Recently in Baltimore, a container ship ran into the Francis Scott Key bridge pier, and collapsed it. Six people went missing, presumed dead. The Maryland governor called it a global crisis, and the closure of the waterway costs roughly $15 million a day.

And there is the constant question, is this how close we are to catastrophe, that an errant ship can strike any pier and collapse any bridge? Are we all living this close to potential catastrophe?

On the other hand, we had the xz virus incident, which most people outside of computer security geekdom don’t even know happened. A critically important software library, which underpins almost all modern server logins, was infected by a rogue actor, who spent the previous two years working diligently to be seen as a valued community member. And then he did this, decided to hack almost every system that uses Linux.

Under the right circumstances this interference could potentially enable a malicious actor to break sshd authentication and gain unauthorized access to the entire system remotely.

This was discovered by Andres Freund, a Microsoft software engineer, who saw this when he saw a small slowdown in login times, 500 milliseconds, and decided to investigate.

The same question can be applied here too. Are we really okay living this close to a potential catastrophe, that an engineer deciding to investigate a seemingly weird occurrence was all that blocked a historic global hack. Are we really okay living on such thin margins?

The stories about how things went wrong due to this type of surface are in our collective consciousness. Once we notice that our wellbeing is separated from catastrophe by only the flimsy, and sometimes capricious, actions of one person, it naturally creates a lot of worry!

We’re worried about cases like the 2015 Germanwings Flight 9525 crash, where the copilot intentionally crashed the plane, though at any moment there are probably 10,000 planes in the sky.

We like thinking someone’s on the job, creating complex, intricate, resilient structures within which we live safely. The illusion is what we need, and we hate being reminded that’s not true.

That’s why things like terrorism hit so close to our psyche. Terrorism in general has had very small number of perpetrators at its core. The 2001 anthrax attacks in the United States were the action of one person. And the same for Boston marathon bombing or the Nice truck attack.

And we’ve all read the story of Stanislav Petrov, the Soviet officer who disobeyed protocols and reported the supposed launch of intercontinental ballistic missiles from the United States as a false alarm.

So we ask, do we really have to rely on Stanislav Petrovs of the world, of whom there are presumably very few, versus the legions of incompetent or malicious who might well do the worst.

