It wasn't luck that made them fly; it was hard work and common sense; they put their whole heart and soul and all their energy into an idea and they had the faith.

Garages play an outsized role in any history of innovation. Steve Jobs and Wozniak started Apple in Jobs’ parents’ garage in Los Altos, California. Jeff Bezos started Amazon out of his Bellevue, Washington garage, selling books online. Larry Page and Sergey Brin started Google, about a decade after Apple, in Susan Wojcicki’s garage in Menlo Park, California.

This isn’t a modern phenomenon. Hewlett Packard, one of the original garage startups, was founded in 1939, and started by making an audio oscillator.

They rented a small garage...The rent was $45 a month and with that lease agreement, one of the most important companies in history was launched. The name Hewlett-Packard was chosen by the flip of a coin.

It’s not just silicon valley either, Harley and Davidson started their famous motorcycle company in their backyard shed, in Milwaukee, Wisconsin. Yankee Candle company started out of a garage. So did Mattel, starting with picture frames and soon toys.

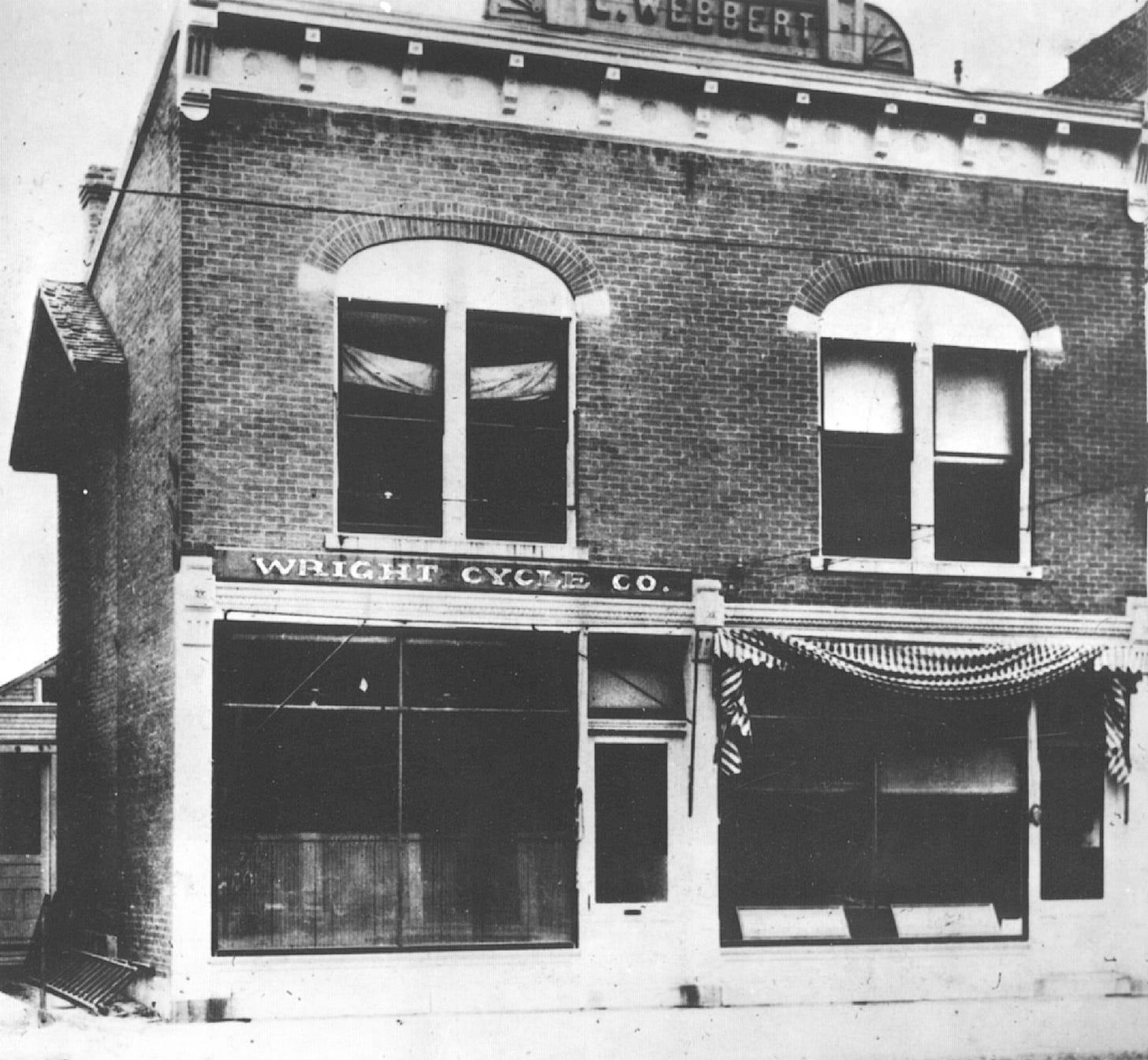

Lotus cars started in a garage. And while its not a garage, because cars weren’t around back then, Orville and Wilbur Wright did much of their aviation R&D in the back of their bicycle shop.

