The Case Against Prediction

And for fast reaction

Sometimes I think how in markets there are investors and then there are traders. Investors take a view on how things will evolve and what the future will look like. Traders will take a view on the shortest timeframes and react swiftly seeing what’s changing in the markets. We need them to have a well functioning market. Not just them, but let’s talk about them here. And it feels part of a bigger trend, between our love for accurate prediction and sidelining the need for fast reaction.

Now, it’s almost trivially true that predicting things correctly is better than not predicting things correctly. Whether in life or business or love or markets or governmental policies or war, it’s better to predict things better than not. This is true, and it makes sense.

Also, we love predicting things. It’s fun, exhilarating, maybe even like gambling! I’ve succumbed to it too, here for instance trying to predict what 2050 would look like. It’s undeniably fun! Which perhaps also explains why its memetic fitness is high and it’s been around so long.

One problem with this is of course that the world is terribly complicated. Each of our actions spawn further decision points, and further actions to be taken down the road. The complexity grows very quickly, even if the decision you make is just a simple binary choice.

Even if you know exactly how things will branch and exactly how you should react in such a circumstance, the sheer number of options will get away from you very very quickly.

Which also means that no matter where you start, for any amount of effort you are willing to expend, the idea of what you will do in the future gets murky beyond a certain point.

This is the Point of Futility. This is the point at which the cost of prediction exceeds a set threshold.

In idealised circumstances we do this often. The best example might be chess, which is both bounded in terms of what can actually happen and effectively infinite in the number of combinations, to the extent that most chess board positions are effectively unique.

But those who play well solve this through extensive preparation (taking on the high cost of surfing the positions), focusing on particular lines, and extensive heuristics built up over time!

The best players will have heuristics based on familiar patterns they’ve seen over time, a sense of intuition of strength and weakness, which act as a way to make decisions in the face of overwhelming future complexity. Whether it’s a lazy evaluation or something more grandiose, success comes from reacting to the opponent, not just perfectly predicting their actions multiple lines hence.

And yet we love to try and predict events.

