The Costs of Efficiency

Are governments really that inefficient, or do we just not know how to measure efficiency?

There's an adversarial collaboration to discuss this essay with Stephen Malina, as a companion reading to this one.

Don’t just stand there, undo something

Basically, for any complex [system] to be sustainable needs to have a balance between two factors: resilience and efficiency. These two factors can be calculated from the structure of the network that is involved in a complex system. A resilient, efficient system needs to be diverse and interconnected. On the other hand, diversity and interconnectivity decrease efficiency. Therefore, the key is an appropriate balance between efficiency and resilience.

I

In my last post I wrote about the pros and cons of a wealth tax. Since I wasn't vehemently against it, I got my knuckles rapped pretty nicely. The big question being: Should we trust the smarty pants who earned large sums of money decide what to do? And isn't the government just really inefficient at doing anything?

So I wanted to have a look at the question here, on whether the government does anything efficiently, and what efficiency means in the first place.

There are a large number of solutions that are regularly offered in politics, in business, in economics, where the argument runs something like this:

"If we do [Policy X], it would be beneficial"

"But we can't do it because it'll be highly inefficient"

"Why will it be inefficient?"

"Because it has always been inefficient"

"Well, this time we'll do it better"

And the cycle begins anew.

But surprisingly, there is a sparse literature that compares public and private sector efficiencies.

II

To start with, there's something that bugs me about most reporting around political programs. They never give you a decent cost-benefit analysis of what we're doing or why we're doing it.

For example, the US is trying to pass a monster bill to help folks who've been hit through the Covid crisis (if you're reading this several years later, substitute your own economic crisis here). And one of the arguments that pops up is whether we should universalise the benefits and just get it done, or whether we should make them means-tested so we're not giving benefits to those who don't need it.

No matter what you do, there are trade-offs. Universal programs (like social security) are cheaper to administer. They're cheaper to administer even when they're highly complicated, under-resourced and under tremendous pressure (see NHS).

This has been studied by economists in the past. Korpi and Palme in 1998 and Brady and Burroway in 2012 found that universal programs had a greater redistributive effect and were more effective than means-tested or targeted programs.

The argument therefore ends up becoming a philosophical debate about whether the undeserving getting benefits is a net bad (yes it is) vs having some slippage is worth the cost if we can speed up the delivery of said benefits (yes it is).

What I don't see much though is an empirical comparison. What % of eligible people will be left out if means-tested? What % of the spend will end up getting wasted as unneeded admin spend if we means-test? And why aren't these two numbers at the top of every single newspaper? There are individual assessments of this from the budget office, but little of it is in a coherent narrative.

So let's have a look.

The unseen problem of means testing social programs

First, some insight from Matt Yglesias who says:

TANF (temporary assistance for needy families) participation rate is 25%

Medicaid is 75-80%

SNAP is 84%

WIC (which provides supplemental nutrition to pregnant women and infants) is 51%

EITC is 78%

The burden we place on programs when we don't make them universal is this. Depending on the program, that's impossibly steep. That's the "false negative". It's the price we pay to ensure that we're being fair.

There was an interesting quote by a British Conservative MP on this very notion:

The estimated cost of adopting means testing for all benefits is not available and could be obtained only at disproportionate cost

Another response, to a suggestion that the richest households may be made exempt from receiving certain benefits necessitated this comment.

Since government does not know people's wealth it would require new and very substantial information collation and processing to implement that [policy]

What this suggests is that means-testing programs has a problem not just with slippage, where eligible recipients might not get the benefits, but also an increased administrative burden, the size of which is oftentimes unclear.

But let's have a look at a few other cases to see what we find.

Administering social security

Cost of administering social security benefits has come down as SS has decreased by a factor of 4 over the past 6 decades (the absolute figures have grown 30x), showing some gains in efficiency, at least until the 1990s. Data here.

Also for comparison, the TANF policy above has a cost of c.11% for it's administration, as a point of comparison.

