I

Study of persuasion within social networks show that there is a considerable number of articles, scholarly essays, and academic papers written about the process of information (and disinformation) dissemination within social media circles. There's analysis on who gets impacted by the various choices presented to them, how they take in information presented to them, how to identify the veracity of news, which factors influence credibility, and how this differs from platform to platform.

Lest the article be entirely filled with blue lines, one thing that seems undertheorised however is the how we should think about the new paradigm that we're living under. If you ask people where they get their news, the answer seems to be social media. If you ask them where they talk to/ discuss with/ interact with/ socialise with their friends, the answer is also social media. If you ask companies where they find their customers, the answer remains the same. It seems that any path to persuasion has to contend with the unique dynamics of the mechanisms of persuasion we have at our disposal.

First, it's not just the speed or frequency of updates that's new. Londoners in Victorian times used to get newspaper delivery 12 times a day. Not only would you get it this often, you had to pay postage for the privilege of number of sheets of paper and the mileage. The best assessment of what this world has to deal with was of course written by Sir Terry.

But one thing is different now. Unlike getting post delivered 12 times a day, we get alerts multiple times a minute, or second. A difference in scale, if not scope. It also doesn't spread one-to-many, with a centralised media pushing similar content to multiple people, but very many disparate sources of information creation and dissemination. Almost as if the journalists were all embedded amongst us in society.

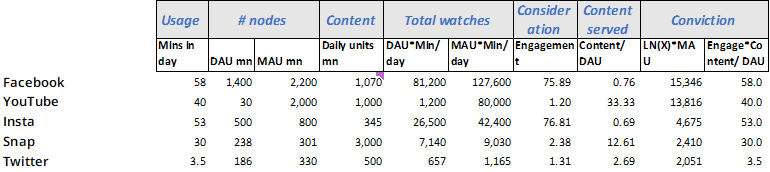

I wanted to have a look at what is it that affects the disinformation transmission. We speak of the usual suspects in the same breath (Facebook, Twitter, YouTube) but I've always seen them as completely different things. As dangerous as it is to extrapolate from personal experience, my usage of all three, and the information I get from all three, seemed disparate enough that lumping them together seemed like a bad case of generalisation.

So I tried to build a few simple models to test out my theory. People would read, watch and engage of Facebook posts, they would tweet, retweet and like on Twitter, and they would watch videos on YouTube. In doing any of these activities, they might get a piece of information. I leave aside the provenance of the post/video/tweet, since there is a meta-heuristic that most people apply to their information consumption. You're after all more likely to believe something if your friend posts it rather than a complete stranger. But that's a complication for another day.

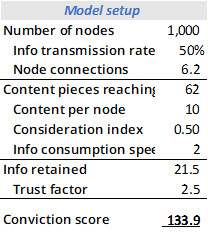

At a basic level, the thesis is that you get convinced if you get enough pieces of content coming to you, that you consume fast, and if they take enough time to simmer in your mind. Some multiplicative property that combines the factors help make up a conviction score. For an individual, conviction is built from number of content pieces coming to you * time you take to consume it * time you take to think it over * trust factor of content. Yes, there are modes of information to be spread that has self-referential properties, i.e., the fact that something is popular makes it easier to accept. The individual parts here all rely on each other in rather complicated ways.

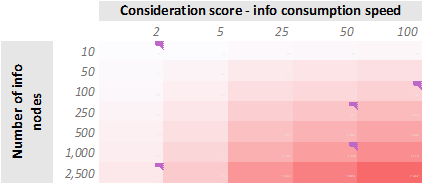

First, the results comparing two key variables - the size of the network or number of nodes in the network, and the information consumption speed, a proxy for consideration score, i.e., how carefully do people consider the information presented to them.

Link to the spreadsheet - https://docs.google.com/spreadsheets/d/1HRkQupFiVqcAfuTY-n-_XDGyKrVAOjEr5q6ZTQi69F4/edit?usp=sharing

A few observations. First, rather obviously, the larger the network the more it impacts your conviction levels. Also, the faster you consume content, the more you get convinced, mostly because this affects your ability to find more and engage more. So does it matter if the network itself is large? Only insofar as there are more vectors that could point to you and bring info. Does it matter if the speed is high? Yes, if it means more information turnover, and less time to explicitly consider and consume.

Also, there are clear catalysts. If Mass Media sets an agenda topic this moves the conversation to areas where it can find high engagement, and seeds the conversations.