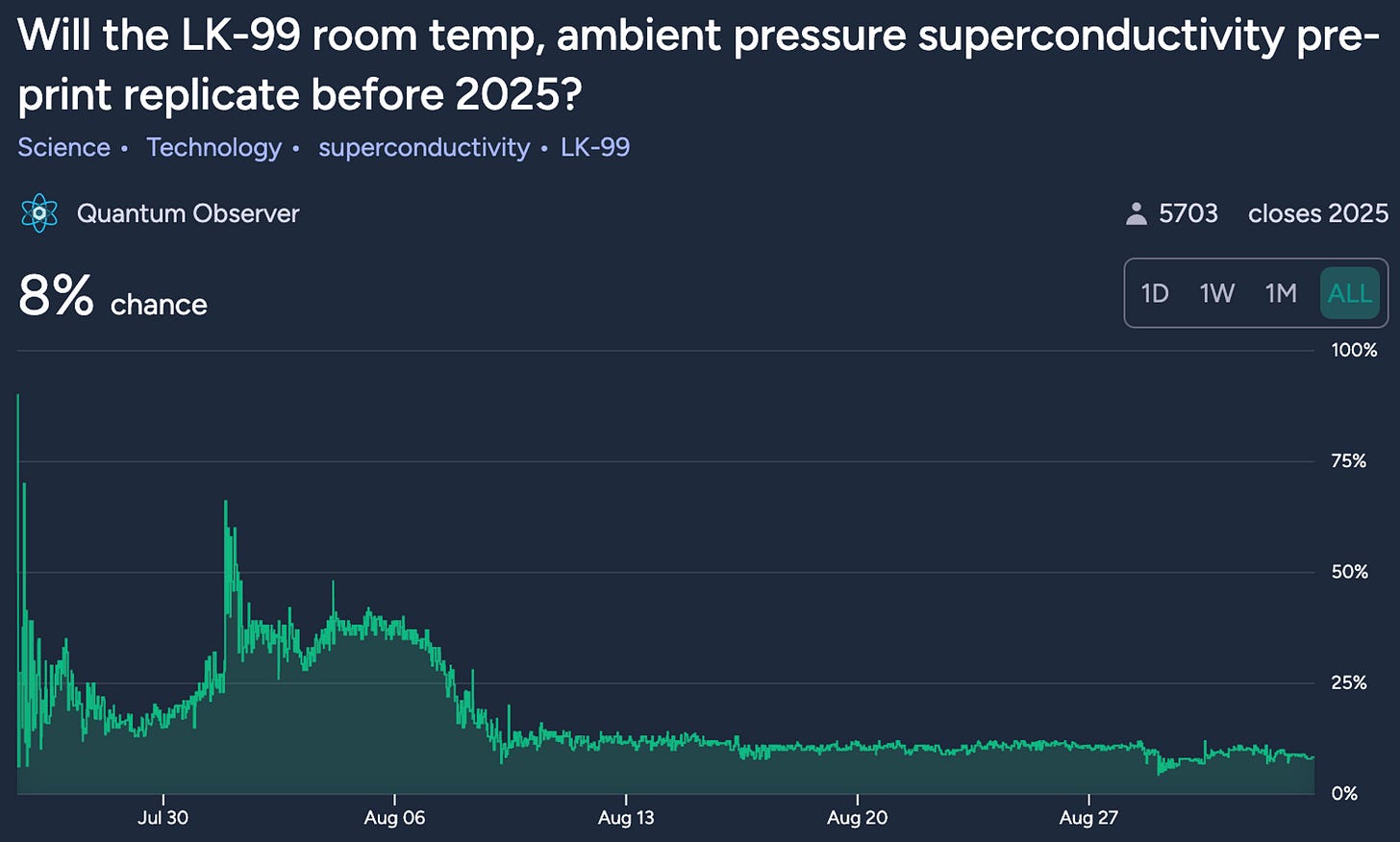

The recent breathless coverage of LK-99 is a good case in point, and perhaps the strongest signal where predicting things was considered useful.

They were breathlessly followed and used by both individual people on twitter and news reporters to try and explain something about what is likely to happen. It rose and fell with photos of people’s kitchen tables and blurred images of maybe-floating rocks.

And ultimately got destroyed by someone somewhere actually performing an experiment.

Was this a prediction market? Yes insofar as people predicted what they thought would happen and posted those. Then the actual resolution came from actual experimentation.

Prediction markets have been thought to be useful for quite a while, from business to science to politics. For instance, to focus their power on predicting something of interest there’s academic work on when we can trust its predictions.

It posits that prediction markets are particularly useful as forecasting tools where traders are constrained - legally, politically, professionally, or bureaucratically - from directly sharing the information that underlies their beliefs.

Though in analysing how extended real money prediction markets work to forecast the success of a new product, the evidence is not overwhelming.

Using real money prediction markets to forecast new product success improves traditional survey forecasts by reducing variability, but the markets do not provide a "crystal ball" equilibrium and only predict as well as the public signal provided by the HSX movie market game.

When you compare this to the fact that prediction markets aren’t really used in many places for anything useful, we’re left with the question, again. How useful are predictions actually?

An answer is that we do predictions anyway, so might as well make them explicit. But this ignores the biggest prediction market of them all, which is reality. Sure it makes sense to improve our predictions or make them explicit, but of course only if this is actually helpful to make decisions today so it doesn’t end up a vanity metric.

This is important. Because predictions happen across multiple timescales.

There are other methods beyond just markets that we use when we want to predict the future. For instance, the Delphi method is famous as a systematic process to help forecast events from panel opinions. It basically asks everyone their “blind” opinions, then presents everyone else’s points of view, and repeats it until (hopefully) consensus emerges.

Is this useful? Sure. Is this actually predictive? It’s unclear. For some things where you want the aggregate answer to be mediated by experts it seems likely, in cases where ceteris is somewhat paribus, but it has hard boundaries beyond which it doesn’t scale.

