[A wonky exploration of a bunch of issues surrounding stagnant wages. Linked with the polarisation argument made here. Starting point was a review of Alex and Eric’s book though it went far afield soon since there is an enormous amount written in this space. Plus (speculative) conclusions at the end.]

Introduction to the problem

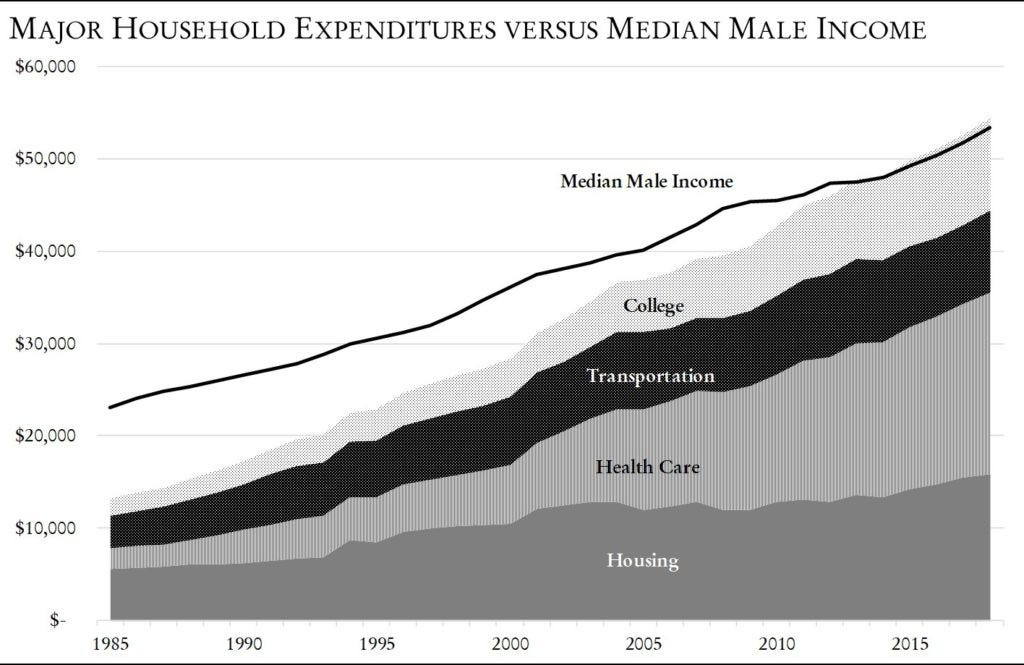

Alex Tabarrok and Eric Helland wrote a free book called Why Are The Prices So Damn High in 2019. It has all the fun of an economics blog and a well written polemic, and tries to answer the question that's at the heart of a major modern ill - that for things we can't live without, the prices have grown at a pace that's, to put it mildly, dramatic!

The question is why. I tried to have a first look at this problem before, with the answer echoing a few of the points that were made more eloquently by Alex and Eric a year ago.

But still, Baomol’s cost disease being the reason for such crazy price delta strikes me as evading the question, primarily because it's the equivalent of saying the prices here are higher because we've made great strides in productivity elsewhere (but not here) and therefore everyone wants to be paid more to be a doctor or a nurse or a teacher. The key being that services don't get more productive to produce while goods are and that delta means that services will get more expensive over time.

The issue being, we're not paying more for teacher salaries. In fact one of the biggest problems is that their salaries are, and have been, pretty stagnant. Same for nurses. Same for construction. None of them seem to be getting paid much more for the privilege. This seems an inverted Baomol's disease without much wage increase, which is no fun.

Alex and Eric answer this by saying that the wages actually do increase over time (pg 22 for instance). But this isn't true globally, much less in the case of teachers and/or nurses which they actually quote! There are some procedural questions too, about how they calculated educational attainment and prices (e.g., conflating K-12 admin with college faculty prices).

Also, is the claim inherently really that healthcare has not increased in productivity? That seems like an extraordinary claim and needs extraordinary proof, which is not in the booklet. Doctors and nurses in the 80s didn't even have computerised records, much less decent labs and all the toys the pharma boys cook up for them to play with. And none of this matters since a doctor's hour is a doctor's hour? Especially when their wages haven't risen all that much?

Which was my biggest question mark. There seems to be a substantial number of places where this effect hasn't shown up. There's been a crazy divergence in productivity and pay for typical workers across sectors, and I couldn't figure out why.

So rather than just do a Baomol's cost review, this is the attempt to try and figure out an answer to the wage question and see if that links up the whole thesis.

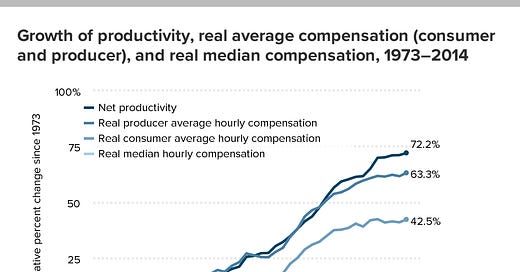

I came across this in rereading an older paper that had somehow slipped by my Google scholar bookmarks. It's called Understanding the Historic Divergence Between Productivity and a Typical Worker’s Pay Why It Matters and Why It’s Real by Josh Bivens and Lawrence Mishel from September 2, 2015. The money chart below:

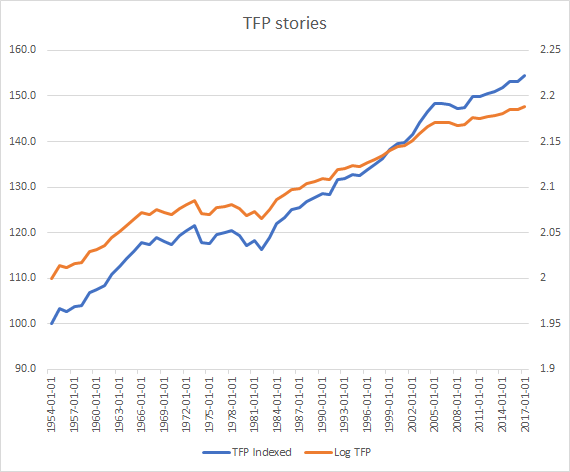

Major surprise (to me) was once again seeing how clear the TFP trend was. America had a lost decade in the 70s - but it had Nixon, the Vietnam war, the oil crisis, the Iranian revolution, the Israel wars, and the rise of disco. So perhaps it's not all that surprising that things went pear shaped and stayed that way for a decade or so.

Apart from around a decade in the 1970s it's been growing steadily throughout the past several decades.

And just to make sure it's not just the US doing some shady stuff, shall we take a look at the TFP figures in the socialist utopia that is France?

Yup, seems like it's something systemic indeed.

This is sort of a big concern for everyone. After all, if we're going through a major economic upheaval in terms of how people feel in their jobs, that changes the whole equation. It impacts politics. It impacts lifestyle considerations. It impacts the entire society.

There's an annoyingly pervasive argument that this is because of the trends of globalisation and technology. Though the starting point of that divergence makes me question that assumption. Were we vociferously globalising in the 70s? Were we pushing technology based efficiency mining by automation in the 80s? Things can have started by another cause and this might be still a contributing factor, that's true. But it still doesn't explain the bulk of the problem.

Rumour has it this is how guillotine construction gets its start. So let's try figure out why this might be the case.

Looking at a few potential causes

Let’s dive in and take a look at a few of the potential causes here.

More women in the workplace caused downward pressure on wages for everyone

Women had started working pretty much from the advent of WW I, when more workforce participation started becoming necessary, rather than an option. By WW II, this expanded from just the unmarried women to married white women as well.

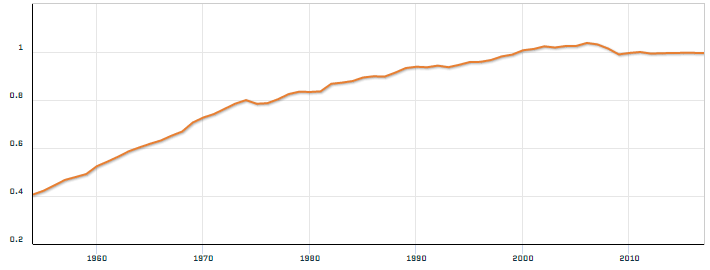

By the 1960s this became the beginning of a trend, hitting c.45% in terms of labour force participation rate and that seems to have provided the impetus for this particular argument to come to the fore.

The 1960s and ‘70s were a transformative time for women and work. Thanks to a host of new and amended laws (the 1963 Equal Pay Act, 1964 Civil Rights Act, 1972 Title IX of the Education Amendments, and 1979 Pregnancy Discrimination Act) ... In addition, women were now able to apply for higher paying jobs that once were available only to men, continue working when they became pregnant, and even attend professional schools. This resulted in a substantial increase in the percentage of women, particularly those with children, working outside of the home: from 27% in 1960 to 54% in 1980 to 70% in 2012.

