Strategy Decay as an Institutional Problem

A meditation on using "shore up the bottom" strategies as we scale; which is qualitatively different to actual "winning" strategies

I

In many cases there is a clear argument that's laid out something like this. "Group A took these actions. They perform better than the average. Therefore we need to learn what they did."

Sarah Constantin had a great bit of analysis recently on what's needed to attain better than average performance. Her conclusions:

Overall, engaging in more research into company fundamentals, and being in some sense “better at formal analysis”, does correlate reliably with higher returns

It's well worth a read. The interesting aspect is how low the bar seems to be in some ways if you're an aspiring money manager. Which in itself is insane!

While her analysis does show highly suggestive directional results though, it also includes this:

Strikingly, the biggest downloader of public financial documents is Renaissance Capital, whose 66% annual returns over the past 30 years dwarf anything else in the financial markets.

It's worth saying Renaissance Capital is the master of ingesting vast quantities of data and running algorithmic analysis on it. As Jim Simons, the Chairman and founder, mentioned in his congressional briefings, they don't even know what stocks are held or traded in the fund at any time. As a quant fund, their idea of "due diligence" is vastly different to that mentioned in Sarah's blog.

This is an important point, and we'll come back to it later.

But the first and most important point is that there is a way to become better than average at something, and that is to do the basics. What are those basics? Sarah writes:

Hedge funds that make more in-person site visits to portfolio companies have higher returns. Site-visitors have annual returns 6.1 percentage points higher than non-visitors. Investment firms that download more SEC filings have higher returns. Downloaders (of any files) have annual returns 1.5 percentage points higher than non-downloaders. Financial analysts who download SEC filings make more accurate forecasts than non-downloaders, and the longer they spend reading SEC filings, the more accurate their forecasts. “Buy-side analysis” refers to the research and forecasting performed in-house by employees of investment firms. Mutual funds whose investment decisions more closely track the recommendations of their analysts have higher returns. Angel investors who do more due diligence have a significantly higher proportion of their investments become “home runs”, defined as investments where the investor receives returns of at least 100% upon exit of the company.

Hopefully you can see how simple these observations are! None of them are asking for much more than performing your fiduciary duty.

The takeaway from this is striking: Most investors, including professional investors, seem incredibly lazy, in that they don't even do the bare minimum you would expect them to.

And therefore doing something as simple as visiting the sites of portfolio companies, or downloading the latest publicly available data, or not just copy-pasting the analyses from others, have outsized returns.

There are a whole bunch of methodological questions here of course. Just to get them out of the way:

Site visits seem important come from research in China. Applying that to developed markets, where information isn't as hidden, might not be applicable

Fund manager's risk tolerance measurements, done through a Cognitive Reflection Test, might only capture point in time differences

The size of the fund in question might change your strategy and your behaviour. If you're running a $10B fund, you have the resources to gather the best data and run analyses, while the smaller minnows might just be shooting in the dark in the hopes of striking something

With all those caveats, there's a critical question here. This seems like pennies strewn about on the side of the road. Why aren't they getting picked up?

I mean any hedge funder would love to add another few percentage points to their haul, and all that it costs is to do some basic research?

What's wrong with this picture?

II

But financial services is not alone of course. There's a voluminous literature about the importance of doing seemingly small interventions and getting outsized returns from it in other areas too.

Example, Atul Gawande, in his fantastic book The Checklist Manifesto, describes the benefits of those seemingly simple interventions. Malcolm Gladwell's review of his book states:

Gawande begins by making a distinction between errors of ignorance (mistakes we make because we don’t know enough), and errors of ineptitude (mistakes we made because we don’t make proper use of what we know). Failure in the modern world, he writes, is really about the second of these errors

Pilots and architects have checklists and written guides to walk them through the steps in any complex procedure. In healthcare, the results are well known.

It's yet another case of a set of seemingly simple interventions that had outsized returns.