On YouTube, where there is more time spent in content being consumed, trust factor is medium, and content seen per viewer is high, so groupthink and algorithmic recommendation makes more of a difference

On Facebook, where engagement is extremely high, and trust factor is high (family & friends), disinformation is a problem due to reinforcing spirals based on contents of a message

On Twitter, where engagement on average is miniscule, and trust factor is low, disinformation spreads faster but dies down faster too, so there will be trolls but not necessarily much conviction building

Therefore one of the lessons being that if the size of the network is externally determined by other factors, and people's propensity to consume is also similarly external, then the only variable that can be affected is speed of spread. And what this means is unambiguous.

We need circuit breakers on the internet.

II

If social media is effectively an accelerant of all sorts of information that falls on its unwitting users, how do we ever persuade anyone of anything?

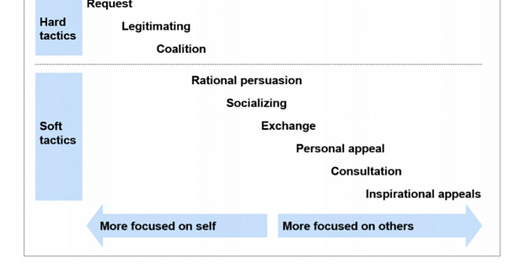

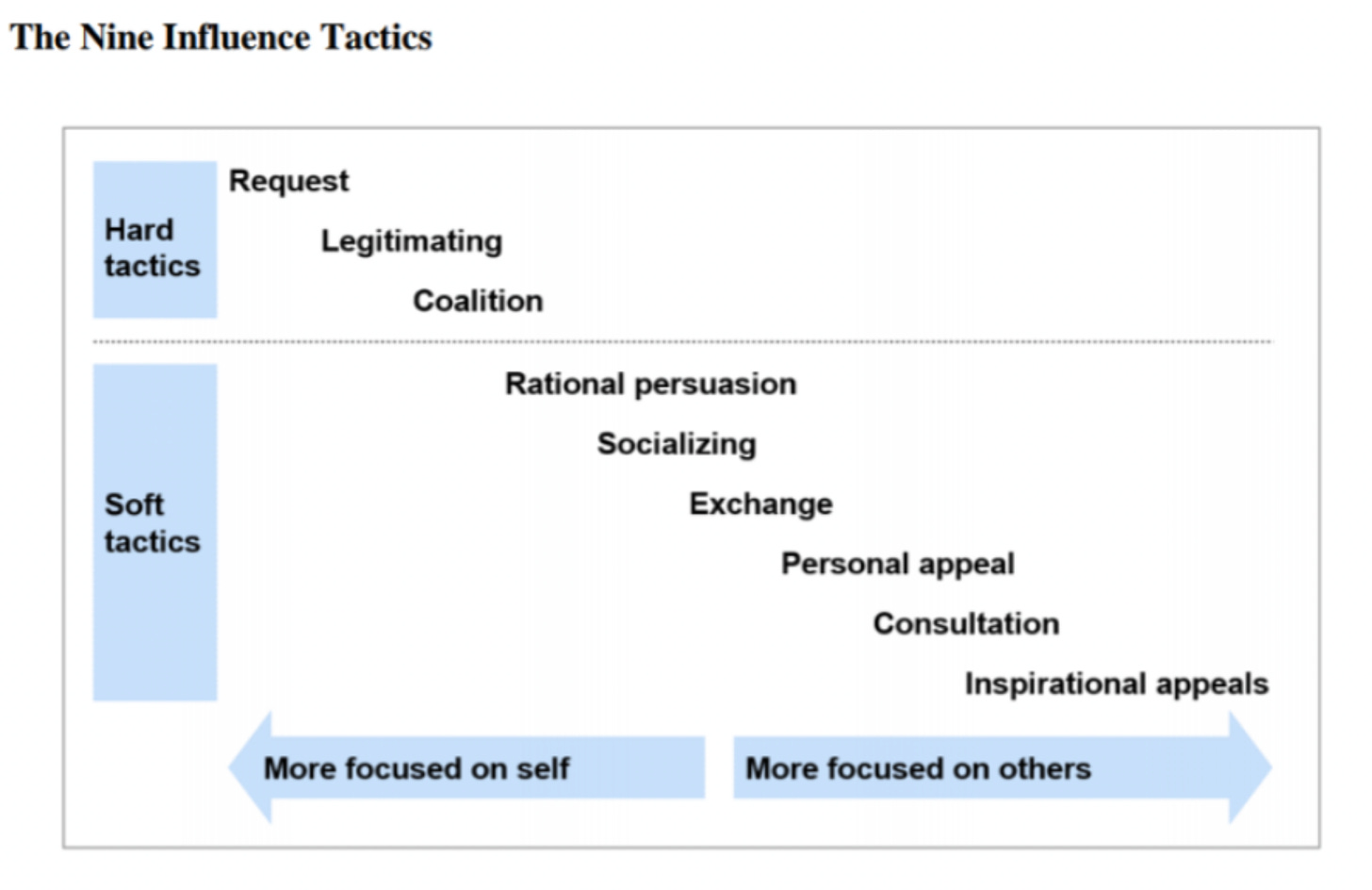

In management consulting there is a distillation of the types of strategies you could use to convince someone of something. At McKinsey it was called the "Nine Influence Tactics" and it was taught during the orientation and introduction to the firm. It's one of those clichés that turns out to actually work.

When we speak of persuasion. it's not just about the various modes of information transmission, it's also about the ways in which people actually take in and use that information. The hardest thing in consulting is rarely to try and solve a problem. In fact this is one of those things that only slowly becomes clear to you over time. In the business world there are often quite a few right answers. But you can only do one of them, and the entire difference between success and failure can come from your ability to convince someone else of your idea.

Which is where the extremely comprehensive looking tactics sheet comes in.

Like most consulting documents, does this have anything really new? No, not at all. Does it have anything you didn't know of before? Unlikely too. But in putting all of them together in one page can you try and systematically look at the factors and see if you've done them all?

Maybe let's have a glance at the political situation that the US finds itself in, where half the country (at least) doesn't trust the other half (at least). And a system with no trust will break itself apart. Our norms are what hold us together.

A big issue with most persuasion efforts is often that there are often invisible counterparties that the persuasion actually is meant to work on. In business negotiations you're not just trying to convince the person across the table, but also their customers, competitors, potential funders and the general market. In politics, you're not negotiating with just the politician across the table, but their entire party, multiple sub coalitions, and the voters themselves through the media. In science, there's clearly an incentive to convince other scientists of your findings, a fairly rigorous process, but there's also others they're convincing including the public and the science media.