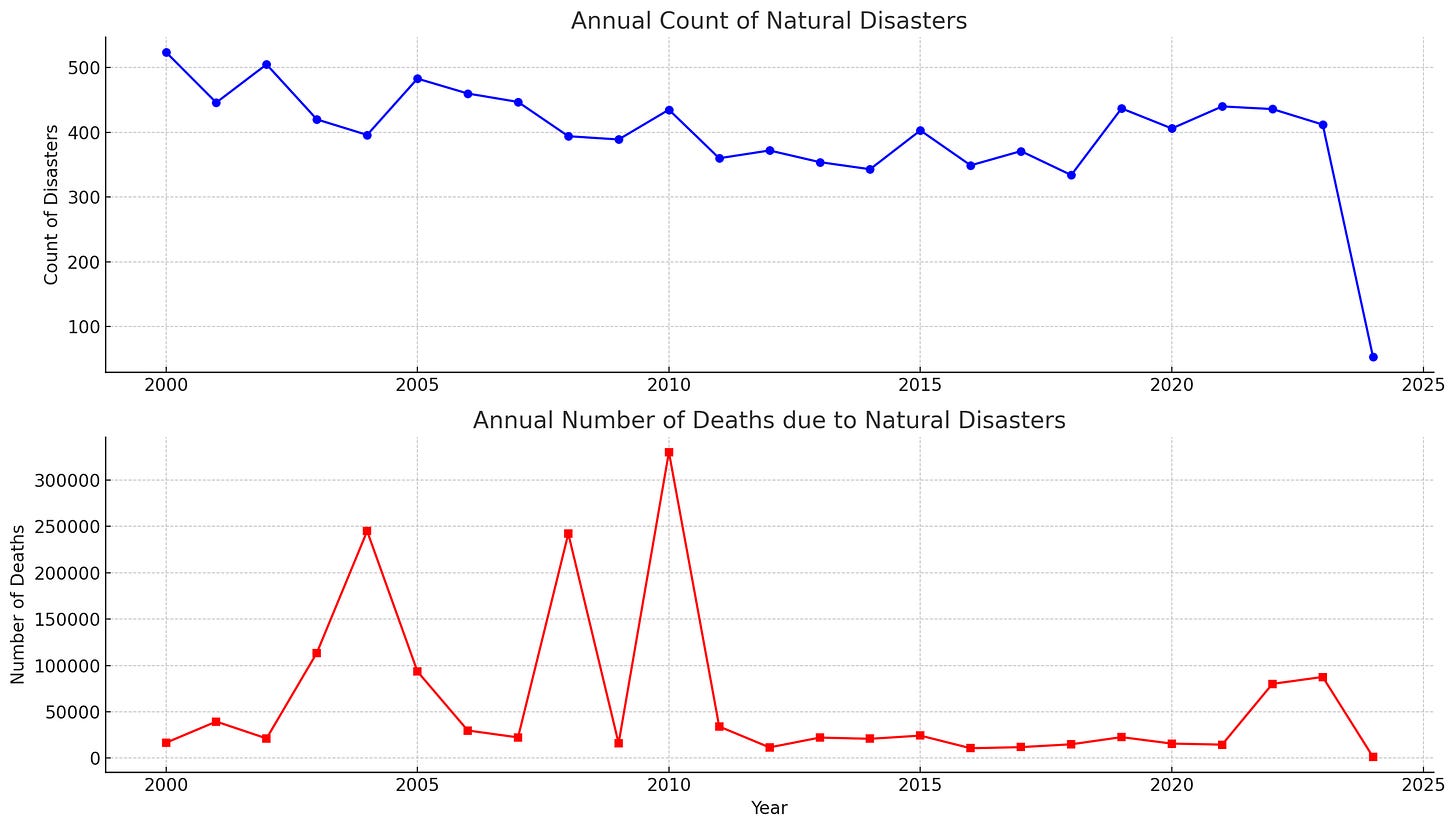

Despite all of this, we do demonstrably live in extremely safe times. If you look at the EM-DAT data, which is a treasure trove by the way, the trend is flat to down. (The last year’s data is partial, that’s why the steep dip down).

But if we do live in the safest of times then whence the worry?