Let's start by playing devil's advocate. This seems counter to the paper by Amanda Weinstein who suggests that women entering the workforce has been an unqualified good, and is one of the best ones I saw that argues against the mainstay idea that "more women, more labour supply, less wages". Happily her analysis runs counter to this economic intuition.

This particular analysis went through a few model formulations and it looks sensible. But the cross sectional analyses are aimed at looking at how the variation in women entering the workforce changes the effects. This was tested well by looking at it across time, across states and within states, to keep out those confounding real world issues.

Also the paper looks at high initial labour force participation amongst women leading to subsequent wage growth, and there's a big question amongst immediate substitution effects of increased labour and later on the growth re-emerging for all sorts of reasons.

(also does that cluster of dots make you think, "woah this is complicated" or "let's draw a best fit line"?)

Amanda concludes that a 10% female labour force participation increases the wages for everyone by 5%, while the opposite is true at only 3%. If women are replacing unproductive men and increasing overall productivity, but men are outcompeting men by causing supply side shenanigans, then the variation in jobs taken has to be part of the equation.

And it makes sense that women would be more productive than men in general, in the starting stages, because only the most productive women would've been brave enough to push the societal boundaries and start taking on jobs.

To me this still feels like a combination of women taking on different jobs and their starting point in the workforce participation race makes the difference.

Daron Acemoglu, he of the Why Nations Fail fame, and David Author wrote a paper called Women, War and Wages where he argues the opposite case by looking at similar datasets. Post WW II, more women entered the workforce, the shift remained permanent in most places, and the natural experiments of variation in female workforce participation was shown for reduce wages for all.

This held especially for the places where supply increased most, which was the lower wage jobs where the skill delta was the least. However this also runs counter to the argument in the same paper that the marginal female participants were of the highly educated variety. Whether they still ended up going for lower wage lower skill jobs is arguable, though the biggest difference seems to have come in the "high school equivalent" range, lending some credence to this idea.

By this argument the continuing delta in wage depression is perhaps a story of women slowly moving up the skill ladder through better education and training creating a wage depression ladder even for the higher skilled jobs. And why didn't this then create a rebound effect for the lower skilled jobs? Because they moved elsewhere through the usual bugbears of globalisation and automation during this ladder climbing exercise.

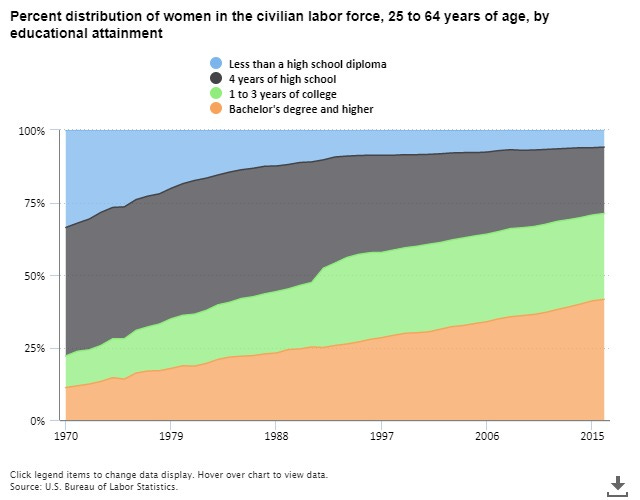

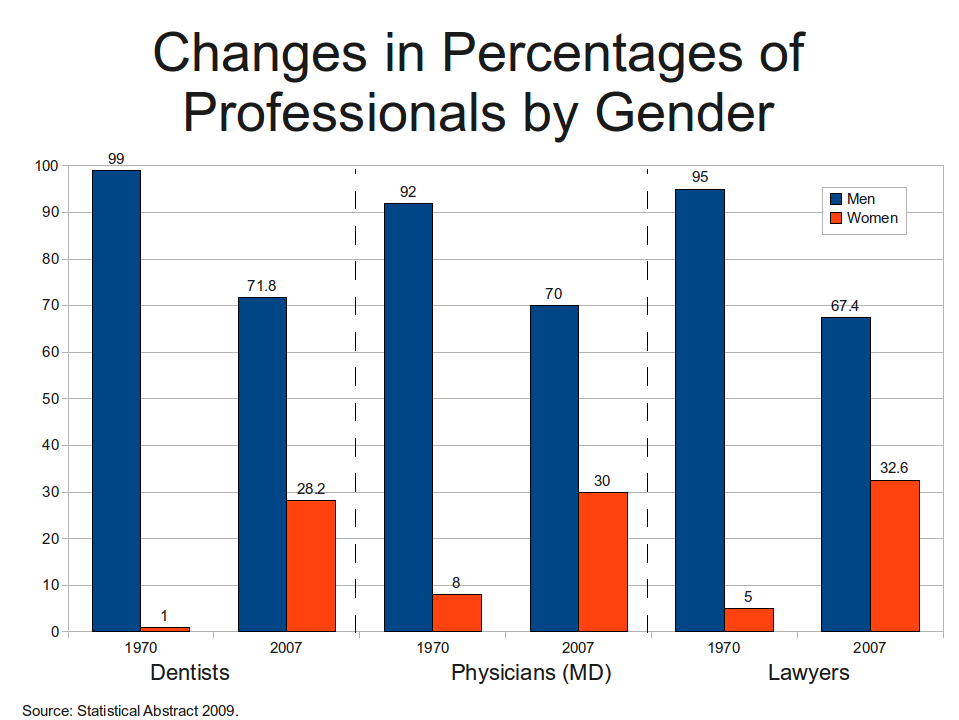

The increase in women in professions that are definitively not "low skilled" (as below from Statistical Abstract, 2009) provides some more circumstantial proof.

As dangerous as timeframe eyeball comparisons are, the timing matches and makes sense. Of course this probably only means an added 5% credence to the conclusion for me. Still, it's suggestive.

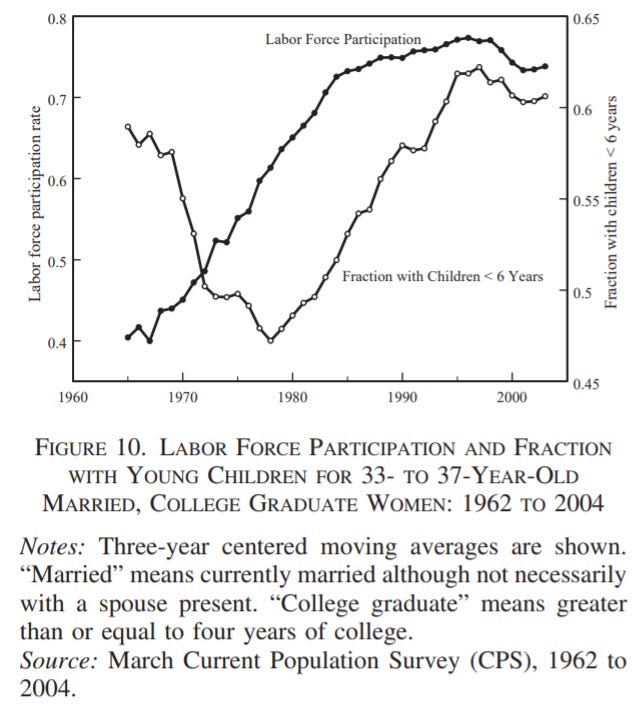

None of these graphs have a clear inflection point in 1970s, but that's not surprising since the world is slightly more complicated than a Stats 101 course. If you absolutely must see a graph though, here you go.

Please don't extrapolate too much from this one data point. You're welcome.

Average worker productivity has actually stagnated, what we're seeing is the effect of a few super-duper productive people

The argument here is easier in some ways to debunk. All you need to do is to go to the nearest McDonald's and see if the cashiers and workers have better technology available than before. And they do. So it could be that while their available capital has increased steadily, the workers have gotten much worse to compensate.

And I refuse to believe that flipping and selling burgers is somehow a civilisation specific and important skill that we've now lost.

