I

We live in a culture that's fully saturated by mentions of entrepreneurs. It was said in 2016. Also in 2017. Again in 2018. And ad nauseum including in 2020. And so on and on. So say we all. It's never been easier to start a company. There's just an unprecedented amount of innovation in the world, happening at ever faster pace.

So why aren't we seeing more startups? That's another thread that seems to get a ton of press. There's a decline of entrepreneurship and innovation. Entrepreneurship is not popular. Tyler Cowen has highlighted this trend too as part of his great stagnation thesis, and saw how we're much less likely to switch jobs or move around to find good work.

So which is it? Are we in a golden age of unprecedented and ever-faster innovation, or just mellowing in our golden years?

The data that NBER has put together seems to suggest that larger firms are unambiguously accounting for a greater economic activity share and new firms are not being created faster. This paper argues that the answer is mainly one of demographics. If population is getting older, as it indeed is, and we believe entrepreneurship is unequally represented amongst younger cohorts, the growth rates have to decline.

For instance, let's assume that population is strictly divided into 3 parts - young ones, potential entrepreneurs, and old ones. If over time the distribution spreads to get thicker around the old ones, then the number of potential entrepreneurs will decrease rather monotonically. And that's problem 1.

Problem 2 is that in the absence of new companies being started, the average age of companies stay flat or increase (mostly), since the overall economic pie is still growing. Or at the very least there will be a bifurcation where some will grow a lot and some will stay static or see some declines. This phenomenon results in larger companies ending up becoming larger (feel free to model a bit of endogenous size advantage if you like).

What if the exit rates went up a lot also? Well the ones remaining, if anything, would end up being more concentrated and larger.

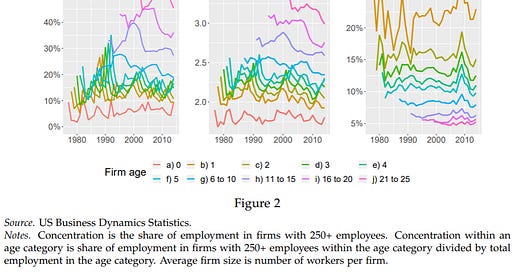

If you do the modelling properly, as the paper shows, it looks something like this.

Either way this is not exactly a resounding success for the entrepreneurship story. Alex Tabarrok also had a paper that asked if entrepreneurship is in decline, and after concluding yes it was, concluded that this probably was an aberrant time period and things will change now that the whole world has mobile phones and digital startups don't recognise borders.

So if the number of firms aren't going up, and there's some decent reasons why, then what explains the gold rush in pretty much every major city around the world for entrepreneurs? It feels like every government has rolled out the red carpet for startups with tax incentives and innovation investment funds and the occasional overpriced artisanal breweries.

Maybe the actual number doesn't matter because most of these companies measured in large scale studies above are small businesses, like a corner-shop selling baked goods and car parts, or bicycle shops and handmade cakes if you're in Brooklyn. What matters is the Googles of the world that grow into modern giants. The VC backed unicorns in other words.

The world is awash in venture capital dollars too. This should be an argument in favour of there being more entrepreneurship and consequently innovation. Part of the answer is that all that glut of money is going towards chasing the few companies that do break through the size and sexiness barrier, which creates a winner's boon like no other.

