What would a world with AGI look like?

“Within a decade, it’s conceivable that 60-80% of all jobs could be lost, with most of them not being replaced.”

AI CEOs are extremely fond of making statements like this. And because they make these statements we are forced to take them at face value, and then try to figure out what the implications are.

Now historically the arguments about comparative advantage that Noah Smith has talked about have played out across every sector and technological transition. AI CEOs and proponents though say this time is different.

They’re also putting money where their mouth is. OpenAI just launched the Stargate Project.

The Stargate Project is a new company which intends to invest $500 billion over the next four years building new AI infrastructure for OpenAI in the United States. We will begin deploying $100 billion immediately.

It’s a clear look at the fact that we will be investing untold amounts of money, Manhattan Project or Apollo mission level money, to make this future come about.

But if we want to get ready for this world as a society we’d also have to get a better projection of what the world could look like. There are plenty of unknowns, including the pace of progress and the breakthroughs we could expect, which is why this conversation often involves extreme hypotheticals like “full unemployment” or “building Dyson spheres” or “millions of Nobel prize winners in a datacenter”.

However, I wanted to try and ground it. So, here are a few of the things we do know concretely about AI and its resource usage.

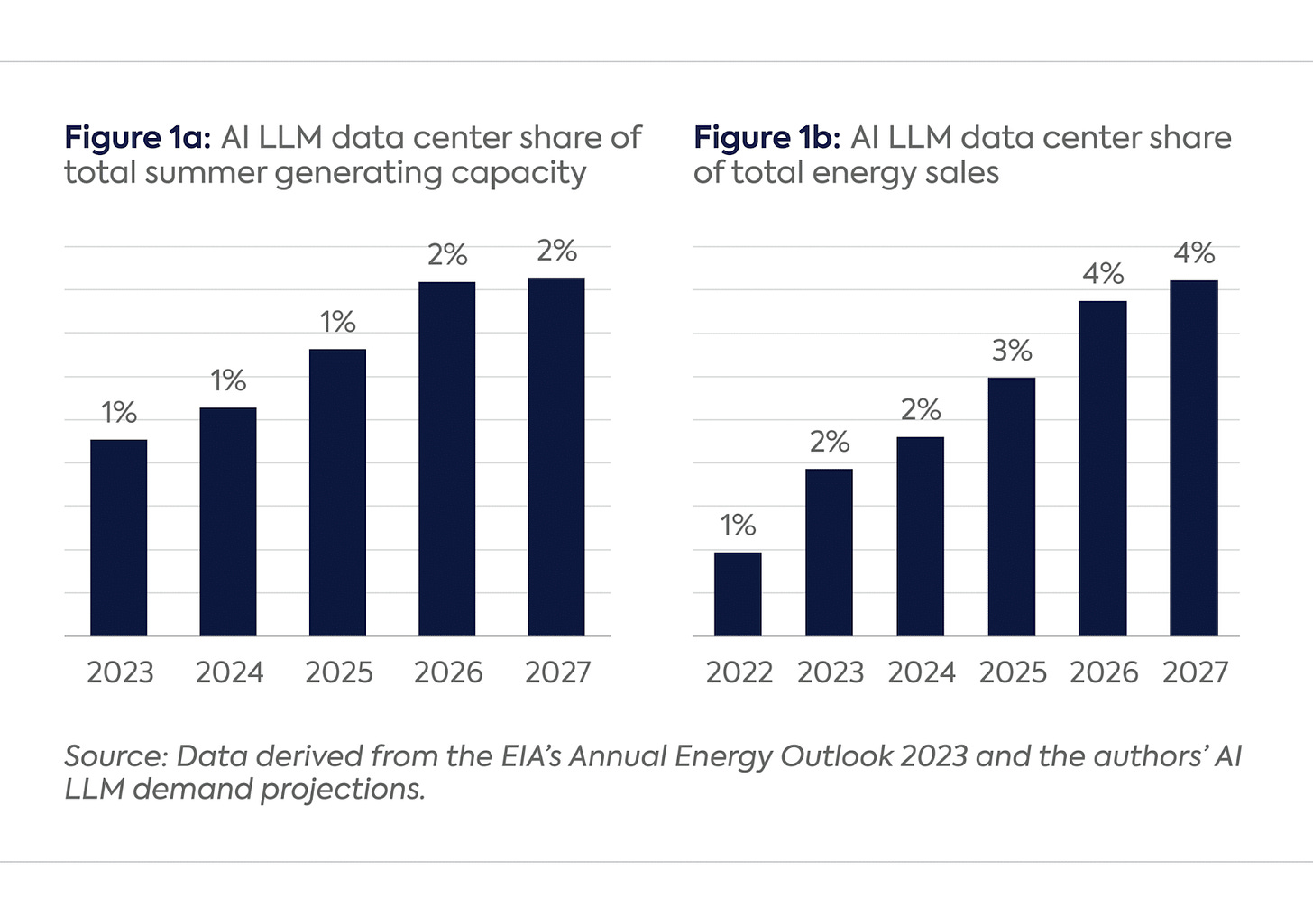

Data centers will use about 12% of US electricity consumption by 2030, fuelled by the AI wave

Critical power to support data centers’ most important components—including graphics processing unit (GPU) and central processing unit (CPU) servers, storage systems, cooling, and networking switches—is expected to nearly double between 2023 and 2026 to reach 96 gigawatts (GW) globally by 2026; and AI operations alone could potentially consume over 40% of that power

AI model training capabilities are projected to increase dramatically, reaching 2e29 FLOP by 2030, according to Epoch. But they also add “Data movement bottlenecks limit LLM scaling beyond 2e28 FLOP, with a "latency wall" at 2e31 FLOP. We may hit these in ~3 years.”

An H100 GPU takes around 500W average power consumption (higher for SXM, lower for PCIe). By the way, GPUs for AI ran at 400 watts until 2022, while 2023 state-of-the-art GPUs for gen AI run at 700 watts, and 2024 next-generation chips are expected to run at 1,200 watts.

