TL;DR: In a world of plenty, selection is hard. In a world where selection is hard, we resort to ever more stringent measurement. But if measurement is too strict, we lose out on variance. If we lose out on variance, we miss out on what actually impacts outcomes. If we miss what actually impacts outcomes, we think we're in a rut. But we might not be! Once you've weeded out the clear "no"s, then it's better to bet on variance rather than trying to ascertain the true mean through imprecise means.

Related to Strategy Decay

I.

The year is 1853. You're put in charge of recruitment of officers for the Civil Service. You have to figure out the best way to find those officers who will make the empire proud. They need to understand history, diplomacy, basics of business and economics, languages and generally be appropriate to represent the Empire!

So you decide to create an exam. That's the only way to stop the Duke of Worcestershire from trying to get his saucy nephew a spot, and to make sure the corps isn't complete garbage.

The exam is an unqualified success!

But over time, as people learn that the exam is a success, the pool of applicants grow! Instead of using it to weed out those clearly unsuited and hiring the top 10%, now you're forced to weed out almost everyone and hire the top 1%.

Is the exam still a success?

That's the question we face today too, pretty much across academia, industry, media, finance, seemingly everywhere.

For instance these days, there is the constant hunt from technology companies galore to hire the 10x engineer.

And finding a 10x engineer apparently requires finding someone who hates meetings, knows every line, documents in their sleep, thinks in code, and doesn't job hunt. Or, more prosaically, finding someone who has perfect scores in STEM and therefore has the aptitude and interest to be great. Turns out Google crunched the numbers and in their top employees, STEM expertise was dead last.

Or, let's look at yet another case. The IIT entrance exams in India are notorious. They hold the key to getting into the prestigious Indian Institutes of Technology, which is one of those inflection points Indian parents salivate over. 1.2 to 1.4 million students write this exam every year, which has grown about 3x since the days I took it a decade and half ago. The pass percentage has come down proportionally, and is 0.9%, despite increasing the number of slots dramatically. Harvard admission percentage, for comparison is a stately 3.4%, out of 40k applications.

To give you a sense of how insane it is, there is an entire city in Rajasthan, a decent sized state in a very populous country, dedicated to bringing students in every year purely to prepare them for the entrance examinations.

How many students? 150,000 every single year. That's an economy of half a billion dollars. In India where the per capita income is $2k. A significant percentage of these students actually take an entire year or more out of their school to focus on the entrance exams.

So, clearly the exam has utility. There has to be a way to select the top echelon of students to study at the most elite institute in the country. But is the exam actually helpful? How do we select the best?

The reason this is important is self evident. Hiring the best is an incredibly important decision, perhaps the most important, for pretty much everyone. This holds true for creeds as wide as Tyler Cowen and Steve Jobs.

II.

In any examination there is an average mark that a student will get if she wrote it, say, ten times. Let's call that their true mean. In any individual examination there's also a chance of her either screwing up or doing crazy well. That's the variance. In most exams, if they're one-offs, you want to ideally find the true means and minimise variance.

As long as the selection process is coarse-grained, we're primarily focused on saying no to clearly bad candidates and taking in a reasonable proportion of the borderline ones in case they shine later on!

In that case, if you're a top candidate, you're allowed a bad day. And if you're an average candidate and have an exceptional day, you get to get lucky.

But as the percentile you're taking gets small enough, the variance takes centre stage. Suddenly, having a bad day is enough to doom you. An average-but-capable candidate can never stand out.

But it has even more insidious outcomes. It means everyone now must make like slim shady and focus on their one shot, one opportunity, to actually make it.

And since no exam perfectly captures the necessary qualities of the work, you end up over-indexing on some qualities to the detriment of others. For most selection processes the idea isn't to get those that perfectly fit the criteria as much as a good selection of people from amongst whom a great candidate can emerge.

When the correlation between the variable measured and outcome desired isn't a hundred percent, the point at which the variance starts outweighing the mean error is where dragons lie!

III.

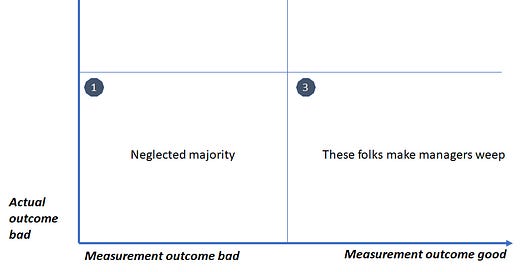

What we actually want is folks who are good at some desired trait. And we use our measurement skills (exam, interview, good looks) to find them. But the problem is that quadrant 4 is tiny, and it gets tinier the more variables there are.