Knowing it is useful, sure, but once you get a bit of opinion for all topics where opinions aren’t the base reality it’s probably more useful to move a bit closer towards the need for setting up speedy reactions than even better prediction. The Point of Futility

The crux here is that an obsession with prediction implicitly overvalues a certain way of making decisions, and one that is inconsistent with how we actually take action. Think about a couple of areas where we might find it useful. Not just prediction markets, just the idea of prediction itself.

To identify which papers would successfully replicate. The idea of there being a market might be interesting, but the true test is simpler - to actually replicate the papers. We could bet on the outcomes of those experiments, but that’s not actually helpful beyond acting as a ranking for our collective beliefs. That’s not as useful when there’s ground truth!

To figure out which products to make inside a company? The markets might help, especially if you make them heterogenous enough and deep enough. And expert panels can sure help too in making sure you don’t make dumb mistakes. But can they actually predict which ones will be successful in a new field? Or are you essentially hoping that the pattern matching holds, while you empirically test things out?

To make decisions about which TV programs to run a pilot of, or create a season of if you’re Netflix. You need to sort of predict this in advance, like a novel, because you can’t really write it as people read. It’s a singular act.

The very act of pivoting a startup or constantly iterating a product after you build it though is a way of reducing the amount of prediction that’s needed, and instead choosing to react fast instead to new information that arrives.

Even financial markets, which includes the gold standards like the Treasury markets or the Nasdaq, are to be treated not a prediction machine, but rather a right-now-weighing machine. One that captures information as it comes and quickly incorporates it into the price.

In other words, it’s a reaction machine.

I think that’s a useful paradigm. Rather than force ourselves to come up with more and more ways to predict the future, which is inherently unknowable, we start learning about what’s going on and teach ourselves to move fast.

There is the belief that the reaction time itself could be enhanced through better prediction. Which also seems trivially true, though once again the cost of doing that enhanced prediction isn’t taken into account. In most real life settings, the question is one of what to do with the resources we have.

In government settings or in policy settings this is rarely seen. Like when we talk about the topic du jour, AI policy work, there’s a lot of focus on predicting the course of the future and to ensure the regulations or strictures we put will suffice. There’s far less on building up the abilities to react fast to changes in the environment.

It’s what the best traders do. It’s also what the best entrepreneurs do, and the best investors. And the best operators. Not to mention economists or politicians.

We saw this repeatedly in the recent past. With Covid, we had multiple prediction efforts fall flat on its face, while reacting fast to changing circumstances might have been far better. When preparing for technological changes, its the same. We have difficulty seeing what is much less predicting what is going to be.

When the skill to move fast is lacking we end up forcing ourselves to try and predict a future so we can respond well enough. With every bit of increasing fog that becomes harder and harder till we spend so much effort in prediction that its counterproductive. Call me crazy but isn’t that what the entire world of software estimation ends up being? Or construction estimation if you’re trying to fix up a house?

Both modes are important, but one seems to win out memetically again and again. It would be so much better if occasionally we could say “predicting that’s really hard. Let’s just go from here and we’ll pivot fast when we need to.” It’s sad that this seems to be seen as normal only in one valley in the whole wide world.

A couple of important edge cases here. One is reacting swiftly to extremely high cost situations. Like an apparent nuke launch or an apparent AI foom. Quickness of reaction would be demanded yet not very helpful for producing the best outcome. Predictive knowledge has far, far more value - in support of avoiding the need for reaction at all. And that is what sensible people are advocating.

Second case is that signal detection dominates in some reaction situations. Warming is an example where clear signals abound. E.g., the oceans have clearly heated up, methane is rising, species and populations disappearing, fire and flood, temperature records. But we are doing nothing. The quick reaction/fast money faction is ignoring the signal and using every defense mechanism in the book to prevent anyone (not just themselves) from meaningfully responding to it.

Yes! Lots of resonance with Kevin Kelly's Pro-Actionary Principle (via Max More): https://kk.org/thetechnium/the-pro-actiona/

Every viable proposal for AI alignment will need "better tools for anticipation, better tools for ceaseless monitoring and testing, better tools for determining and ranking risks, better tools for remediation of harm done, and better tools and techniques for redirecting technologies as they grow."