I

A fable. There once was a fictional country with a fictional government who needed to spend some fictional money.

There is a government that needs to raise tax dollars. It decides to raise funds by increasing taxes on everyone by 1%. Everyone hates them immediately and with uncommon vigour.

There is another government that needs to also raise money through tax dollars. It decides that you shouldn't put disadvantaged people under even more pressure than they're in. They increase taxes only on the richer people by 3% instead. Only the richer people hate the government now.

There is yet another government with the same pains. They decide on another tack, because looking at the first government they are rightfully freaked out. So they just devalue the currency instead by issuing a bunch more.

The fourth government decides that people are too much work to make happy, so they tax the companies instead. Just like in the second case, some of the same people end up rather annoyed. What are you gonna do!

What is fair?

One place to find answers is philosophy. After all they've been searching for these kinds of answers for at least a couple millennia. And lo, we find that the philosophical arguments seem to fall into one of three (very) broad camps:

The deontological argument pushes the view that paying taxes is a solemn duty that we all have to participate in. We all have to pay the dues because that's our duty. Now is the duty to pay 0% tax, or 100% tax, or something in between? That is indeed a question. It's all about how you define 'duty', which honestly seems like a thankless task. Without many useful answers.

The virtue ethics argument talks about what constitutes a virtuous life. The virtue is in acting as part of this wonderful society we live in. Let's set the rate so that our collective virtues are maximally used. Tax someone so much that they no longer pursue their highest calling? Don't do that! Tax someone so little that their incentives are all warped to participate in the society? Don't do that either. Just select what you want people to end up doing and set the tax rates and schedules accordingly.

The utilitarian argument argues that we have to increase the net total happiness however we can. So who cares if a few rich people get upset, just maximise the tax revenues by annoying the least number of people. Just do the math people.

Unhappily it seems that none of the above gives us a strong indication to steer us in any particular direction. But it does give some tools to play with to assess our four fictional governments above.

When the arguments about taxation happens in our society, it usually ends up with some combination of "tax the rich" on one side and "tax cuts for the rich" on the other. The idea with the first is almost the same as Willie Sutton's motto which is extremely hard to call, what's the word, moral. The second is an argument for one part of the system using their money in a way that is more useful for the rest of the society - give them control over their tax dollars, and they'll spend it wiser than you (as the government) can.

Neither are particularly convincing arguments.

For one thing, neither talks much about the benefits of their proposal except in the vaguest of terms.

Taxation isn't something anyone enjoys when paying. But its fruits are something everyone enjoys receiving. The fact is that if you've done well in society, you've gained a ton from being part of that society. You can't build a power law curve with only the fat end. The long tails are necessary!

Which means that paying more because you got more is eminently fair.

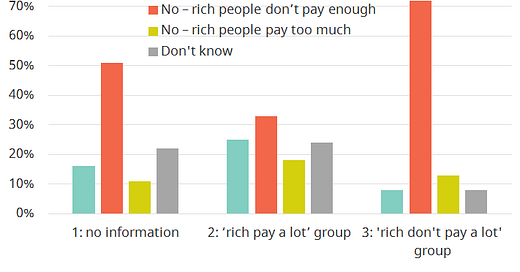

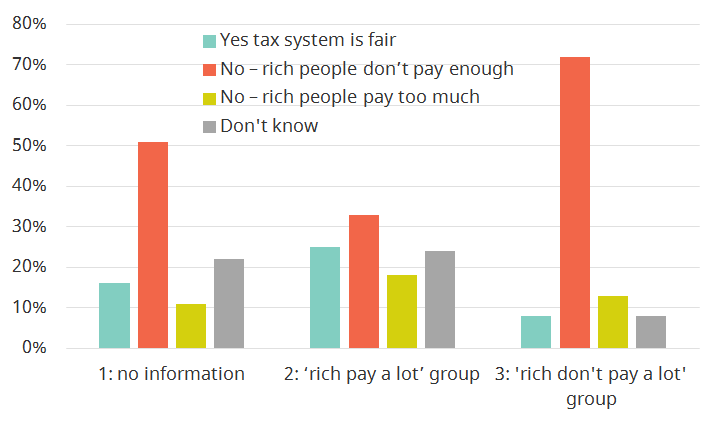

There's a fantastic experiment that was run by IFS (Institute of Fiscal Studies) in the UK in 2017. The experiment:

We recently ran a straw poll to demonstrate the power of information. We asked a simple question: Broadly, do you think the UK tax system is fair? In many ways this is a silly question; so broad that it’s hard to know what use the results could have. But before answering participants were randomised into one of three groups

Group 1 were just given the question.

Group 2 (the ‘rich pay a lot’ group) also received these two true statistics:

The point at which income tax starts to be paid has increased in recent years. 4 in 10 adults now pay no income tax.

The income tax system is top-heavy. The top 10% of income taxpayers pay 60% of all income tax.

Group 3 (the ‘rich don’t pay a lot’ group) also received these two true statistics:

The richest 10% of income taxpayers earn more income than the entire bottom 50%.

