Why isn't there a philosophy of business?

A highly speculative exploration

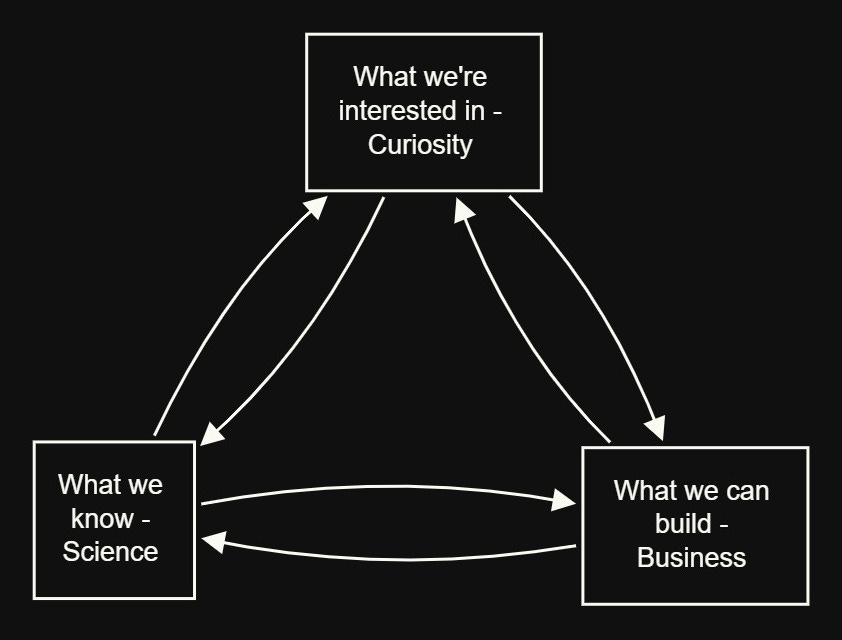

Seems there are two archetypes of techno-optimists. There are science focused people who want to get ever more precise answers to specific questions. And there are business people who want to see what actually works in real life.

Imagine you have an idea you want to explore, and you need to get some funding to go do it. Your options are to get money with the intention of it being an investment that’ll generate a return - either monetary, like venture capital or loans, or non-monetary, like grants.

Venture money, in business, lets you scale your business, to pivot and create such that you make something people want. Grant money, in science, lets you experiment on your hypotheses, to pivot and create such that you can make something people want.

For both the idea isn’t to have a complete thing, but to get to the next stage where you get more funding, once the initial idea is shown to have promise.

For both, there is payoff. For venture capital, the payoff is capital. Eventually if it succeeds it makes enough money that the original investment is net positive. For grants, the payoff is social or cultural, to get known as the patron or the funder of something important, to accumulate social capital much as venture accumulates financial capital.

The second is definitely less fungible and more speculative, since unlike money it isn’t a clear commodity you can accumulate or trade.

But also, the types of hypotheses that are tested are different. Businesses do things to test “do my prospective customers want more of X”, and science often tests “is X a correct explanation of this phenomenon”. It’s efficacy vs accuracy.

The key question in science is, "is it true?" The key question of business is "will it work?"

If science is the work of identifying new niches in the knowledge landscape, business is the work of expanding into and populating that landscape.

The scientific focus leads you to efforts to try and understand, pin down, things you want to know and things you think you know. A lot of the time the focus is on diving deeper into ever-narrower straits, to try and make sure the hypotheses you have aren't false. Whether its Popperian falsification or just elimination of alternatives, science focuses on what qualifies as true.

This is also why you can have a singular inventor in science, but business by definition is a team endeavour, because scale is success.

The business focus leads you to try and see how things can be done. It's not particularly concerned with accuracy per se, as much as efficacy. Ideally the things you do would work in the real world because they're right, but neither your hypothesis nor your approach need be correct for the result to be correct. In other words, you can be wrong about your idea, your approach and your beliefs, and you can still be successful.

Circling these two worlds is the world of curiosity, which in some ways is the ur-ability, the one that guides all effort.

Its interesting though that we have an entire field dedicated to our pursuit of truth and knowledge as its codified philosophy.

Philosophy of science is a sub-field of philosophy concerned with the foundations, methods, and implications of science. The central questions of this study concern what qualifies as science, the reliability of scientific theories, and the ultimate purpose of science. This discipline overlaps with metaphysics, ontology, and epistemology, for example, when it explores the relationship between science and truth. Philosophy of science focuses on metaphysical, epistemic and semantic aspects of science. Ethical issues such as bioethics and scientific misconduct are often considered ethics or science studies rather than philosophy of science.