“So it seemed silly to make a checklist for something so obvious.” But Dr. Pronovost knew that about one-third of the time doctors were skipping at least one of these critical steps. What would happen if they never skipped any? He gave the five-point checklist to the nurses in the I.C.U. and, with the encouragement of hospital administrators, told them to check off each item when a doctor inserted a central line and to call out any doctor who was cutting corners. As Dr. Gawande relates it, “The new rule made it clear: if doctors didn’t follow every step, the nurses would have backup from the administration to intervene.” The nurses were strict, the doctors toed the line, and within one year the central line infection rate in the Hopkins I.C.U. had dropped from 11 percent to zero.

And while they had to be shoved down the surgeons' throats, the administrations quickly ensured that they were followed. The nurses were authorised to step in and force their hand. And the steps were taken.

And the actions had the desired effect. The averages of mistakes made went down. As the strategy, easy to understand and implement as it is, percolated through the medical community, its impact became clear. The bottom was shored up, and mistakes that were routinely being made were avoided.

But what about the 33% central line infections remaining in the ICUs in Michigan? We have to find new strategies or methods to solve those. This is not at all to reduce the genius in the idea. Finding a trivial method that saves thousands of lives is the equivalent of someone picking a stock and becoming a billionaire. It's a needle in a haystack. From a NYT article:

One item on the pneumonia checklist — that antibiotics be administered to patients within six hours of arrival at the hospital — has been especially problematic. Doctors often cannot diagnose pneumonia that quickly. ...So more and more antibiotics are being used in emergency rooms today, despite the dangers of antibiotic-resistant bacteria and antibiotic-associated infections. ... We know that heart failure should be treated with ACE inhibitor drugs, but codifying this recommendation in a checklist risks that these drugs will be prescribed to the wrong patient — a frail older patient with low blood pressure, for example.

These might be seen as trivial outliers, or symptoms of the lack of flexibility engendered by firm adherence to a pre-approved strategy. It's worth seeing what we're talking about here. We're not looking at checklists to solve hard medical problems. They are not increasing our peak efficiency. They are not making the best of us even better.

They are creating a floor beneath us by preventing dumb mistakes from taking over. One way to push up the average is by creating a floor, and that's what this strategy does.

III

Both types of arguments in parts I and II are essentially focused on the simple strategies that one needs to do to push performance above the median. By following the tenets of those well understood maxims you eliminate a source of information discrepancy in the market. Once The Intelligent Investor got published in 1949 and applied by Warren Buffet, it's applicability today has become limited.

Even when you consider technical analysis, either considered a sophisticated method of reading the mind of Mr. Market, or considered a fool's way of reading patterns where there are none, went through the same process:

Some aspects of technical analysis began to appear in Amsterdam-based merchant Joseph de la Vega's accounts of the Dutch financial markets in the 17th century. In Asia, technical analysis is said to be a method developed by Homma Munehisa during the early 18th century which evolved into the use of candlestick techniques, and is today a technical analysis charting tool... In 1948, Robert D. Edwards and John Magee published Technical Analysis of Stock Trends which is widely considered to be one of the seminal works of the discipline.

Efficient markets don't become efficient through osmosis. It requires someone to do work to bridge the information differential enough that the systemic ability to get alpha goes away. In other words, these "inefficiencies" are how the overall efficiency increases in the market. Still, the fact that there are these golden tickets lying around is suspicious. That's not supposed to happen.

People who manage money, not individual amateur investors, shouldn't be ignoring the financial equivalent of a checklist to make more money. But they do.

But now, what about those higher up in the distribution? How do you move from top quintile to the top decile? Do they do something different?

