I. The future is an abyss we can’t stop staring at

Once you start thinking about growth, it's hard think about anything else. That's what Robert Lucas, the famous economist, said. I think this is equally true about the future.

Predicting the future is the single most exhilarating activity that anyone can take. In jobs and in life we try to figure out what the world is likely to be. If you’re in the financial world this is mostly the actual job. But even elsewhere, whether you’re building a company or figuring out what or how to teach your kids, a view of what the future is likely to be is inevitably part of the decision.

There seem to be two ways to predict the future. One is to look backwards at our history, and try extrapolate from what has happened. One’s to think through what we want to have happen, imagine it in better detail. We find ourselves routinely stuck between the unknowability of the future and the necessity to take action.

In the old days, we used to have Oracles whom we could ask for guidance. They were present all over the ancient civilisations, the Greek, Roman and Egyptian empires. Delphi in Greece was believed to be the center of the world and the home of the god Apollo. People would travel from all over to seek the counsel of the Pythia, the priestess who acted as the voice of the gods. She’s supposed to have predicted the fall of Troy and the fate of the Trojan War, including King Agamemnon’s sacrifice of his daughter Iphigenia.

The Roman senate, an august and not particularly sentimental body, consulted the prophecies by the Roman oracle written down in the Sibylline Books. It is meant to have predicted the rise and fall of the Roman empire. The Egyptians had an oracle of the dead who too had the power to predict the future and communicate with the deceased. Whether it’s indigenous tribes like the Lakota communing with the spirits to get guidance, or the Yamabushi in Japan consulting the divine, the urge to get guidance in regards to the unknown void of the future lies very deep within us.

Indeed, it would seem the efforts to control our conceptions of the future have been around for as long as mankind has been around. You don’t quite need to be Nostradamus. Our ability to dream is what makes us human.

But we don’t have these spirit guides anymore. The studied insights from those who could read and write, the scribes and the priests, is now available to everyone. The insights of the experts are subject to peer review, but we’re all peers. There still are those who consult the stars for their children’s future or to assess the suitability of those they would marry, but its pro forma, done for ritual with the meaning having been leeched out of it. And so we imbue the future with meaning and chart our paths, like celestial navigators of time.

In the modern world, without the benfit of a divine authority, we’re stuck needing to figure out the complexities of the world ourselves. We ask experts and conduct polls and look at the markets, all to try and understand what the future holds.

II. Prediction failures surround us

Tim Urban’s view of how we look at our past versus how we look at our future gives a great view of life as seen from the inside. The branches, at any point, are invisible, and make it even harder to figure out how to choose what to do. And so we try and resort to better ways of measurement, to reduce errors. Prediction markets. Expert judgements.

Experts were the original answer, even as they moved from divine authority to intelligence and studied knowledge. We used to be able to rely on their judgements. But that time has gone. Now that we live inside a communal panopticon, we see their type 1 and type 2 errors in front of us again and again.

We try markets, which work quite well when we can ascribe a clear metric and take actions to affect it. But markets still need an enormous amount of background effort to make it work. We have regulation with the likes of the SEC that aims to protect investors and enforce transparency. We have a decentralised market structure with multiple exchanges and market makers and audits. And a truly gargantuan media and discovery sector to ensure information flows freely!

And despite all the efforts we still had major failures like the housing crash of ‘08, most of what seems to have happened in the 2020-21 era, the LTCM debacle, and so many more! And it’s not just in the financial markets either, we’ve seen the same issue play out in real estate Ultima Online and Final Fantasy, not to mention a self imposed economic collapse in EVE online! Even in the fake markets we set up for play we see the same dynamics, a ghost of Goodhart’s law and general greed creating powerful distortions.

Not to mention all the times when markets just fail to work: externalities whose costs aren’t reflected in the market price like pollution, public goods which are non-excludable or non-rival, monopolies, or just the lemons issue from information asymmetry.

But somehow the future, while unknowable, feels something that can be studied and managed if we have the right tools. That conceit is deeply ingrained in us. We have access to more information and tools than ever before, new methods of forecasting. From using machines to learn and identify patterns from past events we keep trying to make the ineffable a bit more effable.

III. Pre-paradigmatic worlds demand experimentation

The way we used to do it, the way of the Oracles and the soothsayers shorn a tiny bit of magick, was to try wide eyed empiricism. Try something, and see if it works. Theory says your body has 4 humours, and this plant will reduce the one that’s inflamed. It’s not true, but turns out empirically it works.

