Why do big businesses seemingly suck at innovation?

A preliminary examination of poor decision making by businesses everywhere!

I

One of the questions that's bugged me forever is why large companies take seemingly obviously uninspired decisions or delay taking seemingly smart ones. Whether it’s Kodak or Xerox or Blockbuster on the one side of missing entire industries, or Microsoft or Google or Blackberry missing their own industry evolutions, the annals are replete with examples.

It's not just companies of course. The experience of the last year has brought out the insanity that most of our leading light institutions have been visibly sub-par while individuals, often unqualified, working with scraps of data, outperform them. And so I was intrigued to try and figure out why is it that the larger institutions are so gullible.

So, time for a story.

In the early 1980s McKinsey gave advice to AT&T that the year 2000 mobile phone industry would have a market of 0.9m devices. Turned out it was closer to 100m. Oops. AT&T lost a bundle, had to sell their business, and then everyone moved on.

Tren Griffin gives a wonderful account of this death here, with an account of why the advice had a particularly nasty toll:

In 1993 AT&T was forced to pay Craig McCaw and his brothers billions of dollars due to the botched estimate. And they gave the cellular business to the spin-offs that were the seven RBOCS.

There's a certain line of argument that uses this fact as an example of why consultants are dumb and useless and don't understand anything about business.

But there are two other facts that complicate the picture. One, consulting firms (notoriously) hire only the smartest people they can find, and any group of folks from them is like an absurd business overachievers team. One of my teams had a top trauma surgeon, a brigadier general and an Olympian (none of those were me). Short of a business zoo these people don't usually show up together. Dumb they're not.

The second is that the public perception is that they fleece the clients with generic advice. This one has a bit more leg. But still, McKinsey, Bain and BCG together make around $25 Billion in revenues, and an absurd fraction of that in profits, mostly with 85-90% returning clients. They must get something for continually spending that money! If everyone everywhere is getting fleeced after paying a few grand a day per consultant, these firms should be falling apart at the seams to begin with.

But the billion dollar question remains. What, if anything, is wrong with this picture? How can the smartest business people, when they work together, and when they get paid millions, make such egregious mistakes?

II

One reason often cited is executive buy-in for projects they've already decided they want to do.

And that does happen. It happens subtly, like when you get "strong hypotheses" from your client, or you have internal discussions on what ideas the client might not be predisposed to. What I've seen though is that they serve less as direct buy-in routes, since who today looks at a consultant's report and goes "ah yes, if they say so" anyway. But it does serve as a way for executives to de-risk their decisions. The execs have figured out kind of what they need to do, in a vague outline sort of fashion, and are interested in getting some justification that gives them some sense of whether their intuition is okay, and also if the others in the organisation agree.

But consultants traditionally do try to start from a position of genuine analysis and try to craft their story accordingly. Even assuming they're not, you'd think that an industry built on blatant pandering could only last a decade or two at the most, not a century.

When I was first recruited, they told me that I'd be working on the most important problems at the biggest companies. And they were mostly right. The biggest reason that consultants are hired though is because when something complicated needs to be done at any large company, which is almost everything by the way, then someone needs to help explain what needs to be done to everyone else.

And to provide such clarification and business reasoning you do need a solution that makes logical sense, but will also be bullet proof at a later date when someone inevitably asks "why did you do that?"

Clarification turns out to be a non-trivial skill.

What the above means is that consultants try to make decisions that are legible (understandable to everyone, within their own context), and defensible (one that's highly internally coherent, and if there's any fault it's not in the logic but rather some extrinsic dataset).

And that's really where consulting shines. It creates a clear storyline that is both data backed and internally coherent that management can use to do things. Not necessarily evil or stupid or premeditated things. Just regular normal business things that otherwise would've been shrouded in confusion.

Complexity taming is thus a big part of the value proposition.