Administering Medicare

Medicare's administrative burden is widely accepted to be around 3% of its costs vs 5-8x that for private insurance. But the counterargument here that says Medicare seems cheaper because the per patient cost is higher and they use outside agencies. All put together this paper finds that their costs are comparable, and maybe even 5-10% higher, than private counterparts. But that only goes to show my original point, which is that administering insurance seems to cost 15-20% of the premiums!

When administrative costs are compared on a per-person basis, the picture changes. In 2005, Medicare's administrative costs were $509 per primary beneficiary, compared to private-sector administrative costs of $453.

For comparison, NHS in the UK spends around 8% of its budget on management and administration, despite (or because of) having around 3.7% of its workforce in management. This data's around a decade old, but the trend doesn't seem to have shifted much (though there's an OECD report suggesting it's 2% now)! It's notable that this is half of what the US spends, even assuming that Medicare is inefficient too!

What about in the EU

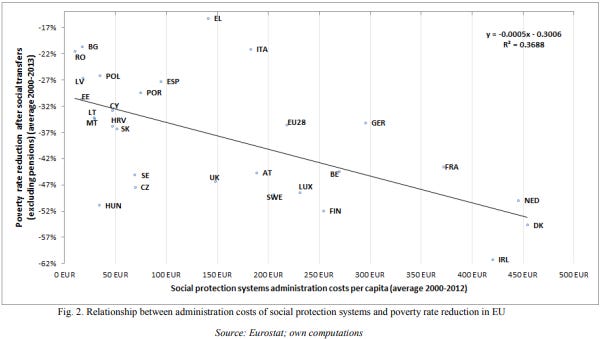

What if we looked at an overall relationship between admin costs and its actual stated purpose?

Turns out we find a slight inverse correlation, which is what we'd expect anyway. If things cost more to administer then we should expect to get less gains from it.

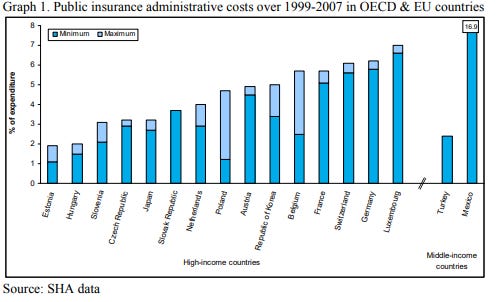

Health insurance admin cost variance

What if we looked at WHO's report on admin cost variance in health insurance schemes? There's a wide variation, based on how countries actually count this, but it can go from around 3-4% at the bottom to 6-7% at the top. The funny thing is that this data holds for the public schemes, especially for larger countries where you'd say that the benefits offered are sufficient. When measuring private schemes, the numbers go up 2x to 3x in most countries. For what it's worth, Germany means tests everything with typical German efficiency, and they sit comfortably near the top at around 6% for their admin costs.

I end with this prescription from a UNDP study comparing private with the public sector.

Healthcare

The comparative efficiency of public and private health provision is well studied.

Studies typically find either no significant difference between ownership models, or are inconclusive.

Within the private sector, evidence suggests that non-profit providers are more efficient than for profit providers. This may be explained by incentives to over-treat by private for-profit providers.

For instance, in an assessment of healthcare by the US Institute of Medicine:

30 cents of every medical dollar goes to unnecessary healthcare, deceitful paperwork, fraud and other waste. The $750 billion in annual waste is more than the Pentagon budget and more than enough to care for every American who lacks health insurance… Most of the waste came from unnecessary services ($210 billion annually), excess administrative costs ($190 billion) and inefficient delivery of care ($130 billion).

Education

Evidence from high-income countries is inconclusive

Evidence from low- and middle-income countries suggests private provision is more efficient than public provision

Private providers often have more recruitment autonomy, lower pay levels, and market-like conditions. These may contribute towards better efficiency

State services

There is conflicting evidence on the impact of ownership in the water, sanitation and waste sector(s); in some cases private ownership (or private participation) is associated with greater efficiency, and in other cases less efficiency

Geographic and other service delivery characteristics are more likely to determine efficiency than ownership

The conclusion seems to be that there is no particular magic in making the public sector less efficient.