We’ve had Thomas Kuhn argue how the process actually works, in his seminal book, and argue how science develops by exploiting once you’re within a paradigm, and occasionally exploding out into a new paradigm.

But surely there are major philosophical questions that need to be asked from its companion, business too. Just like the philosophy of science has its examinations and exhortations, shouldn’t there be a parallel field that at least attempts to systematise the theory and practice of business1?

Firms exist because some achievements are so big that they can only be done by a group of people, together.

You have to create a Ship of Theseus out of your collective selves, so it's able to survive the replacement of any part.

Similar trends exist in the philosophy of language (investigates the nature of language and the relations between language, language users, and the world), or the philosophy of education (investigates the nature of education as well as its aims and problems). There’s even a supposed philosophy of space and time. But not something like:

Philosophy of business is a sub-field of philosophy concerned with the foundations, methods, and implications of business. The central questions of this study concern what qualifies as a business, the reliability of business theories, and the ultimate purpose of business.

Just like science is the best way we've found to get an understanding of the world, business feels the best way we've found to make that understanding manifest in the world. We need both to make progress, but one seems quite under theorised.

There’s a long standing argument about why economists aren’t much richer, considering they purport to understand at least some parts of the world better than others. This didn’t always used to be the case - David Ricardo was the richest economist of his time, and Keynes did investing rather well!

But somewhere along the past couple centuries, the distinction between “I know this better than anyone else” and “I can use the knowledge, or an approximation thereof, to do something useful” has diverged substantially! To the point where in Friedman’s department, specialising in monetary economics, folks lost their shirts betting interest rates would fall when they, in fact, rose.

Keynes too made and lost a fortune betting on huge macro moves, helped by his economic insights, and remade a fortune only when he started buying good companies cheaply. In fact, just a few months before he got wiped out, he confidently said.

Money is a funny thing . . . As the fruit of a little extra knowledge and experience of a special kind, it simply (and undeservedly in any absolute sense) comes rolling in.

I wrote about how in the investing world, in the practical financial world, there were no sacred cows; everyone acts on some version of their beliefs, even if only partially accurate. But I highlight a rather contentious exchange here from a great interview.

COWEN: If I look at the macroeconomic literature, it seems to me, even GDP — when we run statistical tests, it’s hard to distinguish that from a random walk with trend. There’s not a lot of obvious mean reversion in the system.

DALIO: I think we’re referring to different things. You’re referring to what you’re reading in the literature, and I’m referring to my 50 years of experience and what I’m doing, so we have a different perspective about those things.

COWEN: Tell me what’s wrong with the literature. Those are actual numbers taken from government databases. You run statistics on them — returns are close to a random walk. GDP is close to a random walk with trend.

DALIO: It’s not random at all. In other words, do you think where interest rates are is random? Do you think it’s random? Do you think that if these things change . . . let’s take that example. Do you think that it would be random that the Federal Reserve would tighten monetary policy? Do you think it’s random that we’re having inflation pressures? Do you think it’s random? Do you think those things are random?

Warren Buffett has said much the same thing time and time again.

The practitioner’s knowledge seems to be happily incomplete, inchoate and often illegible, while producing better results than the more rigorous, complete and predictive theories of the theorists.

But I’ve often felt economists get too much grief here. It’s the same everywhere. Physicists aren’t good at being engineers - physicists are often not great engineers. Biologists, god forbid, aren’t great doctors.

There’s something about highly practical fields which are characterised by trial and error, filling a niche successfully, and often blindly pivoting within the adjacent possible till you get a successful result, which don’t seem all that amenable to theoretical rigour.

The theory here isn’t that rigour isn’t needed, it’s that thinking rigour and practical efficacy don’t necessarily happen at the same time within a field. Monetary policy as theorised lives (it would seem) at least decades ahead of how it is actually practiced. Investing is in the opposite phase where theory is decades behind practice. In the case of something like AI, it’s right on point.

All of these spaces are under theorised. Practical knowledge about things that we do seem to be left in the realm of “try it out and see what works”.

“Philosophy of X” seems to be mostly dedicated to those X which are vague enough to require systematisation, or theoretical enough to be amenable to further theorising.