Knowing that, how could McKinsey ever give the conclusion to AT&T that everything they knew and stood for would basically go up in smoke in a couple decades? Even if they wanted to, they would never be able to put that in a report.

Because someone would ask them how they know. And they won't have an answer. They can have extrapolations and maybe hunches from other industries and expert justifications and technical experts talking about Moore's law. But there's no evidence. There's no data point showing that this was the birth of an entire industry. If they had wanted to show that this would happen, the burden of proof is immensely high. You could have gone and asked people, but would they know either? Like the saying goes, "if you ask people what they wanted, they wouldn't say a car. They'd say a faster horse".

So obviously the question gets rephrased and answered with assumptions that would seem sensible because there's tons of data available, but turns out to be completely wrong.

Bear in mind that the reason that Tren gives on the right way to think is from Craig McCaw, who looked at things from first principles and stated the inevitability of mobile phones because:

humans started out as nomadic - it may be our most natural state

Do you see a hardheaded business person using that as their north star for decisions? If anyone other than the CEO said that they'd get fired. If a CEO said that they'd probably get fired too.

McKinsey isn't in the job of getting things right. They're in the job of getting things to be coherent. And to be coherent is to have a worldview that an idea and a proposed course of action align with.

The thing is, that's not a bad strategy. New industries don't pop up that often. In nearly a century of life, think about how few stories like the AT&T one have actually surfaced. Would they rather get the 95% of mundane stuff they're asked to do correct, like a tech transformation of a bank or market sizing for cars in China? Or do they go out on a limb and actually try to answer the AT&T question and try to guess the size of an industry that didn't exist yet in anyone's conception of the future?

This isn't a job where getting the hard questions right helps McKinsey. They don't get paid for being right. They're not Private Equity where they get the cellphone industry right, and because the industry is worth $100Bn they get a cut of that from ownership.

No, in fact the beauty of the model is that they get paid the same whether the advice is bullshit or genius. People think this is nuts, because ownership confers massive profits. The consultants say this makes the advice impartial. And they're right, it does. Trying to get one crazy prediction correct out of a hundred because that's enough to get you all the money in the world is a completely different business. A way more fragile business. And because they don't try to take crazy swings hoping one hits, like venture capitalists.

Instead they go the other way. You hire McKinsey to get sensible advice about things that are known and won't change that much. Where their knowledge about the history of an industry and benchmarks from competitors really can actually help.

If that seems fanciful just know that the top companies in the world, whether that's Goldman Sachs or Google, don't really act as clients. Even when they very occasionally do, it's not for their "key" department.

Consultants help the laggards catch up to the rest of the pack, acting as a sort of slow and expensive information diffusion mechanism in the industry. They're like a really expensive efficient markets mechanism at play. They're not in the "here's what Google should do next in search" game. They're in the "here's what Exxon should do to cut its costs 5% while growing in green energy" game. The latter is much easier, much larger and much more frequent.

What's amazing to me is that this shows extremely clearly how subtly incentives guide behaviour. You can have the dumbest outcomes from the smartest people pretty easily. Bear in mind that in the same time we've also seen Microsoft immolate around $20Bn with their missteps in internet and cellphones, and Google not far behind.

If you want an occupation that lasts for a good long while, where the vagaries of the technology world or the business world don't mess you up, then studying this is instructive.

Because they're not paid "success based" they're treated as unbiased. Because their goal is a high hit %, they try to be as measured and conservative in their analyses as possible. Because their job is to get repeat clients, despite huge mental blocks internally about not even mentioning money below the Partner level, client satisfaction is top of mind.

Put all of that together, you have the best example of how you can build a multi billion business out of crafting perfect rationalisations for most businesses. If you tell an executive that you can take their cognitive overhead from complexity away, you'll be rewarded handsomely. Everyone is afraid of complexity, and even if your solutions are only internally coherent rather than externally coherent, it'll still get purchase!

III

But why is the type of complexity wrangling that McKinsey brings valuable to companies anyway?