The actual service life of H100 GPUs in datacenters is relatively short, ranging from 1-3 years when running at high utilization rates of 60-70%. At Meta's usage rates, these GPUs show an annualized failure rate of approximately 9%.

OpenAI is losing money on o1-pro models via its $2400/ year subscription, while o1-preview costs $15 per million input tokens and $60 per million output and reasoning tokens. So the breakeven point is around 3.6 million tokens (if input:output in 1:8 ratio), which would take c.100 hours at 2 mins per response and 1000 tokens per generation.

The o3 model costs around $2000-$3000 per task at high compute mode. For ARC benchmark, it used, for 100 tasks, 33 million tokens in low-compute (1.3 mins) and 5.7 billion in high-compute mode (13 mins). Each reasoning chain generates approximately 55,000 tokens.

Inference costs seem to be dropping by 10x every year.

If one query is farmed out to, say, 64 H100s simultaneously (common for big LLM inference), you pay 64 × ($3–$9/hour) = $192–$576 per hour just for those GPUs.

If the query’s total compute time is in the realm of ~4–5 GPU-hours (e.g. 5 minutes on 64 GPUs → ~5.3 GPU-hours), that alone could cost a few thousand dollars for one inference—particularly if you’re paying on-demand cloud rates. (Update: I meant *even 5 minutes on 64 GPUs, not *e.g., so this was meant to indicate highly complex inferences)1.

To do a task now people use about 20-30 Claude Sonnet calls, over 10-15 minutes, intervening if needed to fix them, using 2-3m tokens. The alternate is for a decent programmer to take 30-45 minutes.

Devin, the software engineer you can hire, costs $500 per month. It takes about 2 hours to create a testing suite for an internal codebase, or 4 hours to automatically create data visualisations of benchmarks. This can be considered an extremely cheap but also very bad version of an AGI, since it fails often, but let’s assume this can get to “good enough” coverage.

We can now make some assumptions about this new world of AGI, to see what the resource requirements would be like.

For instance, as we’re moving towards the world of autonomous agents, a major change is likely to be that they could be used for long range planning, to be used as “employees”, instead of just “tools”.

Right now an o3 running a query can take up to $3k and 13 minutes. For a 5‐minute run on 64 H100s, that’s roughly .3 total GPU‐hours, which can cost a few thousand dollars. This lines up with the reported $2 000–$3 000 figure for that big‐compute pass2.

