Let’s start with a story.

Robert Owen was a Welsh industrialist. Born in Newtown, Owen moved to Manchester when he was quite young, and quickly rose to prominence as a manager in the cotton industry.

He was self-educated, reading everything that he could get his hands on. He was particularly impressed by the enlightenment thinkers, from Locke’s theories on human development and the importance of education to Rousseau’s ideas on natural human goodness and the corrupting influence of society. They resonated with Owen’s belief in the perfectibility of human beings through environmental improvements.

His success at New Lanark Mills in Scotland, where he implemented progressive labor practices such as fair wages, reasonable working hours, and comprehensive education for workers' children, demonstrated his commitment to improving social conditions through rational management.

After he had his economic success he wanted to put his grand theories into play and create a true utopian society.

So he created New Harmony, in Indiana, aimed at demonstrating the feasibility of social reform through cooperative living and education. He brought about the smartest people he could find, artists and scientists and intellectuals, to make New Harmony incredible.

It worked for a while too, even though its story ends in decline. New Harmony faced economic difficulties, internal disagreements, and lack of enough practical skills among its members.

There are at least a couple interesting things here. One is the fact that New Harmony seemed to have a strong undercurrent around things we consider highly modern, around equality and collective living and education.

The second, which is arguably more interesting, is that they clearly believed in the perfectibility of man. Some combination of the christian belief with the American belief with the Enlightenment belief combined to say “we can be so much better”. They truly believed that with individual effort we could create a better society. And what's more, they felt they could demonstrate it, and did just that by gathering up followers and heading to the middle of America to show the world.

Robert Owens was by no means the only one.

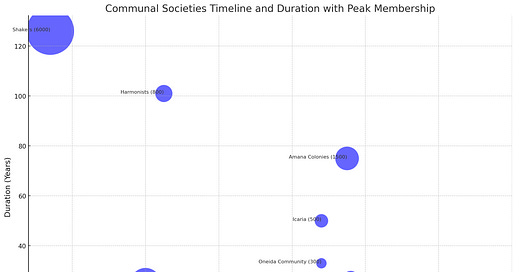

Etienne Cabet wrote a novel called Voyage en Icarie. The novel was about his vision of utopian communism. Later, he led a group of followers from France to establish this utopian community. Since it was about communism, naturally they ended up in Texas.

They later ended up moving because of ‘harsh conditions’ to Nauvoo Illinois, and then later again to Iowa. After this Biblical voyage there was a bit of a leadership kerfuffle, where Cabet was kicked out of his own community. And then, despite all odds, it went on to survive for another fifty years.

If this all sounds rather eccentric, it was. It was considered even so in his days.

John Humphrey Noyes created the Oneida Community in New York. In much more normal cult-like fashion, they practiced “complex marriage”, where every man was considered married to every woman. There was only collective unity. There even was “stirpiculture”, a form of selective breeding to lead to better children.

If this all sounds incredibly crazy and unsustainable, you’d be wrong. They actually survived too, thrived even, because they were creating high-quality silverware to continue their stirpiculturalist communist utopian ways, and that became quite popular!

In 1826, Robert Owen, again, of New Harmony infamy, embarked on another utopian experiment in Orbiston, near Glasgow, Scotland. Partnering with industrialists Abram Combe and Alexander Campbell, Owen aimed to create a cooperative community similar to New Harmony. Orbiston emphasized shared ownership and collective labor, with a strong focus on social and educational reforms.

However, much like New Harmony, Orbiston too struggled with economic viability. The community was plagued by internal conflicts and disagreements among its leaders, which, coupled with financial difficulties, led to its dissolution by 1828. He was better at dreaming about utopia and working towards it than succeeding.

What was it about the 19th century that we had such utopian ideals?

Plato wrote about his utopian ideals in The Republic. Thomas More wrote utopia in 1516. Voltaire wrote Candide in 1759.

