Talent hits a target no one else can hit; Genius hits a target no one else can see

Arthur Schopenhauer

I

Peter Thiel likes to say that our obsession with dystopias is somehow emblematic of our inability to innovate and technological pessimism. I have a similar obsession, except it's not about dystopian science fiction but it's about our depiction of intelligence in popular culture.

Examples:

Dr. House, an exceptionally talented, smart, genius doctor, who spends his vast intellect solving one crazy case at a time and playing fantastic pranks

Scorpion, a TV show about a team of geniuses, who act as government contractors and solve difficult cases through extremely fast and eerily accurate Fermi calculations, self pity for being geniuses, and Macgyver-ing

Sherlock, the paradigmatic titular genius who solves crimes that nobody else can figure out, with his vast inductive intelligence that notices where someone's been through an encyclopaedic knowledge of mudstains

Tony Stark, the Iron Man himself, the prototypical example of genius-as-a-superpower, who uses his intellect for ... slightly better defense weapons primarily and asking his version of clippy to solve engineering challenges (and the occasional time machine)

See a pattern? They're all geniuses who solve puzzles. Nobody invents anything. Nobody even discovers anything, despite it being a D plot in some Scorpion episodes.

Now some of this is of course screenwriting magic. Who wants a tour de force of the aftermath of inventing clean energy like Ironman did, replete with the seventy five committee debates at the UN? (Me.) But to brush this aside is also to fundamentally misunderstand genius!

Is this what our collective conception of genius is? The ability to spot if someone has been lying or visited the Empire State Building, and the ability to land a devastating quick quip while building Rube Goldberg contraptions?

Tony Stark is the one here that frustrates me the most! After he just about discovered a limitless power source, he kind of loses interest in the whole invention thing. In fact his most amazing invention might be Jarvis, which actually invents almost everything anyway. It's like a Siri that works in the real world and without the need for five spelling corrections. How is that not his most famous creation? It even creates a frickin new molecular structure that his father hypothesised about based on some half-assed questions from Tony. How is Jarvis not everywhere? Why can't every researcher in the world go "Jarvis, analyse the molecule and tell me about it," or "Jarvis, what impossible metal would contain these properties, and by the way can you manufacture it for me?"

Another part of the answer might be that it's just really hard to show thinking in a TV show. You need something more actionable, which means you look for more exciting happening. And what's more exciting than solving a problem of how to survive jumping from space without a chute, as opposed to actually inventing something new like a new piece of software to analyse the results of someone jumping from space.

But I think it's deeper than that. We just have this visceral obsession with geniuses as those who can connect seemingly disparate ideas and are incredible at induction. That's also why we love them for being quick witted. We've confused speed for velocity. And as it's crept into society, those same hallmarks became what we look at when trying to ascertain if someone's a genius.

II

The historical conception of genius started as a belief in a literal spirit that would being with it ideas that would change the world. Like a guardian angel that sits atop your shoulder (probably) it would help guide you. And not just you, the human, but if you happened to be a location or a place, you'd have a genius too. So if you were a giant mountain, a genius loci would reside within. Or if you were a particularly awesome vase, you'd have a genius too.

This way of thinking quickly developed into the theory that everything has a soul and everything has a spirit and that's of course immediately dilutive to the myth of the genius! If everyone's special then no one is, yadda yadda.