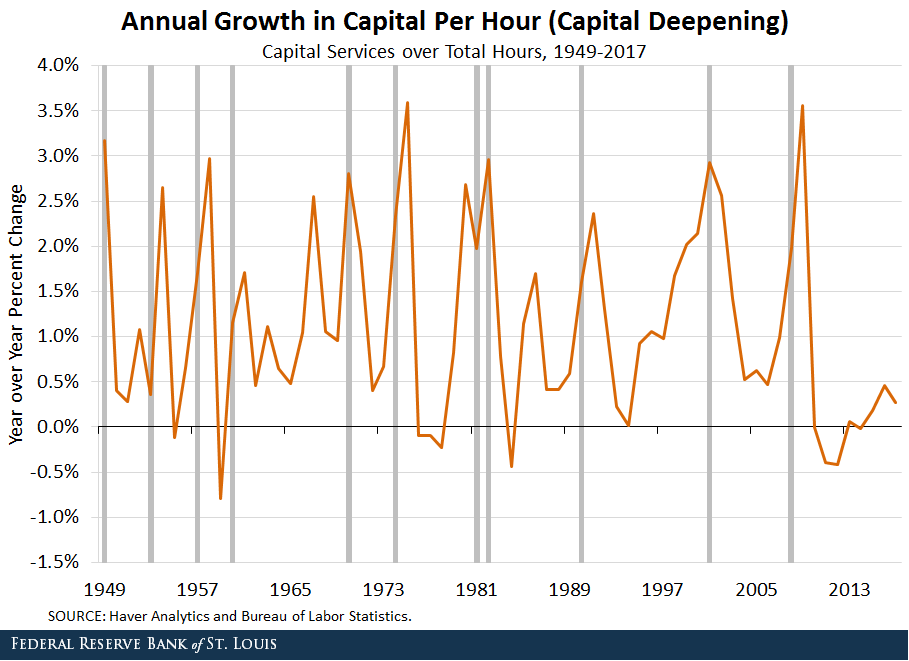

However unlike the authors I don't think saying that capital deepening has affected all sectors let's us get away from at least some of the dynamics. For instance, in banking we used to need multiple back office employees to reconcile the books. Today it requires zero. (Well not zero but substantially less.) So the jobs that needed doing has shifted due to capital deepening. And that will cause delta in wage growth.

For instance, the St Louis Fed chart on capital deepening shows that it's had a fluctuating, but growing, trend over the past century.

In our example we only need a couple staff to make sure the figures input are right. So they're more productive. But a few have lost their jobs. They're unproductive. There's also the new IT guy who, let's assume, is super productive. The net might be flat, but the distribution is varied.

And a variation in distribution causes a variation in wages and inequality. The remaining tellers are scared to ask for a raise - they can be fired and replaced. The IT guy can and does get a raise. Net effect on the wage chart, again mixed.

So this is an instance where the average worker productivity has definitely increased, but the distribution of those workers themselves has changed. And that reduces the negotiating power, at least until there's a generational shift and the skillset distribution also changes.

There's no problem, it's just everyone incorporating as a "pass through entity"

For one thing I'm not sure this applies to anyone much below, say, the 90th percentile in income.

From the paper The Rise of Pass-Throughs and the Decline of the Labor Share by Matthew Smith, Eric Zwick et al.

This paper studies the coevolution in the United States of the fall in the corporate sector labor share and the rise of the share of business activity organized in tax-preferred, pass-through form. We find that reallocating activity to the form it wouldhave taken prior to the Tax Reform Act of 1986 accounts for 30% of the decline inthe corporate sector labor share between 1978 and 2017. Our adjustments attribute 15% of the decline to labor income recharacterized as profits among S-corporations within the corporate sector. The remaining 15% is due to the rise in labor-intensive business activity that elects partnership rather than corporate form. In our adjusted series, the labor share decline in the United States is primarily a manufacturing sector phenomenon that was offset—fully until 2000 and partly since then—by the rise of services.

From the Brookings analysis, it does look like there's been a movement in the positive direction. But even under the most optimistic impression, this only makes up for the shortfall in the higher percentiles.

An overwhelming share of pass-through income is earned by those at the very top of the income scale. In fact, about 70 percent of partnership income accrues to the top 1 percent, compared to 44 percent of corporate dividends

Now there's a clear argument that this is part of the problem at the top levels. But I don't think the income percentiles at 50 and below are all running their own Restaurant Worker LLC to fleece the taxman.

So I'm going to put this in the "it's an effect, but mostly for the rich, and it doesn't matter that much anyway" pile.

Jobs stopped being easier to get as there were less jobs available per employee

Definitely doesn't seem to be the case that there were lesser jobs on the top line here.

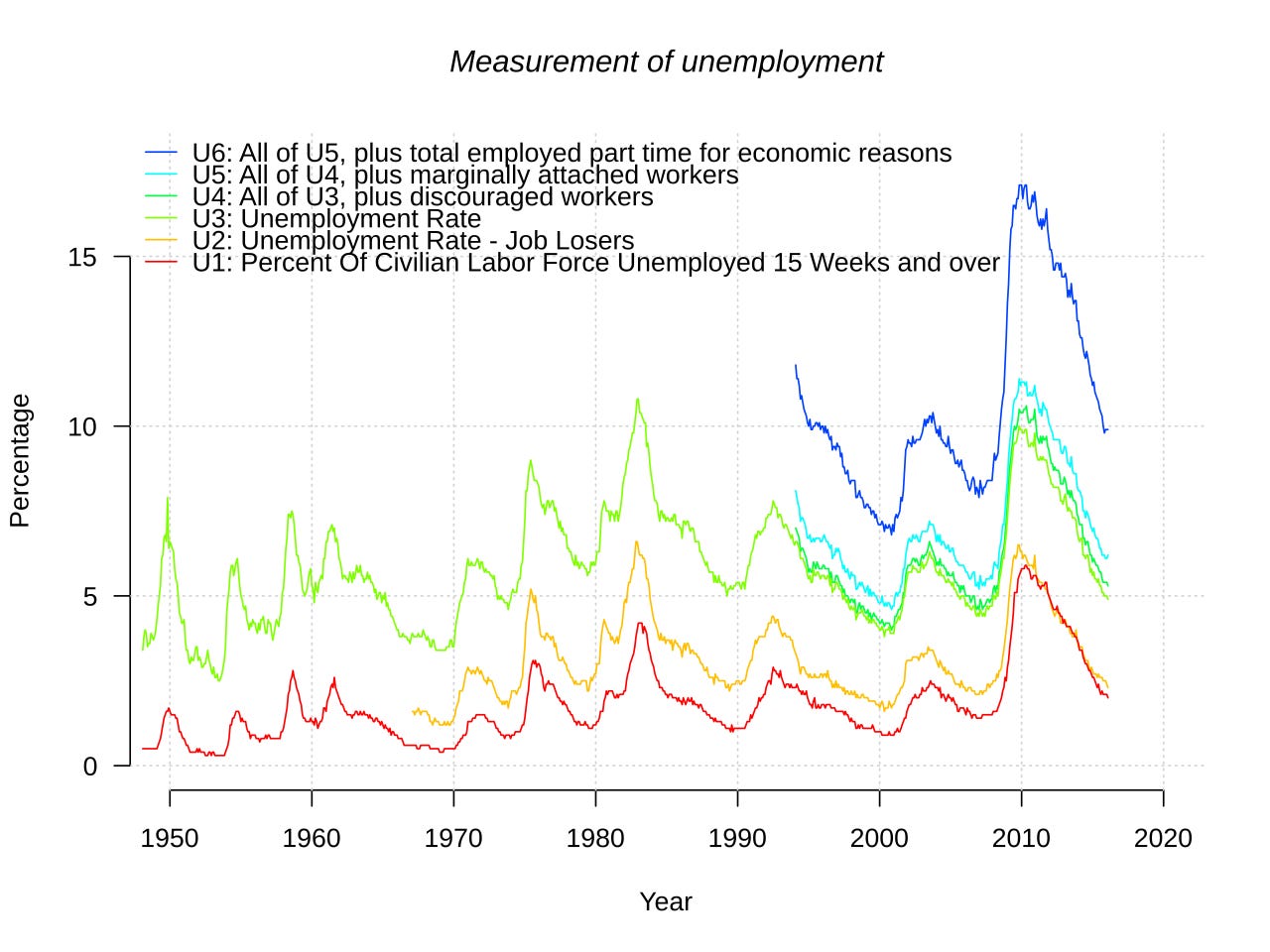

Was there a crazy spike in unemployment, as that could indicate that the number of employees per job would've spiked. There definitely has been a few larger spikes post 1970, and if you squint your eyes you can see slightly increasing rates of unemployment rates, but I'm loath to draw conclusions from one barely moving chart, especially when there are demographic effects to consider.

It's of course still a logical possibility that everyone is applying for more jobs even if they're somehow coming back to only doing one. In that scenario we'd all be better off if everyone just started applying to only 50% of the jobs they were doing before. But that feels like a game theoretic equilibrium we can only reach if there's an Application Czar.

Are there less variety of jobs available which increases fragmentation and reduced labour market power also doesn't seem true as an alternative.