The first one was perhaps the Ephrata Cloister, which was a monastery combined with a utopian view of life. Johann Conrad Beissel, German Pietist leader from the late 1600s, founded a utopian community called Ephrata Cloister in 1732, in Pennsylvania.

Born in Eberbach, Beissel was marked by mystical experiences and visions. This reinforced his belief in the need for a strict, ascetic lifestyle dedicated to spiritual purity. So, seeking religious freedom, Beissel immigrated to Pennsylvania in 1720. Soon though he wanted greater solitude and a more rigorous spiritual practice. He wanted to build a perfect religious society, one that also embodied utopian ideals in its vision of a self-sustaining and self-contained group with high morals. A model of Christian piety and communal living.

So he founded the Ephrata Cloister, with around 80 followers. They adopted a monastic lifestyle, worked in farming and papermaking and carpentry, and spent their time preparing for their anticipated heavenly existence. They created beautiful calligraphy, lovely a capella music, and even had a printing establishment! It became famous for its self-sufficiency, producing food, clothing, and creating religious texts.

What was the magic in the 1800s, that many somehow internalised the belief that a few people could come together and figure out the perfect society? Enough that day convinced their followers to move across the known world to try and build something from scratch. An entire economic ideology, political ideology, way of life.

This is the type of ambition that we don't see anymore. Even the undercurrent of the possibility of the belief is clouded in questions about feasibility and desirability and minimum viable product. In skeptical questions and rational inquiry that nevertheless stubs out the little flames of spirit.

Why is that? Why is it that there was a time in our history not so long ago when smart intelligent people legitimately thought that they had the ability to recreate paradise, and then moved heaven and earth to make it so.

This doesn't seem to happen anymore. Our culture is not suffused by people thinking they can make humans better, or that they can create a utopian society. We seem stuck in incrementalist thinking, or sometimes believing in technology to help save us when we’re not busy blaming technology for having created a world that we need saving from.

Samuel Butler wrote Erewhon in 1872, and H G Wells wrote A Modern Utopia in 1905. And a few decades on, all manner of mentions of utopia seems to have vanished from public discourse. It’s a puzzle.

The intellectual climate

One answer is that the intellectual climate was unique then. The enlightenment ideals came about recently, the ideas were spreading through the world. There were books and pamphlets and a cultural move towards building the kinds of utopia that the broad thinkers envisioned. John Stuart Mill wrote the Principles of Political Economy. Tocqueville wrote Democracy in America. And Locke and Rousseu’s influence were still felt.

This was an idea very much of its time, that we could be better by thinking carefully and living better.

However was also the time Marx wrote Das Kapital, in 1867, and the Communist Manifesto two decades before that. It was a time of heavy intellectual debate. And like all times of heavy intellectual debate and confusion, people felt out for all sorts of new ideas and tested them out. And just like all those times of experimentation, it was likely to end in failure.

After all Walden was written in 1854.

Not to mention the fact that part of the ideas did get operationalised in the form of Communist regimes, which didn’t work all that well. And other parts of it got operationalised through bit-and-pieces legislation, in terms of work towards equality of the sexes and better working conditions. Lincoln, after all, was a product of this time. Maybe this reduced the need for such a separate movement?

The economic climate

The economic climate was frothy with progress too, with the industrial revolution having just gotten under way and the output starting to increase wonderfully after millennia of stagnation.

This also meant, perhaps for the first time, the growing pie needed to be redistributed and that became a rather important consideration in society. Which also meant that many more people started looking closely at what we today would call the means of production and tried to figure out whether this newfangled way of life was indeed worth it.

This meant that there were bigger industrialists and the very idea of making tremendous progress through human effort started being seen as mainstream.

It’s the birth of agency.

There’s definitely something to this idea. Individuals definitely seem to have started to matter more? Not just in the scientific or philosophical sense, but in the sense that they could start doing things that would meaningfully change the world.