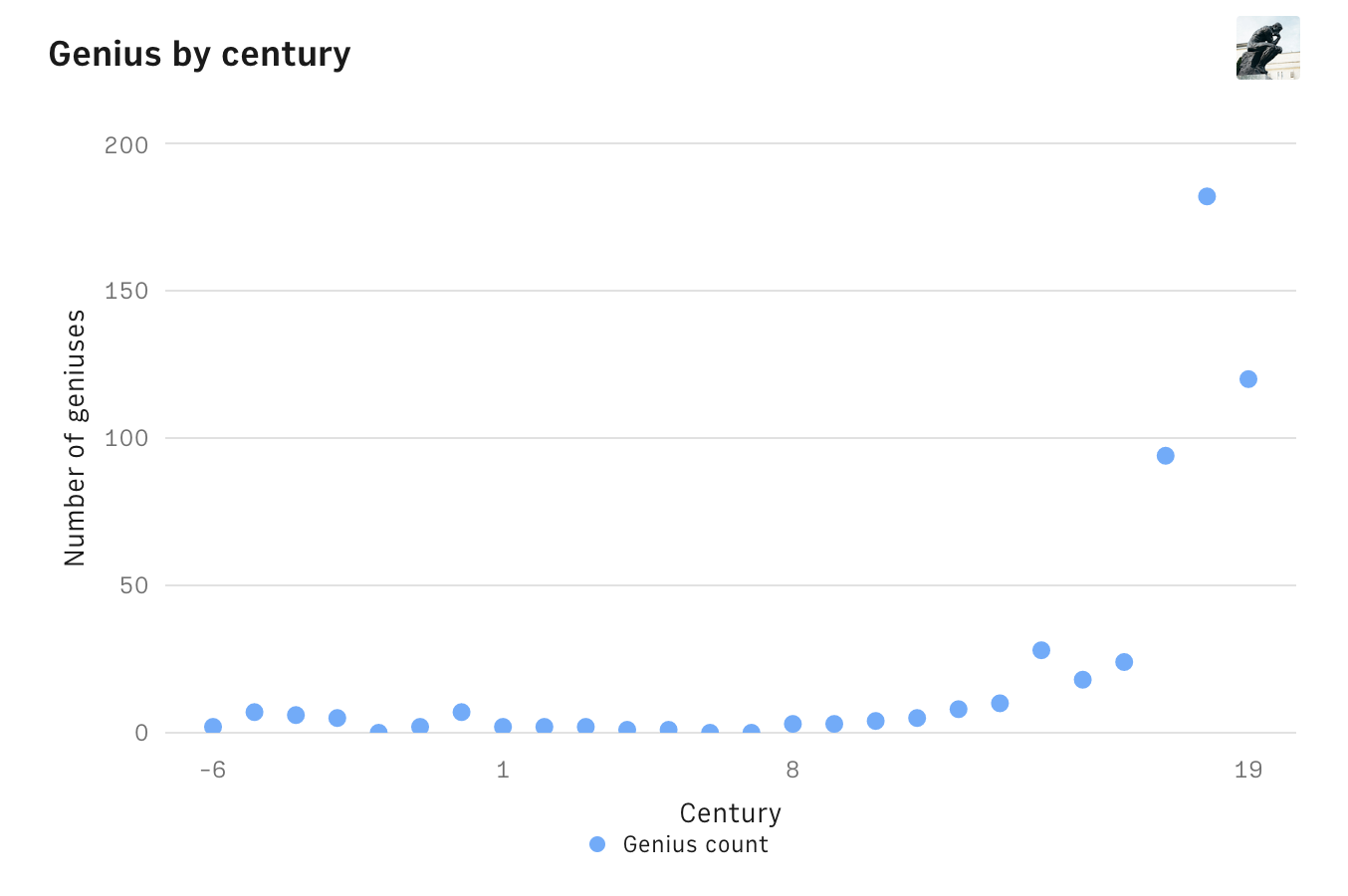

But when you unpack the question a little more and start to have a look at whom the world actually considers geniuses, we start to see some patterns. To go beyond the usual suspects, I found a list and chose the top 500 (at least to start with because at that point it started scraping the bottom of the barrel), and the people selected are no longer what one would consider universally regarded as geniuses. Analysis and data here.

Naturally, a larger percentage of those identified are from the West, and you see that in the data.

