "collegia," guild-like associations of artisans and merchants. These early arrangements had their share of fragility, but they demonstrated the power of collective action through organisational forms.

Moving forward to the mediaeval period, we encounter the "guilds" – associations of craftsmen and merchants that played a significant role in shaping the economy of European cities. Guilds fostered cooperation and mutual support among their members, regulated quality and pricing, and provided social services. While these organisations had their limitations and often fell victim to rent-seeking and protectionism, they were a testament to the importance of trust and reciprocity in a world of uncertainty and opacity.

Or let's fast-forward to the dawn of the joint-stock company – the ancestor of the modern corporation. The Dutch East India Company, founded in 1602, was among the first of its kind, allowing investors to pool capital and share risks while pursuing trade and exploration in the far reaches of the globe. The joint-stock company was an ingenious innovation that harnessed the power of risk-sharing and limited liability, enabling enterprises to undertake ambitious and capital-intensive ventures.

In the 18th and 19th centuries, we witness the emergence of the industrial revolution and its profound impact on the organisation of businesses. Factories and mills, driven by new technologies and powered by steam, brought forth the need for large-scale coordination and capital investment.

As a result, the corporation began to assume its modern form, with hierarchical management structures, centralised decision-making, and a focus on efficiency and growth.

These early iterations of the modern corporation were prone to the same pitfalls that we encounter in our complex, interconnected world: concentration of power, short-sightedness, and susceptibility to shocks and disruptions. But these entities evolved and adapted over time, drawing on the lessons of history and the ingenuity of the human spirit.

The story of the modern corporation is a tale of trial and error, of innovation and adaptation, all unfolding against the backdrop of a complex and uncertain world. The precursors of the modern corporation serve as a reminder of the rich history that has shaped the economic landscape we inhabit today. And as we strive to navigate the unpredictable and ever-changing future, we would do well to draw on the wisdom of the past, embracing the principles of risk-sharing, cooperation, and adaptation that have enabled the corporation to endure and evolve.

What this tells us is also that the modern corporation is the latest way in which we’ve decided to structure ourselves so we can do the really hard things like convert sand into H100 chips and create a magic rectangle that lets us read each other's innermost thoughts.

The older organisations did incredibly hard things too. The East India Company conquered a continent, and created an empire. They did this though disadvantaged by populace, time, often money and the lack of any meaningful coordination or communication ability. They didn't have Slack!

So when we think about the rise of the modern organisation, whether that’s Henry Ford’s assembly line or IBM’s mainframe business creating software, their shape is more an indication of the complexity of what they’re working on, more than a particular innovation.

In other words, this wasn’t a choice, but an emergent phenomenon. Like a Lego house that you overbuilt enough that it became a tower.

Wherein the Grand Narrative starts to look a convenient fiction

From previous sections we see that if we consider the triad that holds up the Grand Narrative, they’re all indicative of a strong Hegelian power. But that’s okay, grand narratives are built on shaky grounds, and that’s why Wittgenstein called it nonsense. It’s as if we’re figuring out what an elephant is by touch alone.

But us today, we live in the times after the supposed boom, when once great organizations suffer from a surfeit of goodness and have been foie-graed to stupor. Is this due to a lack of globalisation, a reduction in the industrial research lab, or indeed a lack of the modern corporation? No. The FDA stands right at the top of the global order. It’s preeminent and highly prestigious. What about its users? The pharma companies too have the largest and probably most successful research labs in the world, not to mention the technology companies. In fact to their detriment because they can’t seem to stop hoarding talent and producing papers. And these modern corporations, they are unsurpassed in both their profitable success and their impact on the world.

But the success they wrought by being the force that industrialised a particular form of inquiry and knowledge is somehow not enough to get them to either speed up the drug discovery process or the regulatory oversight process.

Which means that the long century died not because we weren’t able to do the Polanyian redistributive justice, but because success brings new challenges, and one of those challenges is the ability to deal with scale!

That is my contention. Once we reached a point where an individual could sate the demands of a large number of people, should they create something new, and it became possible to create new things, a dam broke!