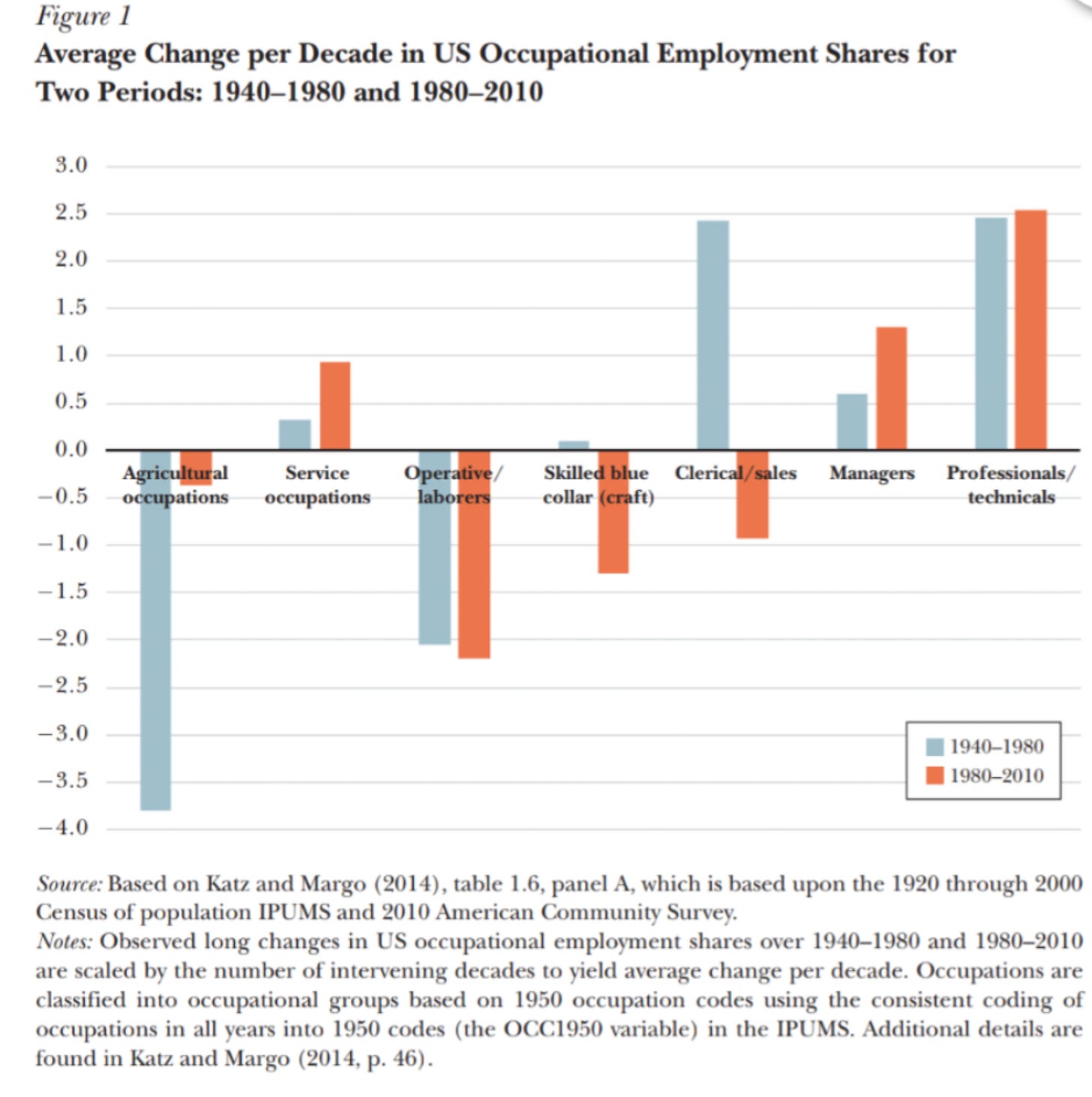

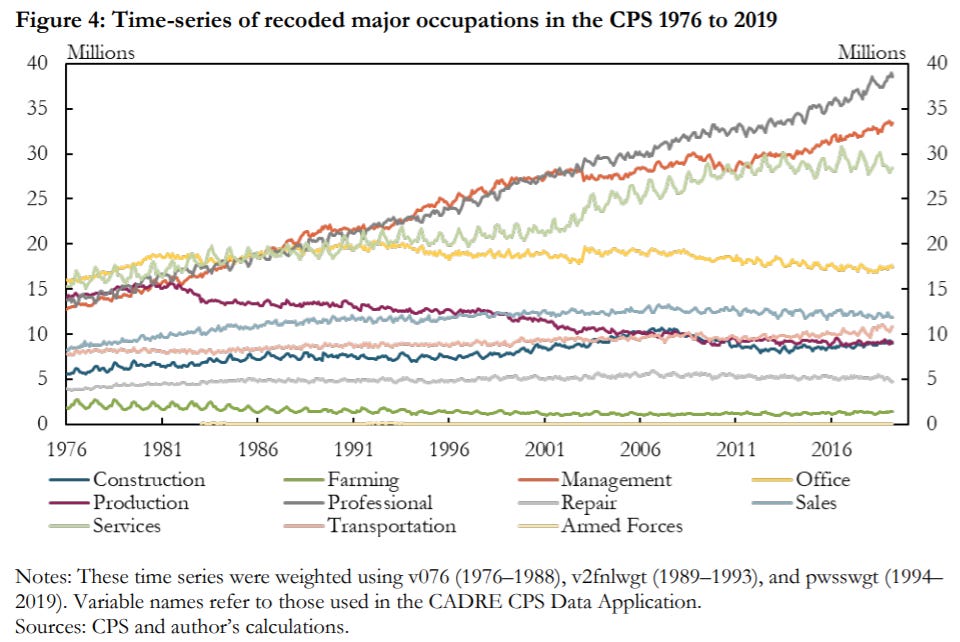

Let's see how the occupations themselves changed over time.