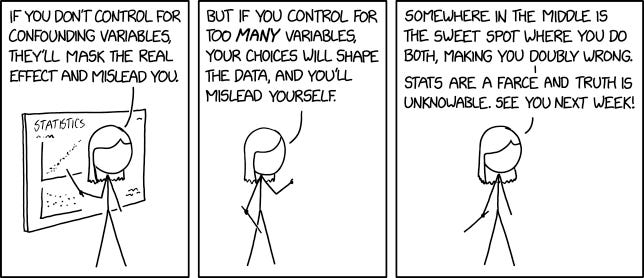

In the modern era, as we understood that predicting the future requires understanding the present, we built cathedrals to truth. We started doing randomised trials with double blind and control groups, and tried to figure out the link between cause and effect through natural experiments and statistical sophistry.

And in doing so, we somehow forgot the idea of doing experiments as a way to figure things out. Experiments became sacred, something to be performed carefully and restrictively lest you conclude something wrong.

In their smart book review about historical scientist and modern medicine’s whipping boy Galen, smtm writes:

..whatever Galen might have been lacking, it certainly was not the empirical bent. He was no armchair philosopher, and was more than happy to cut up lots of animals to make a point about the function of the ureters.

This is funny because, again, this is the opposite of the story we’re told about Galen. He’s described as a pre-scientific or even unscientific thinker, believing that experimentation and investigation are a waste of time. Clearly this isn’t the case, and he made full use of all the resources available to him. … Galen starts looking more and more like a lone light of empiricism in the wilderness.

The method that he followed, a couple millennia before the enlightenment, seems to be to hypothesise about something, do some empirical research, and from his observations to create a new theory or to confirm one of his hypotheses.

Remind me, what does this look like?

Oh that’s right.

This blog does tend to sit amidst the worlds of science with its sense of method and reliance on empirical validity and a relentless focus on falsification, and the world of business which relies on feelings and experimental gut instincts and an unreasonable reliance on wagering on possibilities of success. The pre-modern scientific era seems awfully close to a pre-paradigmatic view of what the rest of the world is as yet today, a seething mass of n=1 experiments and wild extrapolations and beautiful storytelling.

We could blame the rest of the world for not living up to the rigorous epistemic standards of scientific method and reasoning, or we could joyously embrace the world for giving us the chaotic standard against which Seeing Like A State beat its rational forehead. The art of trying things out and seeing if it works, whether that’s growing mold in a petri dish, or putting shinier rocks in a watch, or figuring out what the people in the future might demand to place your investing bets.

When Oracles are gone and experts turn unreliable and large scale market studies are often unreliable for specific problems, one way out is to run experiments. And it works, most of the world runs on these “unscientific” experiments.

And it’s criminally underused.

The thing that the pre-paradigmatic world of business teaches us, that which science used to teach us, is that results aren’t purely the result of careful, painstaking, rigorous, peer-reviewed process following. They, like much else in the complex system we live inside, are chaotic, unpredictable and can only be reached through experiments and leaps of faith.

IV. The Demandscape is what we strive to find

If we plot out what we all want, created a map of our collective desires so to speak, we could create a “demandscape”; an egregore we collectively create and collectively try to satisfy. Whether you see the world as pregnant with possibilities that you should bring forth as an entrepreneur, or whether you see the world as a game to be played to win, understanding the demandscape is the best first step.

Without this, the confusion that exists on competing visions of the future are little more than battles about which particular form of the “demandscape” is real, and which is fictional. Sure, past can be our guide. Thuogh this runs the risk of over extrapolating, and assuming we would want faster horses. We could look at the invariants. Like Jeff Bezos said, the things we can say about the future are that people will continue to want things faster and cheaper. Though as is often the case it’s not particularly actionable.

We could look at the varying ways that technology is evolving or society is changing, and try and combine them to get a vision of how the demandscape would change. Like the idea that if we were able to work from home enough, a sufficient contingent of people would choose to want this. Here too you should be wary of assuming the inevitable conclusions, since there will be unknown unknowns and just plain errors in your logic.

We all want to see the ways in which the future resembles the past, or the ways in which it will be different. Either are compelling. Both are useful. One of the better metaphors I’ve heard is treating this as crumblinology - like reading the future from entrails, just slightly more sophisticated.

In ancient Greece, you could get away with having a barely informed view of what the future held, with vague allusions, partly because the number of options of what could happen were fairly limited. Even in the past century in most of the developed and developing world, the probability that we could somewhat predict the course of our actions seemed a safe bet. Not in the sense that you could predict the future well, but the cost of not predicting the wrong future seemed low.

We should talk to others including experts, but can’t rely on their augury. We should look at the markets and price signals, but can’t rely on them as Mr. Market is so often either experiencing mood swings. We should collect data and analyse it to create our own fundamental beliefs, even as we’re all biased.

The reason experiments work in a system that’s not easily analysable is that they tend to be direct salvos to test the demandscape, to see if results follow action.