In politics, since it's top of mind for most of the world and a clear candidate for extreme polarisation, persuasion seems like a lost cause. There even seems to be teams written about what drives victory in elections, persuasion vs activation. Part of the original sin is the moral superiority they feel and express towards the rest. Even if it is earned in many cases, it only makes the others harden. Nobody ever listens to someone laughing at them and decides to change teams. Instead they dig in. And it's understandable. Nobody likes being looked down on.

So what can we do, if we were to look at the options and try to apply them, what do we find:

Request: Ask the parties to play nicely together. It feels like this has been done in the past, to little avail, and still needs to be done more!

Legitimating: Make the sides of an argument lawful. This has been done by all sides each trying to referee the game rather than win by established rules. It's also a way that only works if all parties can agree on who's doing the legitimating, not an easy problem!

Coalition: Reach across party lines, help find like-minded people who have different and disparate interests, help make people multi-issue voters! Extremely unused for anything that gets too much press, since it can be made into an argument against you!

Rational persuasion: Works better when rational strategies are what both sides want. Definitely works at the voter level though not at the meta game at politician level, since convincing someone else that you did the right thing is easier than actually working.

Socializing: Try get better acquainted as people, and build a rapport. Among the least used things today it feels like, even as it's a throwback to the good ol' days of boozy Senators.

Exchange: Also known as horse trading in there biz. If anything it's way too overused and makes things too transactional. It's also a bluffing game, and a zero sum one at that, since you're just trading what exists rather than building anything together.

Personal appeal: Appealing to one's personal qualities seems surprisingly absent in political arena, only to rise up usually when you have some personal interaction with the topic at hand. Like how Cheney understood gay marriage better as a topic because of his daughter. This is clearly not a reliable strategy by any means.

Consultation: Committees, think tanks, reports, debates, surveys, panels. So many ways to consult everyone and try to create a consensus opinion. Also the biggest source of gridlock as oftentimes getting to a common denominator of an opinion isn't possible without significant wastage, especially as people game theorise their way into asking for more rather than doing a good faith discussion.

Inspirational appeals: Yes we can!