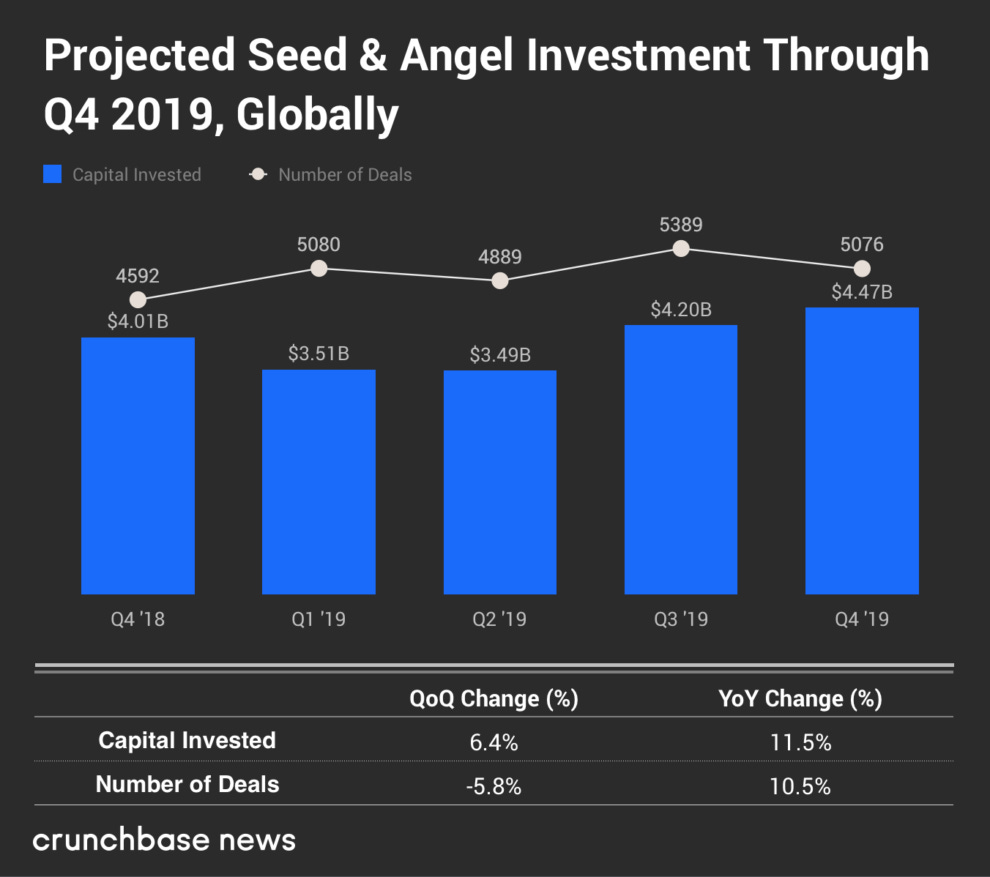

But maybe we should start a bit earlier. Since starting companies is the pain point, this should show up in the earliest stages of investment, right?

Right.

Steady state in the number of deals done, bigger increases in size of deals. Seen over a longer period of time this might even seem inexorable. Even in the earlier stages it seems like there's a winner's boon playing out.

(Parenthetically it also bears out an anecdotal observation that as the venture world has gotten bigger, more industrialised, and dare I say scaled, a larger part of success has also become imitative in terms of deal selection and investment appetite. We look at what's been done and try fund others similar to that in the hope of lightning striking twice.)

But the question here isn't just on why VCs are hunting winners rather than spreading their deals. The answer there is way too prosaic and easy to explain. That's where the money is.

Looking at the success rates of VC backed companies we find that US VC backed startups in 2019 represented 2.27m employees, along with >50% of all global venture funding. To quote NVCA:

In 2019, U.S. venture-backed startups represented approximately 2.27 million employees. The 10,430 high-growth startups that raised capital last year to build and grow their companies hailed from all 50 states and the District of Columbia, 242 Metropolitan Statistical Areas (MSAs), and 397 Congressional Districts. Total capital invested in the U.S. last year reached $133 billion and buoyed global total venture capital investment to $257 billion.

A Stanford GSB analysis also finds the following:

As of December 2013, our sample of public companies had 4,063 firms with total market capitalization of $21.3 trillion. Of those, 710, or 18%, of the companies are VC-backed. Their total market capitalization is $4.3 trillion (20%). These companies tend to be young and fast growing, which explains why their revenue is a relatively smaller fraction of the revenue of the total sample (10%), but their research and development is 42% of the total. That is more than a quarter of the total government, academic, and private U.S. R&D spending of $454 billion. They also employ 4 million people.

But even that analysis finds that VC funding is not a driver of success as much as an indicator, and voices that in what's essentially a giant caveat:

We overstate the importance of VC funding to the extent that successful VC-backed companies may well have been successful even without VC financing.

...

VC-style financing is not the sole reason these companies succeeded. In fact, VC was not even the sole source of financing for many of these companies. However, large and growing fractions of entrepreneurs are choosing VC financing.

So if entrepreneurship overall is declining, while this specific form of entrepreneurship is staying steady and maybe increasing in a decade-long scale, maybe it's not just that there's not enough entrepreneurial activity happening overall. It's that a small but substantially meaningful fraction of the activity is somehow moving into the VC-backed, and ergo potentially more impactful, part of the startup economy.