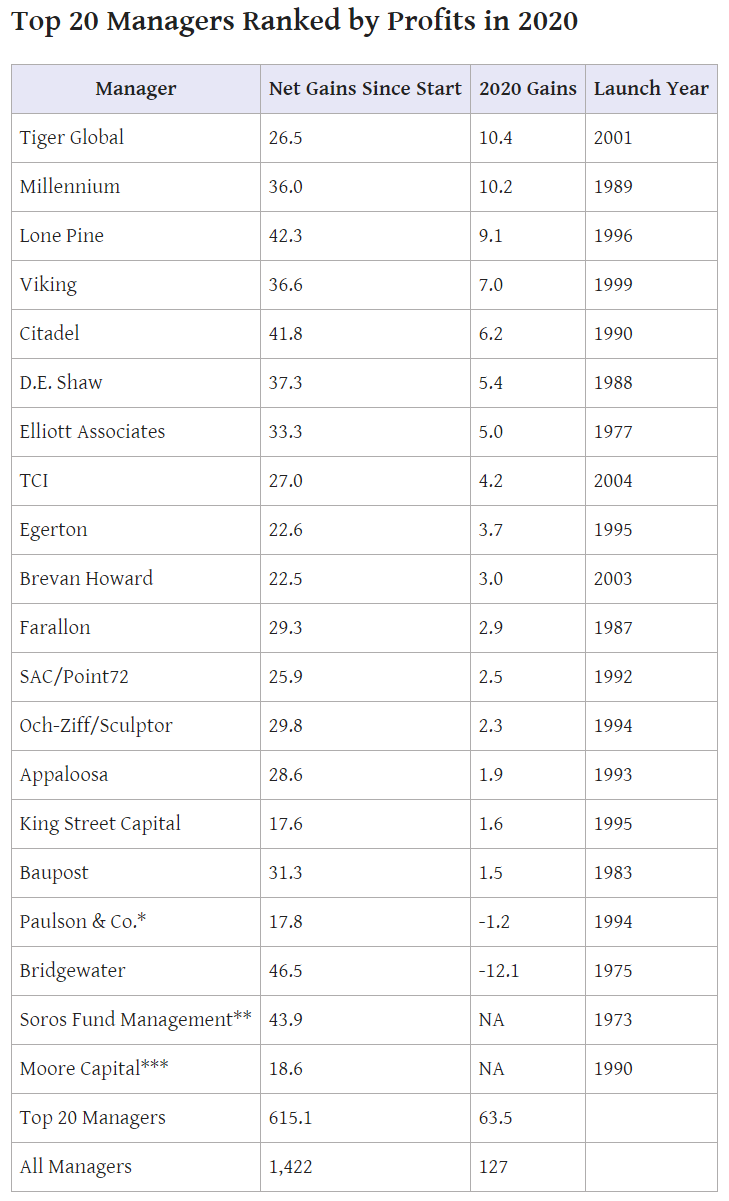

Let's have a look at the top performing hedge fund managers in 2020.

What is interesting here is not just the breadth of launch years, but also the breadth of strategies amongst these top managers. There is fundamental, quantitative, investing in private markets, long/short, and their combinations besides. All of these managers put inordinate resources into identifying and recreating its strategies, and that is complex enough and secret enough that it's their entire IP. That's why Bridgewater, the world's largest hedge fund, sued its former employees (and lost). Or why Citadel sued its former executives when they set up their own firm.

And things are complicated here, at the top of the curve. For instance, this paper from University of Chicago suggests that even when market experts overperform in buying decisions, they might still underperform in selling decisions, performing even worse than random. It just goes to show how difficult it actually is to create a strategy to win. Often as not it's misleading, since you don't know it's the strategy until you win, remaining a hypothesis or an experiment until then. When ARK became the darling hedge fund in 2020, that came off the back of a decade of neglect.

Or look at the VC world, where contrasting the top performing Andreesen Horowitz and Benchmark Capital shows a vast gulf in strategy. One is trying to recreate a useful back office for every company they back, almost like a combination of a consulting firm and a university, while the other, intentionally, does nothing. One has employees in the 100s, and the other has its 6 partners.

The rule in VC, and indeed in most investing, and probably in other areas of life too, is what Marc Andreesen says about needing to be contrarian and right. You have to find a secret (Peter Thiel) and you have to be right. They're all suggesting new ways to find strategies to win.