When you look at what people actually use in the business world, you see that most people end up using Rational persuasion. This makes sense if you believe business folks are rational. You explain logically what the best outcomes need to be, and then follow through. But even within the world of business and money this doesn't seem to be enough most times, much less in the world of slightly less tangible metrics, like politics.

And no matter how you move back and forth amongst these options, it's difficult to play a game and a meta game together at the same time. After all there are only three ways to succeed in any argument:

You succeed in the argument by one of the above methods

You change the game's rules, i.e., you choose different definitions of success

You play a different game altogether!

Among the ways in which the information economy now has shifted is that options 2 and 3 have risen in prominence. It's easier to change the rules through the courts, or play a metagame of loyalty to ideology, than to actually focus on playing the game.

III

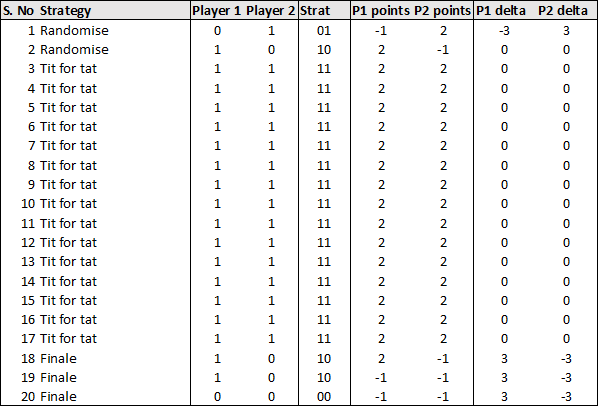

My first team building exercise in business school was an iterated prisoner's dilemma. I'm still not clear what it was teaching us to do frankly, since there was limited theory imparted to us. What I do remember is that my group won the game though mostly by playing unfair. It was a game played over 8 games sequentially. We played tit for tat for the first 6, and when the rhythm of both parties playing "cooperate cooperate" had gotten established, we played defect. Once to gain the point and once more because the other team was playing tit for tat by then too.

Several years later I realised that tit for tat was a stable strategy within iterated prisoner's dilemma games and emerged pretty naturally if you simulate enough of them. The large majority of good strategies end up somewhere in that vicinity!

But the thought that stayed with me was that once you know the game is coming to an end, the advantages of playing Defect as a strategy skyrockets.

When you look at how the strategies could affect a potential change as the turns come to an end, it's that whenever there is a higher premium to Defect, or a lower Defect punishment, then you can Defect several turns before everything ends.

Link to a worked spreadsheet for a stylised example - https://docs.google.com/spreadsheets/d/1mgi_4AYh0PJQ_Nzod1Tk7Ri2Ob8o1qKCJGBb8rZiEZk/edit?usp=sharing

So if you assume that one of the incentives to play a stable strategy is to ensure you never get your point total too negative through, let's say, the mechanism that anyone who gets a number too low gets eliminated, this means that you will do whatever is needed for continuation purposes for as long as that's a viable strategy, and then shift towards point maximisation once the end is visible.

IV

To summarise some strands:

Information transmission depends tremendously on the medium that carries the message, and the message style itself.

There are multiple methods of persuasion. They work well within smaller decision making groups, and work best when dealing with players who are aligned as to the rules of the game.

Playing any iterated game requires that the players treat the continuation of their right to play as a critical consideration to satisfy.

The counterpoint therefore is that depending on how the information actually moves around amongst the audience, and the meta games that exist, the strategies would have to shift widely. In a world where positioning becomes the most important component to ensure continuation of the right to play, success can't be determined by anything that can threaten that very continuation.

All strategies become less about success in that negotiation, but rather one of downside protection. Every action gets tainted by the potential for elimination.

So if we want to persuade others to a point of view, we have to:

Play the same game as they are. There's no point in using the tactics at your disposal if you're speaking to different constituents, or just have drastically different ideas of what success even is!

Try to minimise the downside of accepting a persuasive compromise, and

Make sure they're not worried about getting kicked off the iterated game they're playing.

Granted, this is less an action list than a framework, but without this we're all just screaming into the void and hoping someone hears. We can't shame someone onto changing their views. Neither can we browbeat them necessarily, not without making them annoyed at you for trying.

There will always be group effects and multiple constituencies and ideologues and different communication tactics. We can't complain our way out of reality, but deal with it in its complex messiness. And find a way to play the game even when everyone else is trying their damnedest to change the rules or play a metagame. Otherwise we're all just doomed to a life of talking past one another. That's not just a recipe for failure, it's also a much more boring place to live.