This suggested that France should replace the monarchy with an "economical royal automaton". This "mechanical king" could perform ceremonial functions, and his behaviour could be adjusted to accord with the changes in these functions. He could converse with visiting monarchs and could fulfil his other duties - all at a minimum of cost to the country. He could automatically sanction all decrees passed by the legislature and automatically appoint ministers in line with the wishes of the assembly.

Condorcet's parable in 1790, referenced in Dr Strangelove's Game: A Brief History of Economic Genius

[epistemic status: thoughtful]

The monarchy is an ancient relic by now in most countries. If you are, like me, sitting in the UK we have a beloved royal family whose ostensible purpose is unclear, but whose practical purpose is as a sort of well meaning figurehead. But one thing that the supporters and detractors alike agree on is that they are basically useless. If someone replaced them with an automaton, I'm not sure anyone will notice.

What's hilarious is that this is exactly what Condorcet said too. In 1790. How the times have changed!

But funnily enough the world seems filled with mechanical kings. Highly paid professions which are effectively people acting like automatons, with seemingly little of that which makes people seem human and well rounded. Is this why we're so dissatisfied? Because we're being made into automatons?

You can see this across most aspects of work. Especially white collar work, which was traditionally seen as the exemplar to aspire to. For instance, from the outside, lawyers and accountants seem like especially egregious examples of professions where the better you are, the more you seem to act like a smarter GPT. This is not to say there is no creativity involved, or humanity, or judgement, or other attributes. Just that the success in that profession seems to be determined by how much you are able to act like a machine.

Just as coders try and convert the messy human requirements into a precise logical language to interface with machines, lawyers try and convert the messy human requirements into a precise logical language to interface with the legal superorganism. Similarly accountants try and convert the messy human requirements into a precise logical quantitative language to interface with the broader regulatory superorganism.

When Graeber wrote about bullshit jobs, he suggested that some part of the reason we call certain jobs bullshit is because we don't see the value in what we do. And that can be because there is no value, or because we're one tiny cog in a giant wheel and to grok the wheel is an impossible task for most folks.

He blamed the rise of the administrative sector, within jobs and as its own industry, where people do mechanical things for no reason. But I think it extends further, to the increasing hunt for efficiency even in that administrative sector making a large number of jobs basically paper-pushers. Where you are given rules and strictures to adhere to, and your will and thought and initiative is strictly verboten.

I wonder if the box tickers and taskmasters that Graeber wrote about haven't infiltrated our other jobs, so that instead of remaining a separate class a la Omelas, they've taken up a percentage of what other jobs do on a daily basis. Whether its doctors or lawyers, everyone's at least a partial box-ticker today.

Sticking with those two, at least you earn a lot. Which should help, right? So ... are they happy?

As it turns out, accountants rate their career happiness 2.6 out of 5 stars which puts them in the bottom 6% of careers.

It's the exact same rating for lawyers by the way, 2.6/5. Doesn't bode well. One of the articles analysing job satisfaction for lawyers starts quoting as follows.

Sweeping changes in the way law is practiced, along with substantial changes in the environment in which lawyers operate have given rise to well documented increases in job dissatisfaction among attorneys.

We examined every major study of lawyers’ job satisfaction appearing in social science journals, law reviews, and bar journals. What emerged was not a pretty picture—what we termed high paid misery.

The article throws up a mystery that a large percentage of lawyers say they're satisfied, but contrast that with lawyers in private practice (less satisfied), in big firms (less satisfied) and more junior lawyers (also less satisfied). Which seems to be a problem.

Its in fact so bad for lawyers that there is an entire aspect of the recruitment industry that's specialised in helping lawyers quit. As a lawyer's blog notes.

What I didn’t realize was that the plight of burnt-out attorneys, particularly those at law firms, has recently spawned an industry of experts devoted to helping lawyers leave law. Attorneys now have their choice of specialized career counselors, blogs, books, and websites offering comfort and guidance to wannabe ex-Esqs.

The cause for this is the prevalent feeling that what they're doing doesn't matter. That they're just human versions of algorithms.

Our broader job satisfaction is often tied to a feeling of achievement, of progress, of not just being a cog in a giant Rube Goldberg machine. That's what makes work seem less like mechanical kings for most of us.