When the company is smaller you can have a cadre of people whose job it is to understand all the interface points amongst the world and the company, and to manage it all. It's the micromanaging CEO who knows every inch of the product and every customer's favourite lunch.

But as you get larger that job becomes more complicated. There's way more things than any individual can keep in their heads. So you need to go get new heads so they can keep those things in their mind. And then you can keep an abstracted view of their views in your mind.

Since the map is not the territory, your abstracted view of the reality will always have gaps. You can theoretically solve for misses by ensuring rapid feedback from the "front lines", metis, though this too soon gets bogged down in complexity. If you add another 2 layers of abstraction the problem gets exponentially harder.

So you end up trying to streamline the flow of information that reaches you, make it easier to understand, because that way you can stay more on top of things.

Harvard Business Review calls this coherence, and sings its praises:

Sustainable, superior returns accrue to companies that focus on what they do best. The truth is that simple, and yet it’s incredibly hard to internalize. It is the rare company indeed that focuses on “what we do better than anyone” in making every operating decision across every business unit and product line. Rarer still is the company that has aligned its differentiating internal capabilities with the right external market position. We call such companies “coherent.”

Most things in the world of management have to do with managing things internally, or dealing with customers and competitors and the general world externally. The literature likens this to war, and who am I to resist. You're either inside the castles arranging the troops or outside fighting off the invaders. The problem is, some of the things you do, you can tell pretty quickly if you got them right or not. Put a few grain barrels the wrong way around, you get to know fast. Arrange the archers the wrong way, there's a gap that a stray halberd can poke in from.

And some things that the master strategists do, you just have to take on faith that they're right. Put pike men here, put your cavalry here, and archers over there. Will that be the best thing to do? We'll see eventually. Or maybe not even then, because who knows if this was the war that was won by the other team because they had better steel than you, or because the water you fed your horses gave them dysentery.

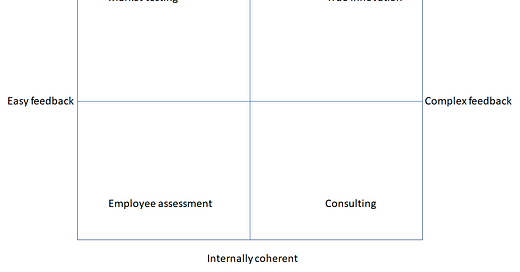

And so to make sense of the world of management you put your actions in two axes. In one, many jobs have as their requirement for something to be made internally coherent vs externally coherent. Internally coherent means that your logic is the lynchpin of any argument, while externally coherent means the congruence with reality is. While it might seem like being aligned with reality is good for everything, that turns out to be not true!

For any number of tasks where it's crucial to ensure everyone's pulling together as a team in the same direction, internal coherence is paramount. If you disbelieve me, try to get something done in an organisation where everyone's deciding for themselves what the most important priorities for the company are. Like every sports movie ever says, "you gotta be one team".

The second axis is whether getting any kind of feedback on a job is easy or complex. Most times if the results of your actions are easily visible or measurable, that goes in the easy pile. If they can't be disentangled easily or needs long time horizons to bear fruit, then that's the complex pile. (There's probably a more elegant formulation possible here.)

With that in mind, I think there's a matrix for decision making that looks something like this.

Internal coherence is an indicator of consistency. It's a way for the external world to predict that when you do X the result will always be Y. When you're managing on the basis of a highly abstracted view of your organisation, predictability is key. And for predictability, which is seen as a virtue, you need internal coherence.

On the right hand side of the matrix above, the map is free is for senior managers and the C-suite to take whatever actions suit their agenda. You feel like buying a few companies will boost your image and get the analysts excited. So you go and do it. By the time you know if you screwed up, enough time has passed, and you can argue for it in any direction.