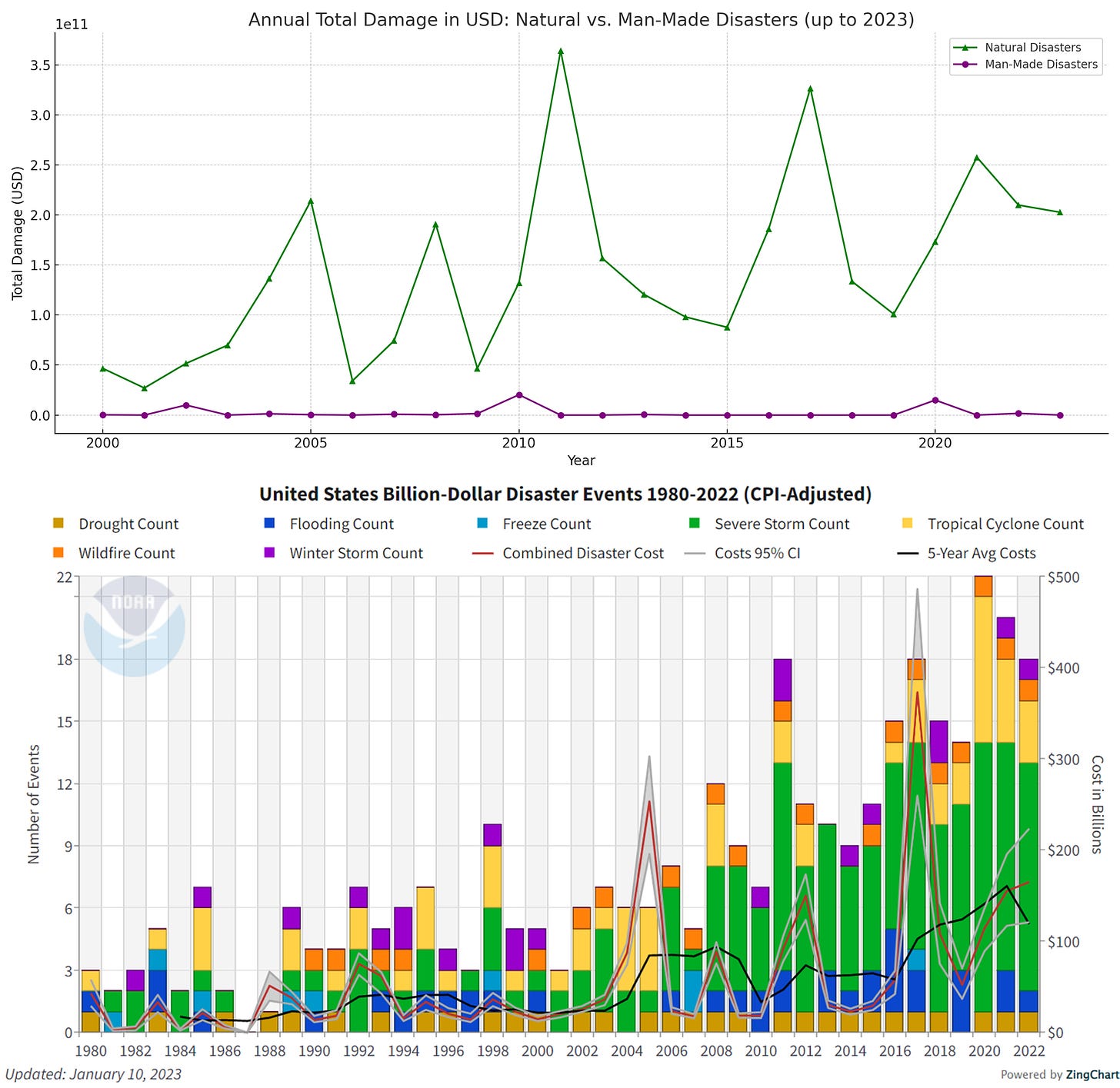

One answer is that it might not feel like its the safest of times because at the same time, natural disasters are increasing in frequency and impact. So maybe people are just replacing one type of disaster for another implicitly in their mental model, and getting scared?

These are also highly expensive disasters, which definitely helps them get publicity, and distorts what we actually think about them?

But that can’t be all of it, surely. We do know how to distinguish between floods happening in India against a ship destroying a bridge in Baltimore. While the former makes us feel insignificant maybe in the eyes of god, it’s not the same as feeling like you’re living on the sufferance of terrorists and a wrong flip of a switch somewhere from disaster.