It applies to everyone. Scientists have to choose what to work on and which problems are both important and tractable to them. Entrepreneurs choose an idea and try pivot around it until it fits well into the demandscape ecosystem. Business is the effort of satisfying the demandscape, using whatever tools are available. Venture investors try and fund things which they think will become inevitable aspects of our existence in the future, once again trying to align with the future demandscape, and making a bet on the technological leaps required to get there. Markets try to distribute resources by each participant betting their vision of the demandscape evolution from the current point will win out!

V. Consilience

The lessons in thinking about the future are also all too often simple, if almost impossible to follow. Which is also why they still hold up. Look for long lasting patterns, protect your downside, think of actions as bets, don’t be overly trustful of either history or the data, and know that economic facts are social facts. There, that’s almost everything you need to know about life in one sentence.

The guideposts to the future are the collective wants of those in the future, the demandscape, and the tools which we have to satisfy them. Our dreams and designs combine them, sometimes untethered by the tools in our fiction, sometimes overly tethered to the tools and without imagination in much of our nonfiction.

We use the language of science to talk about our beliefs in the future - probabilities of predictions, proven assertions, but this is play acting. Much of the world and our knowledge remains pre-paradigmatic, and without much hope of finding a strong enough predictive paradigm either. There is no equation, maybe a wisp of hope of a statistical one a la Asimov’s Foundation. Experts are less wrong than Oracles, and markets are often more right than experts. There are gradations of accuracy as we spend more effort. But it’s not enough.

I’ve written about the need for a cone of foresight, of there being a limit to how much we can understand. There’s also the fact that participating in the investing world means we’re always bringing our ideas on what we believe into the decision. The natural conclusion might be nihilism, a sort of existential understanding that maybe we can’t predict the future after all.

That too would be mistaken.

When Turgenev first brought nihilism to the limelight, having rejected much of what we thought we needed like objective truth, morality and meaning, it was called akin to jumping into an abyss. Because without some referents what’s the point! Fortune telling and predictions are much the same, giving in to a belief that nothing can be predicted is as wrong as believing anything can be predicted.

Even as we are still in thrall of longer term research institutions, which lay claim to 10,000 year old clocks and focus on finding centuries old research institutions, the future’s becoming even less predictable. If you had tried to make a future-proofed house a couple decades ago, you might have put in ethernet cables and copper wires, maybe even a television antennae. But it would’ve gotten obsolete in record time.

Instead, Stewart Brand has talked about buildings that learn. To turn the unknowability of what’s likely to happen in the future into a philosophy of life. In manufacturing we talk about Just-In-Time methods. A way of getting things ony as you need them, not before to store. This is similar, a JIT form of consumerism. One that turns the fact that what you buy will get obsolete into a virtue.

It’s also partly an explanation of why the Colosseum was built to last 2000 years, while the modern skyscrapers are built to last a hundred or two.

The consilience between the need to know what comes next and the inability to clearly define what comes next is to focus on a just in time method for your decisions. It’s easier in some ways of life than others. It’s sort of antithetical to five year plans and elaborate schemes. It’s a function of knowing what you have and what you need, the skillset and the demandscape, and to build towards that every step along the way.

Running experiments is how the non-scientific world, which is most of the world, manages to function. Product managers at tech companies do this to figure out what they ought to do. Investors test strategies and make bets even though the strategies wouldn't pass the rigor needed of a sophomore chemist. Entrepreneurs test their hypotheses against their customers’ demandscape. Poets test their verses against the emotions it elicits in their listeners. None of these are rigorous, all of these are useful.

Most of the time, we look to the world of science to tell us how we ought to conduct ourselves in other walks of life. But the idea of unabashed experimentation is now only left in these corners. And it shouldn’t be so.

Experiments are humanity’s secret weapon. It shouldn’t be suborned by elaborate rituals and the need for robes. It’s for each of us to design and do ourselves. Marie Curie got radiation poisoning from her experiments, and Robert Paine discovered keystone species by moving starfish around. Surely those scientists need us to pay homage to them too!

Yes to more experiments!! In case of interest, I wrote something similar this week framed as “Treasure Hunting” - also quoting Stewart Brand’s How Building Learn :) https://mysticalsilicon.substack.com/p/treasure-hunting

Love this! Experiment boldly.

I think it's also important to delineate exactly *what* about the future that's important to know. If you knew 20 years ago that the Washington football team was going to change its name in 2022, would that really be beneficial? (Ignoring "I could make a bet they wouldn't" scenarios.) Even knowing that a technology will exist ahead of time is of limited value, since you can't actually use its features yet, and the devil is often in the details of features. (If you told someone in 2005 that the iPhone would exist in 5 years, they might very well prepare for use cases that it couldn't actually support.)

Cal Newport writes about this, saying that many people when planning for the future dream about the size of their bank account but don't get sufficiently specific about the *lifestyle* they want. The exact amount of money you own is far less relevant to your future happiness than whether you're living near the things that bring you peace and joy.