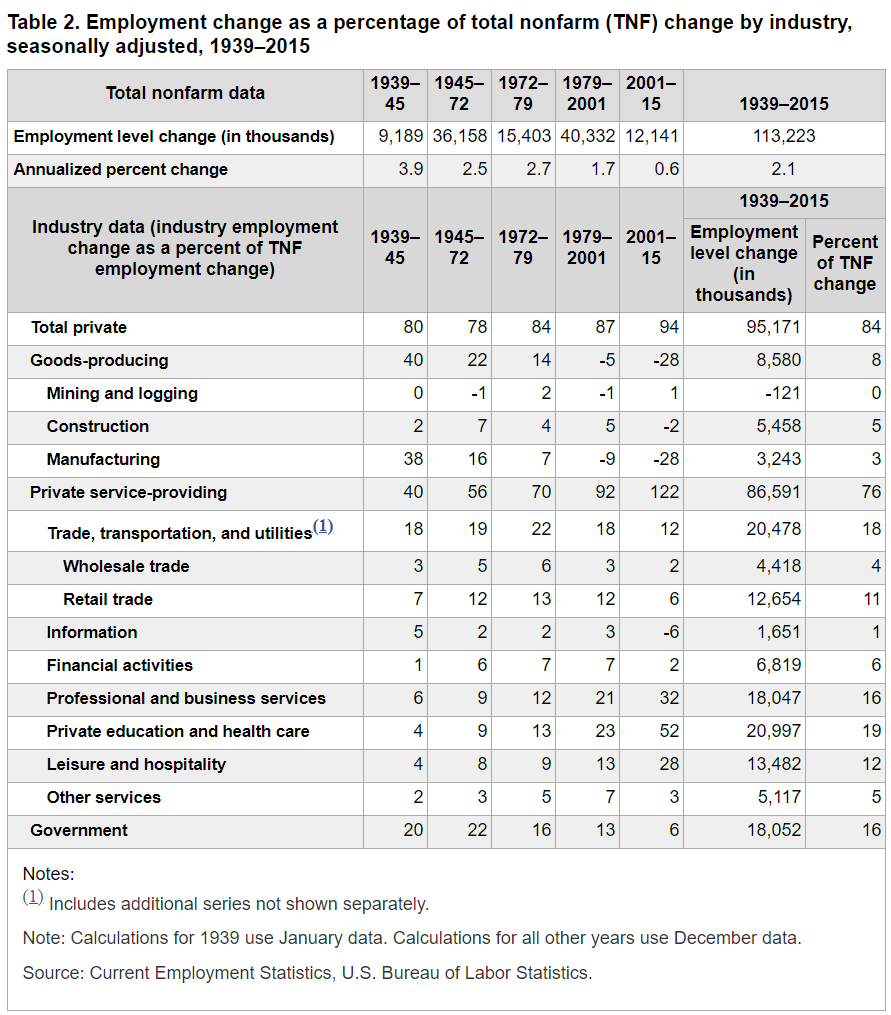

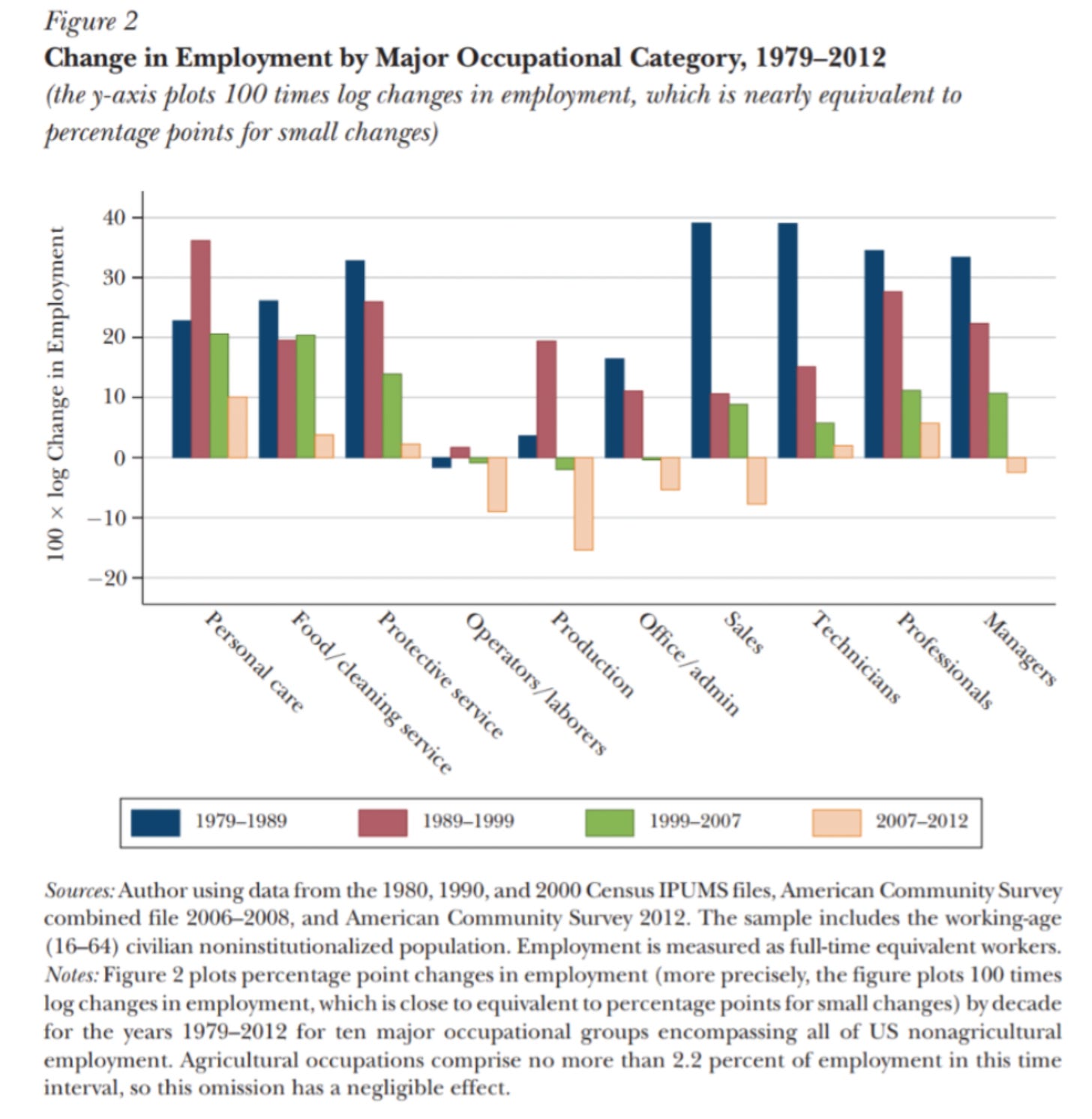

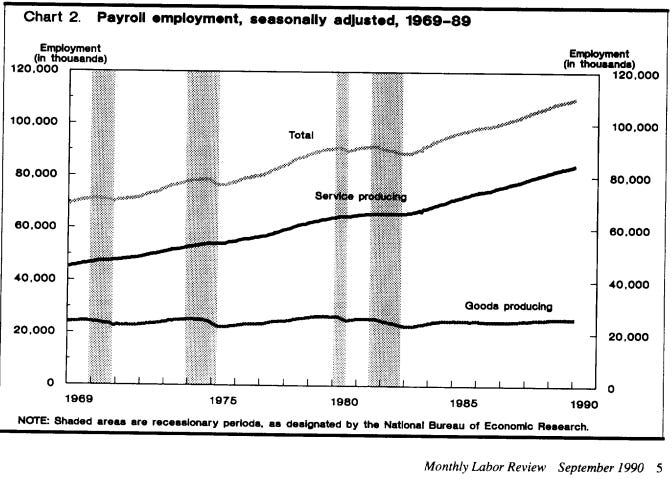

And how did the actual employment itself change, in numbers?

The changes show that the growth rates pretty much were the same or lower for most job types. That's itself interesting, since it means that the birth and scaling of new technologies had primarily a substitution effect amongst employees.

Was there more competition for same jobs as markets lost boundaries (locality for instance) - which made larger markets for each job segment? Most likely. Let's imagine an idyllic scenario in the 1970s when you would be going and searching for a job in New York as an ad exec. There's you and two others. There's more than two companies. You're all happy wearing thousand dollar suits and emulating Don Draper.

While look at the situation now, you're one amongst hundreds. Just from Harvard Business School there are a 1000 MBAs venturing out into the world every year. Add up every elite school and you've pretty much ensured the supply of wannabe executives is endless.

Parenthetically this also explains why there's grade inflation. If you have only 10 candidates for a job, then they don't need to all have 4.0 GPAs. If you have a 100, then GPA is an easier way to at least screen out a bunch of them.

But are we seriously considering that there are less types of jobs these days compared to others?

I also wanted to find an estimate of "employees per jobs advertised" to get a sense of whether people are indeed applying for way more jobs today and making everything much more competitive, but wasn't able to get much data here. If anyone has a view would love it!

Demographics and a change in natural birth and death of industries changes wage distribution

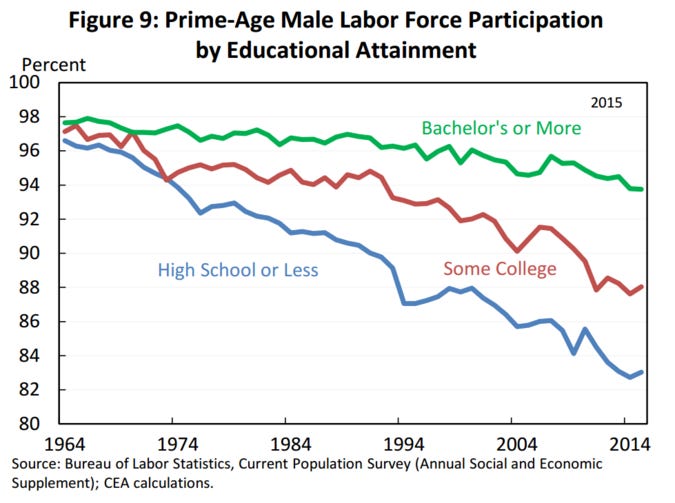

So a few things have happened in the past 70 years. The labour force is aging, especially once you cut it by race. The cut by educational attainment is ever sharper, with those who have less education essentially locked out of the economy pretty much.

The takeaway here is that if the workforce is aging, and if the industry mix is simultaneously shifting, then the ability of the workforce to flex and enter the "growing industry" from the "falling industry" will be minimal. Which means a lot of them will get locked into a wage spiral since there just isn't enough demand for their jobs.

There's also the shift in industries themselves over time, as can be seen in the CPS industry recoding data, broadly showing how the Professional, Services and Management jobs have had the most significant changes. This also stands up to intuition, which is a nice add-on, and also shows why flexibility in moving into or out of these jobs isn't as easy as the others where skill levels might have been more fungible. Most importantly it shows a polarisation amongst the occupational types and styles that have emerged.

For instance, consider the proverbial coal miner and the software engineer. If coal is declining, as it is, and software is growing, as it is, there's very limited ability for him to switch from one to the other. If you're a 21 year old coal miner maybe this wasn't as big a problem. But when you're a 40 year old coal miner, you're not really going to be kombucha-ready in a few short lessons. So you're stuck.

Can't coal miners just ask for more money since their labour is scarce? Not really, since 1) it's not scarce enough, and 2) they're still replaceable as coal itself is declining.

Non wage compensation grew like crazy and is actually hidden in the data

From the original study, showing they were smarter than the average bear:

Nonwage benefits as a share of total compensation rose much more rapidly (from 7.2 percent to 18.3 percent) between 1947 and 1979 than thereafter. So, again, if the question at hand is why hourly pay for typical workers tracked economy-wide productivity for decades after World War II and then began diverging in the late 1970s, rising nonwage benefits really cannot be the answer. Nevertheless, we use measures of compensation, including all employer-provided benefits along with wages, in our measurement of “pay.” We do this by taking measures of wages and inflating them by the ratio of compensation to wages that holds economy-wide to convert them to a measure of compensation.