Technology made it obsolete

Until we had the ability to reshape the world around us through technology, the promise of reshaping the world around us had to deal with social technologies. Which means that even though the optimism of industrial revolution managed to kick-start the interest in creating utopias, the actual practical matter of bringing it about got subsumed by the technologies and scientific advancements that were being made.

Could we believe in this? Possibly, there is definitely some truth to this. But it cannot be the full explanation.

The amount of push back that technology itself got was not small. After all, Luddites came to power around this time, in 1811. Anton Howes has written wonderfully about the birth of the industrial revolution and how it was a gradual process rather than a step change, and while many of the social ills that the utopians wanted to abolish did get solved through technology, many more like the equality of sexes or new economic theories did not. We had to want to do better first.

The frontiers are gone

A large number of the utopian communities were in the United States. The United States in the 1800s was very much still in its wild frontier days, a place where those started hard and sound of mind could go and build a great life.

It's probably not a coincidence that the golden age of Victorian explorers also happened at the same time. The sense of man taming nature, of going to the frontier and finding a new way of life, this was forefront in people’s minds. You can sense it when reading their books, or novels, or newspapers. Dickens wrote in that time, so did Jane Austen. John Stuart Mill too. Not just in the Anglosphere, it was the time of Victor Hugo and Tolstoy and Dostoyevsky and Melville.

When the frontiers existed, we could test ourselves against it. Which meant we could look at the vast expanse and see infinite potential. We only really have it today in the vast reaches of space or maybe the oceans, but it all feels all too jaded. Without more lands to conquer, we’ve succumbed to the melancholy of the human condition.

The intellectual environment and the economic climate and the political climate, none of which were particularly stable, somehow coalesced in the 1800s and pushed a large number of idealists and religious leaders and hard-nosed realists to make their own versions of utopia a reality.

We've lost this. Utopia is a laughingstock today, utopian a pejorative.

Perhaps it’s just the failures of large-scale social engineering, like communism. We tried it. Didn't work! Or the emergence of postmodern skepticism. Starting with Nietzsche in the late 19th century, to Foucault and Derrida, they discussed the flaws with Enlightenment rationalism. It fundamentally questioned grand narratives and universal solutions, thinking them overly simplistic and naive, extending to the Enlightenment idea of progress.

Instead of grand narratives the focus became on micro narratives, skepticism of rational progress, and, perhaps consequently, a reliance on technology to be the answer.

What I find amazing about the utopian societies though is the sheer scale of ambition. They all had their flaws, but they had a philosophical heft that we don't see much. We sometimes make fun of the beliefs of silicon valley entrepreneurs pitching their fruit squeezing startups as changing the world, but here there were literal pastors creating communities to, quite literally, create the utopian world and better the human condition.

They collected members and created the world they thought should exist. Regardless of the success or failure, this is to be admired. Even envied.

What is the modern version of this? We do think about technological advancements that actually solve our problems. Correctly so. And demonstrably we have gotten much better at social considerations. But it's also true that our lives are atomised, many profess the feeling of living inside a hamster wheel, even if the wheel is highly comfortable, and many more seem to talk about bringing forth the Resurgence of a non-economic degrowth agenda.

Crypto arguably tried to have utopian ideals, and so far failed pretty miserably. But its contributions, even with the early-ish examples like Zuzalu, is not yet at the scale nor ambition of New Harmony. Effective Altruism looked to be similar for a minute there too, but that doesn't seem to have lasted either.

We live in a time now that seems all too close to the 1800s in some ways.

The economic climate seems poised for a new epoch, technological changes are making lives unrecognisable, certainly to our parents and also to our children, the very idea of art is changing, new frontiers are being discovered, there is even a rising movement of people dissatisfied with the atomisation of society and what they would call “capitalism” and searching for alternate sources of meaning. We should be able to bring back the idea that life can be better, of working together to bring forth a utopian existence.