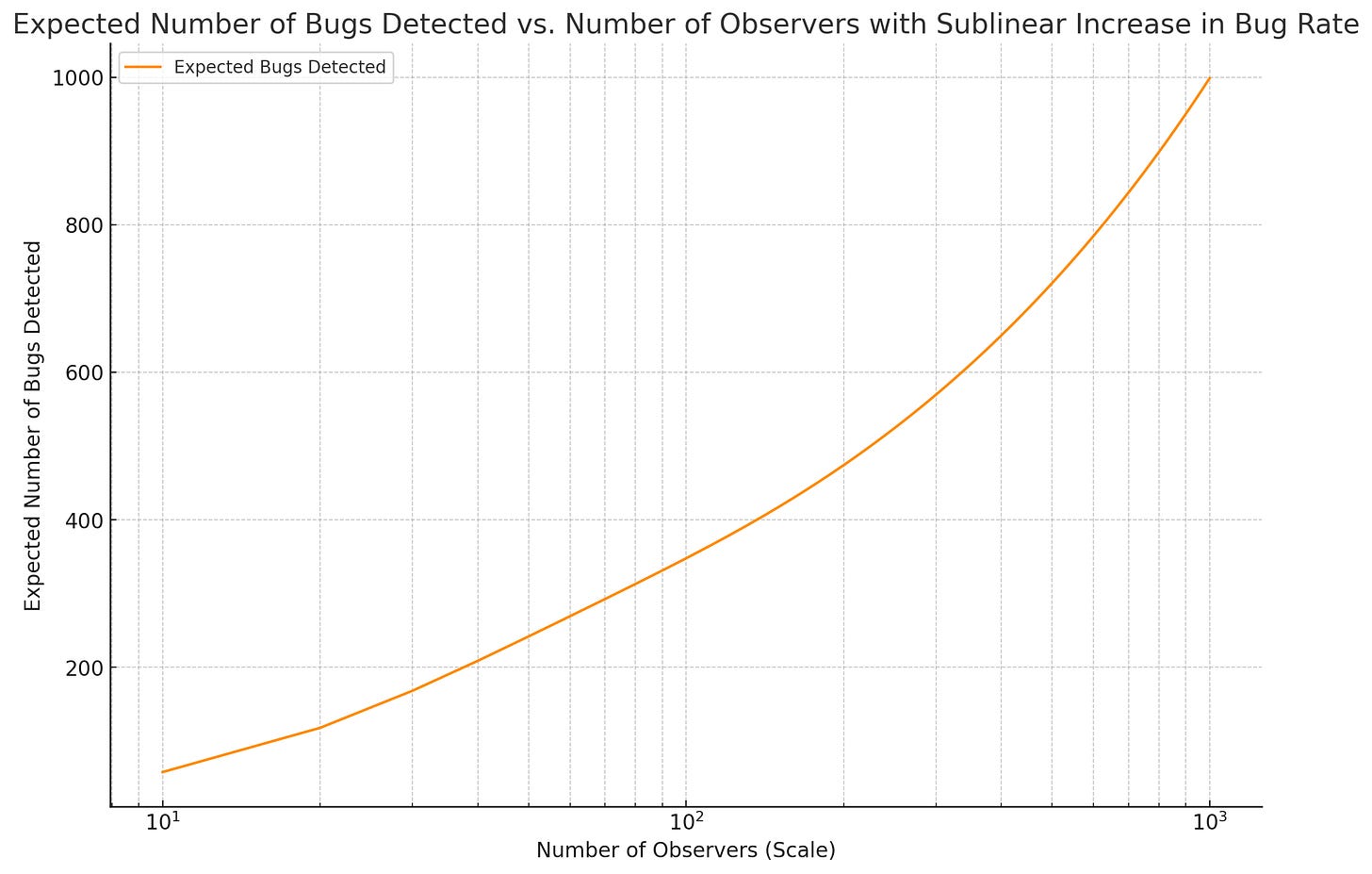

Going a tad academic for a minute, if you live amidst systems which have a large number of eyes on it, then you end up making serendipity your friend. Hence the saying “many eyes make shallow bugs”. It’s not because the bugs themselves are shallow, but because if there is a large enough surface area, then someone somewhere ends up seeing something that doesn’t make sense.

A big reason we don’t see wayward ship’s captains ramming their ships against bridges and piers, is that to become a ship’s captain is not an easy road, and if you were to take it with malicious intentions the already slim chances of success become even slimmer. Not to mention the fact that you will probably get spotted and held back by your peers and subordinates, which makes chance of eventual success even smaller. Thus the equilibrium holds.

Which also means you should expect to see, just from the law of large numbers, a lot of supposedly unlikely ways in which villains are foiled and catastrophes stopped.