Microsoft is my favourite here. They bought Skype for $8B, did barely anything with it. They bought Nokia, and skipped the entire mobile revolution. Were these just dumb acquisitions? It's unclear, because they also bought GitHub and LinkedIn and they both seem to be doing okay. The situation is complex enough that there's no easy feedback from the market. All you can do is to call them dumb mistakes in the "Innovation" bucket and move on.

Similarly, wherever easy feedback is available, which is the left side of the matrix, you tend to adjust your approach pretty quickly. As an example from the software world, this is where Product Managers shine. They look at a working product, do user research and interviews, create an idea of small things that can be changed that will increase the [insert key KPI here] by 5%, and make the change.

The cumulative effect of multiple such changes is that the technical debt builds, the build complexity increases, and the usability of the product for a large fraction of the user base suffers. For the paradigmatic example, look at Google. They have done this to every single one of their extraordinarily successful products - Chrome is now a memory hog with basic performance, Gmail is bloated to the point you don't know where to click, GChat became several different chat versions all of which seemed interchangeable, ending up in Hangouts, which is now getting deprecated, Maps had new functionality added to the point that what used to take 2 clicks now takes 7 (from personal test). And so on and on.

And businesses are not alone. We want legibility anywhere decisions get made. In AI one of the bigger fights going on now is around the need for more legibility within the decisions it makes.

We don't want to be judged by black boxes. We want to be judged by black boxes that try to explain themselves. We want to live in a world that is rules ordained and understandable rather than a Kafkaesque nightmare.

This means that we're stuck with legibility creation experts like consultants as long as businesses need to be run as businesses. If you want a zaibatsu where if you want a bank, you own a bank, then the bets are off. But the trend towards increased complexity and decreased degrees of freedom for companies to operate come from its size. As they try to make themselves better understood internally, all arranged in neat rows and columns, there's the inevitable fallout in terms of becoming less useful in facing external circumstances. As they try to grab on to the complex frontiers by systematising it, they lose out even more.

Until we find better ways to be okay with not knowing what's going on, or create better information wrangling mechanisms, businesses will still focus on legibility and internal coherence. Most of them anyway, since on the other hand, we get to enjoy more like this ownership structure of Samsung group.

How they get anything done is beyond me.

If you want to build something you can manage, you need legibility, and you’ll fall prey to the vagaries from part I. If not, you’ll end up stuck in a spiderweb of complexity without finding easy ways out. If you’re small you get the luxury of being nimble. If you’re large, you’re stuck between Scylla and Charybdis. Maybe that's the point.

Fantastic article Rohit.

I worked in consulting for a short period and still didn't understand why they got paid like they did😅.

Interesting perspective. I agree that consultants get to charge huge fees to bring internal coherence rather than to drive new thinking. As they say " they take your watch and tell you the time". But it is the way they do it - slick presentations and models - that enables better understanding that earns them their position.

I have a different view to the AT & T situation which resulted in them making Craig McCaw a rich man and paying $12.6B to get into the cellular business.

1. In 1983, the cellular business was in its early stage startup phase. AT & T focused on what they did best - long distance fixed line communication. They effectively allowed Craig to lead the development of the cellular business in the US which took significant effort and capital.

2. In 1993 - the cellular business was ready to take off. AT & T stepped back into the ring to buy the now established winning business and focused on what they did best - scale the business to its current state.

3. Do note that in 1993 they bought the business for stock - no cash payments were made. Since then this investment has paid back to A T & T shareholders multi-fold. It is possible that AT & T might have driven the cellular business growth as a new product line internally. My assessment is that this would have taken more than a decade and a significantly larger cash investment than the $12.6B.

What if cellular business had died in its infancy and Craig had failed - AT & T would not have lost anything - in fact, we would not be writing about this now!!

Was the decision to focus on what they do best the right strategy for AT & T? Is it not better to allow innovation to happen in the hands of a gritty, no holds barred entrepreneur like Craig that beat the barriers down to create a winner? Did A T & T do well at scaling the infant business and making it a giant winner??