But an increasing number of jobs do make us feel like cogs, like a smarter version of GPT-3 where you're thrown some data to work out, where you're part of an assembly line. A smart and crucial part to be sure, but one where your contributions are connected to those of several others, all coming together in a Sankey diagram towards an end by which your individual contribution has disappeared. Where your work is as a tributary to a river that eventually empties into an ocean.

Condorcet's mechanical king is at the one extreme of this phenomenon, where the job the human does is so circumscribed as to essentially not require the human at all. It is the ultimate alienation; a machine could perform the job or close enough to it.

There is also a theory that once we eliminate the drudgery within our jobs we'll only do the smart, intellectually stimulating, stuff. I personally feel this belies the process by which we actually come to such creativity, but even if you didn't buy that, it pushes the creativity inherent in some jobs to an assembly line procedure, devoid of situatedness or personality, which kind of mirrors the complaints we see today?

Some of this is alienation as friendly bearded Karl wrote about, just applied to cognitive instead of physical labour. The meaninglessness of one's job comes at least partly from the feeling that what you're doing is irrelevant or unnecessary.

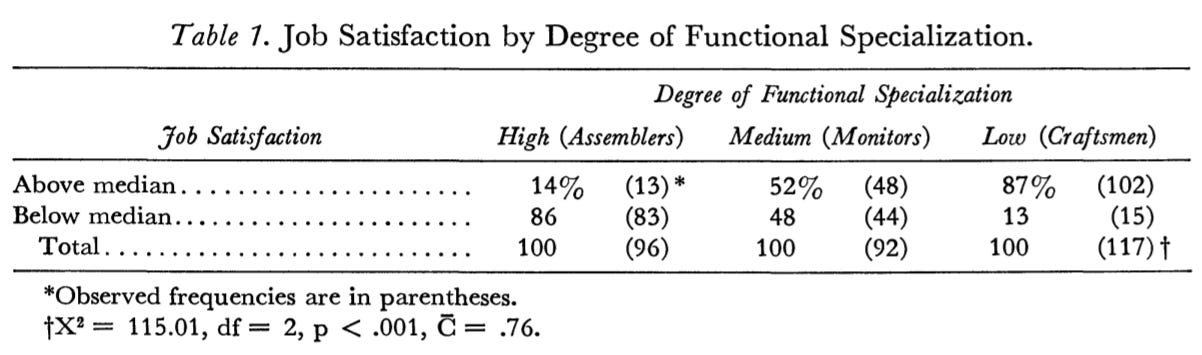

One way to see this is anecdotally, reflected in the satisfaction rates across professions. And 'does increasing specialisation cause alienation' isn't a new worry. Functional specialisation creating alienation and showing up in job satisfaction was a paper published by Jon Shepard in 1970, so we've been worrying about it for a while.

The sheer number of studies consistently reporting the negative effects of functional specialization and the benefits of job enlargement means that they cannot be discounted, although some are open to methodological criticism

This shows up not just in the fact that professions will become obsolete, but through the very morphing of those professions. It also creates a barbell shaped impact on the types of jobs that exist.

Employers also seek to increase efficiency through “disintegration” of the most highly paid jobs (McKinsey, 2012). This means routine tasks are separated from the job and automated or reassigned to lower skilled staff, a practice used in healthcare, engineering and computer science, for example.

The consequence of the slicing and dicing is that more jobs become like APIs, to be called on when needed. For instance, if you look at what a bank manager used to do, that's changed dramatically over the decades. Do you even know who your bank manager is? Centralised credit scoring made lending mechanised since the 90s and that's completely changed the job.

The modern equivalents, even with the same title, are basically high pressure sales folk focused on selling credit cards and insurance. Centralising expertise through creation of outsourced "centers of excellence" and removing authority and insight from counter staff has made most of them pure cogs. Bank branches are effectively as interesting as telephone booths for their utility.

(If you ask bank managers by the way, they would also explain how this led to the credit crisis.)

Same for doctors. The public reporting on it varies from a third of their work being paperwork to two thirds, and in either case it is constantly mentioned how much this has increased.

Previous estimates such as from this 2005 study in Annals of Family Medicine were that paperwork consumed a third of physicians' time. Thus, in a decade, paperwork has gone from being a large chunk to a majority of a doctor's time.

There are other studies that say its only about a sixth of their working hours, but has the best sentence I've read in this area.

More extensive use of electronic medical records was associated with a greater administrative burden. Doctors spending more time on administration had lower career satisfaction, even after controlling for income and other factors.