The progress we have had is because we bridled our most mercenary selves and put it to work trying to make the collective world a better place. “Hey, you want to get rich and famous,” it says to us, “why don’t you try and do something?” Often this means doing Tiktok videos, but occasionally it also means discovering mRNA vaccines.

The fact that this drive can have a negative consequence isn’t indicative of the fact that the drive in itself is evil. It’s that when you harness the mercenary instinct and push full throttle, at some point the machine eats itself. We can stave it off by setting up a welfare state or taking care of those disenfranchised a bit more, but it’s still the same beast.

In fact, DeLong mentions this several times. This, and a heavy dose of luck! The absolute miracle of the Permian age which gave us cheap coal which got brought closer to the surface as the glaciers retreated, giving an abundant energy source for the late 1700s industrial miracle.

At which point you have to wonder. If we had the following, is it really a surprise that they combined specifically at some point?

the beginnings of an enlightenment and knowledge revolution, bringing together ideas from far and beyond!

the beginnings of an industrial revolution, complete with machining and energy usage, not to mention steam!

the energy source in abundance from which you could construct machines!

Especially in the creation of an economic miracle? The knowledge allowed us to harness the energy which allowed us to build machines which allowed us to serve the same needs of others we knew all along - food, shelter, clothing, war, communication - and spread like water on the sidewalk filling every nook and crevice it could find!

DeLong argues by 1870 the world had already seen multiple large mercantile and military forces that took over and traded with large swathes of the world.

But as we’ve seen, 1870 feels much like the continuation of a trend long since underway, just reaching fruition. It’s like seeing rice get cooked or water boil, there’s some form of a phase transition, but the process isn’t new. The fact that an exponential curve has a hockey stick moment says more about our pareidolia than about reality.

The book feels in some ways like the antecedent to The Great Stagnation by Tyler Cowen. It lays out what we had, so that we may lament what we lost, and what might yet come. But in focusing on the specifics of what gave us the age of plenty - globalisation, the lab and corporations - it also misses the fact that we have all three in abundance today, much more so than we ever had in the 1870s or 1900s. But it turns out to be not enough, because it’s only part of the story.

For the other vignette, what about the Global South? Much of it was under colonial siege during this long century, and the colonisation in many ways was entirely subservient to the political ideologies at home.

Europe—or, rather, Spain and Portugal—started building empires in the 1500s. It was not that they had unique technological or organisational powers compared to the rest of the world. Rather, they had interlocking systems—religious, political, administrative, and commercial—that together reinforced the reasons to seek power in the form of imperial conquest. Empire building made political-military, ideological-religious, and economic sense. Spain’s conquistadores set out to serve the king, to spread the word of God, and to get rich.

This was similar with the Portuguese, later the Dutch, French and even the English. DeLong’s account shows that by the 1870s empires were no longer so prosperous, because the logic of cheap labour and captive markets weren’t needed for economic prosperity.

But India remained under imperial rule until the mid 1900s, the crown in the British Empire. Egypt declared bankruptcy in 1876 and later the British troops came in and occupied it. China suffered the Taiping Rebellion, and were economic weaklings with limited ability to even enforce the levies they were charged with for much of the early 1900s. In fact the success story in Chinese mining in the early 1900s was Herbert Hoover, who despite being besieged under the Boxer rebellion, got the Kaiping mine as a British flag enterprise under his personal control, and did remarkably well.

None of this is the market’s invisible hand, nor is it the modern industrial methodology that spread the globe. This is the old fashioned way of smart industrialists taking advantage of some form of chaos and working things out for themselves. At worst we see the Adam Neumanns of the world doing the same, and at the best we have a working mine!

There is no simple, straightforward, compelling narrative that can place the entirety of the 20th century in perspective. History is notoriously multi-threaded, and the century when all of us got connected with each other and our inventiveness exploded is perhaps the worst century to try and do this in!