On the other hand when 500 startups has Dave McClure write about the benefits of a high volume portfolio in getting power law returns, that's a strategy to shore up the bottom.

At the top of the distribution there is a furious fight amongst highly sophisticated strategies to see which one will win out. That's where the smartest ideas compete against each other to get outsized returns.

As a strategy wins out and becomes more and more common, its marginal benefit grows lesser and lesser. When VCs started realising the power of the power laws and started backing whole portfolios the game changed, vs when they used to sit on the same board for multiple decades.

What used to work before doesn't work anymore. This is strategy decay.

When you are trying to move up the average by shoring up the bottom, this problem doesn't apply. But when you are trying to move up the average by fixing the top, this very much applies.

In finance and investments, doing the basic work is essential to move up above the average. But that's only the case because of the large percentage of investors who don't do the basics, leaving the strategy to shore up the bottom still useful.

Once they do however, it's like the aftermath of implementing the checklist manifesto. You cannot improve much over the average. But unlike in healthcare where you're avoiding catastrophic outcomes, there's no equivalent in investing. It's not like everyone will end up with double digit annual returns. That's when you need to move beyond the basic strategies that are employed to shore up the bottom to dedicated ones to help succeed at the top.

IV

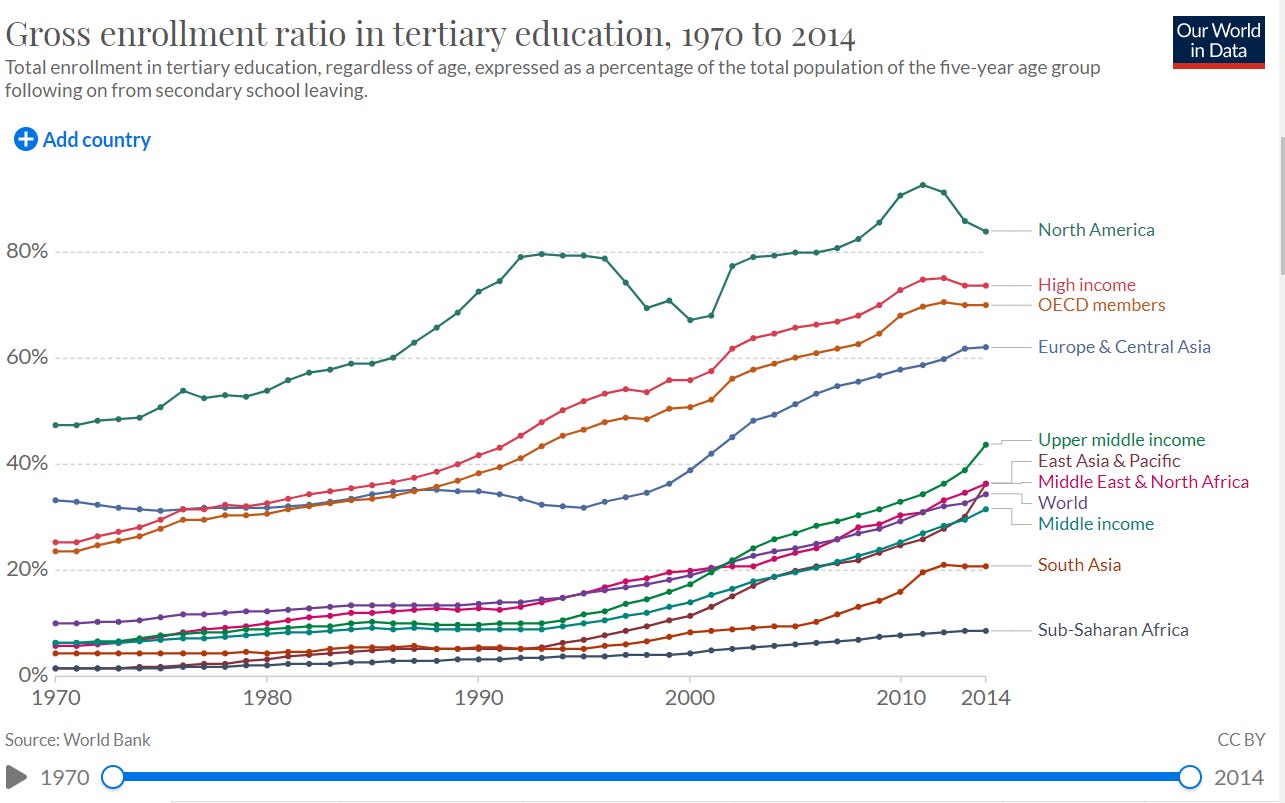

With this lens, let's take a look at a different problem. What's widely considered to be a ticket to a better life, a university education. Since the monocausal event in 1970, the enrolment has doubled in multiple high income countries.

And along with this we have seen a decrease in the satisfaction of students enrolling in the universities. And there are journal articles about the declining value of college going. Let's look at the evidence.

If it's regarding getting a job, Tech giants such as Apple and Netflix no longer require you to have a college degree

And at best, maybe 20% of your classes have anything to do with what you'll actually do in a job

But still, it is widely considered to be the best investment you can make.