If everyone was equally distributed, that means that after carefully weeding out Quadrant 1, you'll end up with maybe a 50% ratio of folks who are actually good at the outcome desired.

But now imagine if that grid was a cube, suddenly you'll start to only see 25% who are actually good. And so on and on for new (truly independent) variables added.

This means that for almost every system, trying to increase your measurement accuracy only gets you so far, and its much better to reduce the accuracy and increase the variance.

Our attempts at more precisely measuring what we can is landing us in the uncertainty principle world where we're less and less getting what we actually need.

Scott Alexander had an old post that tried to use the "tails diverge at extremes" theory as an explanation for the difficulty we have in finding moral systems that work in extreme scenarios, like figuring out what system of morality we should imbue our imminently arriving artificial general intelligence. It referred to another Lesswrong post which discussed the phenomenon.

It explains why even when two variables are strongly correlated, the most extreme value of one will rarely be the most extreme value of the other.

I had explored something similar a while back, where I'd argued that the systems we'd developed to intuit our way through our lives have difficulty with contrived examples of various trolley problems, but that's mainly because our intuitions work in the 80% of cases where the world is similar to what we've seen before, and if the thought experiment is wildly different (e.g., Nozick's pleasure machine) our intuitions are no longer a reliable guide.

It points more broadly to the phenomenon known to all (or at least all statisticians) as Berkson's Paradox. For instance, if you look at the correlation of attractiveness and talent, it might look positively correlated in the overall population, but negatively correlated amongst celebrities.

Or, hypothetically, if you were to analyse how endurance trends within athletes, you might see a negative correlation of aerobic ability to strength, even though within the broader population the traits might be positively correlated. Or.

The idea is this: when a sample is selected on a combination of 2 (or more) variables, the relationship between those 2 variables is different after selection than it was before, and not just because of restriction of range.

A similar effect is also seen in this article by Malcolm Gladwell about the talent myth - about the difficulty of identifying talent, in the context in this case of recruiting NFL quarterbacks.

This is the quarterback problem. There are certain jobs where almost nothing you can learn about candidates before they start predicts how they’ll do once they’re hired.

He wrote about the NFL quarterback selection process, how rigorous it is, and how it spectacularly fails quite often. The insight is that the only comparable to playing in the NFL is actually playing in the NFL. In other words, the correlation of the factors the coaches were assessing and actual performance in the sport was much less than 1.

The answer Gladwell gives is that we need to change our thinking from a selection mindset (hire the best 5%) to a curation mindset (give more people a chance, to get to the best 5%).

IV.

Its instructive to ask how this problem started happening in the first place. Both the civil service, and Harvard admissions, and NFL quarterback recruitment, and engineer hiring, were relatively understood problems.

But over time, as the pool of candidates increased and the number of spots didn't concomitantly increase, and now we're be left with an enormous job of selection. He can read 1500 applications and make quick judgements, perhaps, but what about 15,000? 150,000?

A casualty of success is scale. And a casualty of scale is that we are forced to create new gating mechanisms to solve our problem of plenty.

So why do we create ever more complex and strict hiring criteria? Because we have to. In the days when you needed to hire 1 out of 20, you could scale it up to 4-5x, even 10x, before you lost your mind.

But what happens when that becomes 1 out of 100?

And this isn't just because our economy is growing? Yes, this is partially true. Or because globalisation means that there are more candidates for each position? Also true. But its also because we've now created a liquid enough market for most jobs that applying to them isn't the hard bit anymore (see What is a job section of Understanding Wage Stagnation), but its rather the effort needed to select from amongst the applicants.

If there are 10 jobs our there and 10 candidates, and they all apply to all 10 jobs today (hi, internet) vs applying for only 2 that were in the same city before, each company suddenly saw their selection effort go up 5x.

And when the selection effort 5x-es, the company doesn't usually go "whelp, guess I better spend more energy interviewing", they go "what criteria can I use to weed this insanity down? I need a frickin coffee I'm so exhausted".