The other form of this is to argue that it's just because we're getting part of the compensation paid in equity.

But there's no way to make that case rationally without seeing like a dolt who's delusional about what the other 99% lives like, so that's left as an exercise to the reader.

General statistical tomfoolery causes all the confusion

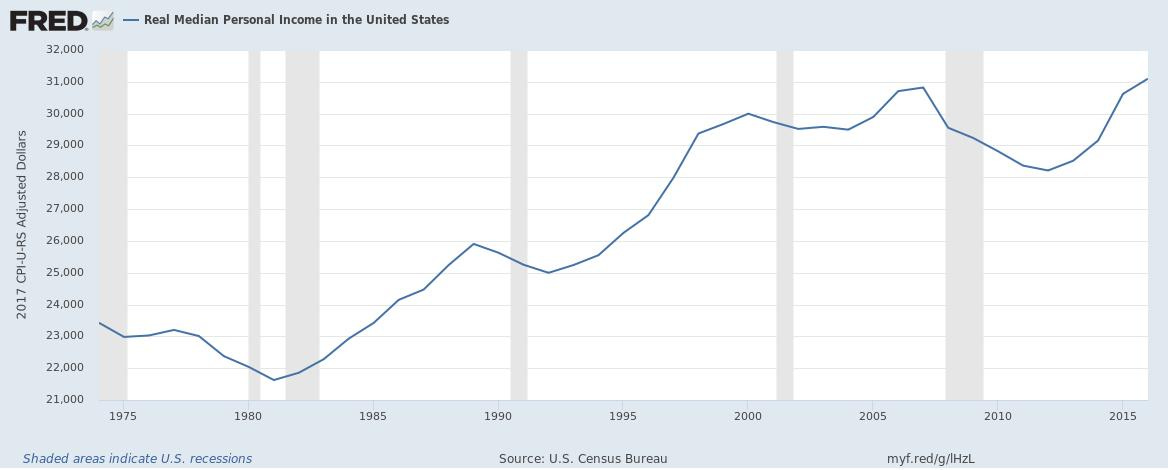

For example the data from Fred shows something different in income trends:

For typical workers’ pay, there are really only two deflators that one could make a serious argument for using: the CPI-U-RS (a variant of the standard consumer price index [CPI-U] from the BLS that adjusts for past problems in measuring housing costs) and the price deflator for personal consumption expenditures (PCE) from the BEA.

From the article again:

The fact that the CPI-U-RS has grown faster than the IPD in recent decades simply means that prices of goods and services consumed by households have risen more rapidly than a basket of output in the IPD (a basket that includes these consumption items as well as goods and services purchased by businesses and governments).

This doesn't seem like a statistical problem as much as a reality problem.

One way to test is for us to check if we look at the disposable income charts if that also shows a big drop-off, or whether the growth there makes sense.

And, lo and behold, the vaunted reduction in disposable income rises again.

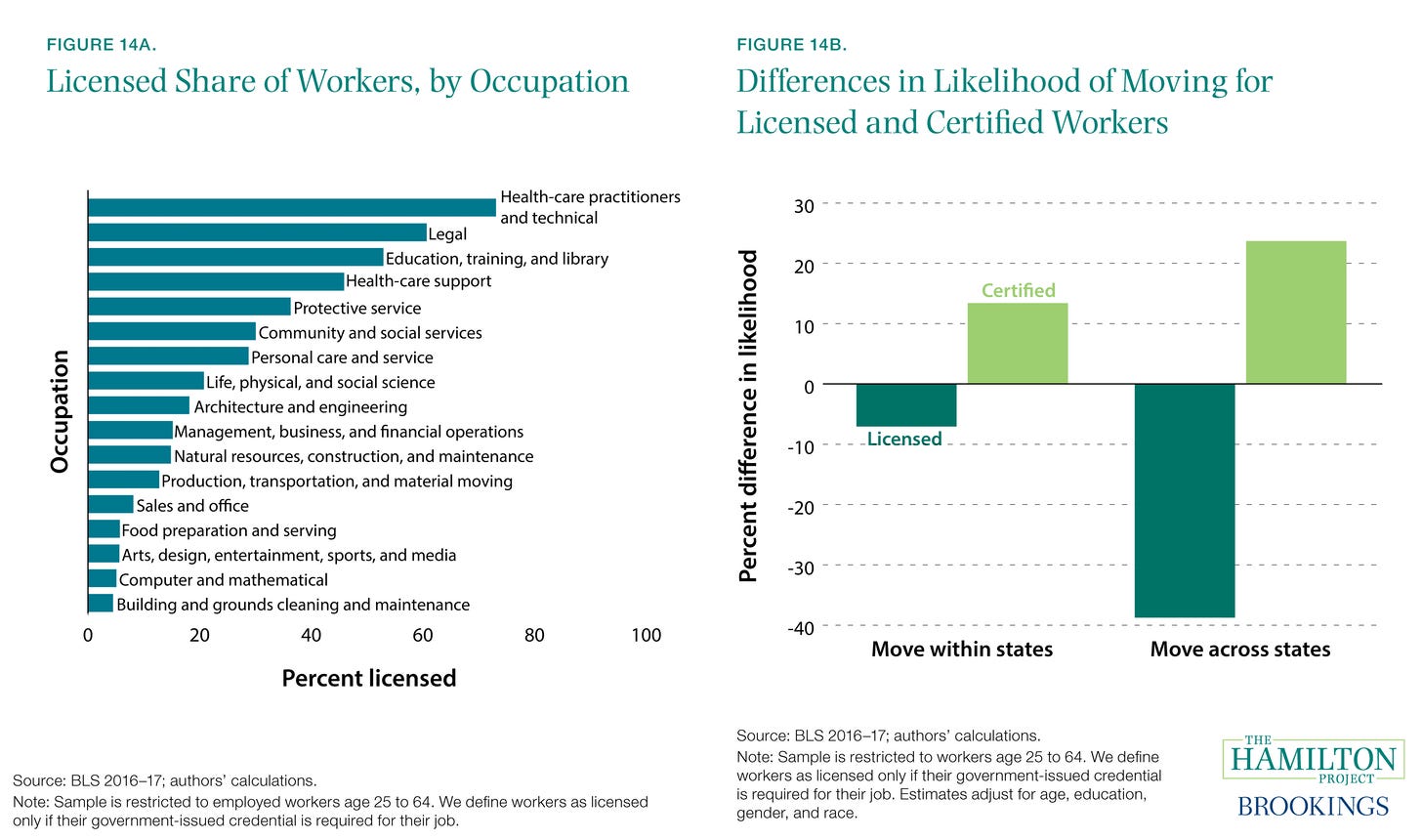

More complex HR gatekeeping and increasing "standards" like education and regulation

Rise of the licensing industry has spread through the occupations, and effectively strangled a large enough portion of the workforce in expensive requirements and reducing their flexibility.

The larger part of the licensing seems to have happened in industries which have also grown and systematised, like healthcare and law, and while it has had impact on much less critical areas like "Personal care and service" and "Life, physical and social science", it has to be severe indeed to stop wage growth in its tracks. And that's a big assumption.

If this is the key trend that is said to have driven the wage reduction overall, then we also have to explain why all the licensed jobs at least don't have a moat around them, with the hairdressers and nurses and dental assistants having far-better-than-median lives. Yet that doesn't seem to be the case!

There's also the opposite result being reported by people who studied labour market efficiency in matching workers and jobs, with the anguish that this is getting harder as the workers are getting less credentialled. While this might seem like the "get off my lawn" type of complaint, bear in mind it would also be true if in the 1950s only the best students went to university, while in the 80s a larger proportion of the populace did, pulling the average down! Like this paper by Daniel Mitchell argues:

There is evidence, based on declines in SAT scores and other measures of school achievement, that quality of new entrants to the work force did decline after the mid-1960s, although there was some reversal of this trend in the 1980s. The popular press has often carried reports of declining discipline at the high school level

Unions got busted

If we could all do some form of collective bargaining then of course we could push for higher wages. This is a time honoured labour market negotiation tactic, and is one that is still being argued. One reason why Google unionised recently, after a decade plus of fighting the trend. The same is likely to come for Amazon and others.

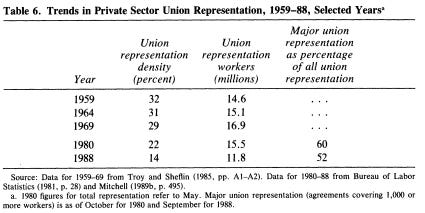

Daniel Mitchell has something to say here again.