There’s no better investment return than college – not even close. Long-standing economic analyses have shown that people who earn a bachelor’s degree – on average - make considerably more money over their lifetime than those with a high school diploma. And according to researchers Michael Greenstone and Adam Looney, an investment in a college degree delivers an inflation-adjusted annual return of more than 15%, significantly larger than the historical return on stocks (7%) and bonds, gold and real estate (all below 3%).

This is now received wisdom. From the New Yorker:

But what bubble believers are really saying is that young people today are radically overestimating the economic value of going to college, and that many of them would be better off doing something else with their time and money.

From Brain Pickings

Given the dramatically changed circumstances grads today face, we already know that the trends for debt, employability, and the value of a degree have all degraded, and we cannot assume the trend toward greater lifetime earnings will hold true for the current generation

But what if the gain is non-monetary, in that you gain a strong network? That is true, but also only amongst the most elite top tier colleges. It matters much lesser for those further down in the university rankings totem pole.

It's not just in college, even a recent Atlantic piece on the elite private feeder schools says the same.

More than 50 percent of the low-income Black students at elite colleges attended top private schools

Clearly there is an argument in favour of the top, elite institutions as they engender not just strong education but impeccable signalling and a way to buy into an ingroup that you might not have access to otherwise. But it's also the case that this, by definition, is a dynamic strategy that will not survive if everyone did it.

It's anti-Kantian in that sense - the rule only makes sense if a very small number of people put it into practice.

Could it be that the simultaneous increase in tertiary education and decrease in its efficacy is a case of strategy decay? Yes of course it is. When you are a college graduate and that's relatively unique, your value is much more visible than when everyone is a college graduate. That drives flight to quality re top institutions, grade inflation and price inflation, starting right at the top.

This is as clear a case of a previously applicable strategy gone awry as exists. There was a clear line of action which would help those who did it break into the middle class and beyond. But it only worked when everyone else wasn't doing it. Once it became known that this "ticket to golden life" existed, its value decreased.