The spirit of pioneering ambition is perhaps our best features as a species. We only seem to get it in glimpses as you glance through history, seemingly at random as if a capricious muse bestows it on us, outside our control. But this isn’t preordained, nor is it true. If audacious optimism and a focus on utopian outcomes is achievable, then not doing so is a fault of the spirit. It is worth asking why this form of optimism is no longer around.

A utopian experiment that succeeded will not be recognized as utopian, for instance the Society of Friends, or formerly other names such as the Friends of the Inner Light of Truth, better known as Quakers. Few among them know how much of today's world came from the Quakers. E.g.: Barclays, Lloyds, Cadbury, most of the iron for the early industrial revolution, railroads, cast steel, fixed-price shops, the American-style nuclear family, Pennsylvania, Bryn Mawr , Haverford, Swarthmore, Johns Hopkins, Cornell, Dalton's atomic theory of chemistry, Young's proof of the wave theory of light, etc. etc. (But Quakers have nothing to do with the oatmeal brand, nor any historical link to the Amish.)

Formerly an endogamous group from the mid-1600s to around 1900, I estimate there were fewer than half a million silent-meeting Quakers in the US and Britain in history, with about 50,000 or so today, of whom only a very small fraction have long Quaker ancestry, as my family does. Virtually all of them now are converts (“convinced” Friends, rather than “birthright”); the sect had just about died out when the Quakers' automatic exemption from the the Vietnam War draft attracted a huge influx of Boomers. Today the silent-meeting Quakers are ultra-liberal clubs, defined mostly by extreme political correctness. It's ironic, because the Quakers were patient zero of the Progressive pandemic in the 19th century, but have been repeatedly reinfected by mutated strains of the woke mind virus.

I think the decline decline came from dropping endogamy and lowering membership requirements. That is also the problem for any future utopian experiment -- community, utopian or otherwise, is impossible without the ability to ward off incompatible types of people.

I spent the summer of '88, aged 16, as a part-time cowherd in the tiny, remote Quaker colony of Monteverde, in the Costa Rican Cloud forest. Utopia is possible.

I think the two main reasons to be skeptical that utopias are possible now are:

1) Lots of people have tried and failed, and those failures are recent enough to be documented (with your post here an example of that documentation)

2) Governments are bigger, more capable, and more willing and able to limit technologically mediated change that could help create a utopia

Per 2, I can create a utopia - we need to legalize gengineering somewhere, and let market forces act so that people can pay to have much smarter, healthier, happier, and more attractive kids. When parents can choose the level of neuroticism (low), IQ (high), conscientiousness (high), etc their kids will have, those kids will be able to create better and more utopian societies together than their parents, and provided gengineering capabilities keep increasing, that can be a virtuous spiral.

But gengineering isn't legal anywhere. And it likely won't be legal anywhere for a good amount of time, and if it were legal somewhere, odds are enough people in other countries would agitate about it and try to make it illegal, via soft or hard power. Crabs in a bucket.

Similarly, if you let people sort themselves by things other than wealth and income. Take the people in the top decile of combined IQ, capability, conscientiousness, and mental health and let them form their own society and government. They'll get closer than anyone else to creating a better and more utopian society over time - but wait, we can't do that. There's no process to do it, it's called "secession" and it's a dirty word to all governments everywhere. That top decile pays a lot of taxes, after all. Also, it's probably not diverse or inclusive enough, so they'll all get cancelled or embargoed by trade partners or whatever, and this is also why we can't have tracking by ability in schools in the US.

Back in 18th-19th century times, the federal government was much weaker. Local governments were much weaker. You had a credible means to create a mini society that followed different rules, both legally and socially. You can't do any of that now.

If we did have some means to make more federated enclaves of different legal schemes, then we could have the requisite sorting by ability and inclination, and sorting by technologically-allowed-and-mediated change like gengineering, to actually try to do something different and better. But good luck convincing current governments to give up the cream of their current tax-paying crop and let them go form weird Prospera-like enclaves and have super-babies together.