But Devin, the $500/mo software engineer, can do some tasks in 2–4 hours (e.g. creating test suites, data visualisations, etc.). Over a month, that’s ~160 working hours, effectively $3–$4 per hour. It, unfortunately, isn’t good enough yet, but might be once we get o3 or o5. This is 1000x cheaper than o3 today, roughly the order of magnitude it would get cheaper if the trends hold for the next few years.

Now we need to see how large an AGI needs to be. Because of the cost and scaling curves, let’s assume that we manage to create an AGI that works on one H100 or equivalent costing 500W each, which roughly costs around half as much as Devin. And it has an operating lifetime of a couple years.

If the assumptions hold, we can look at how much electricity we will have and then back-solve for how many GPUs could run concurrently and how many AGI “employees” that is.

Now, by 2030 data centers could use 12% of US electricity. The US consumes about 4000 TWH/year of electricity. If AI consumes 40% of that figure, that’s 192 TWh/year. Running an H100 continuously will take about 4.38 MWh/year.

So this means we can run about 44 million concurrent H100 GPUs. Realistically, if power and overheating etc exists that means maybe about half of this is a more practical figure.

If we think about the global figure, this will double - so around 76 million maximum concurrent GPUs and 40 million realistic AGI agents working night and day.

We get the same figure also from the 96GW of critical power which is meant to hit data centers worldwide by 2026.

Now we might get there differently, we'd build larger reasoning agents, we'd distill their thinking and create better base models, and repeat.

After all if the major lack is the ability to understand and follow complex reasoning steps, then the more of such reasoning we can generate the better things would be.

To get there we’ll need around 33 million GPUs at the start, at a life of around 1-3 years, which is basically the entire global possible production. Nvidia aimed to make around 1.5-2 million units a year, so it would need to be stepped up.

At large scale, HPC setups choke on more mundane constraints too (network fabric bandwidth, memory capacity, or HPC cluster utilisation). Some centers note that the cost of high-bandwidth memory packages is spiking, and these constraints may be just as gating as GPU supply.

Also, a modern leading‐edge fab (like TSMC’s 5 nm/4 nm) can run ~30 000 wafer‐starts per month. Each wafer: 300 mm diameter, yields maybe ~60 good H100‐class dies (die size ~800 mm², factoring in yield). That’s about 21 million GPUs a year.

The entire semiconductor industry, energy industry and AI industry would basically have to rewire and become a much (much!) larger component of the world economy.

The labour pool in the US is 168 million people. The labour participation rate is 63%, and has around 11 million jobs by 2030 in any case. And since the AGI here doesn't sleep or eat, that triples the working hours. This is equivalent to doubling the workforce, and probably doubling the productivity and IQ too.

(Yes many jobs need physical manifestations and capabilities but I assume an AGI can operate/ teleoperate a machine or a robot if needed.)

Now what happens if we relax the assumptions a bit? The biggest one is that we get another research breakthrough and we don't need a GPU to run an AGI, they'll get that efficient. This might be true but it's hard to model beyond “increase all numbers proportionally”, and there's plenty of people who assume that.

The others are more intriguing. What happens if AGI doesn't mean true AGI, but more like the OpenAI definition that it can do 90% of a humans tasks? Or what if it's best at maths and science but only those, and you have to run it for a long time? And especially what if the much vaunted “agents” don't happen, in the way that they can solve complex tasks equally well, e.g , “if you drop them in a Goldman Sachs trading room or in a jungle in Congo and work through whatever problem it needs to”, but are far more specialist?

What if the AGI can't be perfect replacements for humans?

If the AIs can't be perfect replacements but still need us for course correcting their work, giving feedback etc, then the bottleneck very much remains the people and their decision making. This means the shape of future growth would look a lot like (extremely successful) productivity tools. You'd get unemployment and a lot more economic activity, but it would likely look like a good boom time for the economy.

The critical part is whether this means we discover new areas to work on. Considering the conditions you'd have to imagine yes! That possibility of “jobs we can’t yet imagine” is a common perspective in labor economics (Autor, Acemoglu, etc.) but they've historically been right.