V

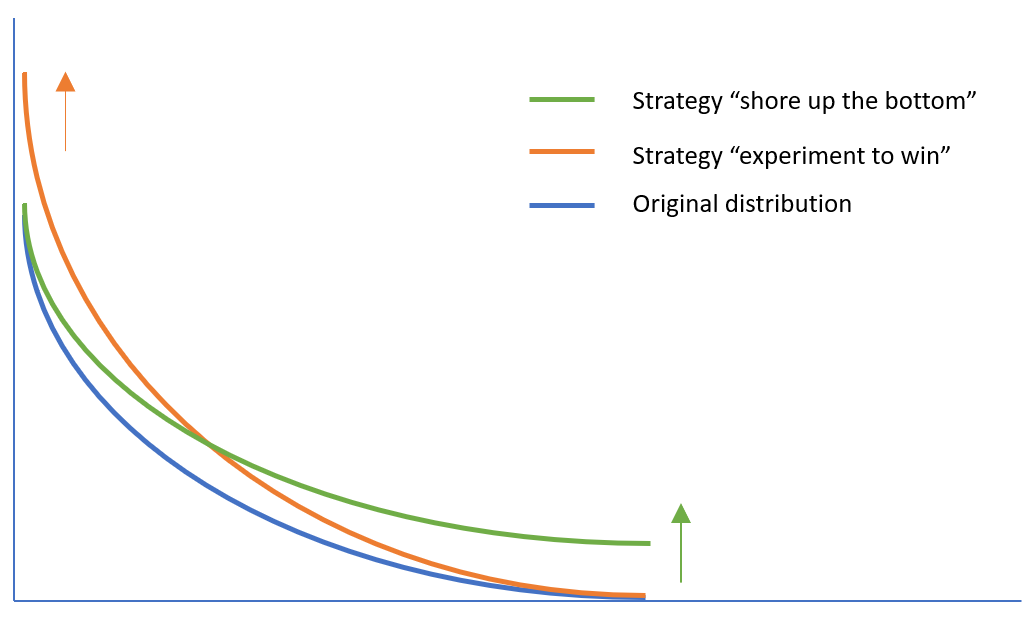

This also tells us about which strategies work where, which is one of the biggest source of controversies in the most arenas, because they are often in conflict. Most well meaning policies offered either focus on pulling up the top of the distribution (the orange line), or pushing up the bottom long tail (the green line). Both of them help improve the average performance, though the orange one does more than the green.

The difference is that the shore up the bottom strategy tries to push the entire curve up but mainly works at the long tail. The other is what's used amongst the top quintiles and deciles, which help push up the top end of the curve. And the strategies they make eventually trickle down and become common knowledge, and once diffused stop being sources of alpha.

Most pieces of advice in management or consulting lay here. They benchmark and identify ‘weak spots’ and argue for specific interventions, all to make the market more efficient. They equalise the playing field and ensure there isn't much "obvious inefficiency" remaining in the system.

It's a fight between the "shore up the bottom" strategies to equalise the curve while the "experiment to win" strategy focuses on finding new ways to push through, new inefficiencies that change and morph the distribution. That’s where innovation lies. In the interplay amongst these two lies all the riches of the world.

VI

We want our institutions to do things that have mass applicability. We need those strategies that are easy to communicate and that everyone imbibes as sensible. Which almost by definition means we rely on institutions at scale to apply the “shore up the bottom” strategies, to bring up the average, while we rely on individualised “experiment to win” strategies to help bring about innovation.

Whether it's the political third rails of minimum wage hikes or free college tuitions, the "shore up the bottom" strategy is aimed at helping bring about equity. But the over-reliance on the shoring up strategy makes it entirely focused on solving the catastrophic problems, but since there is very little reliance on an actual strategy to win, the older "equity" rules just end up ossifying on top of each other.

When we are annoyed at schooling, or “child prisons” as some call them, we’re asking why these “shore up the bottom” strategies don’t also provide room for innovation and humanity. It’s an incoherent question.

When we tack on rule after rule to the FAA and FDA and CDC and others of its ilk, we're shoring up the bottom. But as time passes on those decisions ossify and end up obstructing any ability the organisations have to get things done. The focus they should have had in pushing the curve up, the strategies to win, get no discussion or attention.

So we debate checklist strategies to push up the common ground, prevention strategies for accidents, and underinvest in things that bring true change.

The problem with overusing the Efficient Markets or Outside View is that the averages and variance become similar. Someone needs to create the alpha.

That’s why we can't all be passive investors. That's a strategy that's only worthwhile to mention because most people don't follow it. That's also why we can't all get personalised insurance, for that matter.

There was a time when owning a home was a great strategy for wealth creation. But now that everyone is doing it, the market has corrected and the strategy doesn't apply any longer, it has decayed.