And;

They were not the first in the field of mechanical flight, nor would they achieve the first powered flight, but they possessed what others lacked in sufficient measure – sound training, ingenuity, persistence, a faith bordering on the absolute in the eventual success of their effort, and the good judgment required at each step of their progress.

Philo Farnsworth, of television fame, did much of his early experiments in a lab set up in his garage. Lego got its start as a toy company, where Ole Christiansen started building wooden toys in his carpentry workshop.

Or, even more famously, Walt and Roy Disney started their first studio in their uncle’s garage in 1923. They made Alice Comedies.

The list is endless.

What is it about garages that evoke such stories?

Part of its circumstantial. They were spaces in many homes that weren’t fully utilised, were somewhat separate, where you could host external people and tinker with weird chemicals or electronics. But there are more spaces, though none so evocative. Under Armour started in a basement. GitHub started from a home office as a side project.

The bigger part amongst all of these though were that the garages were the points where they coalesced - where iconoclastic tinkerers tried to make cool things they could on a shoestring budget with minimal interference.

They could somehow convert their passion into a project to work on, often sinking enormous amounts of time and effort, just because they were interested in seeing the result. They were also pretty sure they knew a secret that others didn’t, and it was only a matter of chipping away at a seemingly intractable problem before it opened up.

The minimal interference is not just from management or bureaucracy, but from the ideas of the market or customers too. These were fairly pure areas of commerce, closer in spirit to the hardware version of “let’s build an app and see what happens”.

And most interestingly, neither the problem selection nor the shape of the solution relied on large efforts to validate, beyond the internal validation that comes from being a nerd.

Now while the garages are a modern phenomenon, when you zoom out they are the natural descendants of the older modes of building technology companies.

In fact, if we forget about the last decade and half of entrepreneurship, the world actually looked very different. Many fewer mahogany tables and foosball tables. The largest companies, the ones you’d think of as technological behemoths, were big, often manufacturing companies who built physical things. They too had origin stories that often get forgotten, but which are very similar to the garage startups.

Boeing, for instance, got started with William Edward Boeing got obsessed with airplanes. After having made a fortune in lumber, he bought a hydroplane for $10,000 in 1915, more than a quarter million today, got dissatisfied with it and decided to work with Conrad Westervelt to create a better plane. From Boeing: Higher, the book by Russ Banham.

Boeing began his enterprise during the heady days of the Seattle real estate boom. His first ‘factory’ was a ramshackle wooden boathouse on the banks of Seattle’s Lake Union.

And then they built the B&W Seaplane. So they started Pacific Aero Products Co, which became the Boeing Airplane Company next year.

Now, this isn’t the exact same as a garage startup, but its startlingly similar. It is how many large companies got their start. An obsessive founder funded deep tinkering into a subject they were obsessed about, and created something great in the process.

Other industrial giants are also similar in their origins. Lockheed got its start by the Lockheed brothers, two obsessive self-taught engineers and aviators, trying to build a hydroplane. Initially funded through their savings and helped along by friends, family and some local businessmen who admired their chutzpah.

Glenn Martin, who later merged his eponymous company with Lockheed, got his start by building his first plane in a rented church. Even though, on his first attempted flight:

Martin gained a feel for the plane’s controls as the craft bumped along across a pasture and stalled at the far end of the field. Martin climbed out to re-launch the propeller himself—an unwise tactic with no one at the controls—as the engine caught and the plane lurched forward. The edge of the propeller clipped Martin’s hat as he dove under the wheels and the plane passed over him. All he could do was hold on as the craft dragged his feet, and the plane turned circles and eventually collapsed in total ruin.

Despite ceaseless mockery from his fellow Santa Ana residents, Martin remained undeterred. He headed back to his “factory,” a former Methodist church he rented, and started anew.

And there were spinoffs from Lockheed too, like Jack Northrop, who left Lockheed to build Northrop Alpha all-metal monoplane in 1930, and continued innovating

Or, as Henry Ford said, in People’s Tycoon:

The first Ford cars were assembled by two or three men in a little workshop behind his [Henry Ford's] home...his goal was a simple, practical car for the masses, but his work proceeded by fits and starts.

Or, to stay close to the garage motif, Rolls Royce got it's start with two gearheads, the aristocrat Rolls and the engineer Royce, who thought they could figure out the way to build a new, better car. It started when Royce, dissatisfied with the cars of the day decided to make one of his own. So he made one in Manchester in 1904, Rolls saw this and the partnership was born.