Wherein the markets are absolved of some of their sins

A bigger problem, however, is the role that the antagonist in the book plays. The Mammon who makes us slouch, which is our overwrought love for the markets.

Hayekian markets vs Polanyian equitable distribution is a convenient way to structure the narrative, a history of the most turbulent part of human history thus far, but it doesn’t hold up. It’s rather simple to say there are two sides - one that thinks about how we can grow the pie and another that thinks of how to apportion the pie - but once you’re done marvelling at that rhetorical move, it doesn’t quite make sense. This is the melancholic heart of the book:

But Karl Polanyi responded that such an attitude was inhuman and impossible: People firmly believed, above all else, that they had other rights more important than and prior to the property rights that energised the market economy. They had rights to a community that gave them support, to an income that gave them the resources they deserved, to economic stability that gave them consistent work. And when the market economy tried to dissolve all rights other than property rights? Watch out!

This is the reason DeLong thinks we’re only slouching towards utopia. Our love for the market forces have created natural obstacles in front of us, which in our blind embrace of them have led us astray.

But is it really the markets that have caused the slowdown of our progress towards utopia? They’ve had problems, we’re reeling from one as we speak, not to mention the regular financial and economic crises we’ve seen every decade or so, but that’s not a slowdown per se. In the last three decades, at the height of our market based decadence, we’ve seen the best of technological innovation flourish - from mRNA vaccines to the transformer restarting the AI summer. Enough so that there are legitimate worries about how this will end the world!

It’s not just the markets, but rather it’s the apparatus we’ve built around the markets, to manage the markets, which got ossified. In the deluge of information we’ve basically made each of our governing bodies into oracles. Congress doesn’t really pass laws anymore, FDA approvals are slow, drugs tested don’t pass enough, and we put unreasonable demands on someone to build a house, much less a nuclear reactor.

None of which are the market’s fault! All of which are the fault of our response to the market failures - both real and imagined. As Ramez Naam said in his talk, whether it’s on clean energy or elsewhere, it’s no longer economics that’s the obstacle, nor technology, it’s NIMBY-ism and permitting.

In the financial markets, we see how we need efforts from thousands keep it functioning - we need the prices to be accurate, we can’t have insider trading, we need the public to have reputational belief, we need custody services, we need regulations to protect the gullible and regulations to curb the overenthusiastic. It’s the job of many lifetimes to get a functioning market.

There is no blind love for it in many places outside of an academic setting or a polemical discussion. What there is, is a sort of measured respect.

Another way to think about this is are democratic movements and regulations aimed at apportioning the pie part of Polanyian distribution question, or a time-adjusted Hayekian market question (to change the apportioning is to enable larger market movements in the future)?

That last is a puzzle: communications and transportation around the entire globe was SO much easier in 2010 than it has been in 1870. So why then was the world a more unequal place, looking across countries, in 2010 than it had been in 1870? Nay, not just a more unequal place, but a grossly and extraordinarily more unequal place.

Is this true? The inequality inherent in the world can be seen in two ways - one is to note that if any part at all of humanity, even a lost tribe in the Amazon, keeps to the living standards or lifestyle of the mediaeval ages, the inequality would doubtless increase because the “best we can be” is now indexed to Elon Musk and Bill Gates.

Another way to see it is by looking at the medians or averages of the life we now live, which is one where China (China!) decreased the population living in dire poverty by 600 million in the last few decades. That isn’t just societal largesse or redistributive justice, it’s the benefit of a globally resurgent technology-led economic force which can bring the best of humanity even to those the worst-off.

The key missing question is why these three factors, or rather their particular forms, came up in the first place. All three, as we saw, were underway for a while.

The best argument to this is a book by Howard Bloom called The Genius of the Beast. Howard was a music publicist in the 70s and 80s for some of the most popular singers and bands, including Billy Joel, Michael Jackson, AC/DC and Prince. He has one of the most incongruous sets of books ever published by one man - a book on Islam, an autobiography, and three books on human evolution, of which this is the first.