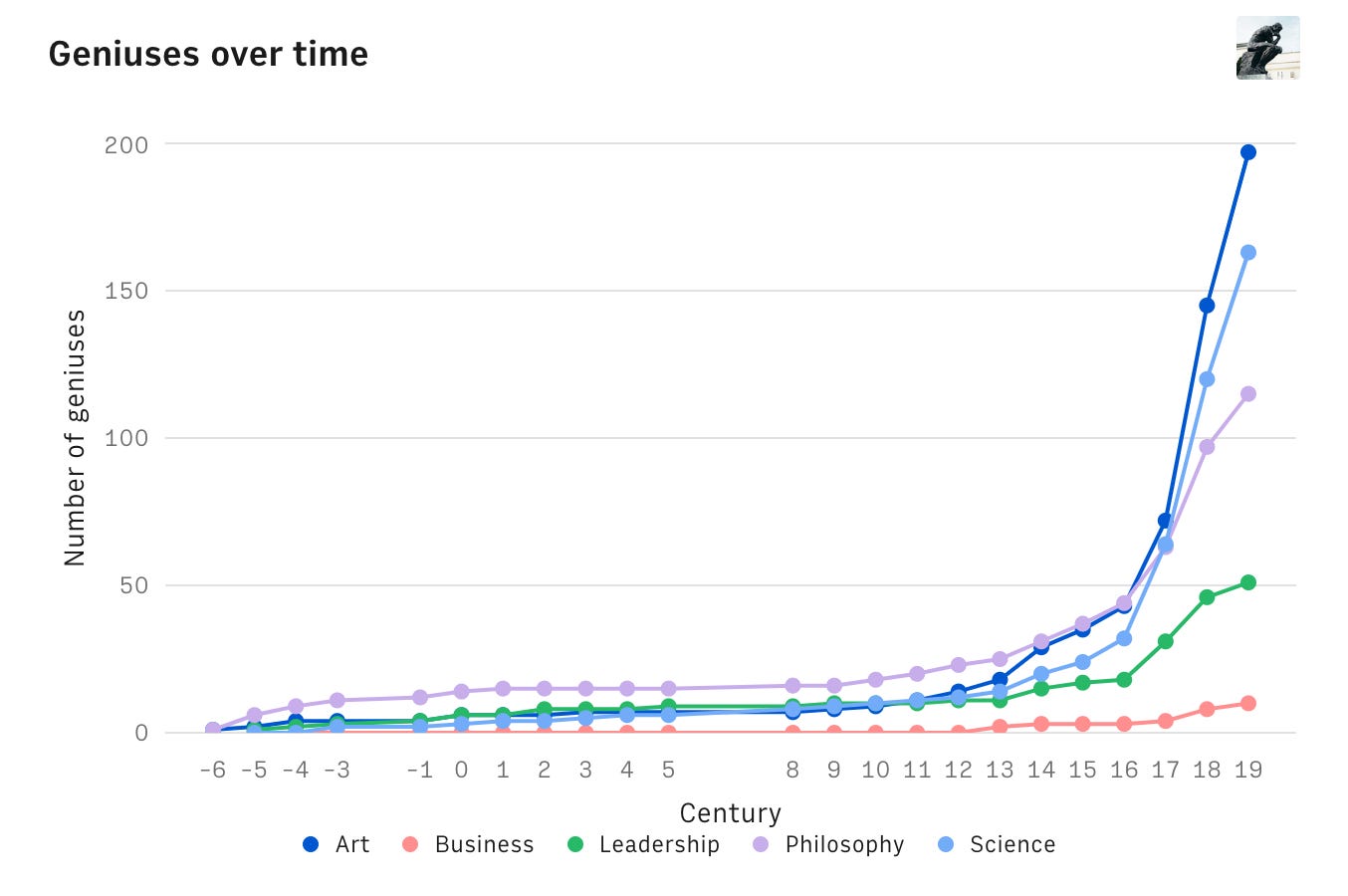

While clustering them together, we can see that there have been broadly speaking five types of geniuses who got recognised around the world:

Leadership genius - the paradigmatic examples being Alexander The Great, or Napoleon

Scientific genius - Isaac Newton, Charles Darwin or John von Neumann

Artistic genius - Shakespeare, Picasso or F Scott Fitzgerald

Business genius - Ford, Steve Jobs or Musk

Philosophical genius - Aristotle, Hume or Wittgenstein

What's fascinating is that each era had conceptions of what a genius is. In pre-modern times it looked like philosophers and military geniuses took the crown. In middle ages we have military geniuses yes, but we start seeing scientists make a bigger appearance in the aggregate numbers.

And in the modern era like almost never before, we see the rise across all fields, with the enlightenment clearly standing out. Starting with crossover figures like Edison, but soon with legitimate business geniuses like Ford and more, we see polymaths (primarily scientific polymaths) increasing in numbers.