For those unconvinced, this is also evidenced as seen here, here, here and here.

III

But it does seem that the public understanding of the situation seems to be that government is somehow uniquely horrible at getting anything done. Why could that be?

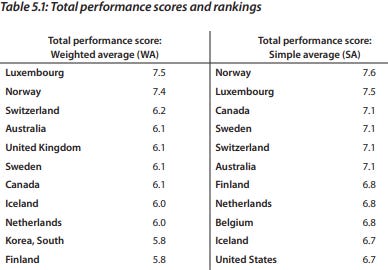

Looking at an analysis of government in the 21st century, measuring the performance of various governments against a balanced scorecard metric of 20 categories including Economic indicators, Health outcomes, Social outcomes and OECD Better Life Indicators.

And yet, here we have evidence that the United Kingdom is somehow better than Finland and Iceland? Granted, balanced scorecards suck, but it still shouldn't be this suggestive!

Also, the conclusion of the study states:

Looking at societal outcomes, a comparison of public sector spending variables and outcome indicators such as life expectancy, infant mortality, crime rates, and educational attainments shows that the relationships are complex. While there is indeed a positive association between government spending and favourable societal outcomes, much of this association is for lower amounts of spending with improvements leveling off as spending or public sector size rises above a certain level. For example, in the case of life expectancy at birth, an increase in the government expenditure to GDP ratio from 20 to 30 percent is associated with a gain of three years. However, growth from 30 to 50 percent yields only another year

Clearly there seems to be some form of a "Laffer curve" for government spending too, in terms of their overall efficiency.

Overall there are two ways by which economists look at efficiency.

Technical inefficiency, where you can't reduce any input without reducing the output

Allocative inefficiency, where inputs can't be substituted for one another without raising costs

With these, whether you're measuring input efficiency (minimisation of input) or output efficiency (maximisation of output), the theory is that you require competition and a thriving market for the demand and provision of services.

You can probably see the problem. If you have combined several inputs in some particular combinations to get some output, then you have to measure that output against something else. For instance you might compare policing success rates against a Platonic ideal of a previous era, plus some trendlines.

But those don't give you enough information to suggest if something is good enough or not.

So we end up measuring efficiency through inadequate variables like quasi outputs (wages per employee, graduations per education dollars etc.). But those are not the outputs we want. Those are themselves inputs to reach the final outputs, leaving us nowhere.

For instance, one of the arguments that's made is around the extraordinary inflation in the size and bloat of the government. Here's a look top down at government employee spend trends.

From 1952 to 1972, the cost of the public payroll multiplied more than fourfold, from $35 billion to $150 billion. The 330 per cent increase over that period exceeds the 247 per cent growth of employee compensation in private industries ($161 billion to $557 billion). In 1952, the average worker in private employment earned 5 per cent more than his counterpart in government. By 1972, he had fallen 10 per cent behind

Maybe they're doing way more important jobs, or maybe the private sector is getting unfairly screwed, both likely possibilities I suppose, but it's still weird.

But the trend of increased inputs for flat to declining per capita outputs is a hallmark of multiple government departments - Department of Agriculture, Defense, Postal Service, Education, IRS, and more.

What this tells us is that there's probably a productivity gap problem in the government. But it's still unclear if this is because of the cost disease (explored here) or organisational inertia (explored here).

But if this is the case shouldn't the government come out as hopelessly wasteful in the analyses as shown in the first part?

The best evidence that’s often cited is the fact that institutions that once were public, but are now privatised, become more efficient. The wave of privatisations during the late 20th century underscore was based on exactly this premise.

For instance:

There is significant evidence that privatisation can lead to improved efficiency but improvements in efficiency through privatisation is dependent on a number of additional factors. ... A study using a sample of 129 privatisations from 23 high-income countries, found significant increases in efficiency following privatisation (D’Souza, Megginson, & Nash, 2005).