And his thesis in The Genius of the Beast is simple: there exists a superior force that forces people to create things that other people want, which is capitalism. Shorn of all the anecdotes and all the illustrative stories, the thesis is that the process of exploration and then exploitation of the possibilities in front of us is best done through the power of capitalism, which pushes us to figure out what someone else wants and to give it to them. Even if it’s bad for them (though that’s less explicitly said).

The world grows through the creation of new scenes, and the scenes affect the world through a) internal processing, and b) more integration with the way information flows.

And so, given abundant energy and a larger market the ideas could now collide with each other and people could actually create all the amazing stuff you see around you.

Wherein the true remarkable giant of progress, technology, is unpacked

Hitherto it is questionable if all the mechanical inventions yet made have lightened the day’s toll of any human being. John Stuart Mill

The magician’s trick in DeLong’s account however is an error of omission. In moving the “innovation” behind the ideas of industrial research labs and making scientific discovery mere routine. The lab to make discoveries routine and the corporation to make deployment routine, with globalisation as the lubricant to deploy them everywhere. The what, who and how of progress.

This is a huge deal! Scientific discovery existed for centuries, if not millennia. If you look at the progress of innovations over time, it looks like a steady accumulation that results in an explosion. The explosion is meaningless without an account of an accumulation, since they are of the same trend!

DeLong also thinks about our technological progress post 1945 as a sort of skill amortisation game, where exceedingly high-skilled engineers and designers put in the hard work upfront, which then gets used and amortised by lower skilled machine operators.

This is supposed to have increased the process of outsourcing and offshoring, and in general seeing those who do things as replaceable cogs. However this isn’t true. It falls prey to the notion that the equilibrium was stable before. Rather, almost all corporations, Henry Ford included, wanted to reduce costs and were constantly on the lookout for methods to do so, using both soft technologies (timecards, rotas, production line) or hard technologies (robotic manufacturing and specialised machining) where they could!

There is no simple explanation for why technological progress happened the way it did! There are accounts asking why we didn’t do it before, even for simple things like cycles, and there are accounts explaining ‘twas always thus’, an inevitability. The truth is that no matter how we map the historical progress of technology, we keep seeing things that should’ve been invented earlier but weren’t, and that some things could have only been invented after others.

Whether there is instrumental convergence or convergent path dependency requires someone smart to map out, and here is a good place to start, but we can make some observations in the meanwhile.

Technology is often, if not always, built on top of others

Adjacent possible, as Kaufmann wrote, shows where we might expect new technologies to emerge

We often need to combine multiple strands to create a true new innovation

If you combine all three then you must also answer the question - what if the 1870s were an especially good time for technologies to interplay with each other, such that we could get explosive growth! I know Anton Howes is probably better served to talk about this in more authoritative detail, perhaps in an upcoming book, but until then informed speculation must suffice.

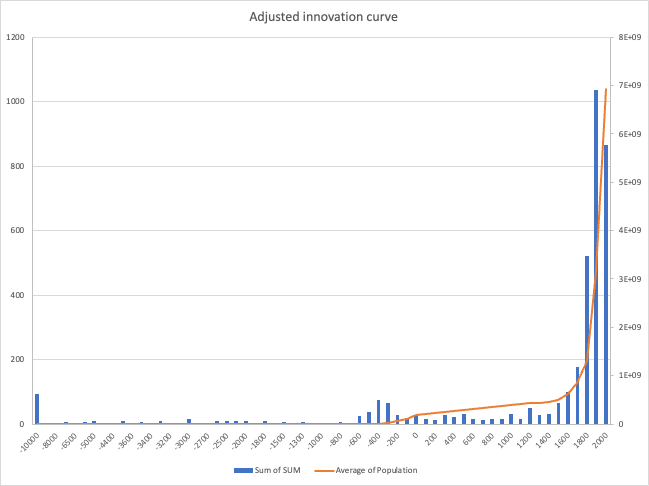

From when I looked at all the innovations I could find historically, across all domains, and mapped them together in one chart. Like so.

And here’s the second one where this is mapped by the number of innovations per year, and the population.