Today there's an overwhelming number of Business geniuses too, unlike most eras before. When you go lower than 500 you start seeing more of them. Elon Musk is a genius, he's somehow disrupted three of the most notoriously regulated and ossified industries on the planet. Bill Gates is a genius too. Even if it's only in business. He started a company as a teenager and became the richest man in the world, which he still would be by a giant margin if he didn't decide become the biggest philanthropist instead. Steve Jobs. These are the figures standing atop the zeitgeist of the moment.

III

So let's cast an eye back to the fictional geniuses to see what we think they look like. I collated a list of 40 to start with. It's interesting how many are still scientific or quasi-scientific in nature, which relates to the observation above of actual geniuses where also science seems dominant. It seems our idea of what or whom a genius is primarily seems to revolve around their ability to understand that arcane world.

What's striking though about this is that the scientists depicted in art often don't do anything. Mostly it seems to be some combination of building elaborate contraptions under tight time and resource constraints, and being really good at reading people (or occasionally being really bad at navigating real life).

Almost none of them invent anything that changes the world in any meaningful sense. They don't even try! Their existence has barely any technological ripple effects. Again, Tony Stark. The movies show that his inventions around sentience in robots caused a worldwide catastrophe by creating Ultron. Keeping the doomsday mythos out for a moment, isn't it interesting that despite Ultron the broader universe doesn't feel like one where sentient robots are ever-present? And Tony's not even a regular absentminded scientist oblivious to the real world. He's a businessman who's partial to lamborghinis! Where's his business sense?

Or Hermione, the most talented witch in her generation, shouldn't she have done a tad more than just get A grades? Invent a spell maybe? Or Dr House, the medical genius, shouldn't he have done at least something that goes beyond saving one patient a week? Maybe a new device or procedure or even a diagnostic technique?

The problem with this is that our cultural vision of what a genius is seems filled with notions of someone who solves impossible puzzles impossibly fast. Is this what we want to encourage? Roger's Bacon had a fantastic post about the myth of the myth of the lone genius, and part of the assertion there was to ask how we want people to think of themselves. Do we want them to believe that genius is somehow unattainable unless they can invent Jarvis out of whole cloth within the duration of a pop song, and can read people like poker pros.

It all means that if you do believe that you might be a genius, or even that you have the proclivity towards it through some external factors, you'd probably do very well to completely ignore what the cultural world actually says geniuses are like. The fact that you don't look or act like the cultural icons has no informational content or value.

But do prospective geniuses actually think they're not because they don't act like Sherlock Holmes? Well, yes. It affects them in all sorts of ways. They don't attack the harder problems because they think they're not smart enough. They don't apply for that grant, write that paper, create that show, write that novel or start that company. There's a large subset of literature around great prospective entrepreneurs who haven't been discovered because they didn't think they had it in them. There's zero reason this shouldn't also apply towards higher levels of achievement!

Guzey has a paean to the idea that genius isn't about being perfect across all dimensions, but being great at one or two. It suggests that our constant comparison is what makes us feel like we're not geniuses. That we feel that unless we're at the very top of whatever chosen profession or vocation, there's no point. Which is yet another way to exclaim that what we think genius looks like, as informed by what we see and hear and read, has limited correlation with what genius actually is.

You don't need to know everything about everything. You don't need to have the fastest quip or be a champion of the bon mot. You don't need to be a prodigy. There's a lovely article comparing the likes of Picasso, who could paint a masterpiece almost at random, with a Cezanne, who would tinker with his paintings ad infinitum to produce his masterpieces. They're both valid and we should acknowledge that.

Appendix

One of the interesting nooks of this topic is what happens to child prodigies when they grow up. It was a field with a ton of non intuitive beliefs, especially in ye olde days. For instance, there was a myth that being a child prodigy was bad, because you'd end up being a sicky, lonely loser.

The myth was still very much alive in the 1950s, when Dr. Lewis Terman released his 30-year study of 1,500 child prodigies. In his conclusions, he wrote that child prodigies not only didn’t develop into sickly, lonely losers, but generally grew into well-adjusted, healthy, highly successful adults.

And the overwhelming consensus is that they grow up largely to be successful, well functioning adults.

The argument here is that creativity is what's lacking. The prodigies learn to equate approval from their elders with success, instead of attempting something new or original.

They apply their extraordinary abilities by shining in their jobs without making waves. They become doctors who heal their patients without fighting to fix the broken medical system, or lawyers who defend clients on unfair charges but do not try to transform the laws themselves.