Someone earning £45,000 faces the same income tax on an extra £1 of earnings as someone earning £145,000.

The results:

Two sentences, both true, flipped the proportions of answers by c.20%.

I guess the lesson is that what we think of as fair is highly malleable and can change in an instant. What we believe in, fiction or reality, have a disproportionate impact in what we think of as fair.

II

Ok let's get one thing out of the way. Taxation is extremely weird. As I've been reading up on it, most of it seems like one of those funky images that only appear when you squint and look at it sideways.

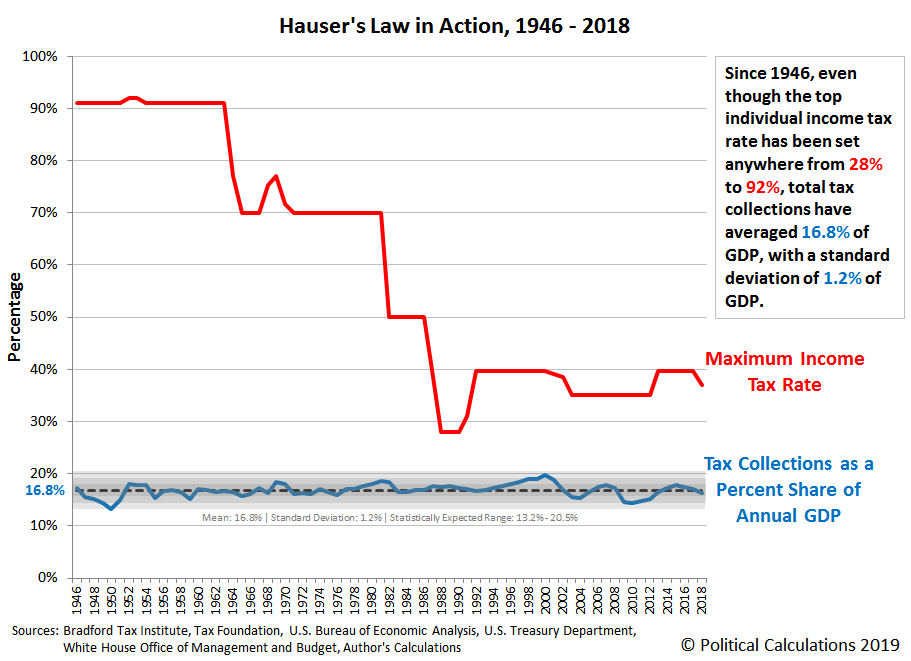

For one thing, despite every change in individual tax rates, the total tax collections as a percentage of GDP seems to be extraordinarily stable. It's called Hauser's Law, and is one of the more counter-intuitive empirical results in economics.

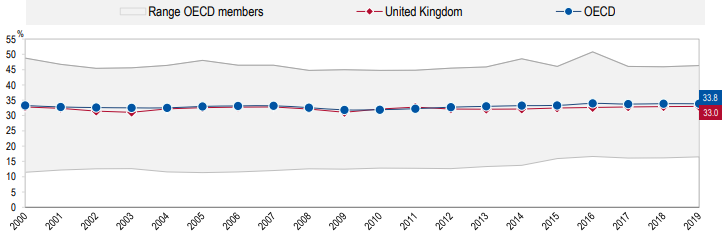

What about the UK or OECD overall?

Looks like the same type of trend here too.

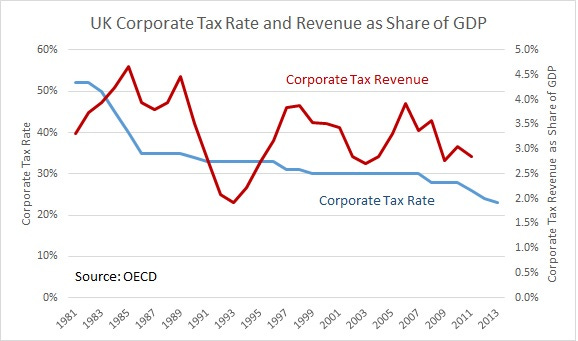

A further look at UK's tax revenue as a share of GDP shows a bit more variability. But it's worth mentioning that the crazy V around 1992 was also coincidental with Black Wednesday, where the British withdrew the pound sterling from the ERM after they failed to keep the pound above the exchange limit. It also made George Soros a very rich man, but that's just colour, and nothing to do with the tax revenues.

The answer here might be that it's a self corrective system. Tax rates aren't determined independent of the GDP, or the expenditures the government runs. If a large proportion of expenses are expected, i.e., they're predictable, then the tax rates would also be predictable.