The second is what shows a kink in the curve somewhere towards the late 1800s, as per DeLong’s observation. But the first shows that the growth in the number of inventions was steady.

The prosperity in the 1800s was the result of the work that came before. Once we had machining tools and better communication and global markets to sell into, we could use the economic machine we’d constructed, in the form of capitalist enterprise, to make all our lives better!

… stock of useful ideas about manipulating nature and organizing humans […] shot up from about 0.45 percent per year before 1870 to 2.1 percent per year afterward, truly a watershed boundary-crossing difference.

The question is why this happened. What changed in the actual increase in the rate of increase of stock of useful ideas? Well, new consumers and new producers used old ideas and often new ideas to satisfy their own needs.

Here’s one hypothesis. If all inventors are connected with other inventors, sufficiently such that their ability to create new ideas and inventions are higher, whether due to ideas having sex or because entrepreneurship is a contagious disease, then naturally we’re going to get a higher hit rate. Similarly, if we create large bureaucracies which reduce the speed with which this can happen, for all sorts of well-meaning reasons, it reduces. Or even if it’s because the low-hanging fruit’s been eaten and we haven’t found another pasture nearby!

This could very well be the reason why we might see some slouching and progress towards utopia. But it doesn’t really get covered much in the book.

The Inventor's Paradox

Which brings us to the core exploration that’s missing. Which is the question, if indeed it is technological invention that helps us escape the Malthusian trap, by helping us sell to each other and pull humanity up by its bootstraps, then what took us so long!

We had merchants, inventors, kings with large purses, scenius-style communities with the explicit intention to make cool things, but languished. As we saw we had guilds and funded merchants and explorers and scientific collectives.

The world has always had inventors and merchants. If someone could make a buck by making something for someone else, they would. And they have done this throughout history. The famous story of Crassus cornering the market for fire-fighting services by buying up houses in flames and putting out the fire with his private brigade of slaves should show us that this instinct isn’t something new and emergent in the late 19th century! What did they all lack?

I submit that the century makes a lot more sense if you could look at it from the perspective of an individual, and ask what he needs to reach his potential.

In the year 1200, his potential might have been snuffed out as education was hard to get, resources were hard to get, time was hard to get, which meant the level of extra output beyond survival would’ve been miniscule at best

In the year 1700, his potential would’ve been slightly easier to catch a flame, as education got a tad easier since books existed, time was still hard to get, and resources equally so, which meant the extra output we could’ve expected from him goes up a tiny bit, but not much

In the year 1900, his potential would’ve been much higher, as education was a lot easier, time started being more abundant, resources started becoming available, and the extra output we could expect could’ve then become the down payment for getting the resources!

This gets further complicated based on whether you’re based in colonised Calcutta vs cosmopolitan London. This changes based on whether you’re a black man attempting this in the 1950s US south vs someone in Silicon Valley in the 2000s.

This story of Tesla, for instance:

The year 1881 finds Nikola Tesla working in Budapest for a startup, the National Telephone Company of Hungary, as chief electrician and engineer. But he would not stay for long. In the very next year he moved to Paris, where he worked to improve and adapt American technology, and two years after that, in June 1884, he arrived in New York, New York, with nothing in his pockets save a letter of recommendation from engineer Charles Batchelor to Thomas Edison: “I know of two great men,” Batchelor had written. “You are one of them. This young man is the other.” And so Edison hired Tesla.

But the core of it is that an individual’s attempts to try and do the best they can is what we’ve unlocked through the power of progress. Organisations help, including the industrial research lab and modern corporations. But they’re not sufficient. They are ways we’ve organised ourselves so far, in order to try and make sure that collectively we’re serving that lovely economist phrase - Aggregate Demand - and in doing so enriching ourselves. Enriching not just with money, but with ability and with time.

For instance, the structure of the society revolved around the degrees of freedoms people had. If you look at housewives, DeLong writes:

Perhaps a third of American households in 1900 had boarders, almost always male and unrelated, sleeping and eating in the house. It was the only way for the housewife to bring income directly into the household. It also multiplied the amount of labor she had to do. Much of it was manual.