And if we believe that private company success is what is essential for entrepreneurship to succeed, and it's not a bad metric to choose, then this should make you cheer.

It also tells you that when you look for evidence of things like startup dynamism to measure progress and innovation, averages lie, especially seen without counterfactuals. Sadly the world doesn't stand still for us to do some half-decent social science.

Unfortunately it still doesn't answer the question of why the number of deals isn't spiking more. After all, the known wisdom is that starting a company is phenomenally easy today. Don't just take it from me, Xero thinks so. So does Marc Andreessen, and he ought to know. He argues:

Open-source software and cloud services have made the core infrastructure of technology companies easier and cheaper to build than ever before. The internet has collected and distributed a growing body of practice for the practical know-how of how to build and scale companies.

So if it's so much easier and it's so much cheaper, then even a non-declining straight-ish line should make you wonder. Why aren't there a hell of a lot more companies out there? Why isn’t this the top trending topic on VC Twitter?

II

A secondary concern is whether the analysis thus far overstates the role of startups in the first place. After all, even if only in recent years, some of the biggest innovations have come from larger companies.

Most of the frameworks for AI development have come from the largesse of Google, Facebook and its ilk. Arguably Starlink, which aims to link the whole world up through satellite based internet, came out of an existing SpaceX business. AWS, boosting an entire generation of startups and changing the way all companies and governments do business, came out of an online retailer with well-deserved delusions of grandeur. DeepMind has made some truly remarkable discoveries while shielded from anything resembling responsibility under the giant Google money umbrella.

But in any case, a possible hypothesis is that larger companies are actually seeing all this awesome innovation inside their walls. Let's have a look. One would think that part of the answer of why we're not seeing more startup activity despite the tools of starting a company getting easier and easier is that people are taking advantage of the tools, but are just using them inside their employers.

Unfortunately there seems to be no decent measurement of intrapreneurial activity within companies. A meta analysis concluded as much, that this one measure's a little hard to crack. Which isn't much of a surprise if you've seen large companies operate, but I found it still to be a bit of a bummer.

One idea from McKinsey is to look at aggregate metrics like R&D and disaggregated items like how a new product is contributing to margin as a way to assess this. One issue with this is of course that it's not hard to spend money on R&D without getting much in return, which might make you think you're innovative.

And looking for margins early on can kill any fledgling innovation too. Ask literally anyone who's worked in a 'corporate innovation' gig. It's an output metric, but can only be looked at when outputs are ready to be assessed, and it's hard to know when that might be. If you doubt that too, I'd invite you to take a look at a few of the highest flying cloud software companies and see how profitable they are today. All of which together means that while the metrics are probably right, they're not very implementable.

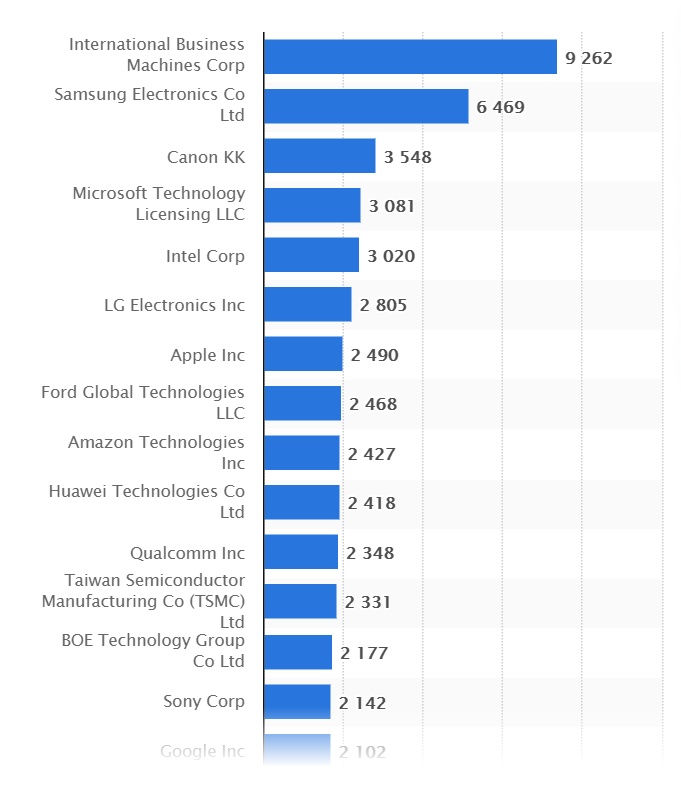

Another way maybe is to look at patents granted. After all that's kind of a sensible way to measure innovation, or at least ongoing innovation trends, right?