So essentially the options boil down as the following:

At the top quintiles of the distribution, there is a fight to find different strategies to win, to eventually find one that works

Once a strategy wins out at the top, it percolates down to the rest, and becomes well known

These end up being strategies that are focused on shoring up the bottom, which might help stop obvious problems to push up the average

This ends up being well known because they are simple, and legible, and credible

However once the "common" advice is taken by a large enough populace, it decays, and stops working nearly as well

The "common strategy" remains, through inertia I suppose, as our collective understanding of what the right thing to do is

Going to college is one of those types of strategies that seems to have stopped working.

Health interventions, similarly, is another one of those where the strategies don't seem to add much value. Now that we've stopped smoking so much the next low-hanging common strategy seems to be to eat better and exercise.

Investing in technology companies too seems to have been one of these strategies over the past decade (and more). You invest at seemingly crazy valuations but the companies keep growing! Can you still do that in 2021? Probably not, because the strategy has now decayed.

So should everyone just invest in low cost index funds then? I used to think so, but now I'm not so sure. 1) If they do, then the market collapses. And 2) I don't know that substantially increasing the number of people indexing will necessarily decrease the volatility of the market. In fact we might be giving up some nuggets of information that someone has in a corner of the market that just never ends up surfacing.

In Eliezer Yudkowsky’s book, Inadequate Equilibria, there is a portion towards the end where he argues against overusing the Outside View (broadly equal to believing the consensus) when you have reason to believe that you are smarter than the average in that particular subject/ domain/ way of thinking.

In some ways this is true, but I'm not sure how to put it into practice. If I knew I was above average at something then I could use it. But I'm using my faculties to think I'm above average and they might be wrong. While there are clear areas where you can perhaps track them using predictions and so on, this doesn't seem to happen very often! It becomes Chesterton's Fence gone awry, taking the "world as it is" with all the sense that Voltaire had when he called this "the best of all possible worlds".

The advice we get often falls into this trap, of believing the world is more efficient than it is, and best we can do is to shore up the bottom. We think we're getting strategies to win, when in reality we're actually getting the common strategies to climb above the median. Whether from the institutions in times of crisis (hello CDC during a pandemic), or from our financial gurus (60% stocks 40% bonds, invest in Bitcoin, Index always), or a startup idea (isn't payments over?) this is an endemic problem.

Most standards and certifications and mandates fall into the shore up the bottom camp. That’s what they’re designed to do. Failing them for not solving for innovation is changing the goalposts. When we blame institutional effectiveness for not promoting innovation, we’re trying to unify the two, which is often a fool’s errand. Recognising that there are these two completely different strategies should help, and recognising that there is a strategy decay we need to watch out for is essential.

PS: Going way out on a limb, in some ways I feel looking from the outside, this might even be part of the magic of the US. There is a firm belief in fighting against the Outside View, even when it seems eminently sensible, like with accepting public healthcare. Which seems obviously stupid and counterproductive, but perhaps they're doing the hard yards at the top of the distribution so that the rest of us can invest in index funds and reap the rewards.

> If I knew I was above average at something then I could use it. But I'm using my faculties to think I'm above average and they might be wrong.

I find it fascinating the extent to which this mindset has permeated the rationality/effective altruism communities (despite admonitions from people like Eliezer). It's just not that bad if you sometimes think you're above average when you're not! As long as you course-correct quickly you'll be fine.

I think the problem here is that most people's typical thought processes are broken in *multiple* major ways:

1. We are tremendously overconfident and update too slowly on new evidence;

2. We are pathologically afraid of doing things that go badly, so require way too high of a bar of confidence to act on.

It's easy to demolish 1 for yourself by reading the right blogs; it's much harder to demolish 2 because it requires actually going out and doing things (while getting advice from people who are good at avoiding 2).

Amusingly, 1 and 2 sorta roughly cancel out at the 30,000-foot level, so demolishing only one is actually maladaptive. The result is a bunch of people who are great at noticing people being dumb, but in a way that is actually neutral/negative for their ability to go out and do things.