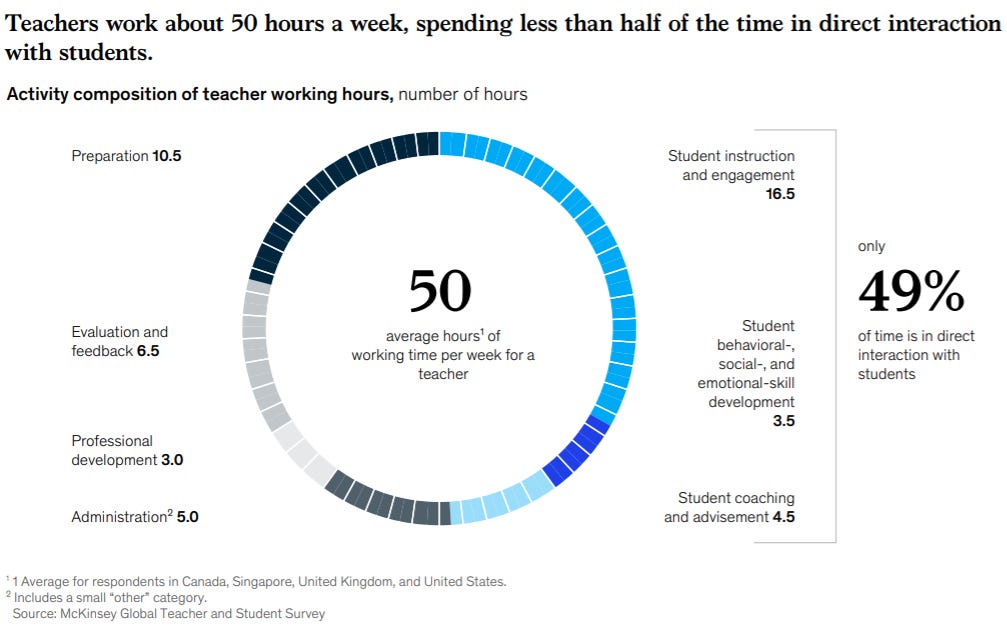

If you look at teachers, its similar. Full-time secondary teachers spend almost as much time on management, administration, marking and lesson planning each week (20.1 hours) as they do on actually teaching pupils (20.5 hours).

This isn't a weren't things great in the good old days take, but it's a things are better but we seem surprisingly alienated anyway take. Maybe the search for meaning is much harder when we are but nodes in some giant connected network. And maybe the increasing hunt for legibility over the decades has been a net positive even!

But it is true that for a large enough number of professions if we'd done the job a few decades ago we'd have been much happier, and the job would've felt less mechanical. I'm not saying this is bad in aggregate, since its the outcome of an increasing hunt for legibility, coming with scale and increasing specialisation, but it does seem something that needs to be acknowledged at least, if not addressed.