I find it interesting that the more practical the consideration, the less its scrutinised or theorised. We use rules of thumb and heuristics and vague notions of what makes sense and trial-and-error to somehow muddle through. And while there are a thousand articles about how to build a software business, almost all of them are pretty useless when you try and apply them, because they’re usually idiosyncratic and uncopyable. They are, at best, ladders you throw away after using, like cliches whose meanings you came to understand only after you experienced the thing it refers to.

When worlds outside science and business choose to imitate aspects of it, they pick and choose from these. The philanthropic world has, by and large, focused on the grant based funding mechanisms and the accumulation of social capital in terms of prestige. The world of EA, in slight contrast, has focused on grant giving, but used the evidence based approach that characterises much of science. The case studies are akin to peer reviewed science, and prestige accrued is almost entirely social.

(There are various crypto options that tries to convert this social capital into financial capital, though so far they remain stuck in calculating the exchange rate.)

The reason I think a bit more systematisation here is valuable is precisely because the tools it develops are used far and wide. We saw grant giving become more like venture capital. We see patrons use similar processes of evaluation to fund people. We bemoan increased financialisation in tech and increased studying-to-the-test in science.

Most things that change the world require both. We need science to figure out what’s right and expand the frontier of knowledge, and business to help scale the benefits of things that are so discovered, even though they don’t overlap in every case.

At the very least a study of this would help us have the right toolkit and vocabulary to at least discuss the topic better. Right now we’re inundated with anecdote laden, case study driven, mental model filled HBR pablum, most of which is about as useful as an elevator pitch. Isn’t it time we moved beyond this?

One way to think of this is as mining, looking at science as the way to go out to the frontiers of knowledge and chisel out a new ore. But no matter how precious you find that ore, unless the seam is developed and you productively mine it, bring it back and use it, it remains but a curio.

If the answer is that navigation inside a complex adaptive system requires trial and error, that’s fair. But it would be better if we had ideas on how we could do this better too. Whether it’s thinking of an idea to pursue or figuring out the right way to create an organisation to solve a problem, feels like we could do with some better thinking.

Economics does have a collection of views that starts to answer some of this. I mean, obviously, since it's not purely de novo speculation. The closest we’ve gotten is the Theory of the Firm, which looked at why firms even exist.

It has its start from Coase’s seminal work that says organisations exist because friction and menu costs mean that you can't buy all goods and services you need on the open market.

In simplified terms, the theory of the firm aims to answer these questions:

Existence. Why do firms emerge? Why are not all transactions in the economy mediated over the market?

Boundaries. Why is the boundary between firms and the market located exactly there in relation to size and output variety? Which transactions are performed internally and which are negotiated on the market?

Organization. Why are firms structured in such a specific way, for example as to hierarchy or decentralization? What is the interplay of formal and informal relationships?

Heterogeneity of firm actions/performances. What drives different actions and performances of firms?

Evidence. What tests are there for the respective theories of the firm?

(I do find it interesting that the first question regarding the existence of the firm couch's it in terms of why not a market, rather than the more existential why at all.)

I enjoyed this.

This reminded me of an anecdote about a famous early electrical engineer who had a lot of practical experience who was taking classes at Columbia with a theorist he didn't like. He supposedly used his cutting edge practical knowledge to trick his professor into electrocuting himself in front of the class during demonstrations. Business and academia seem to attract different kinds of people and the former tend to skip grad school or go to industry straight after (see SV becoming a bigger employer of top econ phds).

I can think of some examples of famous modern academic economists who got rich. Hal Varian went from Stanford to Google early on to design their auctions. Julian Simon ran a successful mail-order business and wrote a book about it. He also wrote a paper suggesting that airlines run a reverse auction to handle overbooking, which was rejected by airlines at the time but was widely adopted a decade later. (I don't think he made money from the latter.)

Nobel economist Paul Samuelson got rich as an early investor in Berkshire Hathaway, while promoting a strong version of efficient market theory in public. Buffett would complain that this was hypocritical (without referring to him by name), but he seems to be over it now.

https://www.wsj.com/articles/what-you-can-learn-from-one-of-warren-buffetts-smartest-investors-11545411745

Thanks for this! It helps crystallize some of my thoughts on finances. The financial world is not random, but its trends and effects are so unpredictable it's more productive to treat it as though it is random. Thus, the key skill is an ability to work productively with uncertainty, to ride the waves of uncertainty instead of seeking a rock-solid provable foundation.