These industrial behemoths too were labours of love at the beginning. It's funny to look back and see that they were also built because the right combination of talent, obsession, tinkering spirit and the bare minimum of money came together for them to create the things that they were obsessed with. In these cases automobiles and airplanes, who can blame them!

The commonalities are necessary of course, but not sufficient. The stories are about passion and obsession, small tight knit teams, high degrees of experimentation and autonomy, and forced resourcefulness. These are all needed, even if they are not all that’s needed. There are plenty of stories of obsessive founders who put their heart, soul and brain into a piece of work that never quite worked out. Even amongst the ones we looked at, Disney failed more than once, the studio went bankrupt after laugh-o-gram films.

So did others. My favourite failure might be General Magic, who wanted to create a personal communicator in 1990s. The team had Marc Porat, Bill Atkinson, Andy Hertzfeld, Macintosh veterans with a (clearly accurate) vision that portable communicators would take over the future. Andy RUbin was there, before cofounding Android! As was Tony Fadell, before Nest Labs. And many many more legends. But despite all the talent, clear obsession, technical prowess, and a lot of money, the infrastructure just wasn’t there to make it work.

But in the success cases, assuming they weren’t taking the market for granted, the core for the work was focused, finding a small advantage in an area they were obsessed by, and using their own fortunes and time to tinker around until they were satisfied.

There was clearly some external confluence, a new development, that the founders were obsessed with. Airplanes, cars, wiring motherboards together to create computers, there’s this feeling of a new wave cresting, and the only way to be in it is to jump in and play!

There’s also the flip side, an obsession. From The People’s Tycoon, and Ford’s corporate history.

Ford was consumed by a desire to build a light, affordable, and durable automobile.

This is a through line across the garage startups of all stripes.

And then there’s the resourcefulness. Almost by definition they were all young and immature, with limited resources if anything at all. But rather than making this a liability, this is the epitome of constrained optimisation. From Skunk Works, the story of Lockheed.

Give us an impossible deadline and a budget made of spare parts, and we'll give you a flying machine no one's ever seen before.

Or Dave Packard in The HP Way:

We started out with $538 in capital and had at most eight people to do all the work.

There is also the added benefit of having minimal distractions. Not just because it was small, there’s a stunning lack of bureaucracy and an enormous amount of flexibility.

The Skunk Works' approach involved streamlining the process and eliminating all bureaucratic obstacles. A small, highly motivated team with maximum flexibility and minimum distractions could operate virtually free from the rules, procedures, and organizational barriers that encumbered more conventional programs.

This carries through to the team having ownership, to almost force a sense of play. From Skunk Works again:

Kelly [Johnson, head of Skunk Works] knew his limitations. In an endeavor as complex and far-reaching as the U-2, he could not micromanage everything. The key was...surrounding yourself with the most innovative, self-motivated engineers imaginable.

And;

Kelly also demanded absolute loyalty from his engineers. In exchange, he offered freedom from the mundane, a sense of ownership and the opportunity to work on some of the nation's most secret and exciting aircraft programs.

While many iconic companies like Nike got their start as a pure business, importing Onitsuka Tiger shoes from Japan and selling at track meets, the almost prototypical story of a business emerging from sheer commercial will, the garage startups and their predecessors are different. They emerge from obsessive play.

There’s talent and luck and skill for sure, and there’s also a new technological wave to help surf, but there’s this trend of taking play seriously. Taking an object of obsession, and actually going deep into it, that seems to be a crucial part.

I don’t know why it is that garages became those spaces so perfectly conducive to outsized innovation origin stories. They are the successor to the old days of crazy innovation, of tinkering on a hydroplane with your fortune and a twinkle in your eye. But I do know we ought to find an answer to how we can create more such spaces, and encourage following the kind of passion that leads people to want to spend all their time tinkering on a problem, and try our damnedest to not let overthinking destroy it at the most nascent stages.

Thanks so much for making this amazing list of the importance of garages - cheap space that is protected from rain and theft, and close to someone's bed. In addition to their business contribution, they have an outsized role in U.S. culture - so many bands started in garages. Cheap space to practice.

When I lived in the U.S., that is the first thing I noticed compared to Europe or Japan. This space where I could build stuff for fun. Here in Europe they try to compensate by giving some cheap rentals for start-ups - but a bureaucrat choose who gets to use it, and it's far from anybody's home, so no way to truly let your energy in like you could in a garage.

I think that's just another sign of how real estate costs slowly smother economies. If you have to have sufficient income to pay for expensive space to even start anything, well not much can get started. Americans underestimate how well cheap space has served them.

If it won't work in the garage it either won't work, or you don't understand it enough to move it out of the garage... no perfect principle, but in my experience it holds in most cases. Thanks for writing this.