Right. We're not in the 70s, which means that when IBM is topping a chart, you should look at it and update your Bayesian priors to make yourself a little more skeptical of the underlying measurement system.

I should probably also mention that IBM has been winning this particular race for the 26th year in a row.

And what does a quarter century of winning get you? Not much by the looks of it. Not even in the longest of terms does their innovation seem to benefit them.

Another hypothesis on why we’re not seeing the impact is that the companies might not be doing patent filings because they could give away secrets. So companies are resorting to trademarks instead. But unfortunately an OECD study also showed that the evidence suggests patents and trademarks are normally complements and not substitutes.

Companies headquartered in the United-States, France, Switzerland, Denmark, Finland, Germany, Japan and the Netherlands jointly use the two intellectual property rights at levels that are above the overall sample average, at both the USPTO and the EPO/OHIM.

There are exceptions, but they are China and Korea, so while it's interesting, the observation is also not completely contrary to what you'd expect in the Western world.

Despite all this, there's clear indication that a lot of innovation is happening within the R&D departments of these larger companies. It might not be flowing through to any actual employees who would've taken it and built a business around it. So maybe that's the part of the chain that seems to be broken.

As a supporting narrative around the technically competent but business foolish giant enterprise, this fits the archetypal story of silicon valley innovation. After all it's the largesse of Xerox that apparently we should all be thanking for the advent of decent computing. And IBM too. Never forget that we should thank them for the emergence of Microsoft.

(as an anecdote, the startups that I've been involved with thus far have had several patents filed between them too, mostly I feel to showcase innovation to their customers and to us, the investors. This has rarely mattered. And if you ask anyone except the CTO, who's extremely keen on it, it has negligible impact on actual business outcomes. In fact one of the major diligence efforts I've undertaken has been to explicitly figure out if a competitor's patent was completely inapplicable, which casts the enterprise into rather dull light.)

The other alternative explanation is that patents are mostly worthless and not a great measure of innovation at all. But that way lies anarchy and the need to demolish basically the structure of how we think about IP, so perhaps it's a topic best left for another essay, since a couple thousand words seem insufficient to the task.

The conclusion that I've reached here is not particularly steadfast - my epistemic status hasn't shifted nearly enough on the topic. I still think large companies have large enough R&D labs, especially in technology related fields, where smart people get left alone enough that they build cool stuff.

I also believe it's almost impossible for those very companies to bring much, if any, of the things they made to the market successfully or profitably. What we have in practice are outsourced R&D labs, from the society's point of view, which folks outside look at and learn from.

And occasionally some smart alecs take an idea from there and build a company around it. The short take here at least has been that there is no such thing as an intrapreneur, since there seems to be no evidence of this mythical creature. Like the yeti, much is rumoured yet not enough has been seen.

It seems though that the word intrapreneur has at least caught on, whether it has resulted in reality or no. It's got its adherents from Google (20% rule and the famous X, though now a tad infamous), Richard Branson (the group of 200 Virgin companies), even Sony with the Playstation.

Whether this is a trend if harder to tell. There are always anecdotes of innovation coming from large companies. The difficulty is to keep them coming. And while sometimes you get the post-it note from 3M, sometimes you also get Instagram Reels.

Put this together with the first question of why we’re not seeing enough entrepreneurship, and the answer does tend to show that perhaps what we’re lacking are enough of those ‘smart alecs’ above who are capable of doing said repurposing. Surely not everyone has transformed into an office drone, which can only mean that the steady rate belies the ease with which we’re meant to be able to start companies today.

If things are truly that easy, and innovation lies around for the plucking with every single one of IBM’s 1000s of patents, then the twitterati are right. What we need is more people like Steve Jobs. Not to remake the iPod or the Mac, but to steal the GUI from Xerox at the right time.