But there's a twist. What if the step from “does 60% well” to “does 90% well” just requires the collection of a few 100k examples of how a task is done? This is highly likely, in my opinion, for a whole host of tasks. And what that would mean is that most jobs, or many jobs, would have explicit data gathering as part of its process.

I could imagine a job where you do certain tasks enough that they're teachable to an AI, collect data with sufficient fidelity, adjust their chains of thought, adjust the environment within which they learn, and continually test and adjust the edge cases where they fail. A constant work → eval → adjust loop.

The jobs would have an expiry date, in other words, or at least a “continuous innovation or discovering edge cases” agenda. They would still have to get paid pretty highly, for most or many of them, also because of Baumol effects, but on balance would look a lot more like QA for everything.

What if the AGI isn't General

We could spend vastly more to get superhuman breakthroughs in a few questions than just generally getting 40 million new workers. This could be dramatically more useful, even assuming a small hit-rate and a much larger energy expenditure.

Even assuming it takes 1000x effort in some domains and at 1% success rate, that's still 400 breakthroughs. Are they all going to be “Attention Is All You Need” level, or “Riemann Hypothesis” level or “General Relativity” level? Doubtful. See how rare those are considering the years and the number of geniuses who work on those problems.

But even a few of that caliber is inevitable and extraordinary. They would kickstart entire new industries. They'd help with scientific breakthroughs. Write extraordinarily impactful and cited papers that changes industries.

I would bet this increases scientific productivity the most, a fight against the stagnation in terms of breakthrough papers and against the rising gerontocracy that plagues science.

Interestingly enough they'd also be the least directly monetisable. Just see how we monetise PhDs. Once there's a clear view of value then sure, like PhDs going into AI training now or into finance before, but as a rule this doesn't hold.

AGI without agency

Yes. It's quite possible that we get AI, even agentic AI, that can't autonomously fulfil entire tasks end to end like a fully general purpose human, but still can do this within more bounded domains.

Whether that's mathematics or coding or biology or materials, we could get superhuman scientists rather than a fully automated lab. This comes closer to the previous scenario, where new industries and research areas arise, instead of “here's an agent that can do anything from book complex travel itineraries to spearhead a multi-year investigation into cancer. This gets us a few superintelligences, or many more general intelligences, and we'd have to decide what's most useful considering the cost.

But this also would mean that capital is the scarce resource, and humans become like orchestrators of the jobs themselves. How much of the economy should get subsumed into silicon and energy would have to be globally understood and that'll be the key bottleneck.

I think of this as a mix and match a la carte menu. You might get some superhuman thought to make scientific breakthroughs, some general purpose agents to do diverse tasks and automate those, some specialists with human in the loop, in whatever combination best serves the economy.

Which means we have a few ways in which the types of AI might progress and the types of constraints that would end up affecting what the overall economy looked like. I got o1-pro to write this up.

Regardless of the exact path it seems plausible that there will be a reshuffling of the economy as AI gets more infused into the economy. In some ways our economy looks very similar to that of a few decades ago, but in others it's also dramatically different in small and large ways which makes it incomparable.

I made a mistake with the math in the next point mixing GPU-hours and GPUs so removed the next bullet point.

While this is true, if an LLM burns thousands of dollars of compute for a single “task,” it’s only appealing if it’s either extremely fast, extremely high‐quality, or you need the task done concurrently at massive scale.

This is a great start, especially considering that most of us are frozen by uncertainty looking at scenarios that could go in such wildly different directions.

Having said that, does this analysis take the exponentials involved seriously enough? For the sake of argument, if inference costs continue to go down 10X per year, does that imply that our assumptions about GPUs / energy will be 4-5 orders of magnitude off by 2030? Will o1-pro level inference cost $2 per year instead of $2000?

I usually shy away from such extreme exponential forecasts, but this seems like a situation where they might apply, especially because all the AI companies are going to be using the best models internally for AI development and training data creation.

Things could get much weirder.

Your math seems incorrect and has a very large error. You quote $192-$576 for 64 GPU-hours and then state the query takes 5.3 GPU hours and will cost $1000. Would it not cost 5.3/64x ($192-$576) which is $16-$48?