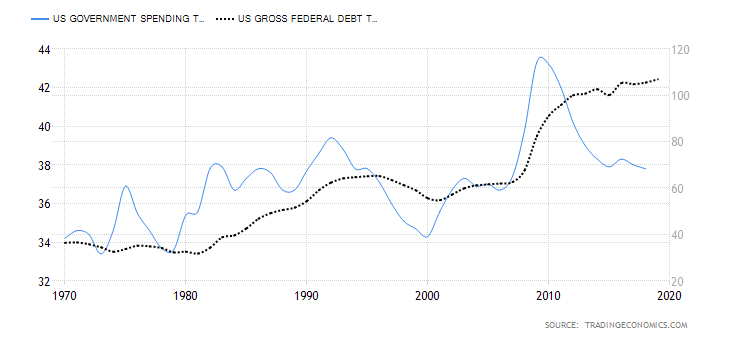

And you would only cut the rates if the collections were being taken care of in some other way. The chart above shows pretty clearly that while the expenditures as a percent of GDP has gone up, so has debt. So the impact on taxation has been to not mess with it too much and finance any extra through debt. It could be a response to over-collection too, and therefore a retroactive adjustment to the way things are.

Evidence: As individual tax revenues have stayed semi-stable, corporate tax revenues have dropped, and social security has increased. When you sum it all together, you get in a pretty tight band. Also, 1968 showed a spike in collections due to a rise in income top tax rate which increased collections, but that came back down of its own accord over the next couple years.

With this finely tuned a system, all parts of which seems to be semi-adversarial in nature, perhaps it's only sensible that the outcome seems mighty stable. Mutual conflict amongst different, and functionally independent, assets sum to similar numbers with a high enough probability. Just like rolling a die repeatedly brings a nice Gaussian distribution. Well, binomial, but close enough for government work!

III

Ok, back to the question of how we actually determine what's fair in our fictional country.

Naturally whichever philosophical school you choose to believe in has an influence on the decision that you need to make.

What's really interesting is that this only works if you believe in a fiction. You have to believe that there is a thing called 'collective will' that is spread through 'society', where it manifests itself through government policy, created as it is through painstaking horse-trading that theoretically should have some form of market clearing price associated with it.

The collective fictions we believe in guide our actions, and also guide our options much like any environment guides the evolution of its organisms.

So, for instance, if we believe that in general all parties in a particular economy have their interests aligned, then that is a world where you don't need to do much specialised means-testing to enforce any policy.

Or, more realistically, if there are conflicting priorities amongst the different groups within the citizenry, then knowing where the fault lines lay is helpful in crafting a narrative that can bring about the changes we desire.

When we try and analyse what's fair, there is a sentiment we are trying to satisfy inside us. A sense of fairness means, among other things, a sense that equal efforts engender roughly equal outcomes. Even if equality in outcomes is an extremely crude measure to attach to something, the fact that equality of efforts means little is, at the very least, contrary to how people perceive it. And that's where a large part of the fiction we live by fails.

Lots of arguments for higher taxation argue from necessity (we need the money). But that's also manifestly unfair. A better argument would be in terms of fairness and rationality. For instance, an argument that the richer in the society should pay their fair share could be:

If you calculate the fair share as a percentage of the benefit they extract, it ends up being higher

If it's as a percentage of their actual life footprint it should be higher - the richer do consume more after all

If it's as a proportion to their earnings overall it should be higher - with the assumption that if you are earning more, clearly you're benefiting from this society more

The key is also to recognise that the outcomes you're seeing are not just the result of a linear series of variables. It's the explicit realisation that when we are behind the veil of ignorance, there is likely to be a power law exponential distribution in some key variables, like income and wealth, and this means that being at the far end of the distribution isn't "just desserts" but rather the inevitable outcome that some would have gotten anyway, even if you couldn't predict who that someone was ahead of time.

The issue of taxes works well as it's directly linked to the largest coordination effort of all, an entire society pulling together to self govern. It's a way to understand almost the very basis of what we could consider as fair. Much like monkeys sharing grapes or kids sharing candy, the assessment if often innate and pretty strong. These studies on fairness also have a couple of the most fun sections in academic journals:

Although there exists substantial cultural variation in its particulars, this ‘sense of fairness’ is probably a human universal that has been shown to prevail in a wide variety of circumstances. However, we are not the only cooperative animals…

Here we demonstrate that a nonhuman primate, the brown capuchin monkey (Cebus apella), responds negatively to unequal reward distribution in exchanges with a human experimenter. Monkeys refused to participate if they witnessed a conspecific obtain a more attractive reward for equal effort...

One lesson clearly is that if you want to have fun as a scientist, clearly you need to go into social studies where you can give them cucumber slices and grapes.

The second is that the stories we tell ourselves are important. It's what helps us triage the universe of possibilities into a few manageable narratives. And those narratives in turn guide our philosophical beliefs, which guides the policies we feel are appropriate and fair.

The argument from fairness here is that you have to link the outcomes with the fiction we live by, that as a society we will try and uplift everyone, make the power law not just steeper (the best of the best get outsized rewards) but also fatter (we all get pulled up together). It's the reason we argue about raising the minimum standard of living. Apart from utilitarian reasons about enhanced productivity and reduction in GDP drag, it's also the right thing to do by both deontological and virtue ethics.

Regardless of the fact that the exact utility of various tax policies is questionable as they all seem to tend to converge to the same aggregate measurements, the distribution of said policies explicitly rely on these narratives. And without a sense of fairness being clearly perceived by a large enough proportion of the populace it's hard to see how we can get to a story that we like enough to follow.