Instead, when you look at geniuses today you largely tell that they like what they do, and they had an intrinsic motivation towards whatever made them successful. Finding what you like is a nontrivial task, and finding that you're good at it, good enough to continue pursuing, is an even bigger lightning bolt.

But it's like the birthday question. If I wanted to find someone else with the exact same birthday as me, the chances are much smaller than if I wanted to find any two people in a group who share a birthday.

Great article! The thing is, literally no one wants geniuses or inventors enough to pay them a living. No one wants to hire people smarter than they are, particularly disagreeable people who will tell the boss that he's wrong, make him feel inferior (which he is). Geniuses don't like being subordinated to midwits, either.

Nor is independent inventing a viable path. If patents were as easy to get as copyrights, or even just as inexpensive, I'd have hundreds at least, but anyone smart enough to come up with many good inventions is too smart to play the game, the "incentives" for innovation are in fact nothing but severe impediments, even punishments. It's about the same penalty as a first-time DUI to file for a patent. Patents are around $10k, which only gives a license & duty to sue infringers, suing will cost about $1M - $2M per case, and has a poor win rate, at that. At least 98% of patents never earn out their filing fees, let alone attorney's fees.

The number of inventors that make a living at inventing is pretty close to zero, at least two orders of magnitude lower than the number of patent attorneys. There is no market for patents, let alone inventions.

Every invention is competing not only with every other method of doing the same thing that has ever been published, and specifically against the ways that market incumbents have sunk capital into, capital which will be stranded by innovation, but also against every potential way of accomplishing the task that might be conceived before the invention has a chance to earn out the investment required. The transaction costs for what sporadic patent deals do occur are far more than the inventor can expect to get. Any valuable patent will get reexamined until it's invalidated.

And the worst thing is, even if you don't patent, but instead publish an invention, you effectively not only lose all rights, you taint the IP so that no one can seriously invest in it -- it's unpatentable (worse, the patent will probably issue then get invalidated after expensive litigation) and not a trade secret. The smart move for inventors is to keep valuable inventions secret, even if they can't develop them, so as not to spoil things for someone who could make a go of the idea later.

Which brings me to another problem, which is that a good inventor can come up with a dozen or more inventions per month, culled from hundreds of ideas, but the system has no real division of labor to allow inventors to just invent - no, to profit from any idea requires all the time and money investment and the traits and skills of a successful startup founder, which are mostly incompatible with such inventors' personality types. Even when such a rare Musk-monster is to be found, even when he isn't crushed by one adversary or another and manages to get access to capital on good terms -- there is only enough time in life to implement a very few innovations; spending the time on entrepreneurial / corporate / social BS instead of on the mind-play of invention costs that inventor -- and society -- nearly his whole output.

That comes far from exhausting the problems with the system, for instance the fact that universities usually claim rights to inventors' work, even for undergraduates who are paying the school. Businesses also regularly claim the right to legally take employees' patent IP without any compensation, even when not developed with company resources or at company direction. Inventors are thus either shut out of universities and large and tech companies, or they are exploited.

There is a systematic oppression of intelligence -- which is to say, of people with a literally exponentially higher likelihood of solving hard problems. (citations on Rasch measures omitted) In "Do you have to be smart to be rich? The impact of IQ on wealth, income and financial distress" by Jay L. Zagorsky (2007, using NLSY data) found no correlation between net worth and IQ above 100. The correlation between income and IQ is less than 0.3 overall, and nearly 0.0 for intelligence in the top 10%. Those with top 1% intelligence are more likely to have financial hardship than average people.

This is not because smart people aren't more productive,Schmidt & Oh's 2016 update to Hunter & Schmidt's classic paper (which was perhaps the first meta-analysis) found IQ validity for predicting job performance is 0.67, vs. e.g. 0.0 for experience, 0.2 for education, 0.3 for biography. (Table 1, p.71). IQ is in fact the best single predictor of job performance, but it is not rewarded in the market, costing at least $5T/yr. in lost productivity in the US alone.

This post is long enough; let me close by saying that mispriced brains are the biggest economic inefficiency I know of. Putting people with exceptional intellectual ability in control of investment in innovation is the optimal strategy for both profit and long-term good.

Well done 👍