Yes, reduction in union representation did seem to coincide with reduction in wages. But it's also true that unionisation could have had negative impacts in the overall supply side. Yet that's not a question with an easy answer. This remains a point to be investigated and the correlation here could be causation.

One point though is that industries like healthcare, education and parts of manufacturing have had unions through the times, but none of them have seen much positive benefit of such unionisation in terms of wage increases. It seems the story is slightly more complex than just collective bargaining.

What is a job - there was an increase in temporary and part-time work that skews all results

From the amazing NYTimes article that was luckily obsessed by looking at this history.

For example, in 1971 the recently renamed Kelly Services ran a series of ads in The Office, a human resources journal, promoting the “Never-Never Girl,” who, the company claimed: “Never takes a vacation or holiday. Never asks for a raise. Never costs you a dime for slack time. (When the workload drops, you drop her.) Never has a cold, slipped disc or loose tooth. (Not on your time anyway!) Never costs you for unemployment taxes and Social Security payments. (None of the paperwork, either!) Never costs you for fringe benefits. (They add up to 30% of every payroll dollar.) Never fails to please. (If your Kelly Girl employee doesn’t work out, you don’t pay.)”

Becoming lean and mean had never been easier, and thousands of companies began to go the temping route, especially during the deep economic recessions of the 1970s. Temporary employment skyrocketed from 185,000 temps a day to over 400,000 in 1980 — the same number employed each year in 1963. Nor did the numbers slow when good times returned: even through the economic boom of the ’90s, temporary employment grew rapidly, from less than 1 million workers a day to nearly 3 million by 2000.

Similarly, let's look at the article already referenced, from Richard T Ely lecture by Claudia Goldin about women in the workplace.

With the creation of scheduled part-time work in the 1940s and its enormous diffusion in the 1950s, the substitution effect became larger. Reinforcing factors include the almost complete diffusion of modern, electric household technologies, such as the refrigerator and the washing machine, and the previous diffusion of basic facilities such as electricity, running water, and the flush toilet.

It unequivocally says how increased flexibility started becoming the norm, and the substitution effect of part-time work is high.

This clearly moved the wage needle sideways. Once things became part of the efficiency creation mode, and part of the workforce starts going the temporary route, the knock on effects start to kick in. Wage discussions move at the margins, and as the margins get pushed down that would create an overall effect.

Chalk this one down for "yes there's an effect, but unclear how big and how persistent".

Jobs stopped being easier to get as there were more applicants per job

Suppose there are 100 candidates for 100 jobs, split into 10 companies. Each company gets 10 applicants, they need to hire them. The negotiating power is simple. Now imagine that all 100 start applying for all 100 jobs. Now the power delta has changed. Each company has tons of implicit power to play the applicants against each other. It's an equilibrium solution that doesn't help matters much!

This one also turns out to be much harder to assess historically. But let's look at a few anecdotal pieces of data that's out recently.

BBC:

With university degrees, years in employment and youth on their side, Nick and Emily McKerrell are examples of just how difficult the jobs market has become. Not only are they struggling to find work, few employers even bother to reply to their job applications.

In the worse hit areas of the UK, 40-plus unemployed people are chasing every job.

Dire state of UK jobs market revealed as 4,228 people apply for one entry-level vacancy

98% of job seekers are eliminated at the initial resume screening and only the “Top 2%” of candidates make it to the interview”, says Robert Meier, President of Job Market Experts.

What was going on in 2010?

Graduates warned of record 70 applicants for every job

Now let's cast our eyes back to the misty land of the 1980s for what recruiting was like back then:

If you knew the actual job needs in detail and the hiring manager personally, you only needed to present 2-3 strong candidates to make a placement. You’d normally only need to talk with 8-10 reasonably strong prospects to wind up with 2-3 strong candidates. Half of these strong candidates were typically referrals from the group of prospects. It only took 4-5 days of phone calls to generate 2-3 strong candidates. This dropped to 2-3 days once you developed a deep network of top prospects.

And the result?

With the birth of the Internet and job boards in the 1990s and the emergence of ATS around 2000, the high-touch, “quality is #1” approach was losing favor. Companies thought they could “win the war for talent” using technology to reduce the cost per hire.

And the direct result here is shown in this article and these research articles - one, two, three, four. There's clear trends that employment mainly seemed to increase in some of the services sectors, while goods producing employment stagnated, simultaneous to how the productivity in goods producing industries rose and services stagnated. There's a clear supply glut answer to the overreliance here as well, one that's undertold.

And what was going on in 1970, the end of the golden age?

People still hit the pavement—literally walked around to offices—to hand out resumes. Job ads directed job seekers to inquire in person or by phone.

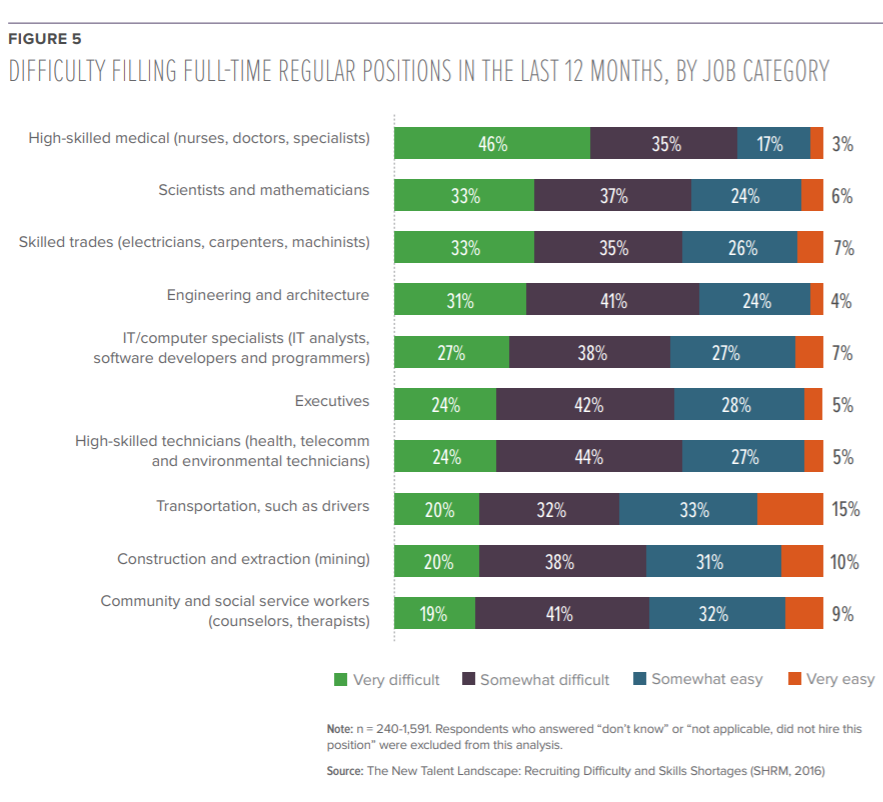

How exactly has this number trended over time is unclear, but it's at least clear that there's been a decline between 1980 and today, where the number of applicants have skyrocketed! To slightly complicate matters there is also clear indication that the skill disparity has made some jobs, usually the higher skilled ones, much harder to hire for vs others.

While at the highly skilled end there seems to be more power with labour, this declines sharply pretty quickly. And if supply of talent has risen so steadily, can the price help but not rise?

Other usual contenders - globalisation and automation

This has been written about a lot, so I'm not going to delve into either factor in much detail. And analysed in hundreds of different ways. And it's something that really only came to fore in the 1990s onwards. With all of that it's not one that I'm going to spend a huge amount of time on. So just two snippets below, then we move on.

Re globalisation, this is also a story with multiple levers of impact. For instance, quoting from "Why are there still jobs", a paper by David Autor

... there are the employment dislocations in the US labor market brought about by rapid globalization, particularly the sharp rise of import penetration from China following its accession to the World Trade Organization in 2001 (Autor, Dorn, and Hanson 2013; Pierce and Schott 2012; Acemoglu, Autor, Dorn, Hanson, and Price forthcoming). China’s rapid rise to a premier manufacturing exporter had far-reaching impacts on US workers, reducing employment in directly import-competing US manufacturing industries and depressing labor demand in both manufacturing and nonmanufacturing sectors that served as upstream suppliers to these industries.

Re automation, this hits multiple skill levels. For instance, to quote from the same paper:

...the highest ranked occupation to lose employment share during the 1980s lay at approximately the 45th percentile of the skill distribution. In the final two subperiods, this rank rose still further to above the 75th percentile—suggesting that the locus of displaced middle-skill employment is moving into higher-skilled territories.

In conclusion, yes both of these are determinants of how the supply side of the labour equation changes dramatically. Yes they impact some workers the most - the medium to medium-high skilled workers.