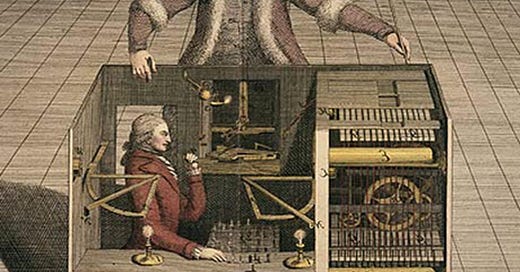

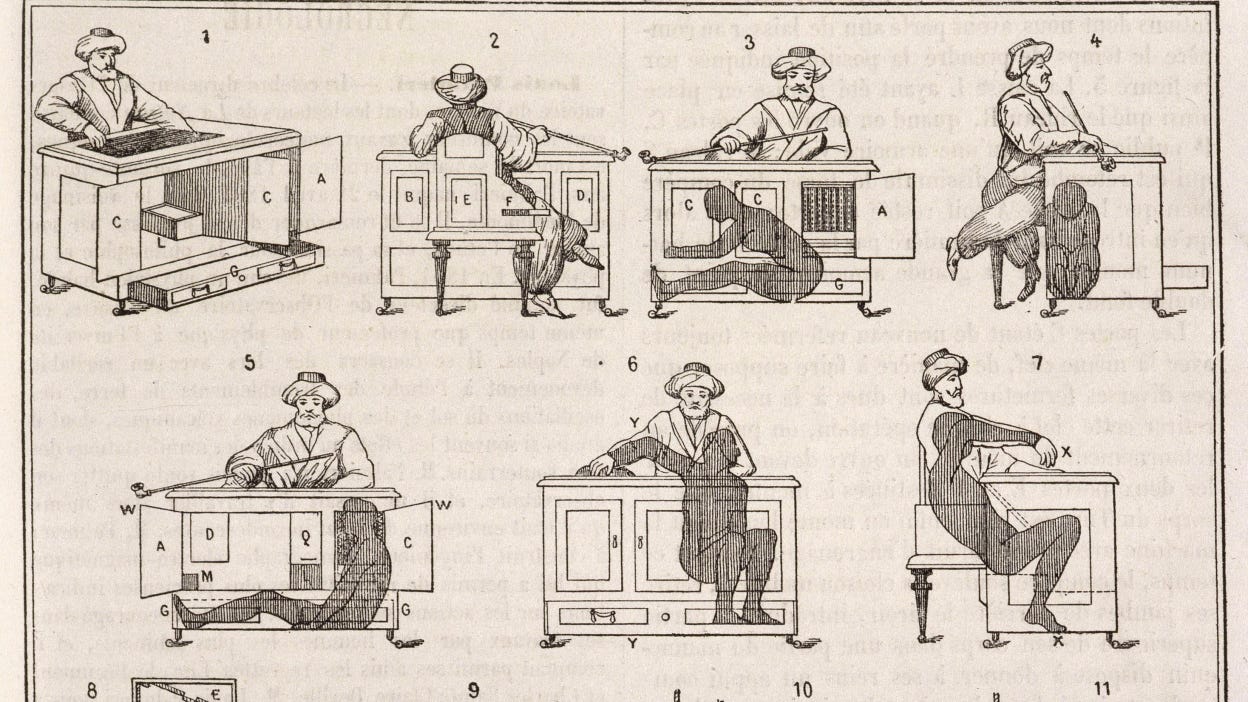

The alternative to the Mechanical King is the Mechanical Turk. The mechanical turk makes humans act like machines too, but only to valorise the machine rather than dehumanise the person. The mechanical turk makes you go "wow, how can a machine do that", instead of going "huh, a machine could do that".

The Mechanical King is a human acting like a machine where the actions seem simple. The Mechanical Turk was a human acting like a machine where the actions were human-level complex.

There's an interesting anecdote here. In the early days when cars started being a thing, the worry was that most people would fall asleep at the wheel and couldn't be trusted. Unlike a horse, who lets your attention wander, a car requires you to pay full attention at all times. Seems to me they modelled the driver as a mechanical king, with mostly administrative involvement while the horse took care of the tough bits.

In the modern days of self driving though, we think about drivers as mechanical turks. They do the hard bits, and when we think of moving part of that burden over to software we worry that the software isn't good enough. That we'd still have to stay vigilant at the wheel, regardless of autopilot.

Work used to exist as another medium through which people built their identity. Lawyers and accountants, despite the fact that they seem mechanical, maybe aren't mechanical kings, but mechanical turks. The parts of the job they enjoy are the part where they're not forced into administrative roles but where they can deploy their expertise in corner cases.

And when we hunt for efficiencies in our systems, as we inevitably do through technology, we should remember that people aren't made to be mechanical kings. They prefer having a domain that's theirs, expertise that they can deploy, judgement and personality they can bring to bear.

Each individual bit seems a small price to pay, a box to be ticked, a form to be filled, a reduction in role definition, but it adds up. But the more of that gets taken away, the less we'll be able to craft a world that brings meaning to us all.

That's a good piece, managed to scare me.

I don't want to sound too "communist" here, but isn't it impossible to run a shareholder corporation without some extent of employees acting like APIs ?

People with complex functions can easily jump to "hmh, I and my team could be doing this all on our own... why exactly are we giving other people a x0%" cut? This does not happen if jobs are swappable enough. Too many people would have to coordinate, and even if they did, you lose a 1-month severance package and are off to hire new ones.

Most professions that you mention (doctors, laws, accountants) seemed to do solo work until not long ago, and it seems like the recent increase in dissatisfaction correlates somewhat with a move towards corporations, which have other advantages that can compensate for sub-optimal work (e.g. is it more important for long-term success that a hospital has good outcomes or that it has good advertising and the ability to accept a lot of different insurances?)

However, a summary look at private vs public market value would contradict this, given that the former is increasing and is somewhat of a proxy for "workers owning their company" (as in, in most cases, it isn't, but it's more prevalent than in public companies)

Bank managers seem like an example that contradicts this though.