But it's not all roses. Privatisation only works when there is substantial levels of capital market development, enough competition, and clear human capital with managerial incentives. At that point you're effectively saying that there's enough state capacity that's been built up so that the privatisation can succeed. For instance, private prisons, for example, are a pretty major stain on the enterprise. And also, in a beautiful case of irony detailed in this HBR study, the argument gets turned on its head:

Starr also attacks the claim that privatization leads to less government. He contends that profit-seeking private enterprises servicing public customers will find it in their interests to lobby for the expansion of public spending with no less vigor than did their public sector predecessors. In other words, privatization introduces a feedback effect in which influence on government now comes from the “enlarged class of private contractors and other providers dependent on public money.” This influence is especially dangerous if private companies skim off only the most lucrative services, leaving public institutions as service providers of last resort for the highest cost population or operations.

As I said, it still seems a mixed bag at best. If you live in San Francisco I'm not sure whether this would be an argument in favour of more or less of this.

IV

This is the fun speculative part of the essay, to try and figure out why it might be that we think the government is a complete wastrel.

One possibility is the spotlight effect. It is that the governments have highly public failures. When Solyndra goes bankrupt, it is on the front page of every newspaper for weeks on end. Politicians make entire careers shouting about how this is horrible. When private companies screw up, unless they're very unlucky, it gets buried pretty quickly.

Second possibility is the selection effect. Governments only do the annoying things that usually the private sector sucks at.

For instance, did you know that New York had multiple different private subway lines back in the day? That's what the colours denote in the lines. But they were late, with horrible operational efficiency, and had to be bailed out enough by the state that they were made public. And it runs still.

Also if you were living under a rock during February 2021 you might not have known that Texas has a crazy power outage and prices spiked enough that people had to pay $10k+ in electricity bills. And did you know that Texas has a separate grid that's effectively at least partially privatised?

So when the government takes up only the shitty tasks that the private sector sucks at, we shouldn't be surprised that they're pretty bad at doing them.

A third possibility is that government has just grown larger, because we now ask more of it. No longer constrained by the most minimalist needs as the society matures we ask more of our governing institutions. And it's not at all clear that this is prima facie a bad thing!

But looking at the trend here it does seem that there is a bit of truth to this theory. The spend trajectory seems to go up in accordance with per capita GDP, which is to say the richer country governments seem to spend more per citizen than the poorer countries.

Another thesis is that government is in literal charge if maintaining a vast and expansive nation. It's a thankless task, since it's only your failures that are visible. But it's their maintenance that enables our innovation.

Which means that the explanation is that the way we measure efficiency in private sectors are different to government. In the private sector world there's freedom to define your goals. In the government, the goals are often external. They have to serve the whole populace, not the fraction which are able to afford a service, or which is easily and cost effectively serviceable.

Which means that we're forced in the public realm to focus on universality of service provision, rather than the "efficient" provision of services to a fraction of the public.

V

And here we come to the conclusion. I'll admit it, I'm confused. I started this article to analyse why it seems like the government is so inefficient at so many things, but we need it anyway. But then the literature seems chock full of articles about why basically it doesn't matter as long as we have enough government-like services and government-like stability, in which case anything goes!

And yet who likes their government services? (well apart from of course Japan and Singapore and Nordics, but we all know they're weird…)

Most of the arguments on why government is inefficient seem like fait accompli. They provide services without the profit motive, so they're inefficient. Or they provide services with no competition, so they're inefficient. These seem almost axiomatic statements rather than empirical facts.

Even as revenue generating efforts, the government has some fantastic ROI options:

IRS - Each dollar invested in the IRS yields $4 in higher revenues, with even greater returns for spending on enforcement

Healthcare - The review showed that the median RoI of public health interventions across 52 studies was 14.3:1. (Note, not all £14 here are just savings)

Primary education - Research shows that for every dollar invested in high-quality early childhood education, society gains up to $7.30 in economic returns over the long-term.

Basic research - Economists suggest 20% return on public investment for research and innovation

Considering the ROI calculations alone, surely we should give the government even more money. Why isn't this the most widely debated part of governmental fiscal policy?

I mean sure, most of the military spending seems kind of a dead weight, but it's still decent GDP fodder if a DARPA effort and GPS comes out of it. Right?