Conclusion

One major takeaway I had looking at this is that I respect the hell out of others who look at this professionally because it's so insanely convoluted for good reasons and also for the most annoying of reasons - none of the data is in what I'd consider a halfway decent shape. I almost want to turn everything over to Facebook and tell them to make it usable.

Second thing is that now I understand why anyone gets to tell anyone else anything based on data. It's (as should be obvious from the sheer number of variables) all over the shop!

If I wanted to make the data argue for the case that Martians visited us in 1970 and took our wages, the data could support that too. And all the fancy theoretical analysis (read lots of really smart adjustments and then running correlations) that is done piecemeal in individual papers all fall apart as soon as you add one or two variables to reality. If this is what labour economists spend their days doing, someone should really start a Patreon so they can buy even more alcohol.

The third thing is a better sense of absolutely how many things actually happened, several relating to each other, to make this wage disparity come about. My quick and dirty summary:

Employee side

More demand from increased workforce entry of women - starting with the medium skill stuff like clerks and stenographers and moving up the skill ladder

The educational status of employees changed over time as most employees have higher levels of education

The employees aged over time as well, with that demographic change reducing flexibility to move around jobs, and might even end up becoming underemployed

Globalisation helps increase the labour force for most jobs far more than before since geographic restrictions no longer apply

People are applying for tons more jobs than before, and are creating a competitive market where one shouldn't exist

Employer side

The job market flexed away from being pretty good for middle skilled workers to being decent for high skilled workers

Education is not keeping pace with job requirements so people are badly qualified for the jobs that do exist - people do degrees as a shortcut to management jobs though that train left half century ago

Employers are getting larger and this means that they have an increased ability to negotiate wages that are more favourable to themselves

With increasing automation, jobs can be "divided up" better, increasing possibility for automation, outsourcing and offshoring. This also makes jobs more competitive, since the skills needed get reduced

Automation makes demand for jobs a) less in aggregate, and b) more polarised where the higher skilled jobs increase in demand and pay (hello data scientists) than others (hello bank cashiers)

Market side

The market has shifted from more artisanal matching to more sophisticated spot market making, increasing efficiency and also liquidity

Jobs have changed in their very essence - from permanent paychecks to an increase in temporary or contract jobs

More middlemen in the job matching industry meant that the seeming increase in market efficiency was tempered with less smarter linkages

The types of jobs also shifted, from manufacturing to services, though the impact of this is not particularly clear

Overall the impact might have been that there was better negotiation ability for salaries as you get multiple offers in some jobs at least, while rest of the comparable ones get a nice Baomol's cost effect impact. When parts of the economy get major wage pressures put on it, that translates to other segments too.

For instance, with the diploma inflation, we have much larger numbers of college graduates today. They're all eligible for certain jobs, and apply with abandon (since getting one is so damn hard). What this means is that our inability to match talent to job has created the perception of an incredibly competitive job environment. And when that happens the pressure on wages only goes in one direction.

So even if a large number of the issues were real (and no they're not to anywhere enough extent to change things) you can also ask if the subjective experience of jobseekers have changed. And here I give you my favourite snippet from a forum.

I discussed this with my mum at one point and she said when she left school she could become a Receptionist, Secretary etc pretty easily, her first job was admin in the local council. Nowadays I haven't even got to Interview stage regarding my applications for (the few) Receptionist vacancies, depressing.

And if you're confused as to what happiness looks like, maybe it's something like the right side of this chart.

I don't think there's a decent way to get everyone to that happy place. That would be silly. But we can but dream.

Let's assume a mythical economy with 10 people. Each person has a combination of 10 factors, each at a fraction from 0 to 1. There are 10 jobs in this economy, and each person with the highest score in each factor is the ideal employee.

Let's assume also that the employers aren't great at discerning who's ideal, but can only discern a particular level of skill and potential. So anyone who falls above that threshold would fall into the "competitive" pool, and can theoretically go for the same job.

As time goes on, let's say the pool shifts. They get educated in college, theoretically changing their skill composition and making more of them competitive for more jobs.

Model here - https://docs.google.com/spreadsheets/d/1DoH8TVjSLx8x9Dcdb--tivGmRrDrrSU3G0ghHfXWJJ4/edit?usp=sharing

As is easily visible here, if the "skill level - job" delta narrows, more people fall into the potentially competitive situations. Bear in mind, in this model the number of jobs haven't increased. What's changed is that the supply-demand balance of jobs has shifted with the demand becoming higher.

Can the employees also play the same game in reverse, where they have multiple job offers in hand too, and therefore gain negotiating power? Interestingly enough this has been my observation of jobs in my circle. Most professionals have multiple options to jump jobs and several do. So there's still a fair amount of stickiness that comes from this scenario. Whereas theoretically the ability to jump jobs exists, practically for most employment options that aren't data scientists or the equivalent, the power still remains with the employers.

This also holds true because not all jobs come to the market at the same time and therefore you won't get an easy market-clearing price.

And in any case, the anecdotal evidence all seems against it too. There just doesn't seem to be too many stories going around about how choosing amongst these multiple job offers is so hard!

What can we take away from all this? My (highly speculative) conclusions:

There's been a delta in terms of demand-supply gap for most jobs since the 70s. It probably happened for several of them even before, but the trend's been pronounced thereafter. This happened because of multiple reasons, incl higher education rates meaning more applicants per job for the median jobs creating downward pressures pretty much everywhere except for the truly irreplaceable genius jobs, entrance of women into the workforce, and yes, the entrance of automation and offshoring of previously extant jobs

Higher degrees of specialisation seems to help in part, by reducing the supply-demand dynamic, but it's only applicable to a very small proportion of job-seekers, and mostly at the top.

Higher diversification of job types might help as well, though that also has issues. If you imagine the jobs you can get as a pyramid (which is incorrect, but go with me), then even if there's more diversified job types, the fact that enough people will try for other types of jobs lower down the pyramid would create the same dynamic again.

As far as I can see, the only way out is to help create better talent-job matching. I think even the anti-immigrant sentiment, for instance, is a fallout of this issue, that people want less competition within the job market. I have seen probably fifty companies who claim to do better job matching, but even in easily understood professions like software engineering, it's incredibly hard to do well. This is a technocratic utopian dream to keep supply of jobs less elastic, but if wage stagnation is our enemy, then I don't see logically how we can get away from it !

While there's been big shifts also in the areas of statistical tomfoolery these seem like specific technical issue that affects our historical measurements, but not the lived experience.

The demographic shifts have also been instrumental in ensuring that the supply side, especially on the youth side (younger workers starting out) is highly skewed. The increase in types of jobs where they start off means that there's a lot of competition throughout the growth trajectory even within the same job profile.

And the same issue exists re link with productivity as well. While it's easy to get to an angry polemic about how this is the top 1% screwing over the rest, the truth seems more nuanced than that. While there's clearly a part of that, it doesn't seem to have gotten worse than before necessarily. What seems to have happened is more than the top echelons, if they have the power like CEOs, are able to fight against the generic demand-supply situation, and become scarce commodities.

And changes in what a job means (temporary work, now making a comeback as gig work) has made a big impact in jobs at the margins. But here the issue is less about the presence of these types of jobs, but rather the fact that a) several types of jobs can now be sliced and diced and made gig-friendly, and b) with the increasing bargaining power in the hands of employers in several sectors this is now the default mode of work for several jobs. The latter is what shifts the average!

Overall, I found the problem to be much more complex than a simple explanation could suffice. I started believing in the bogeyman of automation and offshoring helping the companies, but left with a more nuanced understanding of how the supply-demand dynamic for jobs has changed dramatically in the last half century.

And while there have been several trends that have coincided to give the current landscape with its lopsided structure. But the fact is that a large part of it came about despite the advances that were made. When individuals made the decision to upskill themselves at the same time as the goods-services productivity was diverging, the resulting wage equilibrium also slipped.

I originally started writing an article called "Education is not the panacea". I feel like I should rename this article to be that, since that's where we've ended up. I still believe in it, but barring a better solution, I'd rather tell you to go read this commencement address first.

What would be interesting would be similar data for the middle income countries. Especially China where there is now complaints regarding jobless growth for the typical white collar wannabe college graduates. The same is in India but there it exists at all levels of society. So the gap between aspirations and what is being on offer is tremendously disparate. I agree with you that better skills, problem and people matching is the only viable solution. These are still serviced by primitive CRUD databases with a front end at best.

By chance did you come across anything mentioning shifts in spending/demand when women were added to the work force? Presumably there should've been a massive increase in the number of consumers as they had more autonomy over their own spending... I assume this would appear in the data somewhere. Offsetting the increase in labor supply conundrum? Also, I would think the shift in family dynamics would impact demand side divorced couples now needing two houses two cars etc etc...