And you start hearing stories about "I could never have gotten into Goldman today," or "the kids are so much more accomplished today than I was at their age," or "a majority of our engineers were former founders."

Alexey et al, for instance, has written about the fact that not all researchers are equal, which makes researcher productivity hard to measure. Well part of the reason could be that along with institutional sclerosis and scope creep, we are also putting folks through a selection process that reflexively moulds them into rule following perfectionists rather than those who are willing to take risks to create something new. In fact more of the major scientists make a point of saying how they wouldn't even get hired these days, much less be in the running for Nobels.

V.

There are two major problems to scale - one is the problem of discovery, which I talked about here regarding the creator economy and how it encourages power laws.

The solution to the problem of discovery is better selection, which is the second problem. Discovery problems demand you do something different, change your strategy, to fight to be amongst those who get seen. Selection problems reinforce the fact that what we can measure and what we want to measure are two different things, and they diverge once you get past the easy quadrant.

The solution to this problem of plenty is to actively stop narrowing the funnel. You could either increase the predictive value of your measure (better exams, new interview techniques, hiring from Twitter), or you could enforce the higher variance strategy of hire-and-train.

Tony Kulesa's great piece at identifying one of the best talent curators of our time, Tyler Cowen, mentions a strategy he seems to implicitly follow. It seems to refer to just such a "high variance" strategy.

Gladwell thinks that the answer is to look at recruitment more like the Marine Corps does - focus not so much on the incoming qualifications, but rather look at recruiting a large class and banking on attrition to select the right few.

However that's a lot more extreme. Despite Berkson's paradox we can still say something about the direction of causality. We can't distinguish amongst the top 10% is a vastly different outcome to we can't differentiate amongst the top 30%. We can still weed out those who will, pretty clearly, be unsuitable. This is what investment banks and consulting firms do. They hire a large group of generically smart associates, and let attrition decide who is best suited to stick around.

Our hiring criteria holds still to a notion that relies on smaller pools and easier assessments. As the numbers increase you add more gateways - an exam, a personality assessment, a case study, an interview. Problems caused by measurement errors can't necessarily be fixed by even more stringent measurements.

And this applies to a wide range of efforts. You want to get better investment returns? The answer is rarely to get even more stringent with your diligence efforts.

I don't have a pithy solution here, beyond the fact that we should at least recognise that our problems might be stemming from selection efforts. We should probably lower our bars at the margin and rely on actual performance to select for the best. And face up to the fact that maybe we need lower retention and higher experimentation.

It isn't a great clarion call, but the only solution to scale issues is to try radically new structures and find a new process that works. Don't try to predict success, but enable it. Lower your standards, ye hiring managers, and let your people go!

As an software engineering leader this comment almost perfectly describes what Ive seen " Well part of the reason could be that along with institutional sclerosis and scope creep, we are also putting folks through a selection process that reflexively moulds them into rule following perfectionists rather than those who are willing to take risks to create something new. In fact more of the major scientists make a point of saying how they wouldn't even get hired these days, much less be in the running for Nobels." I believe that the 10x engineer is very comfortable taking risk and occasionally failing and the process seems to beat that out of the most successful candidates

This is going to be one of my favourites, alongside Strategy Decay and A Study of Eccentricity.

Because it's something I've recently been thinking about + advocating for. Which brings me to my first question: Is there any obvious reason that "The Economic Costs of Entrance Exams" would not be a good research topic?

The costs in question being primarily oppurtunity costs (delayed employment for potentially productive citizens, overly-homogenized knowledge among candidates after years of preparation) as well as financial (cost-benefit of money spent on education). I've been told that it wouldn't be the easiest thing to analyse. But then again, I'm not above making non-rigorous arguments when I want to.

IMO the better you are at something, the more of an oppurtunity cost the practice time for tests is. Honestly disappoints me how the benefits of post-scarcity (people can crash more often and not die) end up being nullified by a combination of lifestyle creep + status.

Re. 10x engineers, I'm sure you've heard of the possibility that they're not all that great for the company as a whole (here's a link for the comment readers: https://www.hillelwayne.com/10x/ ).

Particularly interesting to me is the idea that maybe some fields lend themselves more to "top 10% and consistent/colabborative and y'know, actually hireable" vs. "top 1% but incredible". The popular concensus (esp. in software) seems to be the latter, but I'm starting to suspect that's (at least somewhat) wrong.