It could just be, for instance, that there actually are more Stanislavs around. Vasili Arkhiphov, who commanded the Soviet submarine, also disagreed with the orders to launch a nuclear torpedo. This was during the Cuban missile crisis, famously rather volatile days.

Or in the cyberattack world, an 22 year old anonymous security researcher tweeting as @malwaretechblog and Darien Huss from Proofpoint prevented the WannaCry ransomware attack by accidentally activating a kill switch in its code by registering a particular domain name.

They're not isolated heroes. Heroism seems an option available to many, if not most, as situations unfold..

We are extremely uncomfortable with these equilibria in reality, because it feels like living on the edge. Somehow, maybe because they’re so easily available in movies and entertainment, where disasters loom large and we have someone at fault, we think the world is a cacophony of superintelligent villains or hyper competent terrorists all aiming to disrupt our lives.

But maybe living on the edge is fine. It’s what made up make up pagan gods when civilisation was much younger, why should we be immune to it?

And how do we defeat them? Not through superintelligent heroes, or highly nested supersmart plans, but the pure application of large quantities of self interest, a large number of overlapping plates which filter out the poison. It’s like nature, where the ecology of our wetlands, with overlapping layers of vegetation and microbial life, filter out pollutants from water. Or our immune system. Or the literal overlapping plates that creates high degrees of strength and resilience, from armadillos to fish to bird feathers to pine cones.

A large, complex, interlinked surface which, paradoxically, makes each individual catch seem capricious, as if we are living under Damocles’ sword. “Many eyes make all bugs shallow”.

Serendipitous vigilance is what keeps the wolves at bay, it seems like magic because we don’t see all the other almost-misses, the other hundreds of ways in which it could have also been caught.

Scale brings with it its own benefits. Almost like evolution, with a large number of parallel attempts, many individually unlikely things become likely, and together they form an impenetrable barrier. We underestimate what people can achieve every time we are so surprised at a successful, seemingly prescient action. Individual agency is not unique nor is it so rare that we should be so shocked when it manifests.

(At this point if I know my audience they would like a small mathematical model to look at this, so I made one. If you have n observers, p as the probability of any observer detecting a single bug, and r as the rate at which bugs are introduced into a system, the probability of at least one observer detecting the bug is (1 - (1 - p)^n). If there are a hundred bugs that will get introduced to a system, and you have a 5% chance of finding a bug randomly or through serendipity, just having 1000 observers is the key to finding 100. At 10 observers it’s closer to 40. Even in a worse scenario, if you think the rate of bug introduction increases as a sublinear function of n, then you still get a staggering increase in ability to detect bugs at scale.)

Even recent phenomena like the rise of crypto (where everything has to be cryptographically verified) or the rise in pressure to regulate (everything from financial services to EPA to FDA to AI), the worry about the possible bad actions of a bad actor is what motivates much of public discourse around these topics.

We have built entire trillion dollar economies out of whole cloth by enabling trust at scale, with verify as a remedy rather than a requirement, and yet ‘trust’ by itself is hard to get people to trust in.

The way to solve this isn’t to just have a single silver bullet to create trust, but to have a large number of shots on goal to make even the unlikely of a higher statistical likelihood.

The lesson, and there are many, is that to create a resilient system or an organisation or a movement or a culture or a way of living, is not an act of creating that perfectly thought out solution that is able to thwart all problems, but one of creating scale where there was none, to bring more slices of intellect to bear on the problem, even obliquely, so that you can weaponise serendipity.

Reading about the Baltimore bridge disaster, I found myself very comforted to learn how quickly the sailors and bridge workers responded to stop traffic and keep the disaster from being even worse. I do think the world is mostly peopled by “Petrovs” — and that’s why we can live in this precarious sugar castle with only *occasional* disasters. ¯\_(ツ)_/¯

There are major issues with the "billion dollar disaster" graph. See Roger Pielke analyses on The Honest Broker. In brief, damage is more expensive because we are wealthier. The physical impact (including on lives lost) is quite different.