To get sufficient labour from her required such advancements that she could spend only a few hours in child-rearing per day, rather than the supermajority of her time.

From this lens if we could look at details, we could see how the blockers to an individual's efforts are varied, both positively and negatively through time. DeLong looks in detail at how specific events happened but less about how they changed over the decades or centuries.

We build things that others want, and use whatever we can see around us, and whatever we can create, because in doing so we get richer ourselves

The blocker to this helping everyone is a) the speed of dissemination of knowledge between people, and b) coordinated processing of the new knowledge that came in

When left uncontrolled, the natural state for this enterprise is to end up in is unequal distribution and stasis -> that’s Hayek’s daemon according to DeLong, which Polanyi helps assuage

What could help an individual achieve their optimal success seems to be the right way to approach the question of how we managed to construct a society where we can collectively achieve the optimal success.

For someone to come up with an idea to help someone else requires both an innate sense that this is something they are allowed to do, knowledge of something they can do, and the ability to reach more people once it’s done. If they are also the recipient of more ideas, or indeed enmeshed in the network of others who are thinking similarly as Anton Howes has written, there is an increase in the stock of ideas. If they are part of a larger market they can access, which increases the size of the prize, they are more likely to come up with more ideas and attempt to capitalise on them.

It’s also a narrative that helps put the crazy convolutions that we societally went through in the last few centuries into place. We can ask and answer questions like:

What type of organisations did we stand up and why!

The scientific and technological inventiveness and how they got unleashed

Why did we change how we find, train and reward talent

And the way we can do that is through distilled knowledge. Ultimately we land in the arena of talent creation and education where, as Erik Hoel has written, we’ve chosen mass industrialisation as the method instead of individualised instruction.

Perhaps it was our luck that the conjunctive factors came together, energy, knowhow, talent and material abundance, that together enabled us to conquer this Mammon and step out of our Malthusian trap. But it is the ultimate question that needs to be answered. What does it take to create a scenius? How much control do we have over our surroundings, and how can we create the environment to help foster an increase in our ability to break the slouch? As Tony Freeth writes about the Antikythera mechanism

It was not until the 14th century that scientists created the first sophisticated astronomical clocks. The Antikythera mechanism, with its precision gears bearing teeth about a millimeter long, is completely unlike anything else from the ancient world. . . . As for why the technology was seemingly lost for so long before being redeveloped, who knows? There are many gaps in the historical record, and future discoveries may well surprise us.

Rarely has a book this ensorcelled me in its grip, or thrown up so many avenues of exploration simultaneously. What it reminds me most of is Mokyr’s A Culture of Growth, and Robert Gordon’s The Rise and Fall of American Growth, in both the scope of ambition and the breadth of subject matter covered. Slouching Towards Utopia is a work of political economy, taking us through the long 20th century and explaining the major events. It’s the first audiobook I have ever listened to, and listened to partially with my son. It’s special, you should read it. It has the same quality the best books do - the questions it generates are much more valuable than the answers it provides.

Things fall apart; the centre cannot hold;

Mere anarchy is loosed upon the world …

That twenty centuries of stony sleep

Were vexed to nightmare by a rocking cradle,

And what rough beast, its hour come round at last,

Slouches towards Bethlehem to be born?

What a great review! I love how you point out what the book does well while you also point out its shortcomings.

I'm always suspicious of simplistic explanations of large trends. I'm reminded of a conversation where Frank Oz asked George Lucas why the original Star Wars was such a big hit, and George said something like, "I don't know, man. Why is any big movie successful? You can never predict that kind of thing."

I completely agree with you that capitalism has been the major driving force in improving quality of life. But it's not the one simple answer to everything; it can lead to its own problems when left unchecked (like anything).

I'd love to see you explore how to unleash capitalism in a way that maximizes its positives while minimizing its negatives.

As the great man once said, all models are wrong but some are useful...