As I said, I remain confused. It feels like government is a pinata we love to beat on with powerful hatred, though it keeps dropping candies all over the place. If anyone has good empirical research here I'd love to read it!

Rest assured, this hasn't been a long aside just to push a universalist approach for everything, or indeed a universal basic income (though I think that might be a good idea).

The benefit of efficiency has been higher equality through better predictability and lower slippage. The cost of efficiency has been baroque bureaucracy and impenetrable complexity. By making things more interconnected and complex to understand we make them work for us. We've sacrificed metis for efficiency. But it seems an unavoidable tradeoff.

We can still conclude that there are things we should take off of the government’s plate, because the private sphere has gotten good enough and the regulatory sphere has gotten mature enough that they can handle it. Banks are an obvious example. Coming from India as I do, which has a history (and present) of extremely strong state banks, this trend was something I saw happening as I grew up.

But this doesn’t necessarily support the inefficiency narrative still. It supports the narrative that markets need to evolve slowly. And applying that argument to large mature developed economies seems to create rather perverse outcomes.

And if anyone still feels like we should have less government because they’re terribly inefficient, I’d love to know why they think that too. If it’s just the paraphrased anecdotal argument about DMV sucking, I’ll just say that a) the last time I went the DMV was pretty good, and b) god forbid you have to deal with Oracle!

I feel like you have overlooked a massive reason why people perceive the government as hopelessly inefficient - because of a massive, decades-long PR campaign pushed by wealthy individuals, big companies, and the Republican Party to convince large amounts of people that the government can’t do anything right. Look at all of the advertising, education and “think tanks” funded by the Koch brothers and the many politicians who have complained about “welfare queens”, and Ronald Reagan’s entire campaign. One of his most quoted speech lines is: “The nine most terrifying words in the English language are: I'm from the Government, and I'm here to help.” I can point out more examples if you like but if you look around just a bit you will see they are everywhere. The Republican Party has made increased privatization and criticism of “wasteful” government spending a central talking point and has pushed this message hard through its media arms.

The fact that a lot of people think government is hopelessly inefficient doesn’t mean there has to be some hidden strong evidence that everything the government turns to garbage. It could just be that they have been propagandized into believing something that doesn’t have good evidentiary support. At one point in history the vast majority of people believed in polytheistic religions but that doesn’t mean there must be gods and goddesses running around someplace.

I’m sure you don’t want to come off as being politically partisan. But I’m not sure you can understand why the perception of vast government inefficiency exists without examining the powerful people and corporations that benefit from that perception and invest lots of resources to prop it up.

I think the simplest reason Govt is considered inefficient is because it is hopelessly inefficient. I fear you are getting lost in statistics, papers and coming to wrong conclusions. This is why I find it helpful to always think deductively to ground my inductive reasoning. Consider the following questions :

Is firing an employee who does not work a good for the organization or not?

Is providing monetary incentives to customer satisfaction good for an organization or not?

Is it better to delegate responsibilities to employees to meet targets or better to define and keep writing sets of rules to reach targets?

Which strategy attracts and keeps young talent, high pay, high rsponsibility and high growth potential (and higher risk) or long term stability, low risk, low growth and mediocre pay? For each of these questions, the private sector does one thing while the government employs the opposite strategy. Which would be more efficient?

If the government in spite of employing the clearly bad strategy keeps getting efficient results, then our priors have to be wrong and the private industry clearly has a lot to learn but I reckon that is not the case. It's much more likely that the government is just as inefficient as it's predicted, and you're just getting lost in statistics. You can easily come up with 6-7 other such organisational deductive questions, where the government clearly uses the wrong strategy. The only times the Government is successful is when it has programs that follow at least some of the above questions (especially the 4th one, which matters more) as in the case of DARPA or early NASA or when it gives money to the private industry which can cause issues like Solyndra but also successes like SpaceX, Tesla, Internet etc. My favourite story of Government Programs done right is the Apollo Moon Mission 1969 (written in a book by Charles Murray)